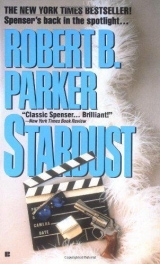

Текст книги "Stardust"

Автор книги: Robert B. Parker

Жанр:

Крутой детектив

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

Chapter 21

THE drive down the San Diego Freeway from LAX takes about two and a half hours and seems like a week. Once you get below the reaches of L.A.’s industrial sprawl, the landscape is sere and unfriendly. The names of the beach towns come up and flash past and recede: Huntington Beach, Newport Beach, Laguna, San Clemente. But you can’t see them from the freeway. Just the signs and the roads curving off through the brownish hills.

Mindy had gotten me a hotel room at the Hyatt Islandia in Mission Bay, and I pulled in there around 3:30 in the afternoon with the temperature at eightysix and the sky cloudless: They assigned me a room in one of the pseudo-rustic cabanas that ran along the bay, as a kind of meandering wing to the tall central hotel building. I stashed my bag, got my list of addresses and my city map, and headed back out to work.

San Diego, like San Francisco, and like Seattle, seems defined by its embrace of the sea. The presence of the Pacific Ocean is assertive even when the ocean itself is out of sight. There is a different ambient brightness where the steady sunshine hits the water and diffuses. The bay, the Navy, the bridge to

Coronado seemed always there, even when you couldn’t see them.

Of my three Zabriskies, two lived downtown; the third was up the coast a little in Esmeralda. The first one was a Chief Petty Officer who was at sea on a carrier. His wife said he didn’t have any sisters, that his mother was in Aiken, South Carolina, and that she herself never watched television. The second was a Polish émigré who had arrived from Gdansk fourteen months ago. It took me into the evening to find that out. I had supper in a place near the hotel, on the bay, that advertised fresh salmon broiled over alder logs. I went in and ate some with a couple of bottles of Corona beer (hold the lime). It wasn’t as good as I had hoped it would be; it still tasted like fish. After supper I strolled back to the hotel along the bayfront, past the charter boat shanties and the seafood take-out stands that sold ice and soda. Across the expressway, gleaming with light in the murmuring subtropical evening, the tower of Sea World rose above the lowland where the bay had bcco created. It was maybe 9:30 on the coast, and halt past midnight on my eastern time sensor. Susan would be asleep at home, the snow drifting harmlessly outside her window. She would sleep nearly motionless, waking in the same position as she’d gone to sleep. She rarely moved in the night. Jill Joyce would have gone to sleep drunk, by now; and she would wake up clear-eyed and innocent-looking in the morning to go in front of the camera and charm the hearts of America. Babe Loftus wouldn’t.

In my cabana I undressed and hung my clothes up carefully. There was nothing on the tube worth watching. I turned out the light and lay quietly, three thousand miles from home, and listened to the waters of the bay murmur across from my window, and smelled the water, a mild placid smell in the warm, faraway night.

Chapter 22

ESMERELDA is in a canyon on the north edge of San Diego. It nestles against the Pacific Ocean with the hills rising behind it to cut off the rest of California as if it didn’t exist. Esmeralda was full of trees and gardens and flowers. The downtown lounged along the coastline, a highlight of stucco and Spanish tile and plate glass and polished brass clustered near Esmeralda cove. One would never starve in Esmeralda. Every third building along the main drag was a restaurant. The other ones sold jewelry and antiques and designer fashions. The pink stucco hotel in the middle of the main drag had a big canopied patio out front and a discreet sign that said CASA DEL PONIENTE, Three valet carhops stood alertly outside in black vests and white shirts waiting to do anything you told them to do. I nosed in and parked in front of a bookstore across the street from the hotel. According to my map, Polton’s Lane ran behind the stores that fronted Main Street. I left the car and walked back to the corner and turned left on Juniper Avenue. The street was lined with eucalyptus trees that sagged heavily, their branches nearly touching the ground in some places. There was a luggage shop, the window display a single suitcase with a fuchsia silk scarf draped over it. The suitcase and scarf sat on a black velvet background under a small spotlight. Beyond the luggage store was a discreet real estate office done in pale gray and plum, with color pictures, well mounted, of oceanfront property displayed in the window. Between the two buildings was Polton’s Lane. The name was too grand. It was an alley. Behind the stores, cartons and trash barrels were piled, overflowing in some cases. Two cats, a yellow tom with tattered ears, and something that had once been mostly white, scuttled out of sight, their tails pointed straight out as they hurried away.

The alley widened into a small vacant lot encircled by the back doors of affluence. In the lot were several small frame shacks, probably one room apiece, with low board porches across the front. To each had been attached a lean-to which probably was a bathroom. The yard in front of the one nearest to me was bare dirt. The rest of the lot was weeds. The rusting hulk of a car that might once have been a Volvo stood doorless and wheelless among the weeds, and beyond it someone had discarded a hot water heater. A line of utility poles preceded me down the alley, and wires swung lax between the poles and each house. I stood staring at this odd community of hovels, built perhaps before the town had acquired a main street; built maybe by the workers who built the main street. Here and there among the weeds were automobile tires and beer cans, and at least one mattress with the stuffing spilled out.

My address was number three. Once, a long time ago, someone had tried to make a front path of concrete squares set into the ground. Now they were barely visible among the weed overgrowth. From the house came the sound of a television set blaring a talk show. On the front porch a couple of green plastic bags had torn open, and the contents spilled out onto the porch floor. It didn’t look as if it had happened recently. It was hot in the backside of Esmeralda, and in the heat the rank smell of the weeds mixed with whatever had rotted in the trash bags. I maneuvered around the trash and knocked on the screen door that hung loose in its hinges from a badly warped doorjamb. Nothing happened. I knocked again. Through the screen, which was, it seemed, the only door, I could see a steel-framed cot, with a mattress and a pink quilt and a pillow with no pillowcase. Next to it was a soapstone sink, and in front of both was a metal table that had once been coated with white enamel. To the right of the door I could see the hack of what might have been a rocking chair. It moved a little and then a woman appeared in the doorway. The smell of booze came with her, overpowering the smell of the weeds and the hot barren earth.

“Yuh,” she said.

She was an angular woman with white hair through which faded streaks of blond still showed. The hair hung straight down around her face without any hint of a comb. She had on a tee shirt that advertised beer, and a pair of miracle fiber slacks that had probably started out yellow. Her feet were bare.

In her right hand she was carrying a bottle of Southern Comfort, her skinny, blue-veined hand clamped around its neck.

“Spenser,” I said. “City Services. Open up.” The door was hooked shut, although the screening in front of it was torn and I could have reached in and unhooked it myself.

She nodded slowly, staring at me through the door. Her face had not seen make-up, or sun, for a long time. It sagged along her jawline, and puckered at the corners of her mouth. Her eyes were darkly circled and pouchy. In the hand that didn’t hold the Southern Comfort was a cigarette, and she brought it up slowly, as if trying to remember the way, and took a big suck on it.

“Vera Zabriskie?” I said. I made it sound officious and impatient. Women like Vera Zabriskie were used to civil servants snapping at them. It was what they endured in return for the welfare check that kept them alive. She looked at me, still frowning, as she let the smoke drift out of her mouth. Then she took a slug of Southern Comfort from the bottle and swallowed.

“Yuh,” she said.

“You’re Vera?” I said. She nodded.

“Well, then, damn it, let me in. You think I got all day?”

She thought about what I’d said, turned it around a little in her head, got a look at it, and figured out, slowly, what it meant. Still holding the cigarette between the first two fingers, she raised a hand and fumbled the hook out of the door. She stepped back. I pushed it open and went in. The place smelled bad, a scent compounded of garbage, sweat, booze, cigarette smoke, and loss. A huge color television set was blatting at me from the corner. On top of the television set, framed in one of those cardboard holders that school pictures come in, was a color picture of Jill Joyce on the cover of TV Guide. The picture didn’t fit the frame right, and it had been adjusted with Scotch tape here and there. Can this be a clue I see before me?

Vera Zabriskie went back to her rocking chair and sat in it and took a pull on the Southern Comfort bottle, and stared at the tube. It stared back with about the same level of comprehension. She dropped her burning cigarette on the floor and stamped aimlessly at it and half squashed it. The crushed butt continued to smolder. The floor around her chair was littered with sniped cigarettes and burn marks in the unfinished plywood.

I went around and turned off the television. She showed no reaction. She continued to look at the blank screen.

I said, “Who’s the woman in the picture?”

Her head turned slowly toward me. She squinted a little. She raised her left hand and realized there was no cigarette and stopped, put the bottle of Southern Comfort on the floor, picked up a pack of Camels from the floor and got another cigarette burning. She inhaled deeply, put down the pack, picked up the jug, and stared at me again.

“Who’s the woman in the picture?” I said.

“Jillian.”

“Jillian who?” I said. I still had my official tone.

“Jillian Zabriskie,” she said with no inflection. “I seen the name on a TV show.”

“She related to you?”

“Daughter,” she said. There was a sound in her voice that I hadn’t heard before. It was weak but it might have been pride. I looked around the oneroom shack where Vera Zabriskie lived. She saw me look around. I saw her see me. We stared for a moment at each other, like two actual humans. For a moment a real person lurked inside the mask of alcohol and defeat, and peered out at me through the rheumy blue eyes. For a moment I wasn’t a guy pumping her for information.

“You’re not close with your daughter,” I said.

Vera suddenly heaved herself up out of the rocker. She put the cigarette in her mouth and put the bottle on the chipped enamel table. She opened the drawer in the table and rummaged with both hands, and came out with another picture.

It was framed in cardboard, like the picture of Jill, only this one was a school picture. Vera handed it to me. It was a picture of a little girl, maybe ten. Dark hair, dark eyes, olive skin, and a clear resemblance to Jill Joyce.

“Who’s this?” I said. “Granddaughter,” she said.

“Jillian’s daughter?” I said.

“Yuh.”

I looked at the picture again. In the indefinable way that pictures speak, this one was telling me it wasn’t recent.

“How old is she now?” I said.

“Jillian?”

“No, your granddaughter.”

The burst of humanity had drained her. She was back in the rocker, with her bottle. She shrugged. Her gaze was fixed on the blank picture tube. I slipped the picture out of its holder and put it inside my shirt. Then I folded the cardboard and put it back in the drawer.

“You see her much?” She shook her head. “She live around here?”

She shook her head again. She drank a little Southern Comfort from the bottle.

“Far away?” She nodded. “Where?”

“L.A.,” Vera said. Her voice was flatter than a tin shingle.

“She with her dad?” I said. Sincere, interested in Vera’s family. You’re in good hands with Spenser. Vera shrugged.

“What’s her dad’s name?”

“Greaser,” Vera said clearly.

“Odd name,” I said.

“Told her stay away from that greaser. Took my granddaughter.”

“What did you say his name was?”

“Spic name.”

“Un huh,” I said helpfully.

“Told her not.”

“What’s his name?” The helpful smile stretched across my face like oil on water. I could feel the tension behind my shoulders as I tried to squeeze blood from this stone.

“Victor,” she said. “Victor del Rio.”

“And he lives in L.A.”

“Yuh.”

“You know where?” She shook her head. “You ever see your granddaughter?”

She shook her head again. She was frowning at the blank television, as if the fact of its gray silence had just begun to penetrate. She leaned forward in the rocker and turned it on. Then, exhausted by the effort of concentration, she leaned back in the rocker and took a long pull of her Southern Comfort. The talk show had given way to a game show; photogenic contestants frantic to win the money, a faintly patronizing host, amused by their greed.

I stood silently beside the seated woman lost in her television and her booze. She was inert in her chair, occasionally dragging on the cigarette, occasionally pulling on the bottle. She seemed to have forgotten I was there. I had other questions, but I couldn’t stand to ask them. I couldn’t stand being there anymore. I turned and went to the door and stopped and looked back at her. She sat motionless, oblivious, her back to me, her face to the television.

I opened my mouth and couldn’t think what to say and closed it, and went out into the putrid weed smell and walked back out Polton’s Lane, trying not to breathe deeply.

Chapter 23

FROM the Hyatt in Mission Bay, I called Mindy at the Zenith Meridien production office in Boston.

“The trail,” I said, “leads to L.A., sweetheart.”

“Are you doing Cary Grant?” she said.

“You got some smart mouth, sweetheart. No wonder you’re not an executive.”

“It’s not a smart mouth that gets a girl ahead in this business, big guy.”

“Cynicism will age you,” I said.

“So will you. You want a hotel in L.A.?”

“Yes, please.”

“Zenith always puts people up at the Westwood Marquis,” Mindy said. “Okay with you?”

“I’ll make do,” I said.

“Okay. Corner Hilgard and LeConte, in Westwood Village.”

“I’ll find it,” I said.

“Super sleuth,” she said, and hung up.

I checked out of the Islandia and headed back up the freeway. Having a production coordinator wasn’t bad. Maybe I should employ one. I needed a hotel reservation and airline bookings every two, three years. In between times she could balance my checkbook.

The drive from San Diego to L.A. is not much more interesting than the drive from L.A. to San Diego. While I drove, I thought about what I was doing. As usual I was blundering around and seeing what I could kick up. So far I’d kicked up a child and another significant other in Jill Joyce’s life.

So what?

So I hadn’t known that before.

So how’s it help?

How the hell do I know?

The Westwood Marquis had flower gardens and two swimming pools and a muted lobby and served tea in the afternoon. All the rooms were suites. Zenith Meridien must be doing okay.

Everybody I saw in the lobby was slender and tended to Armani sport coats with the sleeves pushed up. I had on jeans and a sweatshirt with the sleeves cut off. My luggage was a gray gym bag with ADIDAS in large red letters along the side. I felt like a rhinoceros at a petting zoo.

I unpacked in my pale rose room and took a shower. Then I called an L.A. cop I knew named Samuelson and at 3:30 in the afternoon I was in my rental car heading downtown, on Wilshire.

The homicide bureau was located in the police building on Los Angeles Street. Samuelson’s office looked like it had eight years ago when I was in there last. There was a desk, a file cabinet, an air conditioner under the window behind Samuelson’s desk. The air conditioner was still noisy and there was still something wrong with the thermostat because it kept cycling on and shutting off as we talked. Samuelson appeared not to notice. He was a tall guy, nearly bald, with a droopy mustache and tinted aviator-style glasses. His corduroy jacket hung on a hook on a hat rack behind the door. Beyond the glass partition the homicide squad room spread out like squad rooms in every city. They all seemed to have been designed from the same blueprint.

“Probably a squad room on Jupiter,” I said, “looks just like this.”

Samuelson nodded. He had on a white shirt and a red and blue striped tie with the tie at half mast and the collar unbuttoned. He leaned back in his swivel chair and put his hands behind his head. He wore his gun high on his belt on the right side.

“Last time I saw you,” Samuelson said, “you’d finished fucking up a case of ours.”

“Always glad to help out,” I said.

“So what do you need?” Samuelson said.

“I’d like to talk with a guy named Victor del Rio.”

Samuelson showed no reaction.

“Yeah?” he said.

“He’s not listed in the L.A. book,” I said. “I was wondering if you had anything on him.”

“Why do you want to talk with him?” Samuelson said.

“Would you buy, ‘it’s confidential’?”

“Would you buy, ‘get lost’?”

“I’m backtracking on a murder in Boston; del Rio was once intimate with a figure in the case. He fathered her daughter.”

“And the figure?” Samuelson was perfectly patient. He was used to asking. He learned everything he knew this way. One answer at a time, nothing volunteered. If he minded it didn’t show.

“Jill Joyce,” I said.

“TV star?”

“Un huh.”

“You private guys get all the glamour work,” Samuelson said. “She try to bang you yet?”

“Ah, you know Miss Joyce,” I said.

Samuelson shrugged. “Victor del Rio runs the Hispanic rackets in L.A.”

“That’s heartwarming,” I said. “A success story.”

“Yeah, a big one,” Samuelson said.

“So where do I find him?” I said.

“If you annoy del Rio you will be in bigger trouble than I can get you out of,” Samuelson said.

“Why do you think I’ll annoy him?” I said.

“Because you annoy me,” Samuelson said. “And I’m a cupcake compared to del Rio. You got a gun?”

“Yes.”

“You licensed in California?”

“No.”

“Of course not,” Samuelson said. “Del Rio’s got a place in Bel Air.”

“Not East L.A.?”

“Are you kidding,” Samuelson said. “That’s where he makes his money. It’s not where he lives.”

“You got an address?”

“Wait a minute,” Samuelson said. He picked up the phone and spoke into it. Outside in the main squad room an L.A. cop with his handcuffs dangling from his shoulder holster was talking to an Hispanic kid wearing a bandanna wrapped around his head. The cop would lean forward every once in a while and tilt his head up to full face by chucking him firmly under the chin. The kid would hold the gaze for a moment and then his head would drop again.

Samuelson hung up and scribbled an address on a piece of paper. He handed me the paper.

“Off Stone Canyon Road, you know where that is?” he said.

“Yeah.”

“Don’t give del Rio a lot of lip,” Samuelson said. “I’m overworked now.”

I stood and tucked the address into my shirt pocket.

“Thanks,” I said.

“I can’t give you a lot of help with del Rio,” Samuelson said. “He is very connected.”

“Me too,” I said. “Detective to the stars.”

Chapter 24

BEL Air had its own gate, opposite the point where Beverly Glen jogs on Sunset. There was a gatehouse and alert members of the Bel Air patrol in evidence. I went past the gate on Sunset and turned into Stone Canyon Road. There was no gate, no members of the private patrol. i was always puzzled why they bothered with the gatehouse. Stone Canyon Road wound through trees and crawling greenery all the way up to Mulholland Drive. I wasn’t going that far. About a mile in I turned off the drive onto a side road and 100 yards farther I turned in between two beige brick pillars with huge wroughtiron lanterns on the top. I stopped. There was a big wrought-iron gate barring the way. Beyond the gate a black Mercedes sedan with tinted windows was parked. I let my car idle. On the other side of the gate the Mercedes idled. The temperature was ninety. Finally a guy got out of the passenger side of the Mercedes and walked slowly toward the gate. He wore a black silk suit of Italian cut and a white dress shirt buttoned to the neck, no tie. His straight black hair was slicked back in a ducktail, and his face had the strong-nosed look of an American Indian.

He stood on the inside of the gate and gestured at me. I nodded and got out of the car.

“Name’s Spenser,” I said. “I’m working on a case in Boston and I need to see Mr. del Rio.”

“You got some kind of warrant, Buck?” His voice had a flat southwestern lilt to it. He spoke without moving his lips.

“Private cop,” I said and handed him a business card through the gate. He didn’t look at it. He simply shook his head at me.

“Vamoose,” he said.

“Vamoose?”

“Un huh.”

“Last time I heard someone say that was on Tom Mix and his Ralston Straight Shooters.”

The Indian wasn’t impressed. He gestured toward my car with his thumb, and turned and started away.

“Tell your boss it’s about somebody named Zabriskie,” I said.

The Indian stopped and turned around.

“Who the hell is Zabriskie,” he said, “and why does Mr. del Rio care?”

“Ask him,” I said. “He’ll want to see me.”

The Indian paused for a moment and pushed his lower lip out beyond his upper.

“Okay,” he said, “but if you’re horsing around with me I’m going to come out there and put your ass on the ground.”

“You don’t sound like a Ralston Straight Shooter,” I said.

The Indian tapped on the window on the driver’s side. It rolled down silently. He spoke to the driver, and the driver handed him a phone. The Indian spoke on the phone again and waited, and spoke again. Then he listened. Then he handed the phone back inside the Mercedes and walked toward the gate. The gate swung open as he walked toward it. “I’ll ride up with you,” he said.

“How nice,” I said.

We got in my car and headed up the drive. The gate swung silently shut behind us. The roadway wound uphill through what looked like pasture land. Trees defined the borders of the property, but inside the borders was smooth lawn and green grass grew thickly under the steady sweep of a sprinkler system. To my left a young woman on a white horse came up over the crest of a low hill and reined in the horse and watched as the car went past. Then we came around another turn in the road and there was the house, a long, low structure with many wings that sprawled over the top of the next hill in a kind of undulating ramble. It was white stucco with the ends of the roof beams exposed.

“Park over there,” the Indian said.

I put the rental car in a turnaround that was paved with crushed oyster shells and we got out and walked back toward the house. The Indian rang the doorbell.

We waited.

The front door was made to look as if it had been hammered together from old mesquite wood and had probably cost $5,000. The plantings along the foundation of the house were low and tasteful and tended to bright red flowers. I could smell the flowers, and the grass, and a hint of water flowing somewhere, and even fainter, a hint of the nearly sweet smell of horses. A Mexican guy opened the door. He was medium-sized and agile-looking with shoulderlength hair and a diamond stud in his ear. Behind him was another Mexican, bigger, bulkier, with a coat that fit too tight and a narrow tie that was knotted up tight to his thick neck.

Nobody said anything. The Indian turned and walked back toward my car. The graceful Mexican man nodded me into the house. Inside there was a large foyer with benches that looked like antique church pews on three walls. Three or four other Mexican men lounged on the benches. None of them looked like a poet. The slender Mexican made a gesture with his hands toward the wall, and I leaned against it while he patted me down. The bulky one stood and stared at me.

“Gun’s under the left arm,” I said.

Nobody said anything. The Mexican took my gun from my shoulder holster and handed it to the bulky guy. He stuck it in the side pocket of his plaid sport coat. The slender Mexican straightened and jerked his head for me to follow him. We went through an archway to the left and along a corridor that appeared to curve along the front of the house, like an enclosed veranda. We stopped at a door with a frosted glass window and the slender Mexican knocked and opened the door.

He nodded me through.

“Cat got your tongue?” I said He ignored me and came in the door. Through the frosted glass I could see the shadow of the bulky Mexican as he leaned against the wall outside.

Behind a bare wooden desk a man said, “What about Zabriskie?”

He looked like a stage Mexican. He had a thin droopy mustache and thick black hair that seemed uncombed and fell artfully over his forehead. He was wearing a Western-cut white shirt with billowy sleeves, and he was smoking a thin black cigar.

“You del Rio?” I said.

Behind the stage Mexican there was a low table as plain as the desk. On it was a picture of an aristocratic-looking woman with black hair touched with gray, and beside it, a picture of a young woman perhaps twenty, with olive skin and a strong resemblance to Jill Joyce. I was pretty sure I had a picture of her when she was younger, inside my coat pocket.

“I asked you a question, gringo.”

“Ai chihuahua!” I said.

Del Rio smiled suddenly, his teeth very white under the silly mustache.

“Then Chollo here sings a couple of choruses of ‘South of the Border,’ ” he said, “and we all have tortillas and drink some tequila. Si?”

“You got a guitar?” I said.

“The ‘gringo’ stuff impresses a lot of anglos,” del Rio said. “Makes them think I’m very bad.”

“Scared the hell out of me,” I said.

“I can see that,” del Rio said.

Chollo had gone to one side of the office and lounged in a green leather armchair, almost boneless in his relaxed slouch. His black eyes had no meaning in them.

“You see how we scared him, Chollo?” del Rio said.

“I could improve on it, Vic, if you want.” It was the first time he’d spoken. Neither he nor del Rio had even a hint of an accent.

“You sure you guys are Mexican?” I said.

“Straight from Montezuma,” del Rio said. “Me and Chollo both. Pure blood line. What’s this about Zabriskie?”

I took the picture out of my inside pocket and put it in front of del Rio. He looked at it without touching it. I picked it up again and put it back in pocket.

“So?” del Rio said.

“Your daughter,” I said.

Del Rio didn’t speak.

“I got it from her grandmother.”

Del Rio waited.

“Anything you don’t want him to know?” I said.

“Chollo knows what I know,” del Rio said. “Chollo’s family.”

“How nice for Chollo,” I said. “I know who your daughter’s mother is.”

“Yes?”

“Jill Joyce,” I said, “America’s cutie.”

“She tell you that?” del Rio said.

“No,” I said. “She hasn’t told me anything, and half of that is lies.”

Del Rio nodded.

“That would be Jill,” he said. “What do you want?”

“Information,” I said. “It’s like huevos rancheros to a detective.”

“Si,” del Rio said.

“Were you and Jill married?” I said.

Del Rio leaned back a little in his chair with his hands resting quietly on the bare desk top in front of him. His nails were manicured. I waited.

“Your name is Spenser,” he said. I nodded.

“Okay, Spenser. You think you’re a tough guy. I can tell. I see a lot of people who think they are a tough guy. You probably are a tough guy. You got the build for it. But if I just nod at Chollo you are a dead guy. You understand? Just nod, and…” He made an out sign, jerking his left thumb toward his shoulder.

“Yikes,” I said.

“So you know,” del Rio said, “you’re on real shaky ground here.”

“It goes no further than me,” I said.

“Maybe it doesn’t go that far,” del Rio said. “Why are you nosing around in my life in the first place?”

“I’m working on a murder in Boston,” I said. “And I’m working on protecting Jill Joyce. The two things seem to be connected and your name popped up.”

“Long way from Boston,” del Rio said.

“Not my fault. Somebody has been threatening Jill Joyce. Someone killed her stunt double. Jill won’t tell me anything about herself, so I started looking and I found her mother and then I found you.”

Del Rio looked at me again in silence.

“Okay, Spenser. I met Jill Joyce when she was Jillian Zabriskie and she was trying to be an actress, and I was starting to build my career. We were together awhile. She got pregnant. I had a wife. She didn’t want the kid, but she figured it would give her a hold on me. Even then I had a little clout. So she had it and left it with her mother. I got her some parts. She slept with some producers. I supported the kid.”

“You still got the same wife?”

“Yes. Couple years after Amanda was born, Jill’s mother started disappearing into the sauce. She was never much, but…” He shrugged. The shrug was eloquent. It was the first genuine Latin gesture I’d seen. “So my wife and I adopted her.”

“Your wife know about you and Jill?”

“No.”

“She know you’re the kid’s father?”

“No. She thinks we adopted her from an orphanage. We don’t have any other children.”

“How old is Amanda now?”

“Twenty.”

“What happens if your wife finds out?”

“Whoever told her dies.”

“What happens to her?”

Again the eloquent shrug. “My wife is Catholic,” del Rio said. “She is a lady. She would feel humiliated and betrayed. I won’t let that happen.”

“Amanda know?”

“No.”

We all were silent then, while we thought about these things.

“And Jill knows better than to talk about this,” I said.

“Jill don’t want to talk about it. Jill don’t want anyone to know she got a spic baby.”

“But if someone was looking into things you might want to squelch that,” I said.

“I wanted to, I would,” del Rio said.

“What if you sent some soldier out there to clip her and he got the wrong one,” I said.

“Get you killed,” del Rio said, “thinking things like that.”

I nodded. “Something will, sooner or later,” I said.

“Most people prefer later,” del Rio said.