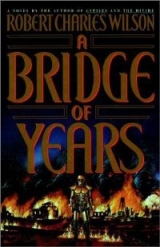

Текст книги "A Bridge of Years"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Fourteen

Tom slept for three hours and woke with Joyce beside him, already feeling as if he’d lost her.

He phoned Max to say he wouldn’t be in. “Maybe I can come in Saturday to make up for it.”

“Are you sick,” Max inquired, “or are you jerking me around?”

“It’s important, Max.”

“At least you’re not lying to me. Very important?”

“Very important.”

“I hope so. This is bothersome.”

“I’m sorry, Max.”

“Take care of your trouble soon, please. You do nice work. I don’t want to break in a new person.”

The trouble wasn’t Joyce. The trouble was in the space between them: that fragile connection, possibly broken.

She was asleep in bed, stretched out on her side with one hand cupping the pillow. The cotton sheet was tangled between her legs. Her glasses were on the orange crate next to the bed; she looked naked without them, defenseless, too young. Tom watched from the doorway, sipping coffee, until she uttered a small, unhappy moan and rolled over.

He couldn’t begin to imagine what all this might mean to her. First the interesting news item that the man she’d been living with was a visitor from the future … followed by an encounter with something strange and monstrous in a tunnel under the earth. These were experiences nobody was supposed to have. Maybe she would hate him for it. Maybe she ought to.

He was turning over these thoughts when she staggered out of the bedroom and pulled up a chair at the three-legged kitchen table. Tom tilled her coffee cup and was relieved that the look she gave was nothing like hateful. She yawned and tucked her hair away from her shoulders. He said, “Are you hungry?” and she shook her head: “Oh, God. Food? Please, no.

Nothing hateful in the way she looked at him, Tom thought, but something new and disquieting: a bruised, wounded awe.

She sipped her coffee. She said she had a gig tonight at a coffeehouse called Mario’s, “but I don’t know if I can face it.”

“Hell of a night,” Tom observed.

She frowned into her cup. “It was all real, wasn’t it? I keep thinking it was some kind of dream or hallucination. But it wasn’t. We could go back to that place and it would still be there.”

Tom said, “It would be. We shouldn’t.” She said, “We have to talk.” He said, “I know.”

They went out for breakfast in the late-morning sunlight and the hot July smell of road tar and sizzling concrete.

The city had changed, too, Tom thought, since last night.

It was a city lost in a well of time, magical and strange beyond knowing, subterranean, more legend than reality. He had come here from a world of disappointment and miscalculation; in its place he had discovered a pocket universe of optimists and cynical romantics—people like Joyce, like Soderman, like Larry Millstein. They said they hated the world they lived in, but Tom knew better. They loved it with their outrage and their poetry. They loved it with the conviction of their own newness. They believed in a future they couldn’t define, only sense—used words like “justice” and “beauty,” words that betrayed their own fundamental optimism. They believed without shame in the possibility of love and in the power of truth. Even Lawrence Millstein believed in these things: Tom had found a carbon copy of one of his poems, abandoned by Joyce in a kitchen drawer; the word “tomorrow” had been printed with fierce pressure—“Tomorrow like a father loves his weary children and gathers them up” —and yes, Tom thought, you’re one of them, Larry, brooding and bad tempered but singing the same song. And of all these people Joyce was the purest incarnation, her eyes focused plainly on the wickedness of the world but seeing beyond it into some kind of salvation, undiscovered, a submerged millennium rising like a sea creature into the light.

All in this hot, dirty, often dangerous and completely miraculous city, in this nautilus shell of lost events.

But I’ve changed that, Tom thought.

I’ve poisoned it.

He had poisoned the city with dailiness, poisoned it with boredom. The conclusion was inescapable: if he stayed here this would become merely the place where he lived, the morning paper and the evening news not miraculous but predictable, as ordinary as the moving of his bowels. His only consolation would be a panoramic, private window on the future, thirty years wide. And Joyce.

Consolation enough, Tom thought … unless he’d poisoned her, too.

He tried to remember what he’d said last night, a drunken recital of some basic history. Too much, maybe. He understood now what he should have understood then: that he wasn’t giving her the future, he was stealing it. Stealing the wine of her optimism and leaving in its place the sour vinegar of his own disenchantment.

He ordered breakfast at a little egg and hamburger restaurant where the waitress, a tiny black woman named Mirabelle, knew their names. “You look tired,” Mirabelle said. “Both of you.”

“Coffee,” Tom said. “And a couple of those Danishes.”

“You don’t need Danishes. You need something to build you up. You need aigs.”

“Bring me an egg,” Joyce said, “and I’ll vomit.”

“Just Danishes, then?”

“That’ll be fine,” Tom said. “Thank you.”

Joyce said, “I want to be alone a little bit today.”

“I can understand that.”

“You’re considerate,” Joyce said. “You’re a very considerate man, Tom. Is that a common thing where you come from?”

“Probably not common enough.”

“Half the men around here are doing a Dylan Thomas thing—very horny and very drunk. They recite the most awful poetry, then get insulted if you don’t go all weak-kneed and peel off your clothes.”

“The other half?”

“Are lovable but queer. You’re a nice change.”

“Thank you.”

“Something’s bothering me, though.”

“That’s not surprising.”

“Tom, I know why you lied to me. That part is understandable. And it wasn’t even really lying—you just kept a few things to yourself. Because you didn’t know whether I would understand. Well, that’s fair.”

He said, “Now you’re being considerate.”

“No, it’s true. But what I don’t understand is why you’re here. I mean, if I found a hole in the ground with the year 1932 at the other end I would definitely check it out … but why would I want to live there? To catch a bunch of Myrna Loy movies, chat with F. Scott Fitzgerald? Maybe get a real close look at Herbert Hoover? I mean, it would be absolutely fascinating, I’ll grant you that. But I have a life.” She shook her head. “I think it would be different if the tunnel ran the other way. I might be really tempted to jump a few decades down the road. But to take a giant step backward—that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

She lit a cigarette. Tom watched the smoke swirl up past her eyes. She had asked an important question; she waited for his answer.

He was suddenly, desperately afraid that he might not have one—that there was nothing he could say to justify himself.

He said, “But if you didn’t have a life … if you had a lousy, fucked-up life …”

“So is that how it was?”

“Yes, Joyce, that’s pretty much how it was.”

“Nineteen sixty-two as an alternative to suicide? That’s a weird idea, Tom.”

“It’s a weird universe. The defense rests.”

Mirabelle arrived with Danishes and coffee. Joyce pushed hers aside as if they were an irrelevancy or a distraction. She said, “Okay, but let me tell you what worries me.”

Tom nodded.

“Back in Minneapolis I went out with a guy named Ray. Ray used to talk about World War Two all the time. We’d go to the movies and then sit at some cheap restaurant while he told me about Guadalcanal or the Battle of Midway. I mean everything, every detail—I can tell you more about Midway than you want to know. So after a while this began to seem kind of strange. One day I asked him how old he was when they dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. Ray says, 1 was twelve —almost thirteen.’ I asked him how he came to know all this stuff about the war and he told me he got it from books and magazine articles. He was never in the army; he was four-F because of his allergies. But that was okay, he said, because there was nothing happening nowadays, nothing like the real war, not even Korea had been like that. He told me how great it must have been, guys risking their lives for a cause they really cared about. I asked him what he would have done if he’d had to invade Italy. He gave me a big smile and said, ‘Shit, Joyce, I’d kill all the Nazis and make love to all the women.’ ”

She exhaled a long wisp of smoke. “My uncle was in Italy. He never talked about it. Whenever I asked him about the war, he got this really unpleasant expression. He’d stare at you until you shut up. So I knew this was basically bullshit. It kind of made me mad. If Ray wanted to live out some heroic existence, why not just do it? It wasn’t even what you could honestly call nostalgia. He wanted some magic transformation, he wanted to live in a world where everything was bigger than life. I said, ‘Why don’t you go to Italy? I admit there’s not a war on. But you could live on the beach, get drunk with the fishermen, fall in love with some little peasant girl’ He said, ‘It’s not the same. People aren’t the same anymore.

Tom said, “Is this a true story?”

“Mostly true.”

“The moral?”

“I thought about Ray last night. I thought, What if he found a tunnel? What if it led back to 1940?”

“He’d go to war,” Tom said. “It wouldn’t be what he expected, and he’d be scared and unhappy.”

“Maybe. But maybe he’d love it. And I think that would be a lot more frightening, don’t you? He’d be walking around with a permanent hard-on, because this was history, and he knew how it went. He’d be screwing those Italian girls, but it would be macabre, terrible—because in his own mind he’d be screwing history. He’d be fucking ghosts. I find that a little terrifying.”

Tom discovered his mouth was dry. “You think that’s what I’m doing?”

Joyce lowered her eyes. “I have to admit the possibility has crossed my mind.”

He said he’d meet her after her gig at Mario’s.

Alone, Tom felt the city around him like a headache. He could go to Lindner’s—but he doubted he could focus his eyes on a radio chassis without passing out. Instead he rode a bus uptown and wandered for a time among the crowds on Fifth Avenue. On a perverse whim he followed a mob of tourists to the 102nd-floor observatory of the Empire State Building, where he stood in a daze of sleep-deprivation trying to name the landmarks he recognized—the Chrysler Building, Welfare Island—and placing a few that didn’t yet exist, the World Trade Center still only a landfill site in the Hudson River. The building where he stood was thirty years old, approximately half as old as it would be in 1989 and that much closer to its art deco glory, a finer gloss on its Belgian marbles and limestone facades. The tourists were middle-aged or young couples with children, men in brown suits with crisp white shirts open at the collar, snapping photos with Kodak Brownies and dispensing dimes to their kids, who clustered around the ungainly pay-binoculars pretending to strafe lower Manhattan. These people spared an occasional glance for Tom, the unshaven man in a loose sweatshirt and denims: a beatnik, perhaps, or some other specimen of New York exotica. Tom looked at the city through wire-webbed windows.

The city was gray, smoky, vast, old, strange. The city was thirty years too young. The city was a fossil in amber, resurrected, mysterious life breathed into its pavements and awnings and Oldsmobiles. It was a city of ghosts.

Ghosts like Joyce.

He shaded his eyes against the fierce afternoon sun. Somewhere in this grid of stone and black shadow, he had fallen in love. This was certain knowledge and it took some of the sting from what Joyce had said. He wasn’t fucking ghosts. But he might have fallen in love with one.

And maybe that was a mistake; maybe he’d be better off fucking ghosts. He tried to recall why he had come here and what he had expected. A playground: maybe she was right about that. The sixties—that fabled decade—had ended when he was eleven years old. He’d grown up believing he’d missed something important, although he was never sure what—it depended on who you talked to. A wonderful or terrible time. When the Vietnam War was fought in, or against. When drugs were good, or weren’t. When sex was never lethal. A decade when “youth” was important; by the time of Tom’s adolescence the word had lost some of its glamour.

Maybe he had expected all these wonders assembled together, served with a side of invulnerability and private wisdom. A vast phantom drama in which he was both audience and actor.

But Joyce had made that impossible.

He had come here wanting love—some salvaging grace– but love was impossible in the playground. Love was a different landscape. Love implied loss and time and vulnerability. Love made all the props and stage sets too real: real war, real death, real hopes invested in real lost causes.

Because he loved her he had begun to see the world the way she did: not the gaudy Kodachrome of an old postcard but solid, substantial, freighted with other meanings.

He raised his eyes to the horizon, where the hot city haze had begun to lift into a comfortless blue sky.

He bought dinner at a cafeteria and showed up at Mario’s, a basement cafe under a bookstore, before Joyce was due on stage. The “stage,” a platform of two-by-fours covered with plywood panels, contained a cane-backed chair and a PA microphone on a rust-flecked chromium stand—not strictly necessary, given the size of the venue. Tom chose a table by the door.

Joyce emerged from the shadows with her twelve-string Hohner and a nervous smile. Out of some tic of vanity she had chosen to leave her glasses offstage, and Tom was mildly jealous: the only other time he saw her without her glasses was when they were in bed together. Without them, under the stage lights, her face was plain, oval, a little owl-eyed. She blinked at her audience and pulled the microphone closer to the chair.

She began without much confidence, letting the guitar carry her—more certain of her fingers than of her voice. Tom sat among the quieting crowd while she ran a few arpeggios and chord changes, pausing once to tune a string. He closed his eyes and appreciated the rich body of the Hohner.

“This is an old song,” she said.

She sang “Fannerio,” and Tom felt the piercing dissonance of time and time: here was this long-haired woman in a Village cafe playing folk ballads, an image he associated with faded Technicolor movies, record jackets abandoned at garage sales, moldering back issues of Life. It was a cliche and it was painfully naive. It was quaint.

But this was Joyce, and she loved these words and these tunes.

She sang “The Bells of Rhymney” and “Lonesome Traveler” and “Nine Hundred Miles.” Her voice was direct, focused, and sometimes inconsolably sad.

Maybe Larry was right, Tom thought. We love them for their goodness, and then we scour it out of them.

What had he given her, after all?

A future she didn’t want. A night of stark terror in a hole under Manhattan. A burden of unanswerable questions. He had come into her life like a shadow, the Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come, with his bony ringer pointed at a grave.

He wanted her optimism and her intensity and her fierce caring, because he didn’t have any of his own … because he had mislaid those things in his own inaccessible past.

She sang “Maid of Constant Sorrow” under a blue spot, alone on the tiny stage.

Tom thought about Barbara.

The applause was generous, a hat was passed, she waved and stepped back into the shadows. Tom circled around behind the stage, where she was latching the Hohner into its shell. Her face was somber.

She looked up. “The manager says Lawrence called.”

“Called here?”

“Said he’d been trying to get hold of us all day. He wants us to go over to his apartment and it’s supposed to be urgent.”

What could be urgent? “Maybe he’s drunk.”

“Maybe. But it’s not like him to phone here. I think we should go.”

They walked from the cafe, Joyce hurrying ahead, obviously concerned. Tom was more puzzled than worried, but he let her set the pace.

They didn’t waste any time. They arrived too late, anyhow.

There was a crowd in the stairwell, a siren in the distance —and blood, blood in the hallway and blood spilling from the door of Millstein’s apartment, an astonishing amount of blood. Tom tried to hold Joyce back but she broke away from him, calling out Lawrence’s name in a voice that was already mournful.

Fifteen

Armored, alert, and fully powered, Billy identified the scatter of blue luminescence on the apartment door and adjusted his eyepiece to wideband operation. His heart was beating inside him like a glorious machine and his thoughts were subtle and swift.

The corridor was empty. The keen apparatus of Billy’s senses catalogued the smell of cabbage, roach powder, mildewed linoleum; the dim floral pattern of the wallpaper; the delicate tread and pressure of his feet along the floor.

He burned open the lock with a finger laser and moved through the doorway with a speed that caused the hinges to emit a squeal, as of surprise.

He closed the door behind him.

The apartment was long and rectangular, with a door open into what appeared to be the kitchen and another door, closed, on what was probably a bedroom. A window at the far end of the rectangle showed the night silhouette of the Fourteenth Street Con Edison stacks through a burlap curtain tied back to a nail. The wall on the left was lined with bookshelves.

The room was empty.

Billy stood for a silent moment, listening.

This room and the kitchen were empty … but he heard a faint scuffle from the bedroom.

He smiled and moved through that door as efficiently as he had moved through the first.

This room was smaller and even shabbier. The walls were dirty white and bare except for a crudely framed magazine print of an abstract painting. The bed was a mattress on the floor. There was a man in the bed.

Billy ceased smiling, because this wasn’t the man he had followed from Lindner’s.

This was some other man. This was a tall, pigeon-chested, naked man snatching a cotton sheet over himself and squinting at Billy in the darkness with gap-jawed astonishment.

The man on the mattress said, “Who the fuck are you?”

“Get up,” Billy said.

The man didn’t get up.

He doesn’t know what I am, Billy realized. He thinks I’m an old man in a pair of goggles. It’s dark; he can’t see very well. Maybe he thinks I’m a thief.

Billy corrected this impression by burning a hole in the mattress beside the naked man’s outstretched left arm. The hole was wide and deep. It stank of charred kapok and cotton and the waxy smoke of the wood floor underneath. The hole was black and began immediately to burn at the edges; the naked man yelped and smothered the flames with his blanket. Then he looked up at Billy, and Billy was pleased to recognize the fear in his eyes. This was the kind of fear that would make him abject, malleable; not yet a panicked fear that would make him unpredictable.

“Stand up,” Billy repeated.

Standing, the man was tall but too thin. Billy disliked his fringe of beard, the bump of his ribs, the visible flare of his hip bones. His penis and shriveled scrotum dangled pathetically between his legs.

Billy imagined burning away that sack of flesh, altering this man in something like the way the Infantry doctors had altered Billy himself … but that wasn’t good strategy.

Billy said, “Where’s the man who lives here?”

The naked man swallowed twice and said, “I’m the man who lives here.”

Billy walked to the wall and switched on the light. The light was a sixty-watt bulb hanging on a knotted cord, smoke from the charred mattress swimming around it. Billy’s eyepiece adapted at once to this new light, damping its amplification. The naked man blinked and squinted.

He stared at Billy. “My God,” he said finally. “What are you?

Billy knew the question was involuntary and didn’t require an answer. He said, “Tell me your name.”

“Lawrence Millstein,” the naked man said. “Do you work at a shop called Lindner’s Radio Supply?”

“No.”

This was true. Billy heard its trueness in the quaver of the man’s voice; in the overtones of his terror. “Do you live here alone?”

“Yes.”

This was true, also.

“A man came here from Lindner’s,” Billy said. “Do you know a man who works at Lindner’s?”

“No,” Lawrence Millstein said.

But this was a lie, and Billy responded to it instantly: he narrowed the beam of his wrist weapon and used it to slice off the tip of Lawrence Millstein’s left-hand index finger at the top knuckle. Millstein stood a moment in dumb incomprehension until the pain and the stink of his own charred flesh registered in his brain. He looked down at his wounded hand.

His knees folded and he sank back to the ruined mattress. Billy said reproachfully, “You know the man I mean.”

“Yes,” Millstein gasped.

“Tell me about him,” Billy said.

All this reminded Billy of that time long ago, in the future, in Florida, and of the woman who had died there.

Those memories welled up in him while he extracted Lawrence Millstein s confession.

Billy remembered the shard of glass and the woman’s name, Ann Heath, and the way she had repeated it to herself, Ann Heath Ann Heath, with the blood on her face and throat and soaking the front of her shirt like a bright red bib.

He had come northwest from the ruins of Miami with his comrades Hallo well and Piper, a fierce storm on their heels. Cut out of their platoon in an ambush, they had retreated in the face of superior fire through a maze of suburban plexes and windowless pillbox dwellings whipped by a torrent of wild ocean air, the barometer low and falling. The night was illuminated by arcs of lightning along the eastern horizon, where a wall of cloud rotated around the fierce vacuum of its core. They ran and didn’t much speak. They had given up hope of finding friendly territory—they wanted only some space between themselves and the insurgency before they were driven to shelter.

Billy had grown used to the wind like a fist at his back by the time they saw the house.

It was a house much like all the other houses on this littered empty street, a low bunker of the type advertised as “weatherproof” after the first disasters in the Zone. Of course, it wasn’t. But its roof was intact and the walls seemed secure and defensible and it must have survived a great many storms relatively intact. It was whole; that was what drew Billy’s attention.

Most of these buildings were empty, but there was always the possibility of squatters; so Brother Hallowell, a tall man and thick-chested under his armor, vaulted a chain fence and circled to the back while Billy and Brother Piper launched a concussion weapon through the narrow watch slot next to the door. Billy grinned as the door whooshed open and white smoke billowed out into the rain. He stepped inside and felt his eyepiece adjust to the darkness; he pulled a pocket extinguisher from his belt and doused the burning carpet. Brother Piper said, “I’ll do the back door for Brother Hallowell,” and started for the rear of the house while Billy sealed the front against the gusting rain, thinking how good it would be to be dry for a night … but then things turned strange very quickly. Brother Piper began shouting something incomprehensible, Brother Hallowell thumped at the rear door, while machine bugs came pouring out of the walls, out of hiding places in the plasterboard, from crates and boxes Billy had mistaken for squatters’ refuse—thousands of glistening jewel-like creatures Billy could only dimly identity as mechanical. Brother Piper screamed as they swarmed up his legs. Billy had heard of Brazilian weapons imported by the insurgents, tiny poisonous robots the size of centipedes, and he reached by instinct for the machine-killer on his belt: a pulse bomb the size of a walnut, which he triggered and tossed against the far wall; it exploded without much concussion but with a burst of electromagnetic radiation strong enough to overload anything close. Even Billy’s armor, which was hardened against such pulses, seemed to hesitate and grow heavy; his eyepiece dimmed and read him nonsense numbers for a long second. When his vision cleared the machine bugs were silent and motionless. Brother Piper was shaking them off his leg in a wild dance. Then Brother Hallowell, who was their CO, came through a doorway from the back and said, “What the fuck? I had to dump two pulses just to get in here and I put a third downstairs—this place has a big cellar. Brother Billy, do you know what these little bugs are?”

Billy was the youngest but he read a lot; Piper and Hallowell always asked him questions like that. This time he was stumped. “Sir, I don’t,” Billy said.

Brother Hallowell shrugged and said, “Well, we walked into something peculiar for sure. You know there’s a lady in the next room?”

Billy was reluctant to take a step forward; he didn’t relish the sound of the machine bugs crunching under his feet. “A lady?”

“That’s right,” Brother Hallowell said, “but your concussion grenade just about took her out, Brother Billy. She has a wedge of plate glass in her head. She’s not dead, and her eyes are open, but—well, come look.”

Billy was dazed but his armor kept him functioning. Even Brother Piper was beginning to calm down. The elytra came back up to full function and Billy felt as if his blood had cooled by two or three degrees. Maybe this place was a weapons dump; maybe they’d get a commendation for discovering it. This was a pleasant idea but Billy disbelieved it even as he thought it—the machine bugs were too strange a product even for the Brazilian ordinance makers.

He followed Brother Hallowell to the next room, where the woman lay slumped in a corner between two boxes. The concussion grenade had slivered a glass dividing wall and driven one long green-tinted wedge into the woman’s head between her right ear and her right eye. There was blood, but not as much as Billy had expected. The sight of this young woman with the shank of plate glass projecting from her cranium like a ghastly party hat took Billy strangely; he reached down to touch the glass—a gesture of awe—and as he touched it the woman blinked and gasped … not in pain, Billy thought, but as if the tremor of his touch had ignited some pleasant memory, long forgotten. She looked up at Billy with one eye, the left. The right eye, bloodshot, gazed indifferently at some vision not physically present.

“What’s your name?” Billy asked.

“Ann Heath,” the woman said plainly.

“Back off now.” Billy stepped away as Brother Hallowell took a medical package out of his pack and selected a cardiovascular unit. He tore away the woman’s shirt, then clamped the wound unit between her breasts. When he switched it on Billy heard the hemotropic tubes crunch into Ann Heath’s body, a terrible sound. “Oh,” she said calmly, as the wound unit began to regulate her breathing. Now she wouldn’t die even if her heart and lungs gave out, though she still might become comatose. Billy understood the purpose of this maneuver: to keep her interrogatable for a little while longer.

Brother Hallowell gave the machine a moment to stabilize, then bent down over Ann Heath. “Ma’am,” he said, “can you tell me exactly what this place is?”

Ann Heath responded obediently, as if the shard of glass had severed the part of her brain governing caution and left only obedience:

“A time machine,” she said.

Brother Hallowell looked almost comically perplexed. “A what?”

“A time machine,” Ann Heath said. The cardiovascular machine put a tremor in her voice, as if she had a bad case of the hiccups.

Brother Hallowell sighed. “She’s scrambled,” he said.

“She’s brain dead.” He straightened and flexed his back.

“Brother Billy, will you interrogate the prisoner? See if you can get anything coherent out of her. Meanwhile Brother Piper and I will reconnoiter and try to get some power going.

Wind rocked the building. Billy sat down next to the injured woman and pretended not to see the wedge of green glass in her head. He waited until Brother Hallowell and Brother Piper had left the room.

Ann Heath didn’t look like a liar to him. In her condition, Billy thought, it might not be possible to tell a lie.

He said, “Is this building really a time machine?”

“There’s a tunnel in the basement,” Ann Heath said, tonelessly, except for the hiccupping. “Where does it go?” Billy asked. “The future,” she said. “Or the past.”

“Tell me about it,” Billy said.

The storm penned them in the house for two days. Ann Heath grew steadily less intelligible; but in that time, while Brother Hallowell and Brother Piper were cleaning their armor, or heating rations over the building’s thermopump, or playing card games, Billy did as he was told: he interrogated the prisoner. He explained to Piper and Hallowell that she was incoherent but he hoped she might still say something useful. Piper and Hallowell didn’t really care what she said. They had swept aside the dead machine bugs and seemed to have written them off as some Storm Zone aberration, something the research corps might be interested in—later. Neither Piper nor Hallowell enjoyed mysteries. Nor did Billy; but Billy believed what Ann Heath told him.

What Ann Heath told him was a catalogue of miracles. She told it without passion and with great clarity, as if a door had come unlocked in her head, the answers to Billy’s questions spilling out like hoarded treasure.

Late on the third night of their occupation, while the storm plucked at the edges of the house and Brother Hallowell and Brother Piper dozed in the placid heat of their armor, Billy took Ann Heath down to the basement. Ann Heath couldn’t walk by herself, the left side of her body curling out from under her as if the joints wouldn’t lock, so Billy put an arm around her and half carried her, getting his hands all bloody on the mess of her shirt. He was disappointed by the basement, because it was as plain a cell as the upstairs rooms —no miracles here that he could see. Billy had retained the edge of his skepticism throughout this interrogation and the basement seemed to confirm all his doubts. But then she showed him the control panel set into the blank wall, invisible until she spoke a word in a language Billy didn’t recognize; then he held his own hand against the panel while she spoke more words until the panel knew Billy’s touch. She taught him which words to say to operate the machine, and Billy and his armor memorized the peculiar sounds. Then her head dropped and she started to drool and Billy put a pillow of wadded rags behind her so she could sleep—if this was sleeping—while the cardiovascular unit bumped steadily against her breastbone. Billy opened the tunnel—it appeared at once, white and miraculous, his final assurance that these miracles were genuine—then he closed it again. Ann Heath had told him how she was getting ready to close this tunnel forever, and Billy wondered what it would have been like if he and Brother Piper and Brother Hallowell had passed by this place and found some other shelter: he would never have guessed, never imagined, lived out his life never knowing about tunnels between time and time. He thought about this and about Ohio and about the Infantry and how much he hated it. He thought about his armor; then he powered his armor up and moved upstairs to the place where Brother Piper and Brother Hallowell were sleeping, and he put his gloved hand down close to Brother Piper’s exposed head and beamed a smoky corridor through Brother Piper’s skull, then turned and did the same to Brother Hallowell before he was altogether awake; then he ran back downstairs, hurrying because he was afraid this peculiar, mutinous courage might evaporate and leave him weeping.