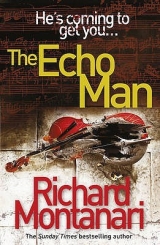

Текст книги "The Echo Man"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Chapter 68

When Byrne walked into the office he was more than a little surprised to see that, in addition to Sergeant Westbrook, there were Michael Drummond from the DA's office and Inspector Ted Mostow. In the corner, arms crossed, smug look in place, was Dennis Stansfield. Russell Diaz held down the other chair.

'Inspector,' Byrne said. 'Good to see you, sir.'

'How've you been, Kevin?'

'Better days.'

'How's the baby?'

Byrne shrugged, more or less on cue. 'Ten fingers, ten toes.'

It was an old expression, one that meant all was well with whatever case you were working on. In homicide you responded that way whether the case was going well or not.

Byrne nodded at Michael Drummond. 'Mike.' Drummond smiled, but there was no warmth in it. Something was wrong.

'Please, have a seat,' Westbrook said. Byrne took a chair near the windows.

'As you know, Detective Stansfield is working the Eduardo Robles homicide,' Drummond began.

Byrne just listened. Drummond continued.

'In the course of his investigation he discovered the existence of a surveillance camera on the opposite side of the street, just across

from the Chinese restaurant. After watching footage from the time frame in question, and running the plates on the six vehicles parked on the street, he contacted and interviewed the owners. All but one checked out, and had solid alibis for where they were that night at that time.'

Byrne said nothing.

'The sixth vehicle, a black Kia Sedona, belongs to a man named Patrick Connolly.' Drummond fixed him with a stare. 'Do you know a Patrick Connolly?'

Byrne knew that Drummond, along with everyone else in the room, knew the answer to that question, along with most of the questions he had not yet heard. Byrne had been on the other side of the table too many times not to know the game. 'Yes,' he said. 'He's my cousin.'

'When Detective Stansfield interviewed Mr. Connolly, Connolly told him that he had loaned the minivan out, that he had loaned the vehicle to you. Is that true?'

'Yes,' Byrne said. 'I borrowed the van six days ago.'

'Were you driving it the night in question?'

'I was.'

'Were you in Fishtown that night?'

Again, Byrne knew that everyone knew the answer to this question. No doubt they had spoken to patrons of The Well, people who had put him in the bar that night. 'Yes.'

'Do you recall seeing Mr. Robles that night?'

'Yes.'

'Did you have a conversation or interact in any way with Mr. Robles on that night?'

Byrne had begun to answer the question when Inspector Mostow interrupted. 'Kevin, do you want your PBA representative in here?'

The Police Benevolent Association provided legal advice and representation for police officers.

'Is this on the record?' Byrne knew the answer to that question – there was no court reporter, he had not been sworn in, and no one was writing anything down. He could confess to the Lindbergh kidnapping in this room, and it could not be used against him.

'No,' Drummond said.

Byrne looked over at Stansfield. He knew what the man was trying to do. This was payback. The two men locked eyes, matching wills. Stansfield looked away 'Then let's put it on the record,' Byrne said.

Drummond took a few seconds, looked at Inspector Mostow. Mostow nodded.

Drummond gathered a few papers, spirited them into his briefcase. 'Okay, we'll meet back here in the morning,' Drummond said. 'Eight o'clock sharp.'

Stansfield piped in. 'Inspector, I really think that we should–'

Mostow shot him a look. 'In the morning, detective,' he said. 'Are we clear?'

For a moment, Stansfield didn't answer. Then, 'Yes, sir.'

Byrne was out of Westbrook's office first. Every detective in the duty room had their eyes on him.

As Byrne crossed the room to get a cup of coffee, Stansfield followed him.

'Not so much fun, is it?' Stansfield said.

Byrne stopped, spun around. 'You don't want to talk to me right now.'

'Oh, now you don't want to talk? It seems you couldn't keep your mouth shut the past few days about me.' Stansfield got a little too close. 'What were you doing in Fishtown that night, detective?'

'Step away,' Byrne said.

'Doing a little cleanup work?'

'Last time. Step away.'

Stansfield put a hand on Byrne's arm. Byrne pivoted, lashed out with a perfectly leveraged left hook, his entire body behind it. It caught Stansfield square on the chin. The impact sounded like two rams butting heads, echoing off the walls of the duty room. Detective Dennis Stansfield spun in place, went down.

And out.

'Ah, fuck,' Byrne said.

The whole room shut down for a moment, drawing a collective breath. Stansfield didn't move. Nobody moved.

After a few moments Nick Palladino and Josh Bontrager slowly crossed the room to see if Stansfield was all right. Nobody really cared all that much – no one in the room would have denied that he'd had it coming – but it didn't serve the department too well to have one of its own sprawled spread-eagle on the floor in the middle of the homicide unit duty room. Witnesses, suspects, prosecutors, and defense attorneys came through this room day and night.

Jessica glanced at Byrne. He rubbed his knuckles, picked up his coat, grabbed his keys off the desk. When he got to the door, he turned, looked at Jessica, and said: 'Call me if he's dead.'

Chapter 69

The row house on 19th Street, near Callowhill, was immaculate. Beneath the front window was a pine flower-box. In the window was a candle.

Byrne rang the bell. A few seconds later the door opened. Anna Laskaris stood there, apron on, spoon in hand, a look of confusion and expectation on her face.

'Mrs. Laskaris, I don't know if you remember me. I'm—'

'God may have taken my looks and my ability to walk more than three blocks. He didn't take away my brain. Not yet, anyway. I remember you.'

Byrne nodded.

'Come, come.'

She held the door open for him. Byrne stepped inside. If the outside of the row house was immaculate, the inside was surgically precise. On every surface was some sort of knitted item: afghans, doilies, throws. The air was suffused with three different aromas, all of them tantalizing.

She sat him at a small table in the kitchen. In seconds there was a cup of strong coffee in front of him.

Byrne took a minute or so, adding sugar, stirring, stalling. He finally got to the point. 'There's no easy way to say this, ma'am. Eduardo Robles is dead.'

Anna Laskaris looked at him, unblinking. Then she made the sign of the cross. A few seconds later she got up and walked to the stove. 'We'll eat.'

Byrne wasn't all that hungry, but it wasn't a question. In an instant he had a bowl of lamb stew in front of him. A basket of fresh bread seemed to appear out of nowhere. He ate.

'This is fantastic.'

Anna Laskaris mugged, as if this was in any doubt. She sat across from him, watched him eat.

'You married?' she asked. 'You wear no ring, but these days . . .'

'No,' Byrne said. 'I'm divorced.'

'Girlfriend?'

'Not right now.'

'What size sweater you wear?'

'Ma'am?'

'Sweater. Like a cardigan, a pullover, a V-neck. Sweater.'

Byrne had to think about it. 'I don't really buy a lot of sweaters, to be honest with you.'

'Okay. I try another door. When you buy a suit, like this beautiful suit you wear today, what size?'

'A 46, usually,' Byrne said. 'A 46 long.'

Anna Laskaris nodded. 'So then, an extra large. Maybe extra-extra.'

'Maybe.'

'What's your favorite color?'

Byrne didn't really have a favorite color. It wasn't something that crossed his mind that much. He did, however, have least favorites. 'Well, anything but pink, I guess. Or yellow.'

'Purple?'

'Or purple.'

Anna Laskaris glanced at her huge knitting basket, back at Byrne. 'Green, I think. You're Irish, right?'

Byrne nodded.

'A nice green.'

Byrne ate his stew. It occurred to him that this was the first time in a long while he was not eating in a restaurant or out of a Styrofoam container. While he ate, Anna stared off in the distance, her mind perhaps returning to other times in this house, other times at this table, times before people like Byrne brought heartache to the door like UPS. After a while, she stood slowly. She nodded at Byrne's empty bowl. 'You have some more, yes?'

'Oh God, no. I'm stuffed. It was wonderful.'

She rounded the table, picked up his bowl, brought it to the sink. Byrne could see the pain in her eyes.

'The recipe was my grandmother's. Then her grandmother's. Of the many things I miss, it's teaching Lina these things.'

She sat back down.

'My Melina was beautiful, but not so smart always. Especially about the men. Like me. I never did too well in this area. Three husbands, all bums.'

She looked out the window, then back at Byrne.

'It's a sad job what you do?'

'Sometimes,' Byrne said.

'A lot of times you come to people like me, give us bad news?'

Byrne nodded.

'Sometimes good news?'

'Sometimes.'

Anna looked at the wall next to the stove. There were three pictures of Lina – at three, ten, and sixteen.

'Sometimes I am at the market, I think I see her. But not like a grown-up girl, not like a young woman. A little girl. You know how little girls sometimes go off on their own, in their minds? Like maybe when they play with their dolls? The dolls to them are like real people?'

Byrne knew this well.

'My Lina was like this. She had a friend who was not there.'

Anna drifted away for a moment, then threw her hands up. 'We have a saying in Greece. The heart that loves is always young. She was my only grandchild. I will never have another. I have no one left to love.'

At the door Anna Laskaris held Byrne for a moment. Today she smelled of lemons and honey. It seemed to Byrne that she was getting smaller. Grief will do that, he thought. Grief needs room.

'It does not make me happy this man is dead,' Anna Laskaris said.

'God will find a place for him, a place he deserves. This is not up to you or me.'

Byrne walked to the van, slipped inside. He looked back at the house. There was already a fresh candle in the window.

He had grown up in the mist of the Delaware, and always did his best thinking there. As he drove to the river Kevin Francis Byrne considered the things he had done, the good and the bad.

You know.

He thought about Christa-Marie, about the night he met her. He thought about what she had said to him. He thought about his dreams, about waking in the night at 2:52, the moment he placed Christa– Marie under arrest, the moment everything changed forever.

You know.

But it wasn't you know. He had played back the recording he'd made of himself sleeping, listened carefully, and it suddenly became obvious.

He was saying blue notes.

It was about the silences between the notes, the time it takes for the music to echo. It was Christa-Marie telling him something for the past twenty years. Byrne knew in his heart that it all began with her. It would all end with her.

He looked at his watch. It was just after midnight.

It was Halloween.

Chapter 70

Sunday, October 31

I listen to the city coming to the day, the roar of buses, the hiss of coffee machines, the clang of church bells. I watch as leaves eddy from the trees, cascading to the ground, feeling an autumn chill in the air, the shy soubrette of winter.

I stand in the center of City Hall, at the nexus of Broad and Market streets, the shortest line between the two rivers, the beating heart of Philadelphia. I turn in place, look down the two great thoroughfares that cross my city. On each I will be known today.

The dead are getting louder. This is their day. It has always been their day.

I put up my collar, step into the maelstrom, the killing instruments a comfortable weight at my back.

What a saraband.

Zig, zig, zag.

Chapter 71

The massive stone buildings sat atop the rise like enormous birds of prey. The central structure, perhaps five stories tall, one hundred feet wide, gave way at either end to a pair of great wings, each of which bore a series of towers that fingered high into the morning sky.

The grounds surrounding the complex, at one time finely manicured, boasting Eastern Hemlock, Red Pine, and Box Elder, had fallen fallow decades earlier. Now the trees and shrubs were tortured and diseased, ravaged by wind and lightning. A once impressive arched stone bridge over the man-made creek that ringed the property had long ago crumbled.

In 1891 the archdiocese authorized and built a cloister on top of a hill, about forty miles northwest of Philadelphia, establishing a convent. The main building was completed in 1893, providing residence to more than four dozen sisters. In addition to the vegetables grown on the nearby fifteen acres of farmland, and grain for the artisan breads baked in the stone ovens, the fertile land around the facility provided food for shelters throughout Montgomery, Bucks, and Berks counties. The sisters' blackberry preserves won awards statewide.

In 1907 four of the sisters hanged themselves from a beam in the bell tower. The church, having trouble attracting novitiates to the nunnery, sold the buildings and property to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Five years later, with four new wings built onto the original building – including two tiered lecture halls, a pair of autopsy theaters, a state– of-the-art surgery, and a non-denominational chapel built into one of the apple groves – the Convent Hill Mental Health Facility opened its doors. With its two hundred beds, sprawling grounds, and expert staff, it soon gained a reputation as a thoroughly up-to-date hospital throughout the eastern United States.

In addition to its main purpose – the treatment and rehabilitation of the emotionally disturbed – the facility had a secure wing maintained and staffed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. In its twenty beds slept some of the most notorious criminals of the early twentieth century.

By the early 1950s the facility's funding had begun to dry up. Staff were laid off, buildings were not maintained, equipment became outdated and plagued by time and disrepair. Rumors of inhumane conditions at Convent Hill circulated. In the 1970s a documentary film was made, showing deplorable and sickening conditions. Public and political outrage followed, with a million dollars being pumped into the coffers.

By 1980 Convent Hill had once again been forgotten. More gossip of corruption circulated, as did tales of incalculable horror. But the public can only be outraged about something for so long.

Convent Hill closed for good in 1992 and its inmates and patients were moved to other state-run mental health facilities, as well as to correctional facilities throughout New York and Pennsylvania.

Over the next eighteen years the grounds were bequeathed to the elements, the vandals, the ghost-hunters and derelicts. A few attempts were made to secure the facility, but with its nearly two hundred acres and many points of entry, much of it surrounded by forest, it was impossible.

The fieldstone wall near the winding road that led up to the entrance still bore a sign. As Kevin Byrne and Christa-Marie Schönburg approached, Byrne noticed that someone had altered the sign, painting over it, rewording the message. It no longer announced entry to what had once been a state-of-the-art mental-health facility, a place of healing and rehabilitation, a place of serenity and peace.

It now announced entry to a place called Convict Hell.

As they drove the twisting road leading to the main buildings, a thin fog descended. The surrounding woods were cocooned in a pearl-gray mist.

Byrne thought about what he was doing. He knew the clock was ticking, that he was needed back in the city, but he also believed that the answers to many of his questions – past and present – were locked inside Christa-Marie's mind.

'Will you come back on Halloween?' she had asked. 'I want to show you a special place in the country. Well make a day of it. We'll have such fun.'

A special place.

Christa-Marie wanted him to come here for a reason.

Byrne knew he had to take the chance.

Once they crested the hill the ground leveled off, but the fronts of the buildings were still somewhat obscured by pines, evergreens, and barren maples. The walkways were crosshatched in rotting branches, matted with fallen needles. The arched entrance was flanked by two massive rows of Palladian windows. The roof boasted a main cupola, with two smaller watchtowers.

As he parked the van Byrne heard the call of larks, announcing an impending storm. The wind began to rise. It seemed to encircle the stone buildings like a frigid embrace, holding inside its many horrors.

Byrne got out of the vehicle, opened Christa-Marie's door. She gave him her delicate hand. They walked up the crumbling steps.

The two immense oak doors were secured by large rusted hinges.

Over the years the doors had been marked with epithets, pleas, confessions, denials. To the right of the entry was an inscription carved in the weathered stone.

Christa-Marie turned, an animated look on her face.

'Take a picture of me,' she said. She smoothed her hair, adjusted the silk scarf at her neck. She looked beautiful in the pale morning light.

Taking a photograph was the last thing Byrne had expected to do. He took out his cellphone, opened it, framed Christa-Marie in the doorway, and snapped.

A moment later he pocketed his phone, put a shoulder to one of the huge doors, pushed it open. A cold breeze rushed through the atrium, bringing with it years of mildew and decay.

Together they stepped over the threshold, into Christa-Marie Schönburg's past, into the infernal confines of Convent Hill.

Chapter 72

The dead walk here. The dead and the insane and the forgotten. If you come with me, and hear what I hear, there is much more than the whistle of the wind.

There is the young man who came here in 1920. He had been wounded at St. Mihiel Salient. He bleeds from both wrists. 'I am going home,' he says to me. 'First to Pont-a-Mousson, then home.'

He never left.

There is the solicitor from Youngstown, Ohio. Twice he has tried to take his life. His neck is deeply scarred. He cannot speak above a whisper. His voice is a dry wind in the night desert.

There are the two sisters who tried to eat each other's flesh, found in the basement of their Olney row house, locked in an embrace, wrapped in barbed wire, blood dripping from their lips.

They gather around me, their voices lifted in a chorus of madness.

I walk with my lover.

I walk with the dead.

Chapter 73

They strolled arm in arm through the hallways, their heels echoing on the old tiles. A powdery light sifted through the windows.

Overhead was a vaulted ceiling, at least thirty feet high, and on it Byrne saw three layers of paint, each a dismal attempt at cheerfulness. Lemon yellow, baby blue, sea-foam green.

Christa-Marie pointed to a room off the main entry. 'This is where they take you on arrival,' she said. 'Don't let the flowers fool you.'

Byrne peeked inside. The remains of a pair of rusted chains, bolted to the wall, lay on the ground like dead snakes. There were no flowers.

They continued on, deeper into the heart of Convent Hill, passing dozens of rooms, rooms pooled with stagnant water, rooms tiled floor to ceiling, grout stained with decades of mold and long-dried blood, drains clogged with sewage and discarded clothing.

One room held six chairs still in a semicircle, the cane seats missing, one chair curiously facing away from the others. One room had a three-tiered bunk bed bolted to the floor over a decayed Oriental rug. Byrne could see where attempts had been made to tear away the rug. Both ends were shredded. Three brown fingernails remained.

One room, at the back of the main hallway, had rusted steel buckets lined against the wall, each filled with hardened feces, white and chalky with time. One bucket had the word happy painted on it.

They took the winding staircase to the second floor.

In one meeting room was a slanted stage. Above the stage, on the fascia, was a large medallion made of crisscrossed black string, perhaps an occupational-therapy project of some sort.

They continued through the wing. Byrne noted that many of the individual rooms had observation windows, some as small and simple as a pair of holes drilled into the door. Nothing, it seemed, went unobserved at Convent Hill.

'This was Maristella's room,' Christa-Marie said. The room was no larger than six by six feet. Against the wall, a long-faded pink enamel, were three threadbare stretchers. 'She was my friend. A little crazy, I think.'

The massive gymnasium had a large mural, measuring more than fifty feet long. The background was the rolling hills surrounding the facility. Scattered throughout were small scenes, all drawn by different hands – hellish depictions of rape, murder, and torture.

When they turned the corner into the east wing, Byrne stopped in his tracks. Someone was standing at the end of the wide hallway. Byrne could not see much. The person was small, compact, unmoving.

It took Byrne a few moments to realize, in the dim light, that it was only a cutout of a person. As they drew closer, he could see that it was a plywood pattern of a child, a boy perhaps ten or twelve years old. The figure wore a yellow shirt and dark brown pants. Behind the figure, on the wall, was painted a blue stripe, perhaps meant to mimic the ocean. As they passed the figure, Byrne saw pockmarks in the plywood, along with a few holes. Behind the figure were corresponding holes. At some point the figure had been riddled with bullets. Someone had drawn blood on the shirt.

They stopped at the end of the hall. Above them the roof had rotted away. A few drops of water found them.

'You know at the first note,' Christa-Marie said.

'What do you mean?'

'Whether a child has the potential to be a virtuoso.' She looked at her hands, her long, elegant fingers. 'They draw you in. The children.

At Prentiss they asked me a hundred times to teach. I kept refusing. I finally gave in. Two boys stood out.'

Byrne took her hand. 'Who are these boys?'

Christa-Marie did not answer right away. 'They were there, you know,' she eventually said.

'Where?'

'At the concert,' she said. 'After.'

There was a sound, an echoing sound from somewhere in the darkness. Christa-Marie seemed not to notice.

'That night, Christa-Marie. Take me back to that night.'

Christa-Marie looked at him. In her eyes he saw the same look he had seen twenty years earlier, a look of fear and loneliness.

'I wore black,' she said.

'Yes,' Byrne said. 'You looked beautiful.'

Christa-Marie smiled. 'Thank you.'

'Tell me about the concert.'

Christa-Marie glided across the corridor, into the semi-darkness. 'The hall was decorated for the holidays. It smelled of fresh pine. We debated fiercely over the program. The audience was, after all, children. The director wanted yet another performance of Peter and the Wolf:

Byrne expected her to continue. She did not. Her eyes suddenly misted with tears. She walked slowly back, reached into her bag, retrieved a piece of paper, handed it to Byrne. It was a letter, addressed to Christa-Marie and copied to her attorney, Benjamin Curtin. It was from the Department of Oncology at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital. Byrne read the letter.

A few moments later he took her hands in his. 'Will you play for me tonight?'

Christa-Marie moved closer. She put her arms around him, her head on his chest. They stood that way for a long time, not moving, not speaking. She broke the silence first.

'I'm dying, Kevin.'

Byrne stroked her hair. It was silken to his touch. 'I know.'

She nestled closer. 'I can hear your heart. It is steady and strong.'

Byrne looked out the window, at the fogbound forest surrounding Convent Hill. He remained silent. There was nothing to say.