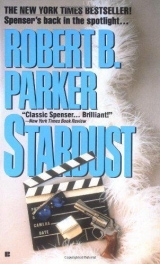

Текст книги "Stardust"

Автор книги: Robert B. Parker

Жанр:

Крутой детектив

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

Chapter 32

SUSAN had on glistening spandex tights and a green shiny leotard top and a white headband and white Avia workout shoes and she was charging up the stair climber like Teddy Roosevelt. I had on a white shirt and a leather jacket and I was leaning against one of the Kaiser Cam weight machines in her club watching her. When she exercised Susan didn’t glow delicately. She sweated like a horse, and as she thundered up the Stair Master she blotted her face with a hand towel. I was admiring Susan’s gluteus maximi as she climbed. She saw me in the mirror and said, “Are you staring at my butt?”

“Yes,” I said.

“What do you think?” she said. I knew she was making a large effort to speak normally and not puff. She was a proud woman.

“I think it’s the stuff dreams are made of, blue eyes.”

“My eyes are black,” Susan said.

“I know, but I can’t do a good Bogart on ‘black eyes.’ ”

“Some would say that was true of any color eyes,” Susan said.

“Some have no ear,” I said.

Susan was too out of wind to speak more, a fact which she concealed by shaking her head aniti.st-dly and pretending to concentrate harder on the stairs.“You still working on the glutes?” I said.

“Un huh.”

“No need,” I said. “They get any better you’ll have to have them licensed.”

“You are just trying to get me to admit I can’t talk and exercise,” Susan said. “Go downstairs.”

“You know the only other times I see you sweat like this?” I said.

“Yes,” she said. “Go downstairs.”

“Sure,” I said.

An hour and a half later Susan was wearing a vibrant blue blouse and a black skirt and we were sitting across from each other at a table in Toscano Restaurant eating tortellini and drinking some white wine, for lunch.

“Did you hear anything from the police?” Susan said. “About Jill?”

“No,” I said. “Not about Jill.”

I broke off a piece of bread and ate it. “Wilfred Pomeroy killed himself.”

“The one Jill was married to?”

“Yeah. Came down to Boston, left a note for me, and drove off a pier.”

“Why?”

“Press got hold of his story,” I said. “He couldn’t stand it, I guess. As if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen.”

“Maybe,” she said. “And maybe it was his chance to make the beau geste, to die for her, rather than let his life be used against her.”

“And a chance to say, simultaneously, See how I loved you, see what you missed, see what you made me do. ”

“Suicide is often, see what you made me do,” Susan said. “It is often anger coupled with despair.” I nodded. Susan nibbled on one of the tortellini. She was the only person I knew who could eat one tortellini in several bites.

“Is tortellini better than sex?” she said.

“Not in your case,” I said. “If you eat only one at a time of tortellini, are you eating a tortellenum?”

“You’ll have to ask an Italian,” Susan said. “I can barely conjugate goyim.”

We were quiet for a time. Concentrating on the food, sipping our wine. As always when I was with her, I could feel her across the table, the way one can feel heat, a tangible connection, silent, invisible, and realer than the pasta.

“Poor man,” Susan said.

“Yeah.”

“Will you find her, you think?”

“Yeah,” I said.

Susan smiled at me and the heat thickened. “Yes,” she said, and leaned across the table and put her hand on top of mine, “you will.”

Chapter 33

AFTER lunch I dropped Susan at Harvard, where she taught a once-a-week seminar on analytic psychotherapy.

“You’re going to stumble into the classroom reeking of white wine?” I said.

“I’ll buy some Sen-Sen,” Susan said.

“You consumed nearly an ounce,” I said, “straight.”

“A slave to Bacchus,” she said. “Drive carefully.”

She got out and I watched her walk away, until she was out of sight.

“Hot damn,” I said aloud, and pulled out into traffic.

I went through Harvard Square and down to the river, and across and onto the Mass. Pike. In about an hour and forty-five minutes I was in Waymark again. It took me a couple of tries but I found the road leading into Pomeroy’s cabin. There had been snow here, that we hadn’t gotten in eastern Mass., and I had to shift into four-wheel drive to get the Cherokee down the rutted road.

The cabin door was locked when I got there, and inside I heard the dogs bark. I knocked just to be proper and when no one answered but the dogs I backed off and kicked the door in. The dogs barked hysterically as the door splintered in, and then came boiling out past me into the yard. They stopped barking and began circling hurriedly until they each found the proper spot and relieved themselves, a lot. Inside the cabin there was a bowl on the floor half full of water, and another, larger bowl that was empty. I found a 25-pound sack of dry dog food and poured some into the bowl and took the rest out and put it in the back of the Cherokee. Finished with their business, the dogs hurried indoors and gathered at the food bowl. They went in sequence, one after another until all three were eating at once. While they ate I found some clothesline in the cabin and fashioned three leashes. When they were done I looped my leashes around their necks and took them to the car. They didn’t leap in easily, like the dogs in station wagon commercials. They had to be boosted, one after the other, into the back seat. Once they were in I unlooped the rope and dropped it on the floor of the back seat, closed the back door, got in front and pulled out of there.

On the paved and plowed highway I shifted out of four-wheel drive and cruised down to police headquarters. The patrol car was parked outside. It looked like a cop car designed by Mr. Blackwell. I left the dogs in the Cherokee and went on in to see Phillips.

He was behind his desk, his cowboy boots up on the desk top, reading a copy of Soldier of Fortune. He looked up when I came in, and it took him a minute to place me.

“You went out and hassled him, didn’t you?” I said.

Phillips was frowning, trying to remember who I was.

“Huh?” he said.

“Pomeroy. When I left you went back out there and made him tell you everything he told me, and then you couldn’t keep it to yourself, you went to the Argus and blatted out everything you knew; and got your picture taken and your name spelled right, and ruined what was left of the poor bastard’s life.”

Phillips had figured out who I was, but he kept frowning.

“Hey, I got a right to conduct my own investigation,” he said. “I’m the fucking law out here, remember?”

“Law, shit,” I said. “You’re a fat loudmouth in a jerkwater town playacting Wyatt Earp. And you cost an innocent man his life.”

“You can’t talk to me that way. Whose life?”

“Pomeroy killed himself this morning, in Boston. He had a copy of the Berkshire Argus story with him.”

“Guy was always a loser,” Phillips said.

“Guy loved too hard,” I said. “Too much. Not wisely. You understand anything like that?”

“I told you, you can’t come in here, talk to me like that, that tone of voice. I’ll throw your ass in jail.”

Phillips let his feet drop off the desk top and stood up. His hand was in the area of his holstered gun.

“You do that,” I said. “You throw my ass in jail, or go for the gun, or take a swing at me, anything you want.”

I had moved closer to him, almost without volition, as if he were gravitational.

“Do something,” I said. I could feel the tension across my back. “Go for the gun, take a swing, go for it.”

Phillips’ eyes rolled a little, side to side. There was a fine line of sweat on his upper lip. He looked at the phone. He looked at me. He looked past me at the door.

“Whyn’t you just get out of here and leave me alone,” he said. His voice was hoarse and shaky. “I didn’t do nothing wrong.”

We faced each other for another long, silent moment. I knew he wasn’t going to do anything.

“I didn’t do nothing wrong,” he said again.

I nodded and turned and walked out. And left the door open behind me. That’d fix him.

Chapter 34

“I KNOW people who might take one dog,” Susan I said. “But three? Mongrels?”

“I’m not breaking them up,” I said.

We were in my living room and the dogs were around looking at us. The alpha dog was curled in the green leather chair; the other two were on the couch.

“Where did they sleep last night?” Susan said. I shrugged.

Susan’s eyes brightened.

“They slept with you,” she said. I shrugged again.

“You and the three doggies all together in bed. Tell me at least they slept on top of the quilt.”

I shrugged.

“Hard as nails,” Susan said.

“Well,” I said. “I started them out in the kitchen, but then they started whimpering in the night…”

“Of course,” Susan said, “and they got in there and you sleep with the window open, and it was cold…”

“You’re the same way,” I said.

Susan laughed. “Yes,” she said. “I too think the bedroom’s too cold.”

“Dogs do not respect one’s sleeping space much,” I said.

“Did we sleep curled up on one small corner of the bed while the three pooches spread out luxuriously?” Susan said.

“I wanted them to feel at home,” I said.

“We must be very clear on one thing. When I visit, we are not sleeping with three dogs.”

“No,” I said.

“And when we make love we are not going to be watched by three dogs.”

“Of course not,” I said. “Hawk says he knows some woman owns a farm in Bridgewater and is an animal rights activist.”

“Don’t tell her about my fur coat,” Susan said.

“He thinks she’ll take them.”

Susan put the palm of her right hand flat on her chest and did a Jack E. Leonard impression. “I hope so,” she said, “for your sake.”

“You wouldn’t like to take them over to your place today,” I said. “I need to go to my office.”

“I have meetings all day,” she said. “It’s why I’m here for breakfast.”

“Oh yeah.”

“I’m sure they’ll love your office,” Susan said.

And they did, for brief stretches. Every hour or so they felt the need to be walked down to the Public Garden. In between walks they sat, usually in a semicircle, and looked at me expectantly, with their mouths open and their tongues hanging out. All day. Outside, Christmas was making its implacable approach. The dryness in the mouth of merchandising managers was intensifying, the exhaustion had become bone deep in the parents of small children, the television stations kept wishing me the best of the joyous season every station break, and the street gangs in Roxbury and Dorchester were shooting each other over insults to their manhood at the rate of about three a week. In the stores downtown people jostled each other; bundled uncomfortably in clothing against the cold, they were hot and angry in the crowded aisles where people sold silk show handkerchiefs and imported fragrances for the special person in your life. Liquor stores were doing a land-office business, and the courts were in double session trying to clear the calendar for the holiday break.

I got up and went to the old wood file cabinet behind the door and got out a bottle of Glenfiddich that Rachel Wallace had delivered to me last Christmas. It was still half full. I poured about two ounces in the water glass and went back to my desk. I sipped a little and let it vaporize in my mouth. Outside my window the dark winter afternoon had merged into the early darkness of a winter evening. I sipped another taste of the scotch. I raised my glass toward the dogs.

“Fa la la la la,” I said.

I could feel the single-malt scotch inch into my veins. I sipped another sip. In my desk was a letter from Paul Giacomin in Aix-en-Provence in France. I took it out and read it again. Then I put it back into the envelope and put the envelope back in my desk drawer. I swiveled my chair so I could put my feet on the window sill and gaze out at the unoccupied air space where Linda Thomas had once worked. Beyond it was a building that looked like an old Philco radio. A Philip Johnson building, they said. I raised my glass to it.

“Way to go, Phil,” I said. Lucky I hadn’t been assigned to guard it. Probably lose it. Was right here when I left it. My glass was empty. I got up and got the bottle and poured another drink and went back and sat and stared out the dark window. The dogs stood when I stood, sat back down when I did.

The light fused up from the street the way it does in a city and softened into a pinkish glow at the top of the darkened buildings. Maybe she was dead. Maybe she wasn’t. Maybe the pills and powders and booze and self-delusion and bullshit had busted her, and she had simply run and was running now.

I looked at the pinkish glow some more. I had nowhere I needed to be, nothing I needed to do. Susan was shopping. What if Jill had gone home? To her mother. To the hovel in the middle of the putrid hot field in the back alley of Esmeralda. I called Lipsky. “Maybe she went to her mother’s,” I said.

“Esmeralda police checked,” Lipsky said. “No sign of her. Just the old lady, or what’s left of her.”

“You thought of it,” I said.

“Honest to God,” Lipsky said and hung up.

I drank a little more scotch. I had a feeling I might drink a lot more scotch. One of the dogs got up and went to the corner and drank from the bowl pf water I’d put down. He came back with water dripping from his muzzle and sat and resumed staring.

The phone rang. When I answered an accentless voice at the other end said, “This is Victor del Rio.”

“Hey,” I said. “Que pasa?”

“She is here,” del Rio said.

“In L.A.?” I said.

“Here, with me,” del Rio said. “I think you better come out and get her.”

Chapter 35

I HAD my ticket. I was packed: clean shirt, extra I blackjack. And I was having breakfast with Hawk and Susan, in the public atrium of the Charles Square complex in Cambridge.

“Jewish American Princesses,” Susan was saying, “particularly those with advanced academic degrees, do not baby-sit dogs.”

I looked at Hawk.

“That is even more true,” he said, “of African American Princes.”

The three mongrels, tethered by clothesline, sat in their pre-ordered circle, tongues lolling, eyes fixed on each morsel of croissant as it made its trip from paper plate to palate.

“Can you imagine them tearing around my place,” Susan said, “with all the geegaws and froufrous I have in there, getting hair, yuk, on my white rug?”

I was silent, drinking my coffee carefully from the large paper cup, holding it in both hands. Hawk broke off a piece of croissant, divided it into three morsels and gave one each to the dogs. They took it delicately, in each case, from his fingers and stayed in place, eyes alert, after a quick swallow, and a fast muzzle lick, tongues once again lolling.

“Put ‘em in a kennel,” Hawk said. “Till my friend in Bridgewater gets back.”

I looked at the three dogs. They gazed back at us, their eyes hazel with big dark pupils and full of more meaning than there probably was. They wern’t young dogs, and there was a stillness in them, perhaps of change and strangeness, that had been in place since I got them.

“I don’t think they should go in a kennel,” Susan said. “They’ve had some pretty bad disruptions in the last few days already.”

Hawk shrugged. He looked at the dogs again. “Huey, Dewey, and Louie,” he said.

We all sat in silence, drinking coffee, eating our croissants. A blond woman wearing exercise clothes under a fur coat passed us, carrying a tray with two muffins on it. The dogs all craned their heads over nearly backwards sniffing the muffins as they went by, and when the scent moved out of range they returned their stare to us.

“Well,” Susan said, “I could come over to your place and stay with them at night. But during the day, I have patients.”

I nodded. We both looked at Hawk. Hawk looked at the dogs.

They stared back at him.

“What happens during the day?” Hawk said.

“They need to be walked.”

“How often?”

“Three, four times,” I said.

“Every day?”

“Yuh.”

Hawk looked at me. He looked at Susan and then back at the dogs.

“Shit,” he said.

“That’s a part of it,” I said.

“I meant shit, as in oh shit!” Hawk said.

“You and Susan can work it out in detail between you,” I said. “My plane leaves in an hour.”

Hawk was looking at me with a gaze that one less optimistic than I might interpret as hatred. I patted the dogs. Susan stood and we hugged and I kissed her. Hawk was still gazing at me. I put my hand out, palm up. He slapped it lightly.

“Thanks, bro,” I said.

“Honkies suck,” he said.

I took a cab to the airport. The plane took off on time, and I flew high above the fruited plain for six hours, cheered by the image of Hawk walking the three dogs.

Chapter 36

DEL Rio had her in a hotel on Sunset in West Hollywood, a big one with a great view of the L.A. Basin. She was in one bedroom of a two-bedroom suite. The Indian in the Italian suit who had first taken me to see del Rio was in there, in the living room, reading the L.A. Times with his feet up on the coffee table. He had on a white cotton pullover today, and I could see the outline of a gun stuck in the waistband of his tight pocketless gray slacks. He glanced up once when Chollo brought me in, then went back to the paper.

“Vic in with her?” Chollo said.

The Indian nodded. Chollo nodded at one of the chairs.

“Sit,” he said.

I sat. The room was large and square with the wall of picture windows facing south and the brownish haze above the basin, slightly below eye level, stretching to some higher ground in the distant south. To the left I could see the black towers of downtown poking up above the smog and to the right the coastline, fusing with the smog line in a sort of indiscriminate variation. The room itself was aggressively modern with bars of primary color painted on various portions of it and round-edged chrome structured furniture. The air conditioning was silent but effective. The room was nearly cold. Chollo leaned on the wall near one of the bedroom doors and gazed at nothing. His lips were pursed as if he were whistling silently to himself. His arms were folded comfortably across his chest. He was wearing a blue blazer over a white polo shirt. The collar of the shirt was turned up. I crossed one leg over the other and watched my toe bob. When I got bored I could cross my legs the other way.

I stared at the view.

After about ten minutes del Rio came out of the bedroom and closed the door behind him. He looked at me and nodded once. Then he looked at the Indian.

“Bobby, wait outside.”

The Indian got up, folded the newspaper over, and went out of the hotel suite. He closed the door behind him. Del Rio went to the bar in one corner of, the room. There were three stools at the bar. He sat on one of them. Chollo peeled off the wall and went past him and behind the bar. He mixed a tall scotch and soda, added ice, and handed it to del Rio. Del Rio looked at me and gestured with the glass.

“Sure,” I said. “Same thing. Lots of ice.”

Chollo made me a drink, and then poured out a short one and tossed it off himself, put the glass back on the bar, leaned back against the mirrored wall behind the bar, and waited. Del Rio sampled his drink, smiled.

“It’s blended,” he said.

“Want I should call down for a single malt?” Chollo said.

Del Rio shook his head. “Won’t be here that long, I hope.”

I tasted my drink. I couldn’t tell, not with the soda and ice. Del Rio took another sip.

“Nice to see you again, Spenser.”

“Sure,” I said. “When do I see Jill?”

“Pretty soon. I think we better talk first.”

I waited. Chollo refolded his arms behind the bar and his gaze fixed on something in the middle distance. Del Rio was in black today, a black silk suit, double breasted, with a white silk shirt, and a narrow black scarf at the open neck. He wore black cowboy boots with silver inlays. Del Rio tasted his drink again.

“She showed up here yesterday morning in a state. Barely functional. She doesn’t know where I live, but she came to one of the, ah, offices I use in East L.A. and told the guy there that she had to see me.”

“Guy know who she was?” I said.

“Yes. But he is discreet. So he called the house and Bobby Horse went down and got her and brought her here. I keep a suite here, anyhow.”

“Of course,” I said. “Anyone would.”

“Chollo and I met her here, and she and I talked for a long while.”

“She offer to ball you?” I said.

“Of course,” del Rio said.

“And you declined,” I said.

“Perhaps that is not your business,” del Rio said.

“Perhaps you called me,” I said.

Del Rio nodded. “She said that I was the only one who could help her. That no one else would help her and that He was going to get her.

”I asked her who He was. She said she didn’t know. I asked her how she knew He was trying to get her. She said He’d called her again, the night she took off.“

”You know when that was?“

”Yes. It made the papers. Especially here,“ del Rio said. ”This is a company town.“ He sipped his scotch, looking at the glass. ”Times when there’s nothing better,“ he said. I nodded and rattled the ice around in my glass a little and took a small sip.

”I asked her what He said to her. She said He said awful things.“

”That’s our Jill,“ I said. ”Full of hard information.

“She said you wouldn’t protect her, that some guy named Hawk wouldn’t protect her, that the studio didn’t give a shit, and that I was all she had left. She said I had to help her.”

“What are you supposed to do?” I said.

“Make Him leave her alone.”

“But she doesn’t know who Him is.”

“This is true,” del Rio said.

“So what do you want me to do?” I said.

“Get her the fuck out of here,” del Rio said. “I don’t want her around.”

“Has she threatened to reveal all?” I said.

“She knows better,” del Rio said. “But she’s such a mess that I’m afraid she may cause trouble without meaning to, and I don’t want to have to dump her to prevent it.”

“What a softie,” I said.

“Don’t make that mistake,” del Rio said. “You want to talk with her?”

“In a minute,” I said. “What do you think?”

“About her?”

“Yeah.”

“I think she needs a shrink.”

I nodded. “How about the mysterious He?”

“I think it’s in her head,” del Rio said.

“Who killed Babe Loftus?” I said.

Del Rio shrugged, turned his palms up. “Hey, I’m a simple Mexican,” he said. “That’s your line of work.”

“And I’m doing it grand,” I said.

“Grand,” del Rio said.

“What about the harassment?” I said. “The hanged doll-that stuff?”

“I think she did it herself,” del Rio said. “She’s trying to get people’s attention.”

“It’s working,” I said.

A dark cloud had drifted up from the basin and some big raindrops splattered occasionally on the picture window. We all sat in silence.

“She drinking?” I said.

“If she cut back, she’d be drinking,” del Rio said. “You want a refill?”

I shook my head.

“Let’s talk with her,” I said.

Del Rio nodded, and Chollo went around the bar and opened the door to the bedroom. He said something I couldn’t hear and, in a moment, Jill came out. You could see that she’d been crying. Her eyes were puffy. The eyeliner was gone, or most of it was. Her nose was red. Her hair was uncombed and looked as if she’d been running her fingers through it. She was soused to the lip line and it showed in the unsteadiness of her walk.

“Well, damn,” she said when she saw me. “The big dick from Boston.” She went to the bar and put her glass out on it. Chollo went around without comment and fixed her a new drink, scotch, water, ice. She stopped his hand after he’d added only a splash of water.

“What you doing out here, Big Dick?”

Behind the bar Chollo had no expression. Del Rio put his hands behind his head and leaned back in his chair as if to give me my turn, see what I could do.

“Why’d you run off?” I said.

“He called.”

“The night you left?”

“Yes.”

“And you don’t know who he is?”

“No.”

“What’d he say?” She shook her head.

“Did he threaten you?” She nodded.

“What did he threaten you with?” She shook her head again.

“Why won’t you say?”

She drank most of her drink before she answered. “Don’t be so fucking nosy,” she said.

“How in hell am I going to help you if I don’t know what I’m trying to help you with?”

“Maybe if you’d get off your ass and catch him,” she said, “and put him away where he belongs… that might help, you know?”

She finished her drink, held the glass out, and Chollo replenished it. Del Rio’s dark compassionless eyes watched her carefully.

“Anything else happen that night?” I said. She shrugged.

“Hawk make a pass at you?”

“How’d you know?” she said. She got a crafty look on her face.

“He said there was some talk of, ah, hanky-panky, but it didn’t, if you’ll pardon the expression, come to anything.”

“You bet your ass,” she said. “I’m not fucking some coon.”

“So you turned him down,” I said.

“Sure, limp dick motherfucker. He’s a tighter ass than you.”

“And that’s why you turned him down.”

“You bet your buns. Lotta men give up a year of their life to fuck me. But you goddamned pansies.” She tossed her chin at del Rio. “Him too.”

“Yes,” I said. “I understand you brushed him off tonight too.”

She nodded righteously and drank more scotch. “When He called, the bad guy, the man who threatened you, how did he get through?” I said.

“Huh?”

“How did he reach you?”

“He just called up,” she said. “I answered the phone.”

“This was after Hawk left you,” I said. “After eleven?”

“Sure.”

“Are you telling me that anyone, without even giving a name, could call up the Charles Hotel at, say, eleven-thirty at night and be put right through to your room, no questions asked?”

The crafty look got a little fogged over; her brows furrowed. She wasn’t a deep thinker sober, and she was a long distance past sober. She opened her mouth once, and closed it again. She looked at del Rio. She drank some scotch. I waited.

“Leave me alone,” she said.

“Jill,” I said, “the only way anyone can call your room is to be on a call list, and identify themselves. You know that. I know that. I’m on the list. Otherwise half the city of Boston would call you up every day. You’re a star.”

“You’re goddamned right,I am,” Jill said. “And you better, goddamn it, start treating me like one.”

Her breath seemed short. Her face was reddening “Somebody better,” she said.

She let her head drop and took hold of her drink with both hands and then her shoulders sagged forward.

“Somebody better,” she said again and started to cry. The crying was hysterical and had the promise of duration. I looked at del Rio. He looked at me. Chollo looked at whatever he looked at. We waited. After a while she stopped sobbing long enough to get a cigarette going and sip some scotch.

“Why won’t anyone take care of me,” she said in a gasping voice and started to cry again. Through the picture window I could see that the dark cloud had moved directly over us. The occasional raindrops that had spattered on the window intensified. They came now in a steady rattle.

Del Rio said, “Would you like to see your mother, Jill?” There was no kindness in his voice, but no cruelty either.

“God, no,” Jill said, still crying, her face buried in her hands, the cigarette drifting smoke from her right hand.

“Maybe your father,” I said. “Would you like to talk with your father?”

She sat suddenly upright. “My father’s dead,” she said and continued to cry, sitting up, facing us, occasionally swigging in a gulp of scotch or dragging in a lungful of smoke, between sobs. I turned that over in my mind a little.

“Your father’s not dead, Jill. He’s here in Los Angeles.”

“He’s dead,” she said.

“I’ve talked with him,” I said. “Only a week or so ago.”

“He’s dead,” she screamed at me. “Goddamn it, my father is dead. He died when I was little and he left me with my mother.”

She drank off the rest of her drink as the echoes of her scream were rattling around the hotel room, and then she pitched suddenly forward and passed out, facedown on the floor. I reached down and took the burning cigarette from her hand and put it out in an ashtray. Chollo came around the bar, and he and I picked her up and carried her into the bedroom. We put her on her back, on her bed. I put the spread over her and we left her there and carne back out into the living room.

“Lushes,” Chollo said. “Lushes are crazy.”

Del Rio was where we had left him, sitting still with his hands clasped behind his head.

“Know anything about her father?” I said.

“She told me he left when she was a kid. Coulda meant he died. I took it to mean he just left,” del Rio said. “Who’s this guy you talked to?”

“Guy named Bill Zabriskie, her agent put me onto him.”

“She sure threw a wingding when you said he was alive,” del Rio said.

“Yeah,” I said. “You got someone to run an errand?”

Del Rio nodded. “Chollo,” he said, “tell Bobby Horse to come here.”