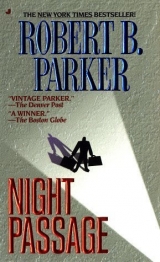

Текст книги "Night passage"

Автор книги: Robert B. Parker

Жанр:

Крутой детектив

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter 68

Hasty didn’t like driving in city traffic. But he had to see Gino Fish, so the big Mercedes was wedged into the northbound commuter traffic on the Southeast Expressway. Hasty was nearly in tears.

“You dumb bastard,” he said to Jo Jo.

“What the hell are you yelling at me for?”

“Because this was your deal. You were the one vouched for Fish.”

“Bullshit,” Jo Jo said. “You come to me, I was trying to do you a favor. Don’t whine to me it didn’t work out.”

“You bastard,” Hasty said.

He turned off at Mass. Avenue and drove past Boston City Hospital. He didn’t like the city, and didn’t spend much time there. It took him two or three false turns to find Tremont Street and another ten minutes to find the block where Gino Fish had his storefront.

“You needa be careful about this,” Jo Jo said. “That Vinnie Morris is a quick sonova bitch.”

“I thought you were a tough guy,” Hasty said. “Are you scared of these people?”

“No, but it don’t make no sense,” Jo Jo said, “go charging fucking in there? Yelling and waving your arms, you know?”

“The goddamned fairy took my money,” Hasty said. “The Horsemen’s money. If I have to I’ll bring the whole militia company in here. And I’m going to tell him that.”

Hasty parked beside a hydrant near the Cyclorama, and got out.

“You going to back me?” he said to Jo Jo.

“I didn’t cut in for that,” Jo Jo said. “I set up the deal. They welshed on it. It’s between you and them.”

“You yellow belly,” Hasty said.

He slammed the door, and turned and went down Tremont Street to the storefront. It was empty. The door was locked. Hasty groaned in anger and disappointment and turned and went back to his car. He got in and started up without a word.

“Nobody there?” Jo Jo said.

Hasty nodded as he yanked the Mercedes out into the traffic and drove out of the South End on Tremont Street.

“I knew there wouldn’t be,” Jo Jo said. “Why I didn’t waste time walking down there.”

“You’re a yellow belly,” Hasty said.

“You want to go one on one with me?” Jo Jo said.

“These are your people, Jo Jo. I want my weapons, or I want my money.”

“You been stiffed, asshole. Don’t you get it? There aren’t any fucking weapons.” Jo Jo said “weapons” in exaggerated scorn. “There never were any weapons. They saw you coming.”

“You brought me to them. You get the money back.”

Jo Jo shook his head.

“I mean it, Jo Jo. You are in this far too deeply to just walk away.”

Jo Jo felt a little tingle of fear race up the backs of his thighs. His glance shifted onto Hasty’s face, and held. He pulled his chin down into his neck almost like a turtle retracting, and his neck thickened.

“I may be in it, Hasty, but I sure as shit ain’t in it alone.”

Hasty didn’t answer right away. He had driven out of the South End and onto Charles Street where it ran between the Common and the Public Garden. The city rose up all around them. A cold rain had begun to spit and Hasty turned the windshield wipers on to low intermittent.

“I do not believe what I am hearing,” Hasty said finally.

He was choosing his words carefully, talking as if to an adolescent, trying to speak with the icy assurance of command.

“We have paid you well for work you were willing to do. Now you speak as if, somehow, that gave you knowledge which you would use against us.”

“Hey, you’re the one talking about getting in deep,” Jo Jo said.

“And you are in deep. There is no information you have which you could use against us that would not also incriminate you.”

“You want people to know about Tammy Portugal? Or how you had me throw Lou Burke off the rocks? You think that might not get you in just a little fucking trouble?”

Hasty shook his head as if saddened. He turned left onto Beacon Street, past the Hampshire House with its line of tourists outside the Cheers bar.

“Jo Jo, you haven’t the intestinal fortitude. You inform on me and you go to the electric chair. It’s as simple as that, and you know it. You have great big muscles, and you are mean as hell, but you are as yellow as they come. You have nothing on me that won’t get you in trouble too.”

Jo Jo stared at Hasty with eyes that seemed without pupils, opaque eyes too small for his crude face. As Hasty watched him, between glances at the road, Jo Jo’s color deepened, and a small muscle twitched in his cheek.

“I oughta just throw you off the fucking rocks,” Jo Jo said.

“My men would tear you apart if that happened,” Hasty said. “Don’t threaten me, Jo Jo. I’m not afraid of you.”

“You think I’m bluffing?”

“I think you better think about how to get the money back that you allowed us to be cheated out of,” Hasty said.

At Berkeley Street he turned the car onto Storrow Drive and they headed back to Paradise in utter silence.

Chapter 69

Jesse stood alone in Lou Burke’s small garden apartment. What struck him most was the anonymity of it. No pictures of family. No books. No old baseball gloves with the infield dust ground into the seams. Jesse walked slowly through the three small rooms. No newspapers stacked up. No magazines. A television set with a twenty-six-inch screen glowered at the living/dining area off the kitchenette. A small desk near the entry. Some bills due the end of the month. Two canisters of coffee on the kitchen counter, a Mr. Coffee machine. Some milk and some orange juice in the refrigerator. A couple of pairs of slacks in the closet, a blue suit, a starched fatigue outfit with Freedom’s Horsemen markings. Clean police uniform shirts in the bureau drawer. An alarm clock on the bedside table. No fishing equipment. No hunting gear. No cameras. No binoculars. No rugs on the floor. No curtains on the windows. The shades were all drawn to precisely the middle of the lower window. The bed was tightly made. There was no dust. No plants. No bowling trophies. The floors were polished. In the front hall closet was an upright vacuum cleaner.

Not much of a life, Lou.

Jesse stood in the middle of the living room and listened to the silence. He turned slowly. There was nothing he was forgetting. Nothing he’d overlooked. He wondered if his apartment would look like this to a stranger, empty and lifeless and temporary. He was glad Jenn’s picture was on his bureau. He looked once more around the small empty space. There was nothing more to see. So Jesse went out the front door and locked it behind him.

Back at the station Jesse stopped to talk with Molly.

“We got a typewriter around here anywhere?” Jesse said.

“Nope. Got rid of them five years ago when we got the computers.”

“Don’t have one left over in the cellar or the storage closet in the squad room, or anyplace?”

“No. Tom made a deal with a used-typewriter guy, from Lynn. When we went computer the typewriter guy came in, took all three typewriters. You want me to see if I can get you one?”

Jesse shook his head.

“No, just curious. Lou Burke have any family?”

“None that I know, Jesse. Parents died a while back. Far as I know he never married.”

“Brothers? Sisters?”

“Not that he ever talked about. Pretty much the department and the town was what he had.”

Jesse didn’t miss the cutting edge in the remark. The department was Lou Burke’s life, and Jesse had taken it from him.

“There was no typewriter in his apartment,” Jesse said.

“I’m sure there wasn’t,” Molly said. “Lou was a wonderful cop but he hated to write anything. I used to do half his reports for him.”

“So where did he type out his suicide note?” Jesse said.

Molly looked up at Jesse and started to speak and stopped and frowned.

“There’s no typewriter at his house,” she said.

“That’s correct,” Jesse said.

“The note wasn’t printed out of a computer.”

“No,” Jesse said.

“Maybe he went to somebody’s house that had a typewriter,” Molly said.

Jesse picked up a pad of blue-lined yellow paper from Molly’s desk. There were fifty pads just like it in the office supply cabinet in the squad room.

“Wouldn’t it have been easier to have handwritten the note?” Jesse said.

“That is odd,” Molly said. “Though suicidal people are, you know”—Molly tossed her hands—“crazy.”

Jesse put the notepad back down on Molly’s desk. He didn’t say anything.

“Unless he didn’t write the note,” Molly said. “And whoever did it just assumed that there’d be typewriters in the station. But even if there were, we’d find out pretty quick that they weren’t used for the note.”

“Which means whoever wrote it was stupid,” Jesse said.

“That’s not all it means,” Molly said.

“No,” Jesse said, “it’s not.”

He walked back toward his office. Molly watched him as he went.

“Jesus,” she said softly.

Chapter 70

Jesse parked his car in the curving cobblestone driveway of the Episcopal church rectory. It was a big brick building with a green center entrance door and green shutters. It was a bright morning, and the grass of the rectory lawn was wet with the early morning frost that had melted in the sun. A woman wearing an apron over a flowered dress answered Jesse’s ring.

She said, “Reverend is expecting you, Chief Stone.”

Jesse followed her into the study, where the reverend was at his desk. The room was lined with books, and there was a fire burning in the fireplace. Reverend Cotter was gray-haired and pink-cheeked. He was wearing a brown tweed jacket over his black minister’s front-and-backward collar. He stood and shook Jesse’s hand and gestured him to a chair beside the desk. He waited until the housekeeper had left before he spoke.

“Thank you very much for coming so promptly,” he said.

He had a deep voice, and he was pleased with it.

“Glad to,” Jesse said.

Cotter unlocked the middle drawer of his desk with a small key on his key chain, and tucked the key chain back into his pants pocket. He opened the drawer and took out a five-by-seven manila envelope and placed it on his desk, taking time to center it and to adjust it so that it was neatly square in the middle of his clean desk blotter.

“This is very embarrassing,” he said.

“Whatever it is,” Jesse said, “it won’t be as embarrassing as other stuff I’ve been told.”

Cotter nodded.

“Yes, I’m sure. Indeed I often reassure my own parishioners in the same way when they come for help.”

Jesse nodded and smiled politely. Cotter took in a big breath of air and let it out. Then he handed the envelope to Jesse. It was postmarked the previous day from Paradise. It was addressed to Reverend Cotter, probably with a ballpoint pen, in block printing, no return address. Inside was a Polaroid picture. Jesse took it out, handling it by the edges, and looked at it. It was a picture of Cissy Hathaway, naked and provocative on a bed. There was nothing else in the envelope except a piece of shirt cardboard used to protect the picture. There was nothing in the picture to identify the room.

“Just this?” Jesse said.

“Yes,” Cotter said.

“Any idea why this would be sent to you?”

“No.”

“It came this morning?”

“Yes.”

Jesse sat quietly looking at the picture. He could see no real expression in Cissy’s face, though the harsh light of the Polaroid flashbulb would wash out subtlety.

“Mind if I keep this?” Jesse said.

“Please,” Cotter said. “I certainly don’t want it.”

“Anything else arrives let me know,” Jesse said. “Or if anything occurs to you.”

“Of course,” Cotter said.

Jesse put the picture back in the envelope, and slid the envelope in the side pocket of his jacket.

“What are you going to do?”

“We’ll check it for fingerprints,” Jesse said.

“Are you going to speak to Cissy?”

“Yes,” Jesse said.

“I . . . I am her minister,” Cotter said. “If I can help . . .”

“Sure,” Jesse said. “I’ll let you know if we need you.”

Chapter 71

Jesse sat with Cissy Hathaway in her kitchen, looking out at the backyard now flowerless, the grass yellow in the weak sunlight. He handed her the Polaroid.

“This came today in the mail addressed to Reverend Cotter,” Jesse said.

Cissy took the picture and stared at it. As she looked at the picture she began to blush. Jesse was still. Cissy kept her eyes fixed on the picture, her face expressionless except for the bright flush that made her look feverish. She didn’t say anything, and Jesse didn’t say anything, and the silence grew stifling the longer it went on.

Finally Jesse said, “As far as I can see, there’s no crime here. You can tell me to buzz off, if you want to. But I thought you should know.”

Cissy put the picture facedown on the kitchen table and stared at the blank back of it. Jesse waited. Cissy got up from the table suddenly and walked to the counter. She got a pack of cigarettes, lit one, and stood with her back to him looking out the window over the sink at her driveway and the neighbor’s yard beyond it. She took a deep inhale and let the smoke dribble out. Jesse was silent.

“Jo Jo,” she said with her back still to him. “Jo Jo Genest took that picture. He has others.”

“Did he coerce you?” Jesse said.

“No.”

“Do you know why he sent the picture to your minister?”

Cissy took another big inhale and let the smoke out, still with her back to Jesse. She seemed to be memorizing every detail of the neighbor’s lawn. Jesse was quiet. It was going to come, he knew that. All he needed to do was wait.

“Yes,” Cissy said. “I know.”

“Can you tell me?” Jesse said.

Cissy took a last drag on her cigarette and dropped it into the sink, turned on the water, flicked the disposal switch, and watched the butt disappear. Then she shut off the disposal, turned off the water, and turned from the sink. The high color had left her face. Her eyes seemed larger than Jesse remembered.

“I am going to have to tell you things that mortify me,” she said. “I will. But you have to promise not to be judgmental.”

“I won’t be judgmental, Cissy.”

“No, I think you won’t. It’s why I think I can tell you.”

Jesse nodded gently and waited. Cissy stood at the sink and folded her arms.

“You have to help me, Jesse,” she said. “You have to help me say these things.”

Jesse stood and walked over to the sink and put one arm around Cissy’s shoulders. She stiffened but she didn’t move.

“I was a cop,” Jesse said, “in the second-largest city in the country. I have heard stuff you can’t even imagine. I have seen stuff you don’t even know exists.”

She nodded slowly, her arms still folded, his arm still around her shoulder.

“You’re human, Cissy. Humans do things that they’re ashamed of. They get in trouble. They need help. I don’t want to get too dramatic here, but that’s what I’m supposed to do. I’m supposed to help you when you get in trouble.”

Cissy nodded again. Then they were both quiet, Cissy hugging herself, Jesse’s arm around her shoulder.

“I have been married to Hasty for twenty-seven years,” Cissy said softly. “I don’t know if I love him, sometimes I don’t even know if I like him, but we’ve been together so long.”

She fumbled another cigarette out of the package and lit it.

“I think Hasty likes sex. I know I do. But somehow we don’t seem to like it with each other. When we have sex it’s . . . technically correct, I guess. But it is not much else and we don’t have it very often. I feel very stiff and cold and awkward having sex with Hasty.”

She smoked for a time, watching the exhaled smoke drift toward the ceiling.

“The longer we have been together, the odder Hasty has become. He was an important young man from a good family when I first met him. All this business with Freedom’s Horsemen . . .”

She shook her head.

“It occupies him more and more every year. I needed sex. And, I guess there is something very wrong with me, some of the kind of sex I needed.”

“No reason, right now, to decide if there’s something wrong with what you needed,” Jesse said.

“I know. I tell myself that. I took a series of lovers. Some of them were nice normal men who were happy to do nice normal things with me.”

She took in some smoke and blew it out.

“I actually met Jo Jo through Hasty. He came to the house one day. He and Hasty talked business in the den and I brought them some beer. The way Jo Jo looked at me. It was like he knew. I could feel his look go right through my clothes. Right through everything I pretended to be. I knew he saw me. And I let him know I knew.”

She was still standing stiffly, but she had allowed her head to rest lightly against Jesse’s shoulder.

“He wasn’t the first man, but he was the worst one,” Cissy said. “And the worse he was, the worse I was.”

She stopped talking and seemed to be thinking about her badness.

“The pictures?” Jesse said.

“They were my idea. I . . . liked being that way and I liked to see myself that way.”

“There are more pictures?”

“Many.”

“And he has them?”

“Yes.”

“Probably been better,” Jesse said, “if you kept them.”

“Maybe I half wanted him to tell,” she said.

“Maybe.”

She half turned and dropped her cigarette in the sink and repeated the process of washing it down the disposal. Then she settled back against Jesse’s shoulder.

“So why did he go public now?” Jesse said.

“I think he’s mad at Hasty,” she said.

“About what?”

“They had some kind of a business deal that went badly. Hasty blamed Jo Jo.”

“What kind of business deal?”

“I don’t know.”

Cissy turned in against Jesse and put her face into his chest. It was hard to hear her voice, muffled as it was against him. He could feel her trembling and he patted her shoulder a little. Over her shoulder he looked at his watch. Whatever was coming was coming slow. Finally she spoke again, her voice muffled against his chest.

“Jo Jo killed Tammy Portugal.”

There, Jesse thought. Cissy kept her face buried in his jacket. She was hanging on to him as if she might blow away if she let go.

“He used to tell me how he did it.”

“How he killed Tammy?”

“Yes.”

She began to sob against him. Big paroxysmal sobs, her body heaving. She said something he couldn’t understand.

“What did you say?”

She shook her head.

“No, you’ve come this far,” Jesse said, “and we’re still okay. You can say it. I can hear it.”

“I liked hearing about it,” she said, gasping the words out between sobs. “And he knew I wouldn’t tell anyone because then I’d have to tell how I knew.”

Jesse was silent for a moment, patting her shoulder gently. He had hold, finally, of the grotesque animal he’d been hunting. And he would have to pull it, snarling and vicious, slowly out of its hole. He didn’t know yet how big an animal it was going to be.

“I’m going to have to ask you to testify,” Jesse said.

She nodded her head against him, her body shaking. He held her. The sobbing went on for a long time. He patted her gently. He could hear the occasional car go ordinarily by on Main Street. Somewhere he could hear a dog bark.

“You were brave to tell me,” Jesse said.

She nodded against him.

“I had to tell you,” she said. “I couldn’t have those pictures all over town.”

“The next brave thing you are going to have to do is get psychiatric help. Good help. An honest-to-God shrink.”

“I’m sick,” she said into his chest, “I know I am.”

“You can get well,” Jesse said. “You know a shrink?”

She shook her head.

“Your family doctor can refer you,” Jesse said. “This is too hard to do alone. You need to save yourself.”

“My God,” she said. “Jo Jo will kill me.”

“Jo Jo will be in jail,” Jesse said.

Chapter 72

Jesse took Peter Perkins and Anthony DeAngelo with him to arrest Jo Jo. Both men carried shotguns. He didn’t know if he could trust them either, but it was time to find out. He didn’t want to have to kill Jo Jo; a show of force usually made an arrest go smoother. They waited in the parking lot in the back of the gym where Jo Jo trained and took him, shotguns leveled, without incident when he came out to his car. They brought him handcuffed to the station. Molly at the front desk watched in silence as they led him past her and locked him up in one of the holding cells in the back. DeAngelo and Perkins left. Jesse went back out front.

“I’ll cover the desk,” Jesse said to Molly. “You can go home.”

“You sure you don’t mind being alone with him?” Molly said.

“Be fine,” Jesse said and smiled at Molly. “Give us a chance to really get to know each other.”

“Won’t that be swell,” Molly said and got her things together and left. Jesse watched her go down the front steps of the station, then he went to his office, got a tape recorder, and walked slowly back to the cell area. He pulled up a folding chair, plugged in the tape recorder, and talked with Jo Jo through the bars.

“That thing on?” Jo Jo said.

“Not yet,” Jesse said.

He held the recorder so that Jo Jo could see that it wasn’t.

“Get used to the cell, Jo Jo,” Jesse said. “You’re going to be in one the rest of your life.”

“You can’t prove shit,” Jo Jo said.

“Jo Jo, you know you did her, and I know it, and we got a witness who’ll swear you bragged about it. We’re going over you and everything you own—your car, your house. We’re going to find forensic evidence, Jo Jo.”

“You been out to get me since you come to town,” Jo Jo said.

“When’s the last time you had sex with a woman?” Jesse said.

Jo Jo stared at him. “Why you want to know?”

“Because it’s the last time,” Jesse said.

Jo Jo continued to stare at him.

“Give you a chance to find out how tough you really are, though. Cons always like to test the bodybuilders, you know? See if they can back it up. Some guys at Cedar Junction be real proud to have Mr. Universe punking for them.”

Jo Jo had been sitting on his cot. He stood now and walked to the bars.

“What do you want, Stone?”

“I want to help you, Jo Jo. I want to find some sort of deal for you.”

“Like what?”

“Like maybe you shouldn’t have to go down alone for this. Maybe if we talked about what kind of business you are doing with Hasty Hathaway. Maybe you might be able to tell me something about Tom Carson’s death, or Lou Burke’s.”

“I don’t know nothing about that.”

“Too bad,” Jesse said.

Jo Jo walked to the back wall of the cell and turned and walked to the barred door again.

“What kind of deal?”

“Depends what I hear, and how good it is.”

Jo Jo walked to the back wall and turned and leaned on it, looking at Jesse.

“So I spill my guts to you and you don’t promise me nothing.”

Jesse smiled.

“Works for me,” he said.

“No deal,” Jo Jo said.

Jesse waited.

“You can’t even get me for Tammy, no way you can prove it.”

Jesse waited.

“If I did know something, I’m not going to fink out without something better than you’re offering.”

“You need a little time,” Jesse said, “run this thing over in your mind, think about how your life is going to go from now on. I’ll come back in a while and see you.”

“I got to know what the deal is,” Jo Jo said.

Jesse turned and left him there standing alone in the dim light at the back of his tiny cell, the tape recorder silently waiting on the floor by the folding chair outside the bars.

![Книга Legendary Moonlight Sculptor [Volume 1][Chapter 1-3] автора Nam Heesung](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-legendary-moonlight-sculptor-volume-1chapter-1-3-145409.jpg)