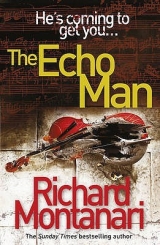

Текст книги "The Echo Man"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Chapter 38

Thursday, October 28

The city's last official potter's field had opened in 1956 in Philadelphia's Northeast. Prior to its opening, the most active potter's field had been in a section now used as a police parking lot at Luzerne Street and Whitaker Avenue, adjoining Philadelphia Municipal Hospital, where it became the final resting place for thousands who died in the 1918 flu epidemic. At various times in the city's history, indigent or unclaimed deceased were buried in a number of places, including Logan Square, Franklin Field, Reyburn Park, even at the corner of 15th and Catharine, just a few blocks from where Jessica had grown up.

These days, in the interest of logistics and expense, many of the unidentified and indigent were being cremated, with remains stored in a room off the morgue at the medical examiner's office.

Jessica and Byrne visited the zoning-archives department of Licenses and Inspections at just after eight a.m. The L & I office was located in the Municipal Services Building at 15th and JFK. What they learned was that there had once been a potter's field located in the Parkwood section of Northeast Philadelphia, a field that had since closed.

They stopped for coffee and got onto 1-95 at just after nine a.m.

The field was located near the intersection of Mechanicsville Road and Dunks Ferry Road at the southern end of Poquessing Valley Park.

On the south side of Dunks Ferry Road were blocks of two-story twin row homes, their fasciae festooned with Halloween decorations ranging from the elaborate (one had a skeleton about to climb down the chimney) to the ordinary (an already dented plastic pumpkin stuck on a gas light).

Jessica and Byrne got out of the car, crossed the road. They walked through the trees into a large open field. Here the ground was rippled – the uneven remnants of graves that had been there a long time.

There were no headstones, no crypts, no vaults, no mausoleum. The field had indeed been closed, the bodies moved or cremated, the area planted over.

Jessica looked at the rutted sod. She considered the generations of kids to come, flying kites, playing kickball, unaware that at one time the ground beneath their feet had held the remnants of the city's homeless, its indigent, its lost.

They walked slowly across the undulating earth, looking for any sign of what had once been there – a buried headstone, a grave marker of any kind, a stake in the ground indicating the boundaries of the cemetery. There was nothing. The earth had long ago begun to reclaim the area with life.

'Was this the only city field in this area?' Jessica asked.

'Yeah,' Byrne said. 'This was it.'

Jessica looked around. Nothing looked promising, at least as it might concern the cases. 'We're wasting our time up here, aren't we?'

Byrne didn't reply. Instead he crouched down, ran his hand over a bare patch of ground. A few moments later he stood, dusted off his hands.

Jessica heard a rustling in the nearby trees. She looked up to see a half-dozen crows perched tenuously on a low branch of a nearby maple. A murder of crows, she had once learned, and had ever since thought how odd a term that was. A flock of geese, a herd of cattle, a murder of crows. Soon another black bird landed, rustling the others, who responded with a series of loud caws and flapping wings. One of them took off and swooped toward the low shrubs at the other side of the field. Jessica followed the pattern of flight.

'Kevin,' she said, pointing to the bird before it landed out of sight. They looked at each other, started across the open field.

Before they got halfway they saw it – the unnatural gleam through the greenery, the bright white surface glinting in the sunlight.

They sprinted the last hundred feet or so and found the body lying in a shallow depression.

The victim was black, male, in his forties or fifties. He was nude, his body shaven head to toe. The ground beneath the corpse was not yet overgrown with grass. It was a former grave.

'Motherfucker,' Byrne yelled.

He stepped through the scene, taking care not to disturb the surrounding area. He put two fingers to the man's neck. 'Jesus Christ,' he said. 'His body's still warm. Let's get everyone and his mother down here. Let's get a K-9 unit.'

Then Byrne gently opened the dead man's hand. There, on the ring finger of his left hand, was the tattoo of a fish.

They both called it in – Byrne contacted the crime-scene unit, Jessica contacted the homicide unit who would then alert the MEO. They spread out to either side of the open field, weapons out. They checked the immediate area, combing the bushes, the scrub, the culverts and ditches, finding nothing.

Later they regrouped at the corner, each lost in their own thoughts. Although they had not immediately located any ID, there was no doubt in either Jessica's or Byrne's mind that the body they'd found – the dead man lying atop a former grave – was that of Tyvander 'Hoochie' Alice.

The tactical team hit the block in six cars, a combination of special– investigation detectives and members of the fugitive squad.

Russ Diaz and his squad fanned out north and east, toward the woods. A K-9 unit showed up a few minutes later. The next car brought Dana Westbrook. For the moment, this relatively quiet corner of Northeast Philadelphia – a place that had one time been a place of repose and solitude – was crawling with law-enforcement personnel.

Ten minutes later the dog and his officer came full circle, back to the parking area near the ball diamonds. It probably meant that the killer had parked there, returned after dumping the body, and then left. If that was so, the trail was cold.

While CSU processed the crime scene, Jessica and Byrne stood at the top of the hill, watching the choreography unfold below.

Detectives would soon canvass the immediate area. There was a condo development at Mechanicsville and Eddington Roads, a pair of apartments next to it. Maybe someone had seen something. But Jessica doubted it. Their killer was a ghost.

Kenneth Beckman, Sharon Beckman, Preston Braswell, Tyvander Alice.

Four bodies, eight tattoos.

Four to go.

And they didn't have a single solid lead.

The team spent the entire afternoon canvassing. The residences in this part of the city were not as tightly packed as they were in the inner city, so the act of interviewing and asking the same questions over and over was a much slower, even more enervating process.

They returned to the Roundhouse, followed up on a few weak leads. Nothing. By the end of the tour, the entire unit was exhausted and frustrated. Someone was solving the unsolved crimes in Philadelphia, but they were killing the killers and their accomplices. Someone was shaving these bodies clean, mutilating their faces, and wrapping them in paper. Someone who floated through the city like a phantom.

Jessica sat on the edge of a desk, a cup of cold coffee in her hand. She glanced over at the walk-in closet. Inside were the books of homicide cases dating back more than a hundred years. Inside the books were summaries of hundreds of unsolved cases, cases wherein there were suspects who were never charged with the crime, suspects who never became defendants, defendants who were acquitted for any number of reasons. The books were essentially a list of potential victims for their ghoul.

The duty room was mostly empty. The second tour had already begun, and those detectives were on the street, pursuing leads, tracking down witnesses. Jessica was envious.

'Don't you have a family to go home to?' Byrne asked.

'Nah,' Jessica said. 'Although, funny you should mention it, I have seen a man and a little girl hanging around my house. I should call the police.'

Byrne laughed. 'Speaking of which, how are you adjusting to the new house?'

'Well, besides tripping over the furniture and spinning in place for five minutes because there's nowhere to put a cup of coffee down, it's great.'

'Is it that much smaller?'

Jessica nodded. 'It's a lot like the house I grew up in. Same layout. The only problem is, I was a lot smaller then.'

'What, like a size four?'

'Smartass.'

Byrne's phone beeped in his hand. He looked at the screen, read for a moment, smiled.

'It's a text from Colleen,' he said. 'She wanted me to know she got back from D.C. okay.'

Jessica nodded. 'Wow,' she said. 'Colleen in college.'

'Don't remind me.'

Byrne picked up a tall stack of mail that was rubber-banded together on the desk. It looked like two weeks' worth of correspondence, mostly junk. Jessica wanted to mention to her partner that it was probably a good idea to check the inbox once in a while, but she figured he knew this.

As Byrne went through the pile, throwing most of the mail in the trash can, Jessica smelled the perfumed letter before she saw it. The scent was jasmine. Byrne held up the envelope, eyed it, sniffed it. It was the size of a personal note card, maybe four by six inches. Expensive-looking paper.

'A note from an admirer?' Jessica asked. 'As if,' Byrne replied.

'It's the charcoal gray suit, Kevin. I'm telling you.' Byrne pulled a letter opener off the desk, slit the envelope, extracted the card.

As much as Jessica wanted to pry, she stepped a few feet away, giving her partner a little privacy, shoving everything she needed to take with her into her tote bag. When she looked again at Byrne, he was bone pale. Something was wrong.

'What is it?' Jessica asked.

Byrne remained silent.

'Kevin.'

Byrne waited a few moments, then took Jessica by the arm, led her to the small coffee room, closed the door. He handed her the card. It was printed on a luxurious paper, ivory in color. The scent of jasmine was now much stronger. Jessica put on her glasses, read the note, a brief message written in an elegant hand. The ink was lavender.

My dearest Detective Byrne,

It has been a long time, n'est-ce pas? I wonder how you have fared. Do you think of me? I think of you often. In fact I dreamed of you the other night. It was the first time in years. You looked quite dashing in your dark overcoat and black fedora. You carried an umbrella with a carved ivory handle. Do you carry an umbrella as a rule? No, I would think not.

So tell me. Have you found them yet? The lion and the rooster and the swan? Are there others? You might think they do not play together, but they do. I hope you are well, and that the future brings you every happiness. I am no longer scared.

– C

Jessica was stunned. She read the note a second time, the rich scent filling her head.

'Are you fucking kidding me?' she finally said in a loud whisper. 'The lion and the rooster and the swan?'

Byrne remained silent.

'Who the hell sent this, Kevin? Who is C?'

Byrne turned the envelope over and over in his hands, searching for words. Words were usually his strong suit. He always chose them carefully. He was good at it.

He told her the story.

Chapter 39

Jessica looked at her partner. She wasn't sure how long she had been staring at him without saying anything, her mouth open, eyebrows raised. Then all she could muster was one word. 'Wow.'

Byrne said nothing.

'I remember her,' Jessica said. 'I mean, I remember the story. I think my father talked about it. Plus, it was all over the news for a while.' Although she'd been in high school at the time she and her friends had discussed the case, mainly because it involved sex, violence and celebrity.

In November 1990 a woman named Christa-Marie Schönburg, a cellist with the Philadelphia Orchestra, was arrested and charged in the murder of a man named Gabriel Thorne. According to the news reports, Thorne was Christa-Marie's psychiatrist, but there was a great deal of speculation at the time as to whether or not they were romantically involved, even though Thorne had been Christa-Marie's caregiver since she was a child and was three decades her senior. If Jessica remembered correctly, Christa-Marie confessed to second-degree murder, diminished capacity, and was sentenced to twenty-to-life in the women's facility at the State Correctional Institution at Muncy.

'That was your first case?' Jessica asked.

Byrne nodded. 'My first as a lead detective, yeah. I was partnered with Jimmy.'

Jimmy Purify, his rabbi in the homicide unit, had been Byrne's partner before Jessica.

'I don't understand,' Jessica said. 'Is Christa-Marie still in Muncy?'

'No,' Byrne said. 'She was released a few years ago. The last I heard she's still living in the Chestnut Hill house.'

Jessica decided not to ask her partner why he knew all this. It was not all that uncommon for detectives to keep track of people they had arrested and convicted of crimes. What surprised Jessica was that she had known none of this.

'Have you spoken to her since her release?'

'No.'

'Has she tried to contact you before this?'

'Not that I know of.'

Jessica took a few beats. She looked again at the handwriting on the note. It did not look like the penmanship of someone deranged. 'Is she, how do I put this ... better now?'

Byrne shrugged. 'I don't know. The murder was pretty brutal, and she went through a battery of psychological tests at the time of the hearings. I saw some of the reports. Chronic depression. Borderline bipolar. It never came to anything because she pled out. There never was a trial.'

'Were you called at the hearing?'

'I was.'

'Did you testify?'

Byrne hesitated before answering. Jessica sensed a feeling of regret. 'Yes.'

Jessica tried to arrange the timeline in her mind. 'When was that card postmarked?'

Byrne looked at the envelope. 'Last Thursday.'

Jessica did the math. 'So she sent it—'

'Before the murders.'

Jessica felt her breath catch. She tried to process all this. It wasn't often that she was thrown such a curve. 'Is she capable of something like this? I mean, physically capable?'

Jessica knew that at least part of her question was rhetorical. The woman was a convicted murderer, after all. Obviously she was capable of violence. But violence committed in the throes of rage or passion didn't necessarily lead to cold blooded, well-calculated murder. And then there were the physical elements.

'She's capable,' Byrne said. 'The logistics? She's not a big woman, Jess, and she's obviously a lot older now. I don't think she could have done all this without some help.'

Jessica was silent for a moment. 'Okay. Maybe it's just a coincidence. The lion and the rooster and the swan.'

Byrne just glared.

'Okay, it was worth a shot.' Jessica glanced at her watch. 'Do you want to go now or in the morning?'

'Go where?'

'Kevin. We need to talk to her.'

Byrne took the note card from her, slipped it back into the envelope. 'I should probably talk to her alone.'

Byrne was probably right, but that didn't make Jessica want to go along any less. 'You have to tell the boss, Kevin. You have to share it with the team.'

Byrne glanced around the small, cramped room. There wasn't really anything to look at besides a beaten-up coffee maker and the two-way mirror looking into one of the interview rooms. He looked back at his partner.

'Tomorrow,' he said.

Jessica started to object, but Byrne continued.

'Look, this is connected with the Kenneth Beckman case, and I'm working that case. How it's connected, I have no idea. But if it turns out to be something, I'll post it. If it doesn't, then there's no need to drag all this into the mix.'

'How could it not be connected, Kevin? It's not as if Christa-Marie could have just now learned any of this from anyone here. She wrote the note before the murders happened.'

'If I tell Dana right now, what is she going to do? Send a couple of detectives to interrogate Christa-Marie? I know Christa-Marie. I'm the one Dana would send, anyway. There's no reason to turn this woman's life upside down until we know what this is all about.'

'So you're going to talk to her off the record?'

Byrne said nothing.

Jessica wanted to remind her partner that Christa-Marie Schönburg was a confessed murderer, a woman who had spent more than fifteen years in prison. If he didn't have some sort of as-yet-unidentified emotional attachment to the woman and her case, and he'd heard that a confessed murderer had information on fresh homicides, he'd be charging that way with the cavalry and more.

'Besides,' Byrne began, moving on to his closing argument, 'who's to say I didn't read this note tomorrow? Everyone knows I never open my mail.'

Kevin Byrne's secrets were safe with Jessica, as were hers with him. She trusted his judgment more than anyone else she knew.

'Okay,' Jessica said. 'Where do you want me on this?'

'I'll drive up to Chestnut Hill first thing in the morning. I'll call you after.'

Jessica nodded. They both went silent for a long time.

Finally Jessica asked, 'Are you okay, Kevin?'

Byrne opened the door of the coffee room, glanced out. The duty room was a ghost town. He turned back to his partner and said softly: 'I really don't know.'

Twenty minutes later Jessica watched Byrne gather his things, close his briefcase, retrieve his weapon from the file cabinet, grab his coat and keys. He stopped at the door, turned, gave her a sad smile and a wave. As he disappeared around the corner Jessica knew there was something else going on with him, something other than the job, something other than the horror of the four bodies dumped ceremoniously around their city.

Something he wasn't telling her.

Chapter 40

He sits across the table from me, a trembling wreck of a man. In his hands is an old photograph, its colors long faded, its edges folded and creased.

We have had our coffee, shared our pleasantries. I am not one seduced by nostalgia. It means nothing to me.

'I didn't think you were coming back,' he says.

'But you know why I am here,' I say. 'Don't you?'

He nods.

'Everything has changed now,' I say. 'We can never go back.'

He nods again, this time with a tear in his eye.

I glance at my watch. It is time, and time is short. I stand, bring my coffee cup to the sink, rinse it in scalding water. I dry the cup, return it to the cupboard. I am wearing gloves, but one can never be too careful. I return to the table. We fall silent. There is always a calm before the truth.

'Will it hurt?' he asks.

I listen to the voices of the dead swirling around me. I would love to ask them this question. Alas, I cannot. 'I don't know.'

'It's all so Cho Cho San, is it not?'

' Without the baby,' I say.

' Without the baby.'

A few moments pass. Clouds shade his eyes. 'Remember how it was?' he asks.

'I do. All things were possible then, n'est-ce pas.? All futures.'

When I think of those times, I am saddened. I realize how much of it is gone forever, lost in the ductwork of memory. I stand. 'Do you want me to wait?'

He looks at the table for a moment, then at his hands. 'No,' he says softly.

I take the photograph from him, put it into my pocket. At the door I stop, turn. I see myself in the mirror at the end of the hall. It reminds me of the shiny crimson mirror of blood on the floor.

Before leaving I turn up the music. It is not Chopin this time, but rather Hoist's Planets Suite, a movement called 'Venus, The Bringer of Peace'.

Peace.

Sometimes, I think, as I step through the door for the last time, the music exalts the moment.

Sometimes it is the other way around.

Chapter 41

The Penn Sleep Center, part of the University of Pennsylvania Hospital system, was located in a modern steel and glass building on Market Street near 36th.

Byrne crossed the river about six, found a parking space, checked in at the desk, presented his insurance card, sat down, speed-skimmed a copy of Neurology Today, one of his all-time favorite magazines. He covertly checked the handful of people scattered around the waiting room. Not surprisingly, everyone looked exhausted, beat-up, dragged– out. He hoped everyone there was a new patient. He didn't want to think they were on their twentieth appointment and still looked this bad.

'Mr. Byrne?'

Byrne looked up. Standing at the end of the long desk was a blonde woman, no more than five feet tall. She was in her early forties and wore pink-rimmed glasses. She was perky and full of energy. Insomniacs hate perky.

Byrne got up, walked over to the bubbly gal in white rayon.

'Hi!' she chirruped. 'How are you today?'

'Never better, thanks,' Byrne said. Of course, if that was the case, what the hell was he doing at the hospital? 'How about yourself?'

'Super!' she replied.

Her name tag read Viv. Probably short for Vivacious.

'We're just going to check your height and weight.' She led him over to the digital scale, instructed him to take off his shoes. He stepped on the scale.

'I don't want to know how much I weigh, okay?' Byrne said. 'Lately I've just been ... I don't know. It's hormonal, I think.'

Viv smiled, zipped her lips in a dramatic gesture, recorded Byrne's weight without a word. 'Now, if you could turn around, we'll check your height.'

Byrne spun around. Viv stepped on a footstool, raised the bar of the stadiometer, then lowered it gently, touching the top of Byrne's head. 'What about height?' she asked. 'Would you like to know how tall you are?'

'I think I can handle my height. Emotionally speaking.'

'You're still six foot, three inches.'

'Good,' Byrne said. 'So I haven't shrunk.'

'Nope. You must be washing in cold water.'

Byrne smiled. He liked Viv, despite her vim.

'Come this way,' she said.

In the small, windowless examining room Byrne cruised the two battered magazines, picking up a dozen new 30-minute chicken recipes, along with some tips on how to get puppy stains out of the upholstery.

A few minutes later the doctor came in. She was Asian, about thirty, quite attractive. Pinned to her lab coat was a photo ID. Her name was Michelle Chu.

They got the pleasantries about the weather and the insanity of the people in the indoor parking garage out of the way. Dr. Chu ran through Byrne's history on the computer's LCD monitor. When she had him sufficiently pegged, she turned in her chair, crossed her legs.

'So, how long have you had insomnia?'

'Let me put it this way,' Byrne said. 'It's been so long that I can't remember.'

'Do you have trouble falling asleep or staying asleep?'

'Both.'

'How long, on average, does it take you to fall asleep?'

All night, Byrne thought. But he knew what she meant. 'Maybe an hour.'

'Do you wake up during the night?'

'Yeah. At least a couple of times.'

The doctor made a few more notes, her fingers racing across the keyboard. 'Do you snore?'

Byrne knew the answer to this. He just didn't want to tell her how he knew. 'Well, these days I don't really have a steady...'

'Bed partner?'

'Yeah,' Byrne said. 'That. Do you think you could write me a prescription for one of those?'

She laughed. 'I could, but I don't think your insurance provider would cover it.'

'You're probably right,' Byrne said. 'I can barely get them to pay for the Ambien.'

Ambien. The magic drug, the magic word. At least around neurologists. He had her attention now.

'How long have you been taking Ambien?'

'On and off for as long as I can remember.'

'Do you think you've developed a dependence?'

'Without question.'

Dr. Chu handed him a pre-printed sheet. 'These are some of the sleep-hygiene suggestions we have—'

Byrne held up a hand. 'May I?'

'Absolutely.'

'No alcohol, caffeine, or high-fat foods late at night. No nicotine. Exercise regularly, but not within four hours of bedtime. Go to bed and get out of bed at the same times every day. Turn your alarm clock around so you can't see the time. Keep your bedroom cool, not cold. If you can't fall asleep in ten minutes or so, get out of bed until you feel tired again. Although, if you can't see your clock, I don't know how you're supposed to know it's been ten minutes.'

Dr. Chu stared at him for a few moments. She had stopped typing altogether. 'You seem to know quite a bit about this.'

Byrne shrugged. 'You do something long enough.'

She then typed for a full minute. Byrne just watched. When she was done she said, 'Okay. Hop up on the table, please.'

Byrne stood up, walked over to the paper-lined examining table, slid onto it. He hadn't hopped anywhere in years, if ever. Dr. Chu looked into his eyes, ears, nose, throat. She listened to his heart, lungs. Then she took out a tape measure, measured his neck.

'Hmm,' she said.

Never a good sign. 'I prefer a spread collar,' Byrne said. 'French cuffs.'

'Your neck's circumference is greater than seventeen inches.'

'I work out.'

She sat down, put her stethoscope around her neck. Her face took on a concerned look. Not the you are in deep shit look, but concerned. 'You have a few markers for sleep apnea.'

Byrne had heard of it, but he really didn't know anything about it. The doctor explained that apnea was a condition wherein a person stops breathing during the night.

'I stop breathing?'

'Well, we don't know that for sure yet.'

'I'm kind of in the stop-breathing business, you know.'

The doctor smiled. 'This is a little different. I think I should schedule you for a sleep study.' She handed him a brochure. Color pics of smiling, healthy people who looked like they got a lot of sleep.

'Okay.'

'You're willing to give it a shot?'

Anything was better than what he was going through. Except maybe the business about not breathing. 'Sure. I'm in.'

In the waiting room, three of the five people were asleep.

Byrne stopped at the American Pub in the Center Square Building on Market Street. The place was lively, and lively was just what was needed. He staked a place at the end of the bar, nursed a Bushmills. At just after ten o'clock his phone rang. He checked the ID, fully prepared to blow it off. It was a 215 exchange, with a familiar prefix. A PPD number. He had to answer.

'This is Kevin.'

'Detective Byrne?'

It was a woman's voice. A young woman's voice. He did not recognize it. 'Yes?'

'It's Lucy.'

It took Byrne a little while to realize who it was. Then he remembered. 'Hi, Lucy. Is something wrong?'

'I need to talk to you.'

'Where are you? I'll come get you.'

A long pause.

'Lucy?'

'I'm in jail.'

The Mini-Station was located on South Street between Ninth and Tenth. Originally activated in 1985 to provide weekend coverage from spring to autumn, addressing the issues generated by crowds gravitating to South Street for its clubs, shopping and restaurants, it had since become a seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day, year-round commitment, expanded to cover the entire corridor, which included more than 400 retail premises and nearly eighty establishments with liquor licenses.

When Byrne walked in, he immediately spotted an old comrade, P/O Denny Dorgan. Short and brick-solid, Dorgan, who was now in his early forties, still worked the bike patrol.

'Alert the hounds,' Dorgan said. 'We got royalty in the building.'

They shook hands. 'You getting shorter and uglier?' Byrne asked.

'Yeah. It's the supplements my wife is making me take. She thinks it will keep me from straying. Shows you what she knows.'

Byrne glanced over at Dorgan's bike, leaning near the front door. 'Good thing you can get heavy-duty shocks on the thing.'

Dorgan laughed, turned and looked at the waif-like girl sitting on the bench behind him. He turned back. 'Friend of yours?'

Byrne looked over at Lucy Doucette. She looked like a lost little kid.

'Yeah,' Byrne said. 'Thanks.'

Byrne wondered what Dorgan wondered, whether he thought that Byrne was dallying with a nineteen-year-old. Byrne had long ago stopped being concerned with what people thought. What had happened here was clear. Dorgan had stepped in between a misdemeanor and the law, on Byrne's behalf, and had done it as a favor to a fellow cop. The gesture would go into the books as a small act of kindness, and would one day be repaid. No more, no less. Everything else was squad-car scandal.

Byrne and Lucy had coffee at a small restaurant on South Street. Lucy told him the story. Or, it seemed to Byrne, the part she could bring herself to tell. She had been detained by security personnel at a kids'-clothing boutique on South. They said she'd attempted to walk out of the store with a pair of children's sweaters. The electronic security tags had been removed and were found underneath one of the sale racks, but Lucy had been observed walking around with the items, items which had not been returned to the racks. She had no sales receipts on her. Lucy had not resisted in the least.

'Did you mean to walk out with these items?'

Lucy buried her face in her hands for a moment. 'Yes. I was stealing them.'

From most people Byrne would have expected vehement denials, tales of mistaken identity and dastardly set-ups. Not Lucy Doucette. He remembered her as a blunt and honest person. Well, she was not that honest, apparently.

'I don't understand,' Byrne said. 'Do you have a child? A niece or a nephew that these sweaters were for?'

'No.'

'A friend's child?'

Lucy shrugged. 'Not exactly.'

Byrne watched her, waiting for more.

'It's complicated,' she finally said.

'Do you want to tell me about it?'

Lucy took another second. 'Do I have to tell you now?'

Byrne smiled. 'No.'

The waitress refilled their cups. Byrne considered the young woman in front of him. He remembered how she had appeared in their therapy group. Shy, reluctant, scared. Not much had changed.