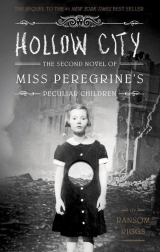

Текст книги "Hollow City"

Автор книги: Ransom Riggs

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

* * *

We hurried past the ruined blocks as quickly as we could, then marveled as the streets returned to life around us. Just a short walk from Hell, people were going about their business, striding down sidewalks, living in buildings that still had electricity and windows and walls. Then we rounded a corner and the cathedral’s dome revealed itself, proud and imposing despite patches of fire-blackened stone and a few crumbling arches. Like the spirit of the city itself, it would take more than a few bombs to topple St. Paul’s.

Our hunt began in a square close to the cathedral, where old men on benches were feeding pigeons. At first it was mayhem: we bounded in, grabbing wildly as the pigeons took off. The old men grumbled, and we withdrew to wait for their return. They did, eventually, pigeons not being the smartest animals on the planet, at which point we all took turns wading casually into the flock and trying to catch them by surprise, reaching down to snatch at them. I thought Olive, who was small and quick, or Hugh, with his peculiar connection to another sort of winged creature, might have some luck, but both were humiliated. Millard didn’t fare any better, and they couldn’t even see him. By the time my turn came, the pigeons must’ve been sick of us bothering them, because the moment I strolled into the square they all burst into flight and took one big, simultaneous cluster-bomb crap, which sent me flailing toward a water fountain to wash my whole head.

In the end, it was Horace who caught one. He sat down next to the old men, dropping seeds until the birds circled him. Then, leaning slowly forward, he stretched out his arm and, calm as could be, snagged one by its feet.

“Got you!” he cried.

The bird flapped and tried to get away, but Horace held on tight.

He brought it to us. “How can we tell if it’s peculiar?” he said, flipping the bird over to inspect its bottom, as if expecting to find a label there.

“Show it to Miss Peregrine,” Emma said. “She’ll know.”

So we opened Bronwyn’s trunk, shoved the pigeon inside with Miss Peregrine, and slammed down the lid. The pigeon screeched like it was being torn apart.

I winced and shouted, “Go easy, Miss P!”

When Bronwyn opened the trunk again, a poof of pigeon feathers fluttered into the air, but the pigeon itself was nowhere to be seen.

“Oh, no—she’s ate it!” cried Bronwyn.

“No she hasn’t,” said Emma. “Look beneath her!”

Miss Peregrine lifted up and stepped aside, and there underneath her was the pigeon, alive but dazed.

“Well?” said Enoch. “Is it or isn’t it one of Miss Wren’s?”

Miss Peregrine nudged the bird with her beak and it flew away. Then she leapt out of the trunk, hobbled into the square, and with one loud squawk scattered the rest of the pigeons. Her message was clear: not only was Horace’s pigeon not peculiar, none of them were. We’d have to keep looking.

Miss Peregrine hopped toward the cathedral and flapped her wing impatiently. We caught up to her on the cathedral steps. The building loomed above us, soaring bell towers framing its giant dome. An army of soot-stained angels glared down at us from marble reliefs.

“How are we ever going to search this whole place?” I wondered aloud.

“One room at a time,” Emma said.

A strange noise stopped us at the door. It sounded like a faraway car alarm, the note pitching up and down in long, slow arcs. But there were no car alarms in 1940, of course. It was an air-raid siren.

Horace cringed. “The Germans are coming!” he cried. “Death from the skies!”

“We don’t know what it means,” Emma said. “Could be a false alarm, or a test.”

But the streets and the square were emptying fast; the old men were folding up their newspapers and vacating their benches.

“They don’t seem to think it’s a test,” Horace said.

“Since when are we afraid of a few bombs?” Enoch said. “Quit talking like a Nancy Normal!”

“Need I remind you,” said Millard, “these are not the sort of bombs we’re accustomed to. Unlike the ones that fall on Cairnholm, we don’t know where they’re going to land!”

“All the more reason to get what we came for, and quickly!” Emma said, and she led us inside.

* * *

The cathedral’s interior was massive—it seemed, impossibly, even larger than the outside—and though damaged, a few hardy believers knelt here and there in silent prayer. The altar was buried under a midden of debris. Where a bomb had pierced the roof, sunlight fell down in broad beams. A lone soldier sat on a fallen pillar, gazing at the sky through the broken ceiling.

We wandered, necks craned, bits of concrete and broken tile crunching beneath our feet.

“I don’t see anything,” Horace complained. “There are enough hiding places here for ten thousand pigeons!”

“Don’t look,” Hugh said. “Listen.”

We stopped, straining to hear the telltale coo of pigeons. But there was only the ceaseless whine of air-raid sirens, and below that a series of dull cracks like rolling thunder. I told myself to stay calm, but my heart thrummed like a drum machine.

Bombs were falling.

“We need to go,” I said, panic choking me. “There has to be a shelter nearby. Somewhere safe we can hide.”

“But we’re so close!” said Bronwyn. “We can’t quit now!”

There was another crack, closer this time, and the others started to get nervous, too.

“Maybe Jacob’s right,” said Horace. “Let’s find somewhere safe to hide until the bombing’s through. We can search more when it’s over.”

“Nowhere is truly safe,” said Enoch. “Those bombs can penetrate even a deep shelter.”

“They can’t penetrate a loop,” Emma said. “And if there’s a tale about this cathedral, there’s probably a loop entrance here, too.”

“Perhaps,” said Millard, “perhaps, perhaps. Hand me the book and I shall investigate.”

Bronwyn opened her trunk and handed Millard the book.

“Let me see now,” he said, turning its pages until he reached “The Pigeons of St. Paul’s.”

Bombs are falling and we’re reading stories, I thought. I have entered the realm of the insane.

“Listen closely!” Millard said. “If there’s a loop entrance nearby, this tale may tell us how to find it. It’s a short one, luckily.”

A bomb fell outside. The floor shook and plaster rained from the ceiling. I clenched my teeth and tried to focus on my breathing.

Unfazed, Millard cleared his throat. “The Pigeons of St. Paul’s!” he began, reading in a big, booming voice.

“We know the title already!” said Enoch.

“Read faster, please!” said Bronwyn.

“If you don’t stop interrupting me, we’ll be here all night,” said Millard, and then he continued.

“Once upon a peculiar time, long before there were towers or steeples or any tall buildings at all in the city of London, there was a flock of pigeons who got it into their minds that they wanted a nice, high place to roost, above the bustle and fracas of human society. They knew just how to build it, too, because pigeons are builders by nature, and much more intelligent than we give them credit for being. But the people of ancient London weren’t interested in constructing tall things, so one night the pigeons snuck into the bedroom of the most industrious human they could find and whispered into his ear the plans for a magnificent tower.

“In the morning, the man awoke in great excitement. He had dreamed—or so he thought—of a magnificent church with a great, reaching spire that would rise from the city’s tallest hill. A few years later, at enormous cost to the humans, it was built. It was a very towering sort of tower and had all manner of nooks and crannies inside it where the pigeons could roost, and they were very satisfied with themselves.

“Then one day Vikings sacked the city and burned the tower to the ground, so the pigeons had to find another architect, whisper in his ear, and wait patiently for a new church tower to be built—this one even grander and taller than the first. And it was built, and it was very grand and very tall. And then it burned, too.

“Things went on in this fashion for hundreds of years, the towers burning and the pigeons whispering plans for still grander and taller towers to successive generations of nocturnally inspired architects. Though these architects never realized the debt they owed the birds, they still regarded them with tenderness, and allowed them to hang about wherever they liked, in the naves and belfries, like the mascots and guardians of the place they truly were.”

“This is not helpful,” Enoch said. “Get to the loop entrance part!”

“I am getting to what I am getting to!” Millard snapped.

“Eventually, after many church towers had come and gone, the pigeons’ plans became so ambitious that it took an exceedingly long time to find a human intelligent enough to carry them out. When they finally did, the man resisted, believing the hill to be cursed, so many churches having burned there in the past. Though he tried to put the idea out of his mind, the pigeons kept returning, night after night, to whisper it in his ear. Still, the man would not act. So they came to him during the day, which they had never done before, and told him in their strange laughing language that he was the only human capable of constructing their tower, and he simply had to do it. But he refused and chased them from his house, shouting, ‘Shoo, begone with ye, filthy creatures!’

“The pigeons, insulted and vengeful, hounded the man until he was nearly mad—following him wherever he went, picking at his clothes, pulling his hair, fouling his food with their hind-feathers, tapping on his windows at night so he couldn’t sleep—until one day he fell to his knees and cried, ‘O pigeons! I will build whatever you ask, so long as you watch over it and preserve it from the fire’

“The pigeons puzzled over this. Consulting among themselves, they decided that they might’ve been better guardians of past towers if they hadn’t come to enjoy building them so much, and vowed to do everything they could to protect them in the future. So the man built it, a soaring cathedral with two towers and a dome. It was so grand, and both the man and the pigeons were so pleased with what they’d made that they became great friends; the man never went anywhere for the rest of his life without a pigeon close at hand to advise him. Even after he died at a ripe and happy old age, the birds still went to visit him, now and again, in the land below. And to this very day, you’ll find the cathedral they built standing on the tallest hill in London, the pigeons watching over it.” Millard closed the book. “The end.”

Emma made an exasperated noise. “Yes, but watching over it from where?”

“That could not have been less helpful to our present situation,” said Enoch, “were it a story about cats on the moon.”

“I can’t make heads or tails of it,” said Bronwyn. “Can anyone?”

I nearly could—felt close to something in that line about “the land below”—but all I could think was, The pigeons are in Hell?

Then another bomb fell, shaking the whole building, and from high overhead came a sudden flutter of wingbeats. We looked up to see three frightened pigeons shoot out of some hiding place in the rafters. Miss Peregrine squawked with excitement—as if to say, That’s them!—and Bronwyn scooped her up and we all went racing after the birds. They flew down the length of the nave, turned sharply, and disappeared through a doorway.

We reached the doorway a few seconds later. To my relief, it didn’t lead outside, where we’d never have a hope of catching them, but to a stairwell, down a set of spiral steps.

“Hah!” Enoch said, clapping his pudgy hands. “They’ve gone and done it now—trapped themselves in the basement!”

We sprinted down the stairs. At the bottom was a large, dimly lit room walled and floored with stone. It was cold and damp and almost completely dark, the electricity having been knocked out, so Emma sparked a flame in her hand and shone it around, until the nature of the space became apparent. Beneath our feet, stretching from wall to wall, were marble slabs chiseled with writing. The one below me read:

B

ISHOP

E

LDRIDGE

T

HORNBRUSH, DYED ANNO 1721

“This is no basement,” Emma said. “It’s a crypt.”

A little chill came over me, and I stepped closer to the light and warmth of Emma’s flame.

“You mean, there are people buried in the floor?” said Olive, her voice quavering.

“What of it?” said Enoch. “Let’s catch a damned pigeon before one of those bombs buries us in the floor.”

Emma turned in a circle, throwing light on the walls. “They’ve got to be down here somewhere. There’s no way out but that staircase.”

Then we heard a wing flap. I tensed. Emma brightened her flame and aimed it toward the sound. Her flickering light fell on a flat-topped tomb that rose a few feet from the floor. Between the tomb and the wall was a gap we couldn’t see behind from where we stood; a perfect hiding spot for a bird.

Emma raised a finger to her lips and motioned for us to follow. We crept across the room. Nearing the tomb, we spread out, surrounding it on three sides.

Ready? Emma mouthed.

The others nodded. I gave a thumbs-up. Emma tiptoed forward to peek behind the tomb—and then her face fell. “Nothing!” she said, kicking the floor in frustration.

“I don’t understand!” said Enoch. “They were right here!”

We all came forward to look. Then Millard said, “Emma! Shine your light on top of the tomb, please!”

She did, and Millard read the tomb’s inscription aloud:

H

ERE LIETH

S

IR

C

HRISTOPHER

W

REN

B

UILDER OF

T

HIS

C

ATHEDRAL

“Wren!” Emma exclaimed. “What an odd coincidence!”

“I hardly think it’s a coincidence,” said Millard. “He must be related to Miss Wren. Perhaps he’s her father!”

“That’s very interesting,” said Enoch, “but how does that help us find her, or her pigeons?”

“That is what I am attempting to puzzle out.” Millard hummed to himself and paced a little and recited a line from the tale: “the birds still went to visit him, now and again, in the land below.”

Then I thought I heard a pigeon coo. “Shh!” I said, and made everyone listen. It came again a few seconds later, from the rear corner of the tomb. I circled around it and knelt down, and that’s when I noticed a small hole in the floor at the tomb’s base, no bigger than a fist—just large enough for a bird to wriggle through.

“Over here!” I said.

“Well, I’ll be stuffed!” said Emma, holding her flame up to the hole. “Perhaps that’s ‘the land below’?”

“But the hole is so small,” said Olive. “How are we supposed to get the birds out of there?”

“We could wait for them to leave,” said Horace, and then a bomb fell so close by that my eyes blurred and my teeth rattled.

“No need for that!” said Millard. “Bronwyn, would you please open Sir Wren’s tomb?”

“No!” cried Olive. “I don’t want to see his rotten old bones!”

“Don’t worry, love,” Bronwyn said, “Millard knows what he’s doing.” She planted her hands on the edge of the tomb lid and began to push, and it slid open with a slow, grating rumble.

The smell that came up wasn’t what I’d expected—not of death, but mold and old dirt. We gathered around to look inside.

“Well, I’ll be stuffed,” Emma said.

Where a coffin should’ve been, there was a ladder, leading down into darkness. We peered into the open tomb.

“There’s no way I’m climbing down there!” Horace said. But then a trio of bombs shook the building, raining chips of concrete on our heads, and suddenly Horace was pushing past me, grasping for the ladder. “Excuse me, out of my way, best-dressed go first!”

Emma caught him by the sleeve. “I have the light, so I’ll go first. Then Jacob will follow, in case there are … things down there.”

I flashed a weak smile, my knees going wobbly at the thought.

Enoch said, “You mean things other than rats and cholera and whatever sorts of mad trolls live beneath crypts?”

“It doesn’t matter what’s down there,” Millard said grimly.

“We’ll have to face it, and that’s that.”

“Fine,” said Enoch. “But Miss Wren had better be down there, too, because rat bites don’t heal quickly.”

“Hollowgast bites even less so,” said Emma, and then she swung her foot onto the ladder.

“Be careful,” I said. “I’ll be right above you.”

She saluted me with her flaming hand. “Once more into the breach,” she said, and began to climb down.

Then it was my turn.

“Do you ever find yourself climbing into an open grave during a bombing raid,” I said, “and just wish you’d stayed in bed?”

Enoch kicked my shoe. “Quit stalling.”

I grabbed the lip of the tomb and put my foot on the ladder.

Thought briefly of all the pleasant, boring things I might’ve been doing with my summer, had my life gone differently. Tennis camp. Sailing lessons. Stocking shelves. And then, through some Herculean effort of will, I made myself climb.

The ladder descended into a tunnel. The tunnel dead-ended to one side, and in the other direction disappeared into blackness. The air was cold and suffused with a strange odor, like clothes left to rot in a flooded basement. The rough stone walls beaded and dripped with moisture of mysterious origin.

As Emma and I waited for everyone to climb down, the cold crept into me, degree by degree. The others felt it, too. When Bronwyn reached the bottom, she opened her trunk and handed out the peculiar sheep’s wool sweaters we’d been given in the menagerie. I slipped one over my head. It fit me like a sack, the sleeves falling past my fingers and the bottom sagging halfway to my knees, but at least it was warm.

Bronwyn’s trunk was empty now and she left it behind. Miss Peregrine rode inside her coat, where she’d practically made a nest for herself. Millard insisted on carrying the Tales in his arms, heavy and bulky as it was, because he might need to refer to it at any moment, he said. I think it had become his security blanket, though, and he thought of it as a book of spells which only he knew how to read.

We were an odd bunch.

I shuffled forward to feel for hollows in the dark. This time, I got a new kind of twinge in my gut, ever so faint, as if a hollow had been here and gone, and I was sensing its residue. I didn’t mention it, though; there was no reason to alarm everyone unnecessarily.

We walked. The sound of our feet slapping the wet bricks echoed endlessly up and down the passage. There’d be no sneaking up on whatever was waiting for us.

Every so often, from up ahead, we’d hear a flap of wings or a pigeon’s warble, and we’d pick up our pace a little. I got the uneasy feeling we were being led toward some nasty surprise. Embedded in the walls were stone slabs like the ones we’d seen in the crypt, but older, the writing mostly worn away. Then we passed a coffin, grave-less, on the floor—then a whole stack of them, leaned against a wall like discarded moving boxes.

“What is this place?” Hugh whispered.

“Graveyard overflow,” said Enoch. “When they need to make room for new customers, they dig up the old ones and stick them down here.”

“What a terrible loop entrance,” I said. “Imagine walking through here every time you needed in or out!”

“It’s not so different from our cairn tunnel,” Millard said.

“Unpleasant loop entrances serve a purpose—normals tend to avoid them, so we peculiars have them all to ourselves.”

So rational. So wise. All I could think was, There are dead people everywhere and they’re all rotted and bony and dead and, oh God …

“Uh-oh,” Emma said, and she stopped suddenly, causing me to run into her and everyone else to pile up behind me.

She held her flame to one side, revealing a curved door in the wall. It hung open slightly, but only darkness showed through the crack.

We listened. For a long moment there was no sound but our breath and the distant drip of water. Then we heard a noise, but not the kind we were expecting—not a wing-flap or the scratch of a bird’s feet—but something human.

Very softly, someone was crying.

“Hello?” called Emma. “Who’s in there?”

“Please don’t hurt me,” came an echoing voice.

Or was it a pair of voices?

Emma brightened her flame. Bronwyn crept forward and nudged the door with her foot. It swung open to expose a small chamber filled with bones. Femurs, shinbones, skulls—the dismembered fossils of many hundreds of people, heaped up in no apparent order.

I stumbled backward, dizzy with shock.

“Hello?” Emma said. “Who said that? Show yourself!”

At first I couldn’t see anything in there but bones, but then I heard a sniffle and followed the sound to the top of the pile, where two pairs of eyes blinked at us from the murky shadows at the rear of the chamber.

“There’s no one here,” said a small voice.

“Go away,” came a second voice. “We’re dead.”

“No you’re not,” said Enoch, “and I would know!”

“Come out of there,” Emma said gently. “We’re not going to hurt you.”

Both voices said at once: “Promise?”

“We promise,” said Emma.

The bones began to shift. A skull dislodged from the pile and clattered to the floor, where it rolled to a stop at my feet and stared up at me.

Hello, future, I thought.

Then two young boys crawled into the light, on hands and knees atop the bone pile. Their skin was deathly pale and they peeped at us with black-circled eyes that wheeled dizzyingly in their sockets.

“I’m Emma, this is Jacob, and these are our friends,” Emma said. “We’re peculiar and we’re not going to hurt you.”

The boys crouched like frightened animals, saying nothing, eyes spinning, seeming to look everywhere and nowhere.

“What’s wrong with them?” Olive whispered.

Bronwyn hushed her. “Don’t be rude.”

“Can you tell me your names?” Emma said, her voice coaxing and gentle.

“I am Joel and Peter,” the larger boy said.

“Which are you?” Emma said. “Joel or Peter?”

“I am Peter and Joel,” said the smaller boy.

“We don’t have time for games,” said Enoch. “Are there any birds in there with you? Have you seen any fly past?”