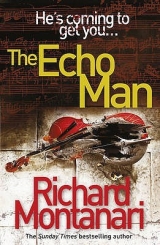

Текст книги "The Echo Man"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Chapter 24

The house in Lexington Park was nearly empty, save for the hundred or so boxes stacked in the attic, upper hallway, living room and kitchen. The furniture was gone. The dining-room chandelier, an heirloom passed down from Jessica's grandmother, had been carefully packed and spirited away, as had all her mother's cut-crystal goblets.

Three dozen people crowded the first floor, eating wings and crab fries from Chickie's and Pete's. Among them were a who's who from the police department, crime lab and district attorney's office. Chits cashed, favors recalled, Jessica had been batting her eyelashes for weeks; Vincent had been twisting arms, sometimes literally, for months.

Also downstairs were Jessica's father Peter Giovanni, most of her cousins, Colleen Byrne and her friend Laurent, Byrne's father Paddy. Just about everyone who could be roped in was in attendance.

Byrne arrived a little late.

Jessica and Byrne stood at the top of the stairs, at the entrance to the attic. Before them was arrayed a roomful of boxes.

'Wow,' Byrne said.

'I'm a total pack rat, aren't IP'

Byrne looked around, shrugged. 'It's not that bad. I've seen worse. Remember the old lady on Osage, the one with two hundred cats?'

'Thanks.'

Jessica noticed some hair on Byrne's shoulder. She reached over, brushed it off.

'Did you get a haircut?'

'Yeah,' he said. 'I popped in and got a trim.'

'You popped in?'

'Yeah. No good?'

'No, it looks fine. It's just that I've never "popped in" for a haircut. It takes me four to six weeks to make the decision, then it's another month of doubt, steering committees, estimates, near misses, appointments cancelled at the last second. It's a life-changing event for me.'

'Well, it's pretty much a haircut for me.'

'You have it so easy.'

'Oh yeah,' Byrne said. 'My life's a Happy Meal.'

Jessica lifted a few boxes that were, mercifully, light. At least she had taken to labeling things in the past few years. This one read ST. PATRICK'S DAY ORNAMENTS. She did not remember ever buying or displaying St. Patrick's Day ornaments. It looked like she was going to keep them nonetheless, so she could not use them in the future. She put the box by the top of the stairs, turned back.

'Let me ask you something,' she said.

'Shoot.'

'How many times have you moved in the last ten years?'

Byrne thought for a few moments. 'Four times,' he said. 'Why?'

'I don't know. I guess I was just wondering if you're still hanging onto a bunch of completely pointless, useless crap.'

'No,' Byrne said. 'Everything I have is absolutely necessary. I'm a Spartan.'

'Right. You should know that I once talked to Donna about this very thing.'

'Uh-oh.'

In the past few years Jessica and Byrne's ex-wife Donna had become good friends.

'Oh yeah. And she said that when you guys were married, and you moved from the apartment into your house, the first thing you packed was your Roger Ramjet nightlight.'

'Hey! That was a safety issue, okay?'

'Uh-huh. Still have it?'

'I do not,' Byrne said. 'I have a Steve Canyon nightlight now. Roger Ramjet is for kids.'

'Tell you what,' Jessica said. 'I will if you will.'

It was a game they sometimes played – like Truth or Dare, but without the dare. Ninety-nine percent of the time is was light-hearted. Once in a while it was serious. This was not one of those times. Still, there were rules.

'Sure,' Byrne said. 'You're on.'

'Okay. What is the most ludicrous piece of clothing you still own? I mean, something you know you will never wear again, not in a million years, but you just can't bring yourself to part with it?'

'That's an easy one.'

'Really?'

'Oh yeah,' Byrne said. 'A pair of 33-inch waist green velvet pants. Real plum-smugglers.'

Jessica almost laughed. She cleared her throat instead. No laughing was one of the big rules of the game. 'Wow.' It was all she could muster.

'Is that wow I once had a 33-inch waist, or wow green velvet?'

This was a no-win question. She opted for the velvet.

'Well,' Byrne said. 'I bought them in New York in my Thin Lizzy days. I really wanted to be Phil Lynott. You should have seen me.'

'I would pay good money for that,' Jessica said. 'A lot of women in the department would chip in, too.'

'What about you?'

Jessica glanced at her watch. 'My God. Look at the time.'

'Jess.'

'Okay. When I was nineteen, going to Temple, I had a date with this guy – Richie Randazzo. He invited me to his cousin's wedding in Cheltenham and I saved for three months for the cutest little red dress from Strawbridge's. It's a size four. I still have it.'

'What, you're not a size four?'

'You are the greatest man who has ever lived.'

'As if this were in doubt,' Byrne said. 'One question, though.'

'What?'

'You went out with a guy named Richie Randazzo?'

'If you didn't factor in the mullet, the rusted-out Toronado with the fur-trimmed rearview mirror, and the fact that he drank Southern Comfort and Vernor's, he was kind of cute.'

'At least I never had a mullet,' Byrne said. 'Ever.'

'I could always check with Donna, you know.'

Byrne looked at his watch. 'Look at the time.'

Jessica laughed, letting him off the hook. She fell silent for a few moments, looking around the attic. It occurred to her that she would never be back in this room. 'Man.'

'What?'

'My whole life is in these boxes.' She opened a box, took out some photos. On top were pictures of her parents' wedding.

Out of the corner of her eye Jessica saw Byrne turn away for a second, giving her the moment with her memories. Jessica put the photos back.

'So, let me ask you one more thing,' she said.

'Sure.'

Jessica took a few seconds. She hoped that her voice was going to be steady. She put her hand on one of the boxes, the one with the piece of green yarn around it. 'If you have something, some memento that is a part of your life, and you know that the next time you see it, it's going to break your heart, do you keep it? Do you hold onto it anyway? Even though you know it is going to cause you pain the next time you look at it?'

Byrne knew that she was talking about her mother.

'Do you remember her well?' he asked.

Jessica had been five years old when her mother died. Her father had never remarried, had never loved another woman. 'Yeah. Sometimes. Not her face, though. I remember how she smelled. Her shampoo, her perfume. I remember how in summer, when we went to Wildwood, she smelled like Coppertone and cherry Life Savers. And I remember her voice. She always sang with the radio.'

Heaven Must Have Sent You. It was one of her mother's favorites. Jessica hadn't thought of that song in years.

'How about you?' she asked. 'Do you think about your mom a lot?'

'Enough to keep her alive,' Byrne said and leaned against the wall. It was his storytelling pose.

'When I was a kid, and my father used to chew me out, my mother would always run interference, you know? I mean physically. She would physically get in between us. She wouldn't make excuses for me, and I always ended up getting punished, but while my father was upbraiding me she would stand with her hands clasped behind her back. I'd look at her hands, and she always had a fifty cent piece for me. My father never knew. I'd have to do my time, but afterwards I always had fifty– cents to blow on a water ice or a comic book when I got paroled.'

Jessica smiled, thinking about anyone – especially Paddy Byrne – intimidating her partner.

'She died on my birthday, you know,' Byrne said.

Jessica didn't know. Byrne had never told her this. At that moment she tried to think of something sadder than this, and found herself at a loss. 'I didn't know.'

Byrne nodded. 'You know how you always notice your birthday when you see it printed somewhere, or hear it mentioned in a movie or on television?'

'Yeah,' Jessica said. 'You always turn to the people around you and say hey . . . that's my birthday.'

Byrne smiled. 'It's like that for me when I go to the cemetery. I always do a double take when I see the headstone, even though I know.' He put his hands in his pockets. 'It will never be my birthday again. It will always be the day she died, no matter how long I live.'

Jessica couldn't think of anything to say. It mattered little, because she had never met a more perceptive person than Kevin Byrne. He always knew when to move things along.

'So, your question?' he asked. 'The one about whether or not to save something, even though you know it will break your heart?'

'What about it?'

Byrne reached into his pocket, pulled something out. It was a fifty-cent piece. Jessica looked at the coin, at her partner. At this moment, his eyes were the deepest emerald she had ever seen.

'It's a strange thing about heartbreak,' Byrne said. 'Sometimes it's the best thing for you. Sometimes it reminds you that your heart is still beating.'

They stood, saying nothing, cosseted in this drafty room full of memory and loss. The silence was shattered by the sound of a breaking dish downstairs. Irish and Italians and booze always led to broken ceramics. Jessica and Byrne smiled at each other, and the moment dissolved.

'Ready for the big bad city?' he asked.

'No.'

Byrne picked up a box, headed for the stairs. He stopped, turned. 'You know, for a South Philly chick, you turned into kind of a wimp.'

'I have a gun in one of these boxes,' Jessica said.

Byrne ran down the steps.

Chapter 25

By ten o'clock they had everything in the new house. What had seemed like a reasonable amount of goods in the Lexington Park house now filled up every room, every corner, every cabinet. If they put the sofa and two of the dining-room chairs on the roof, they could just about make everything fit.

Byrne stood across the street from the row house. A pair of older teenage girls walked by, reminding him of Lucy Doucette.

When he had first met Lucy at the group regression-therapy sessions she had seemed so lost. He did not know much about her life, but she had told him enough for him to know that she was troubled by a traumatic event in her childhood. He recalled her efforts at the regression-therapy group, her inability to recall anything about the incident. He didn't know if she had been molested or not. Running into her accidentally in the city reminded him how he had promised to look in on her from time to time. He had not.

'Kevin?'

It was a tiny voice. Byrne turned around and saw that it was Jessica's daughter Sophie, bundled up, standing on the sidewalk in front of the porch. The front door was open, and through it Byrne could see Peter Giovanni inside, leaning against the handrail, keeping one eye on his granddaughter. Once a father, always a cop.

Byrne crossed the street. For a long time Jessica had insisted that

Sophie should call him Mr. Byrne. It had taken a while for Byrne to change that, and it looked like it had finally taken hold. Byrne got down to Sophie's level, noticing that she wasn't as small as she had been even last year at this time. 'Hey, sweetie.'

'Thanks for helping out.'

'Oh, you're welcome,' Byrne said. 'Do you like your new house?'

'It's small.'

Byrne looked over her shoulder. 'It's not that small. I think it's pretty cool.'

Sophie shrugged. 'It's all right, I guess.'

'Plus your school is only a block away. You can sleep late.'

Sophie giggled. 'You don't know my mom.'

The truth was, he did. He soon realized the folly of his statement.

Sophie glanced up the street. The looming structure of Sacred Heart Parochial School was silhouetted against the carbon-blue night sky. She looked back at Byrne. 'Did you go to Catholic school?'

'Oh yeah,' Byrne said. He wanted to tell her that he still had ruler marks on his knuckles to prove it, but decided against it.

'Did you like it?'

How to answer this? 'Well, do you have a kid in your school who is always goofing off, always getting into trouble?'

'Yeah,' Sophie said. 'In my school it's Bobby Tomasello.'

'Well, in my school that kid was me.'

'You got into trouble?'

'All the time,' Byrne said.

'Did they make you sit in the corner?'

Byrne smiled at the memory. 'Let me put it this way. Sister Mary Alice ended up putting my desk in the corner. It saved everyone a trip. In fact, I had a corner office in every one of my classrooms.'

Sophie's face softened into an expression that Byrne had seen a thousand times on Jessica's face, a look of compassion and understanding. 'It's all right, Kevin,' she said. 'You turned out okay.'

The jury was still out on that one, Byrne thought. Still, it was nice to hear, even if it was coming from a seven-year-old. Maybe especially from a seven-year-old. 'Thanks.'

They fell silent for a moment, listening to the sounds of the party coming from inside the house.

'I like Colleen,' Sophie said.

'Yeah,' Byrne said. 'She's pretty special.'

'She taught me something.'

'Oh yeah?'

Sophie nodded. She thought for a moment, wrinkling her brow, then balled her fists, extended a finger, stopped, thought a bit more, started over. This time she extended her hands, rubbed one palm across the other, lifted the index finger on each hand, bumped fists, and pointed at Byrne.

It was American Sign Language for 'Nice to meet you.'

'Very good,' Byrne said. 'Did you just learn that?'

Sophie nodded. 'It took me a few times.'

Byrne smiled. 'It took me -way more than a few times.'

A few minutes later he kissed Sophie on top of her head, watched her walk back inside. After she was inside, Byrne stood and observed Jessica's family through the window for a while. It had been a long time since he'd been part of something like this.

He thought about Sophie's sign language, how determined she was, how she stayed with it until she got it right. He considered how the oldest sayings were the truest, like that one about the apple not falling far from the tree.

Byrne walked down Third Street, got into the van. He had grown up not far from here. He remembered a variety store on the corner. He used to get his water pistols and comic books there, cadging the occasional Baby Ruth and Butterfinger. He remembered a kid who got beat up once in the alley behind the store, a kid who was thought to have molested a little girl from the neighborhood. Byrne had been sitting on the corner with his cousin Patrick when it happened. He remembered the kid screaming. It was the first time he had ever encountered violence like that, the first time he had ever heard someone in so much pain. He believed that all those sounds, all the dark echoes of violence, in many ways remained.

Byrne sat there for a long time, not moving, just rolling the fifty– cent piece over his fingers, the memories of his old neighborhood misting across his mind.

Someone emerged from the shadows just outside the driver's side window of the van. Byrne sat upright. It was Jessica. He rolled down the window.

'What's up?' he asked. 'Ready to move back already?'

'You know the paper that was wrapped around the victims' heads?'

'What about it?'

'We have a make.'

Chapter 26

The crime lab – officially known as the Forensic Science Center, but never called that – was a massive building that had once been a schoolhouse, located just a few blocks from the Roundhouse at Eighth and Poplar Streets.

The reigning sovereign of the documents section was Sergeant Helmut Rohmer. Hell Rohmer was thirty-five, and a giant, measuring six-four, weighing two-fifty. Besides his strange and eclectic taste in music, which ran from Iron Maiden to Kitty Wells, he was known for his T-shirts – always black, never bearing the same saying twice. He must have had hundreds. He was starting to receive them in the mail, even from people he had helped put away in prison. Today his shirt read:

PADDLE FASTER.

I HEAR BANJOS.

His considerable arms were ringed with rose tattoos, or some variation, which now finished with ivy circling his wrists and ending on the backs of his hands. He was always well-groomed – right down to his oddly manicured fingers. Jessica figured that his manicures had something to do with his sense of the tactile. Hell Rohmer didn't want anything interfering with his sense of touch. He was almost metaphysical in his approach to document forensics. It was one of the reasons why he and Byrne spoke the same language.

'Good evening, sleuths,' Hell said.

'Good evening, alchemist,' Byrne replied.

Hell smiled. 'I have your paper,' he said. 'You can only hide from the Weavemeister for so long.'

On the wall were six enlarged photographs of the paper found on the victims, front and back. The photographs showed the blood that had leached from the lacerations on each of the victim's foreheads, as well as the small dot of blood from the shallow puncture wound. A line, a dot, and the rough figure eight where the ears were mutilated.

'What do we have?' Jessica asked.

Hell picked up a small square of the paper sample, cut from the end of one of the bands. 'This is pricey stuff,' he said, running a finger across the slightly pebbled surface. 'It's beautiful, really. Our boy has exquisite taste.' Hell zoned for a moment, his eyes going a bit unfocused. Hell Rohmer was definitely a touchy-feely sort of guy.

'Hell?'

'Okay. Sorry. The paper is handmade, a hundred percent cotton, acid-free. Which puts it into the same category as about ten thousand brands. I'm not equipped to do a comparison test to determine the make, and I was just about to send it off to the FBI – which, as you know, can take a month or two to get back – when I saw something.' Helmut held up a sample. 'This was cut from the paper we took from the female victim. If you look here, you can see a small segment of a watermark.' Hell held the paper up to a strong light, but not too close. Jessica saw what looked like the portion of a shoulder.

'Is that a cherub of some sort?' Jessica asked.

Hell shook his head. 'The watermark is Venus de Milo. It's not on the other sample, so I'm thinking these were cut from a larger sheet.'

Hell displayed another printout. It was an extreme close-up of the edge of the paper, photographed through a microscope. 'This was cut with a large blade, which is indicated by the slight tearing of the fiber. I think he used a paper cutter, instead of an X-acto blade, scissors, or razor blade. The shearing is consistent front to back, with the fibers pushed downward. Too uniform to have been done by hand.'

Hell pointed to the sample.

'And while this might look white, it is really Felt Light Grey. Deckled on two sides, which leads me to believe it's deckled on four. The band is twenty-four inches long, which leads me to believe it was cut from a sheet that was twenty-four by twenty-six, which is fairly standard in printmaking.'

'This is printmaking paper?'

'Among other things.'

Hell put the sample down, picked up a few pages of computer printouts.

'It's the watermark that jumped out. Without it, we would have had to wait for Washington on this.' He pointed to one of the lines on the printout, highlighted in lime green. 'The manufacturer of this paper is headquartered in Milan, Italy, and the line is called Atriana. Really high-end stuff. Printmaking, mostly, but they make all kinds of multi-use paper – stationery, canvas, vellum, linen. But this stuff is top of the line. One sheet of this paper retails for about seventy dollars.'

'Wow'

'Yeah,' Hell said. 'And dig this. This company also supplies the paper for the Euro.'

'The currency?'

'The one.'

'They have two distributors in the US,' Hell said. 'As far as I can tell this paper is available at only twenty retail stores across the country. Mostly art supplies and specialty paper shops. Unfortunately – for us, not our bad boy – the paper can be ordered from a dozen online retailers.'

'Are there any stores in Philly that carry it?' Jessica asked.

'No,' Hell said. He smiled, held up a 3 x 5 card with an address on it. 'But there is a store in Doylestown.'

Jessica took the address.

'No applause?'

Jessica clapped.

'Thank you. And now to the wax.' On the table sat a small covered glass dish. The wax seal was inside. 'This is standard candle wax, not sealing wax, which is why it has begun to disintegrate.'

'What's the difference?'

'Well, about five hundred years ago, sealing wax was made primarily of beeswax and something called Venice turpentine, which is an extract of the larch tree. The wax was uncolored in those days, but when the Renaissance hit, folks started to color it with vermilion, and do you really want to know any of this?'

'Maybe one of these days,' Jessica said. 'Right now I'd love to know where our boy bought this. I would like a clear video of him leaving the store, and a copy of his driver's license. Do you have that?'

'No. And what's worse, this candle wax is available at every Rite– Aid, Wal-Mart and Target in the country. But not in this color.'

'What do you mean?'

'Well, what I was getting to, before I was so brusquely interrupted, was that this particular sample was not colored with any old vermilion.'

It took Jessica a second to realize what Hell Rohmer was saying. One look at Byrne told her he'd gotten it as well. She turned back to Hell.

'No.'

'I'm afraid so. The coloring is blood. This is a bad, bad pony, this guy.'

Jessica looked at Byrne just as someone entered the lab and stopped by the door. Hell crossed the room, disappeared from Jessica's line of sight. In the reflection from one of the glass cabinets she saw that the new arrival was Irina Kohl. Irina had with her a few folders, one of which she placed in Hell's hands. Then Jessica saw the diminutive Irina get on her tiptoes and kiss Hell Rohmer flush on the mouth. Hell turned and saw that Jessica could see them in the cabinet's reflection.

The two of them, now red as raspberries, walked back to join Jessica and Byrne.

'Urn, you didn't see that,' Hell whispered to Jessica.

'See what?'

Hell winked.

'I'm glad you're here,' Irina said, plowing forward. 'I think we may have something on the murder weapon.'

Irina Kohl worked in the lab's firearms ID unit, which also handled tool marks, and was in her late twenties, a prototypical lab dweller – neat in appearance, precise in manner and speech, probably a little too smart for Mensa. Beneath her lab coat she wore a suit coat, white button-down shirt, and lavender knit tie.

Irina opened a folder, removed some enlargements.

'The wire used as the ligature was made of woven multi-strand titanium.' She pointed to an extreme close-up of the ligature marks on the first two victims. Even to the naked eye the woven characteristics were visible. The flesh bore an imprint of the three-strand weave. 'We found traces of the metal in the wound.'

'What is something like this used for?' Jessica asked.

'There are a lot of uses for it. In general, titanium wire is specified for medical devices, bone screws, orthodontic appliances. In different gauges it is all over the aerospace, medical and marine manufacturing map. It is low-density and has a high resistance to corrosion.'

Irina then picked up a blown-up photograph, as well as a pair of slides.

'I also found hair samples in the ligature wound on the first two victims. We haven't gotten a crack at the third victim yet.' She pointed to the two slides. 'These are from Sharon Beckman and Kenneth Beckman.'

'Do you think this is our killer's hair?' Jessica asked.

'No,' Irina said. 'I'm afraid not. These samples are definitely not human.'

Jessica looked at Byrne, back. 'Not human as in ...'

'Well, animal.' Irina pushed up her thick glasses. She scrunched her face, as if smelling something unpleasant. Jessica supposed this was her way of waiting for the conversation to regenerate. She also noted that the woman was wearing two different lipsticks. One shade on her upper lip, one on the lower.

'Well, duh, Jess,' Jessica said, berating herself. 'I mean, what else, alien?'

Irina continued, undaunted. 'Domestic animal specifically.'

'We're talking dog or cat?' Jessica asked.

'Not domesticated, necessarily. What I mean is domestic as in cow, sheep, horse.' Irina got a little more animated. 'See, if we're talking the hair of domestic animals there are a number of variations in color and length. However, a lot of these identifiers are pretty general. In order to tell the difference between, say, a dog and a cat, or between a cow and a moose, you really need the root to be present. Which, unfortunately, in this case, we do not have.'

She slipped a slide onto the stage of a microscope, clipped it in.

'But we're just getting started.' Irina smiled at Hell. Hell beamed.

Irina then peered into the microscope eyepiece, did a little fine focusing. 'If you take a look here, you can see it.' She stepped back.

Jessica stepped forward, looked through the microscope.

'You see it is quite coarse. The medulla is unbroken,' Irina said. 'The pigment is fine and evenly distributed.'

'Yeah,' Jessica said. 'I was just going to say that about the medulla.' The image she saw looked like a long dark brown tube. She might just as well have been looking at a Tootsie Roll. Hell Rohmer watched Irina, sunny with admiration, seething with forensic lust. Jessica and Byrne had worked with the two of them many times. Hell and Irina liked to have scientifically clueless detectives and other investigators look though microscopes. It validated them as criminalists.

'What tipped me was the ovoid structures,' Irina added.

'Every time,' Jessica said, stepping away from the microscope. 'So what are you saying? I mean, I understand it. Tell us for Kevin's benefit.'

Byrne smiled.

'Well, this is not exactly my field,' Irina said. 'So I'm going to send this out. We should know something by tomorrow at the latest.'

Jessica handed Irina a card with her cellphone number on it. 'Call me the second you have it.'

'Will do,' Irina said. 'And our freaky killer better get some game.'

'Why's that?'

Irina smiled. Jessica saw her hand covertly brush up against Hell Rohmer's hand. 'We're about to make his life awfully uncomfortable.'

On the way out to the car Jessica thought about the lab and the curious creatures who toiled within. Physical evidence was, as they say, a silent witness to every misdeed, always present at crime scenes due to the simple phenomenon of transference. No individual can enter or leave any enclosed area without picking up or leaving behind innumerable items of physical evidence. But the evidence alone has little value. Only after it has been detected, collected, analyzed, interpreted and presented will it yield meaning and context.

As a rule, criminals have no idea who the people are who plug away in forensic labs all over the world and how dedicated they are to rooting out the truth. If they did know, they wouldn't be so cavalier about leaving at their crime scenes any one of the million skin cells or hundreds of hairs we shed every day, not to mention saliva, footprints, blood, or fibers from clothing.

As Jessica got into the car she also thought about how her job sometimes resembled an episode of The X-Files.

These samples are definitely not human.