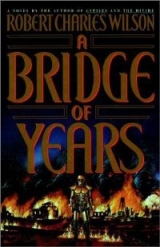

Текст книги "A Bridge of Years"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

A Bridge of Years

by Robert Charles Wilson

Woe is me, woe is me!

The acorn’s not yet fallen from the tree

That’s to grow the wood

That’s to make the cradle

That’s to rock the babe

That’s to grow a man

That’s to lay me to my rest.

—Anonymous, “The Ghost’s Song”

Prologue: April 1979

Soon, the time traveler would face the necessity of his own death.

He had not taken that decision, however, or even begun to contemplate its necessity, on the cool spring morning when Billy Gargullo burst through the kitchen door into the back yard, heavily armed and golden in his armor.

The time traveler—whose name was Ben Collier—had begun the slow, pleasant labor of laying out a garden at the back of the lawn. He had hammered down stakes and marked the borders with binding twine. Next to this patch of grass and weed he had placed a shovel, a rake, and a tilling device called a “garden weasel,” which he had found in a Home Hardware store in the Harbor Mall. Ben was looking forward to the adventure of the garden. He had never gardened before. He understood the fundamentals but wasn’t certain what might thrive in this sunny, damp patch of soil. Therefore he had purchased a random selection of seeds from the hardware store rotary rack, including corn, radishes, sunflowers, and night-blooming aloe. In his right hand he held a packet of morning glories, reserved for a space by the fence, where they’d have something to climb on.

He had lived alone on this property—two acres of uncultivated woodland and a three-bedroom frame house—for fifteen years now. A tiny chunk of time by any reasonable scale, but substantial when you lived it in sequence. He had arrived at this outpost in August of the year 1964 and since then he had not held a conversation more prolonged than the necessary hellos and thank yous directed at store clerks and delivery people. Occasionally someone would move into the house down the road, would climb the long hill to introduce himself, and the time traveler would be friendly in return … but there was something in his manner that discouraged a second visit. He was an ordinary seeming, round-faced, genial young man (not as young as he seemed, of course; quite the contrary) who smiled and wore Levi’s and check shirts and short hair and who, on recollection, would remind you of something superficially pleasant but somehow disturbing: a pool of water in a forest clearing, say, where something old and strange might at any moment rise to the surface.

He had lived alone all this time. For Ben, it was not an especial hardship. He had been chosen for his solitary nature and he possessed hidden resources in advance of contemporary technology: slave mnemonics, tactile memory, a population of tiny cybernetics. He wasn’t lonely. Nevertheless he was, in a very real sense, alone. He was a careful and dedicated custodian; but the serenity of the house and the property occasionally seduced him into lapses of attention. Sometimes he caught himself daydreaming.

Now, for instance. Peering into this deep tangle of weeds, he imagined a garden. Gardening is a kind of time travel, he thought. One invested labor in the expectation of an altered future. Blank soil yielding flowers. A trick of time and water and nitrogen and human hands. These seeds contained their own blooms.

He looked at the package in his hand. Heavenly Blue, it said. The picture was impossibly gaudy, a riot of turquoise and purple Technicolor. As a species, the morning glory had been endangered for years before his birth. He imagined these flowers rising along the old, fragrant cedar planks of the fence (cedar: another casualty). He imagined their blooms in the summer sunlight. He would step out onto the back porch in the last glimmer of a hot, dry day, and there they would be, laced into the wood like bright blue filigree. In the future.

He was gazing at the package—filled with these thoughts—when the marauder burst through the kitchen door.

He had had some warning, subliminal and brief, enough to start him turning toward the house. He felt it as a disturbance among the cybernetics, and then as their sudden silence.

The marauder was dressed in what Ben recognized as military armor of the late twenty-first century, an armor rooted deep into the body, a prosthetic armor tied into the nervous system. The marauder would be very fast, very deadly.

Ben was not without his own augmentation. As soon as the peripheral image registered, emergency auxiliaries began to operate. He ducked into the meager cover of a lilac bush growing at the edge of the lawn, some few feet from the forest. He had time to wish the lilacs were in bloom.

He had time for a number of thoughts. His reflexes were heightened to the inherent limits of nerve and muscle. His awareness was swift and effortless. Events slowed to a crawl.

He looked at the intruder. What he saw was a blur of golden movement, the momentary shadow of a wrist weapon poised and aimed. Ben couldn’t guess what had brought this man here, but his hostility was obvious, the threat unquestionable.

Ben was weaponless. There were weapons hidden in the house, but he would have to pass by the marauder to reach them.

He stood up and dodged left, beginning a zigzag course that would take him to the side of the house and then around to the front, a window or a door there. As he stood, the marauder fired his weapon.

It was a primitive but utterly lethal beam weapon, common for its era. Ben recalled photographs of bodies burned and dismembered beyond recognition, on a battlefield years from here. As he stood, the beam scorched air inches from his head; he imagined he could taste the bright, sour ionization.

Still, the right sort of armor would have protected him. He possessed such an item—in the house.

This was a sustaining thought; but the house was too far, the lawn an unprotected killing ground. He glimpsed the marauder crouching to take aim; he ducked and rolled forward, too late. The beam intersected his left leg and severed it under the knee.

He felt a brief, terrible burst of pain … then numbness as the damaged nerves shut themselves down. Crippled, Ben fetched up against a birch stump projecting from the grass. He had been meaning to pull that stump for years now. The severed portion of his leg—now a barely recognizable tube of flayed meat—rolled past him. Absurdly, he wanted to pull it back to himself. But the leg was gone now—past recovery. He would need a new one.

He felt briefly dizzy as opened arteries clamped themselves shut. The gushing of blood from the blackened wound slowed to a trickle.

Clever programs had been written into the free sequences of his DNA. For Ben, this was not a deadly injury. A grave impediment, however, it most certainly was.

He was helpless here. The birch stump was no cover at all and the marauder was primed for another shot. Ben lurched forward, grinding his bloody knee-end into the dirt, hopped two paces and then rolled again in a drunken tumble that might have succeeded if the marauder had been aiming by line of sight; but the weapon was equipped with a target-recognition device and the beam cut twice across Ben’s body—first severing his right hand at the wrist and then slicing deep into his abdominal cavity. Blood and flame flowered across his shirt, which he had bought at the Sears in the Harbor Mall.

Now Ben began to consider dying.

Probably it was unavoidable. He understood how profoundly damaged he was. He experienced waves of dizziness as major arteries locked or dilated in a futile attempt to maintain blood pressure. Numbness spread upward from his hip to his collarbone: it was like slipping into a warm bath. He lay on the grass where his momentum had carried him, loose-jointed and faint.

He turned his head.

The marauder stood above him.

His armor was quite golden, blinding in the sunlight.

The intruder gazed down at Ben with an expression so absolutely neutral of emotion that it provoked a pulse of surprise. He doesn’t much care that he’s killed me, Ben thought.

The marauder leveled his wrist weapon one more time, now at Ben’s head.

The weapon was unimpressive, built into the curiously insect-jointed machinery of the armor. Ben looked past it. Saw a flicker of a smile.

The marauder fired his weapon.

Most of the time traveler’s head vanished in a steam of bone and tissue.

Billy Gargullo regarded the time traveler’s body with a new and sudden distaste. Here was not an enemy any longer but something to be disposed of. A messy nuisance.

He took the corpse by its good arm and began to drag it into the wooded land behind the house. This was a long, hot process. The air was cool but the sun bore down mercilessly. Billy followed a narrow path some several yards, unnerved by the lushness of this forest. He stopped where the path curved away to the left. To the right there was a clearing; in the clearing was a slatboard woodshed, ivy-choked and abandoned for years.

He probed the door of the shed. One hinge was missing; the door sagged inward at a cockeyed angle. Sunlight played into the damp interior. There were stacks of mildewed newspapers, a few rusty garden tools, a hovering cloud of gnats.

Billy wrestled the time traveler—the lacerated meat of his body—into the sour, earthy shade of the building. His motion caused a tower of newspapers to tumble over the corpse. The papers thumped wetly down and Billy grimaced at the sudden reek of mold.

He stepped back from the door, satisfied. Possibly the body would be found, but this would deter suspicion at least for a while. He wasn’t planning to spend much time here.

He paused with one hand on the sun-hot wall of the shed.

There was a sound behind him, faint but unsettling—a rustle and chatter in the darkness.

Mice, Billy thought.

Rats.

Well, they can have him. He closed the door.

Billy’s first shot had blown the package of morning glory seeds out of the time traveler’s hand.

A stray corner of his beam sliced into the package and scattered its contents across the lawn. The charred paper—the words Heavenly Blue still brownly legible—drifted to earth not far from the birch stump where the time traveler lost his leg. The seeds were dispersed in a wide curve between the stump and the fence.

Most were eaten by birds and insects. A few, moistened by the next night’s rainfall, rooted in the lawn and were choked by crabgrass before the shoots saw light.

Four of them sprouted in the rich soil alongside the cedar fence.

Three survived into the summer. The few blossoms they produced were gaudy by August, but there was no one to see. The grass had grown tall and the house was empty.

It would be empty for a few summers more.

PART ONE – The Door in the Wall

One

It was a modest three-bedroom frame house with its basement dug a little deeper than was customary in this part of the country, pleasant but overgrown with bush and ivy and miles away from town.

It had been empty for years, the real estate agent said, and the property backed onto a cedar swamp. “Frankly, I don’t see a lot of investment potential here.”

Tom Winter disagreed.

Maybe it was his mood, but this property appealed at once. Perversely, he liked it for its bad points: its isolation, lost in this rainy pinewood—its blunt undesirability, like the frank ugliness of a bulldog. He wondered whether, if he lived here, he would come to resemble the house, the way pet owners were said to resemble their pets. He would be plain. Isolated. Maybe, a little wild.

Which was not, Tom supposed, how he looked to Doug Archer, the real estate agent. Archer was wearing his blue Bell Realty jacket, but the neat faded Levi’s and shaggy haircut betrayed his roots. Local family, working class, maybe some colorful relative still logging out in the bush. Raised to look with suspicion on creased trousers, which Tom happened to be wearing. But appearances were deceptive. Tom paused as they approached the blank pine-slab front door. “Didn’t this used to be the Simmons property?”

Archer shook his head. “Close, though. That’s a little ways up the hill. Peggy Simmons still lives up there—she’s nearly eighty.” He raised an eyebrow. “You know Peggy Simmons?”

“I used to deliver groceries up the Post Road . Came by here sometimes. But that was a long while ago.”

“No kidding! Didn’t you say—”

“I’ve been in Seattle for most of twelve years.”

“Any connection with Tony Winter—up at Arbutus Ford?”

“He’s my brother,” Tom said.

“Hey! Well, hell! This changes things.”

In the city, Tom thought, we learn not to smile so generously.

Archer slid the key into the door. “We had a man out here when the property went up for sale. He said it was in fairly nice shape on the inside, but I’d guess, after it’s been closed up for so long—well, you might take that with a grain of salt.”

Translated from realty-speak, Tom thought, that means it’s a hellacious mess.

But the door eased open on hinges that felt freshly oiled, across a swatch of neat beige broadloom.

“I’ll be damned,” Archer said.

Tom stepped over the threshold. He flicked the wall switch and a ceiling light blinked on, but it wasn’t really necessary; a high south-facing window allowed in a good deal of the watery sunshine. The house had been built with the climate in mind: it would not succumb to gloom even in the rain.

On the right, the living room opened into a kitchen. On the left, a hallway connected the bedrooms and the bath.

A stairway led down to the basement.

“I’ll be damned,” Archer repeated. “Maybe I was wrong about this place.”

The room they faced was meticulously clean, the furniture old but spotless. A mechanical mantel clock ticked away (but who had wound it?) under what looked like a Picasso print. Just slightly kitschy, Tom thought, the glass-topped coffee table, the low Danish Modern sofa; very sixties, but immaculately preserved. It might have popped out of a time capsule.

“Well maintained,” he said.

“You bet. Considering it wasn’t maintained at all, far as I know.”

“Who’s the owner?”

“The property came up for state auction a long time ago. Holding company in Seattle bought it but never did anything with it. They’ve been selling off packets of land all through here for the last year or so.” He shook his head. “To be honest, the house was entirely derelict. We had a man out to evaluate these properties, shingles and foundation and so on, but he never said—I mean, we assumed, all these old frame houses out here—” He put his hands in his pockets and frowned. “The utilities weren’t even switched on till late last week.”

How many cold winters, hot summers had this room been closed and locked? Tom paused and slid his finger along a newel post where the stairs ran down into darkness. His finger came away clean. The wood looked oiled. “Phantom maid service?”

Archer didn’t laugh. “Jack Shackley’s the listed agent on this. Maybe he was in to tidy up. Somebody did a phenomenal job, anyway. The listing is house and contents and it looks like you have some nice pieces here—maybe a little dated. Shall we have a look around?”

“I think we should.”

Tom circled twice through the house—once with Archer, once “to get his own impression” while Archer left his business card on the kitchen counter and stepped outside for a smoke. His impression was the same both times. The kitchen cupboards opened frictionlessly to spotless, uniformly vacant interiors. The linen closet was cedar-lined, fragrant and bare. The bedrooms were empty except for the largest, which contained a modest bed, a chest of drawers, and a mirror– dustless. In the basement, high windows peeked out at the rear lawn; these were covered with white roller blinds, which the sun had turned brittle yellow. (Time passes here after all, he thought.)

The building was sound, functional, and clean.

The fundamental question was, did it feel like home?

No. At least, not yet.

But that might change.

Did he want it to feel like home?

But it was a question he couldn’t answer to his own satisfaction. Maybe what he wanted was not so much a house as a cave: a warm, dry place in which to nurse his wounds until they healed—or at least until the pain was bearable.

But the house was genuinely interesting.

He ran his hand idly along a blank basement wall and was startled to feel … what?

The hum of machinery, carried up through gypsum board and concrete block—instantly stilled?

Faint tingle of electricity?

Or nothing at all.

“Tight as a drum.”

This was Archer, back from his sojourn. “You may have found a bargain here, Tom. We can go back to my office if you want to talk about an offer.”

“Why the hell not,” Tom Winter said.

The town of Belltower occupied the inside curve of a pleasant, foggy Pacific bay on the northwestern coast of the United States .

Its primary industries were fishing and logging. A massive pulp mill had been erected south of town during the boom years of the fifties, and on damp days when the wind came blowing up the coast the town was enveloped in the sulfurous, bitter stench of the mill. Today there had been a stiff offshore breeze; the air was clean. Shortly before sunset, when Tom Winter returned to his room at the Seascape Motel, the cloud stack rolled away and the sun picked out highlights on the hills, the town, the curve of the bay.

He bought himself dinner in the High Tide Dining Room and tipped the waitress too much because her smile seemed genuine. He bought a Newsweek in the gift shop and headed back to his second-floor room as night fell.

Amazing, he thought, to be back in this town. Leaving here had been, in Tom’s mind, an act of demolition. He had ridden the bus north to Seattle pretending that everything behind him had been erased from the map. Strange to find the town still here, stores still open for business, boats still anchored at the marina behind the VFW post.

The only thing that’s been demolished is my life.

But that was self-pity, and he scolded himself for it. The quintessential lonely vice. Like masturbation, it was a parody of something best performed in concert with others.

He was aware, too, of a vast store of pain waiting to be acknowledged … but not here in this room with the ugly harbor paintings on the wall, the complimentary postcards in the bureau, pale rings on the wood veneer where generations had abandoned their vending-machine Cokes to sweat in the dry heat. Here, it would be too much.

He padded down the carpeted hallway, bought a Coke so he could add his own white ring to the furniture.

The phone was buzzing when he got back. He picked it up and popped the ring-tab on the soft-drink can.

“Tom,” his brother said.

“Tony. Hi, Tony.”

“You all by yourself?”

“Hell, no,” Tom said. “The party’s just warming up. Can’t you tell?”

“That’s very funny. Are you drinking something?”

“Soda pop, Tony.”

“Because I don’t think you should be sitting there all by yourself. I think that sets a bad pattern. I don’t want you getting sauced again.”

Sauced, Tom thought, amused. His brother was a well-spring of these antique euphemisms. It was Tony who had once described Brigitte Nielsen as “a red-hot tamale.” Barbara had always relished his brother’s bon mots. She used to call it her “visiting Tony yoga”—making conversation with one hand ready to spring up and disguise a grin.

“If I get sauced,” Tom said, “you’ll be the first to know.”

“That’s exactly what I’m afraid of. I called in a lot of favors to get you this job. Naturally, that leaves my ass somewhat exposed.”

“Is that why you phoned?”

A pause, a confession: “No. Loreen suggested—well, we both thought—she’s got a chicken ready to come out of the oven and there’s more than enough to go around, so if you haven’t eaten—”

“I’m sorry. I had a big meal down at the coffee shop. But thank you. And thank Loreen for me.”

Tony’s relief was exquisitely obvious. “Sure you don’t want to drop by?” Brief chatter in the background: “Loreen’s done up a blueberry pie.”

“Tell Loreen I’m sorely tempted but I want to make it an early night.”

“Well, whatever. Anyway, I’ll call you next week.”

“Good. Great.”

“Night, Tom.” A pause. Tony added, “And welcome back.”

Tom put down the phone and turned to confront his own reflection, gazing dumbly out of the bureau mirror. Here was a haggard man with a receding hairline who looked, at this moment, at least a decade older than his thirty years. He’d put on weight since Barbara left and it was beginning to show —a bulge of belly and a softness around his face. But it was the expression that made the image in the mirror seem so ancient. He had seen it on old men riding buses. A frown that announces surrender, the willing embrace of defeat. Options for tonight?

He could stare out the window, into his past; or into this mirror, the future.

The two had intersected here. Here at the crossroads. This rainy old town.

He turned to the window.

Welcome back.

Doug Archer called in the morning to announce that Tom’s offer on the house—most of his carefully hoarded inheritance, tendered in cash—had been accepted. “Possession is immediate. We can have all the paperwork done by the end of the day. A few signatures and she’s all yours.”

“Would it be possible to get the key today?”

“I don’t see any problem with that.”

Tom drove down to the realty office next to the Harbor Mall. Archer escorted him through paperwork at the in-house Notary Public, then took him across the street for lunch. The restaurant was called El Nino—it was new; the location used to be a Kresge’s, if Tom recalled correctly. The decor was nautical but not screamingly kitschy.

Tom ordered the salmon salad sandwich. Archer smiled at the waitress. “Just coffee, Nance.”

She nodded and smiled back.

“You’re not wearing your realty jacket,” Tom said.

“Technically, it’s my day off. Plus, you’re a solid purchase. And what the hell, you’re a hometown boy, I don’t have to impress anybody here.” He settled back in the vinyl booth, lean in his checkerboard shirt, his long hair a little wilder than he had worn it the day before. He thanked the waitress when the coffee arrived. “I looked into the history of the house, by the way. My own curiosity, mainly.”

“Something interesting?”

“Sort of interesting, yeah.”

“Something you didn’t want to tell me until the papers were signed?”

“Nothing that would change your mind, Tom. Just a little bit odd.”

“So? It’s haunted?”

Archer smiled and leaned over his cup. “Not quite. Though that wouldn’t surprise me. The property has a peculiar history. The lot was purchased in 1963 and the house was finished the next year. From 1964 through 1981 it was occupied by a guy named Ben Collier—lived alone, came into town once in a while, no visible means of support but he paid his bills on time. Friendly when you talked to him, but not real friendly. Solitary.”

“He sold the house?”

“Nope. That’s the interesting part. He disappeared around 1980 and the property came up for nonpayment of taxes. Nobody could locate the gentleman. He had no line of credit, no social security number anybody could dig up, no registered birth—his car wasn’t even licensed. If he died, he didn’t leave a corpse.” Archer sipped his coffee. “Real good coffee here, in my opinion. You know they grind the beans in back? Their own blend. Colombian, Costa Rican—”

Tom said, “You’re enjoying this story.”

“Hell, yes! Aren’t you?”

Tom discovered that he was, as a matter of fact. His interest had been piqued. He looked at Archer across the table– frowned and looked more closely. “Oh, shit, I know who you are! You’re the kid who used to pitch stones at cars down along the coast highway!”

“You were a grade behind me. Tony Winter’s little brother.”

“You cracked a windshield on a guy’s Buick. There were editorials in the paper. Juvenile delinquency on the march.”

Archer grinned. “It was an experiment in ballistics.”

“Now you sell haunted houses to unsuspecting city slickers.

“I think ‘haunted’ is kind of melodramatic. But I did hear another odd story about the house. George Bukowski told me this—George is a Highway Patrol cop, owns a double-wide mobile home down by the marina. He said he was up along the Post Road last year, cruising by, when he saw a light in the house—which he knew was unoccupied ’cause he’d been in on the search for Ben Collier. So he stopped for a look. Turned out a couple of teenagers had broken a basement window. They had a storm lantern up in the kitchen and a case of Kokanee and a ghetto blaster—just having a good old party. He took them in and confiscated maybe an eighth-ounce of dope from the oldest boy, Barry Lindell. Sent ’em all home to their parents. Next day George goes back to the house to check out the damage—the kicker is, it turns out there wasn’t any damage. It was like they’d never been there. No matches on the floor, no empties, everything spit-polished.”

Tom said, “The window where they broke in?”

“It wasn’t broken anymore.”

“Bullshit,” Tom said.

Archer held up his hands. “Sure. But George swears on it. Says the window wasn’t even reputtied, he would have recognized that. It wasn’t fixed—it just wasn’t broken.”

The waitress delivered the sandwich. Tom picked it up and took a thoughtful bite. “This is an obsessively tidy ghost we’re talking about.”

“The phantom handyman.”

“I can’t say I’m frightened.”

“I don’t guess you have any reason to be. Still—”

“I’ll keep my eyes open.”

“And let me know how it goes,” Archer said. “I mean, if that’s okay with you.” He slid his business card across the table. “My home number’s on the back.”

“You’re that curious?”

Archer checked out the next table to make sure nobody was listening. “I’m that fucking bored.”

“Yearning for the old days? A sunny afternoon, a rock in your hand, the smell of a wild convertible?”

Archer grinned. The grin said, Hell, yes, I am that kid, and I don’t much mind admitting it.

This man enjoys life, Tom thought.

Heartening to believe that was still possible.

Before he drove out to the house Tom stopped at the Harbor Mall to pick up supplies. At the A P he assembled a week’s worth of staples and a selection of what Barbara used to call bachelor food: frozen entrees, potato chips, cans of Coke in plastic saddles. At the Radio Shack he picked up a plug-in phone, and at Sears he paid $300 for a portable color TV.

Thus equipped for elementary survival, he drove to the house up along the Post Road.

The sun was setting when he arrived. Did the house look haunted? No, Tom thought. The house looked suburban. Cedar siding a little faded, the boxy structure a little lost in these piney woods, but not dangerous. Haunted, if at all, strictly by Mr. Clean. Or perhaps the Tidy Bowl Man.

The key turned smoothly in the lock.

Stepping over the threshold, he had the brief but disquieting sensation that this was after all somebody else’s house … that he had arrived, like Officer Bukowski’s juvenile delinquents, without credentials. Well, to hell with that. He flicked every light switch he could reach until the room was blisteringly bright. He plugged in the refrigerator—it began to hum at once—and dropped the Cokes inside. He plugged in the TV set and tuned the rabbit ears to a Tacoma station, a little fuzzy but watchable. He cranked the volume up. Noise and light.

He preheated the ancient white enamel stove, watching the elements for a time to make sure everything worked. (Everything did.) The black Bakelite knobs were as slick as ebony; his own fingerprints seemed like an insult to their polished surface. He slipped a TV dinner into the oven and closed the door. Welcome home.

A new life, he thought.

That was why he had come here—or at least that was what he’d told his friends. Looking around this clean, illuminated space, it was possible—almost possible—to believe that.

He took the TV dinner into the living room and poked at the tepid fried chicken with a plastic fork while MacNeil (or Lehrer, he had never quite sorted that out) conducted a round-table discussion of this year’s China crisis. When he was finished he tidied away the foil plate into a plastic bag– he wasn’t ready to offend the Hygiene Spirit just yet—and pulled the tab on a Coke. He watched two nature documentaries and a feature history of Mormonism. Then, suddenly, it was late, and when he switched off the set he heard the wind turning the branches of the pines; he was reminded how far he had come from town and what a large slice of loneliness he might have bought himself, here.

He turned up the heat. The weather was still cool, summer still a ways off. He stepped outside and watched the silhouettes of the tall pines against the sky. The sky was bright with stars. You have to come a long way out, Tom thought, to see a sky like this.

Inside, he locked the door behind him and slid home the security chain.

The bed in the big bedroom belonged to him now …

but he had never slept in it, and he felt the weight of its strangeness. The bed was made in the same Danish Modern style as the rest of the furniture: subdued, almost generic, as if it had been averaged out of a hundred similar designs; not distinctive but solidly made. He tested the mattress; the mattress was firm. The sheets smelled faintly of clean, crisp linen and not at all of dust.

He thought, I’m an intruder here …

But he frowned at himself for the idea. Surely not an intruder, not after the legal divinations and fiscal blessings of the realty office. He was that most hallowed institution now, a Homeowner. Misgivings, at this stage, were strictly beside the point.

He switched off the bedside lamp and closed his eyes in the foreign darkness.

He heard, or thought he heard, a distant humming … barely audible over the whisper of his own breath. The sound of faraway, buried machinery. Night work at a factory underground. Or, more likely, the sound of his imagination. When he tried to focus on it it vanished into the ear’s own night noises, tinnitus and the creaking of small bones. Like every house, Tom thought, this one must move and sigh with the pulse of its heat and the tension of its beams.

Surrounded by the dark and the buzzing of his own thoughts, he fell asleep at last.

The dream came to him after midnight but well before dawn —it was three a.m. when he woke and checked his watch.