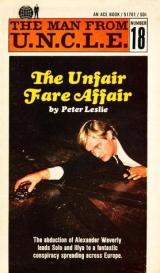

Текст книги "The Unfair Fare Affair "

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

"Hello?" he said. "Hello... Kuryakin to Solo. Channel open. Kuryakin to Solo. Channel open. Kuryakin to Solo—come in, please…"

Chapter 12

The Advance Of Napoleon

"THANK GOD you've come in," Solo said. "I was beginning to get worried!" He rolled over in bed, holding the transceiver above the sheets, and switched on the lamp standing on the bedside table. The hands of the travel clock beside it pointed to three-twenty-two.

"Listen, Napoleon," Kuryakin's voice came faintly from the miniature speaker. "I may have to cut out at any moment. Do you read me?"

"I read you," Solo said. He turned off the light and snuggled down into the bed again, taking the transceiver below the covers. "You are aware that it's between three and four A.M., I suppose?"

"I haven't time to joke, Napoleon."

"Then why call me at this hour, for heaven's sake? Not that it isn't good to hear your Slavic voice."

A chuckle floated from the baton. "I'm sorry about that. This is the first chance I have had. Listen—I've made contact. They've taken me on."

"What! But that's great, Illya—that's fine!" Solo was siting up again, reaching for a pencil and a notepad, feeling for the light.

"I'm being taken to Zurich. At the moment I'm in a small truck somewhere near the Austro-Czech border. We're heading for Linz."

"Have you come all the way in the truck?"

"No. I started out from Prague in a furniture van. With furniture."

"Okay. Seen much of the organization?"

"A girl in Prague. The driver of this truck. That's all."

"Never mind. It's a start. I'll contact Waverly and tell him. In the meantime, I'll try to join up with you, okay?"

"Yes, I think that would be best, Napoleon. If we could work it so that I was on the inside, as it were, and you were nearby, on the outside...

"We'd stand some chance of getting the complete low down on the setup? I agree. Look—when will you arrive in Zurich? Tomorrow afternoon?"

"I should think so. We have three frontiers to cross—the Austro-Czech, the Austro-German and the German-Swiss. And don't forget that I am supposed to be an escaped murderer; so in my adopted role all three should prove equally difficult. The people taking me, that is to say, do not only have to be careful getting me through the so called Iron Curtain."

"I see what you mean," Solo said. "Tell you what, Illya– I'll grab a rented car at dawn and come to meet you."

"How will you know where I am? I mean, we're supposed to be heading for Zurich, but all kinds of things could—"

"Sure, I know. I'll head generally east and south, but we'll keep in touch on the transceivers. I've got a DF/7 with me, so I can get a fix on your position every time we speak. That way I can keep a constant check on your whereabouts."

"Very well, Napoleon. You'd better call me at fixed… No! On second thought, you'd better not call me at all. The transceiver might bleep at an awkward moment."

"Like when you were crossing a frontier? You could always hand the thing to the customs man and say, 'It's for you!'... No, I see the point, though. Okay, we'll do the don't-call-us-we'll-call-you bit. When do you want me to stand by for your calls?"

"Every three hours, I should think. Starting between ten and eleven. Then between one and two, and so on. If I miss out on one, listen for me at the next. Right?"

"Right, Colonel!"

"And Napoleon—don't forget to make with the fixes, eh? As an illegal—er—cargo, I may have to travel most of the way cooped up somewhere. And I may not know within hundreds of miles where I am."

"Okay," Solo said. "Take it easy, boy."

"I think I must go now, Napoleon. We are slowing down. It may be because the frontier is near."

"Off you go, then. Let the Don flow quiet to the sea."

"What was that?"

"A quotation. Let it pass. It means 'I'll be listening at ten.'"

Solo went back to sleep until six o'clock. At eight, having showered, shaved, checked out of the hotel, and hired a car, he was on the Sint Pietersstraat.

Hendrik van der Lee was already at work, covering a huge sheet of paper with hieroglyphics as he held the telephone clamped to one ear. He waved Solo to a seat and went on talking.

"… from the Rembrandtsplein, did you say? And then out on the Arnhem motor road?... Yes, of course. But look, boy, we have to make sure... Very well, then; you do that. But remember you have to have witnesses who saw her leave... Sure I will, then. But first see what the chambermaid has to say, eh?..."

Eventually he replaced the instrument on its cradle and turned to Solo with a crooked smile. "Hello, you," he said. "You wouldn't believe the trouble we have. There's this little fellow, a military attaché of one of the Latin American countries. They want the lowdown on his private life—but, sure, the man's so active; moving from girl to girl from place to place so fast that my people cannot tell whether it's a miss or a missile he's after!"

"My heart bleeds for you," Solo said. "Can I please use your shortwave transmitter again to call Waverly?"

"You can that. Though it'll be a rare shock to the dear fellow, I doubt not."

Solo shook his head. It would be just after two in the morning in New York. "Waverly never goes to bed before half-past one or two," he said. "With luck I'll get him before he's got his head down for the night!"

"Well, ask the lad how things are, for me," Van der Lee said, "for I've had no word from him for many a long month."

"Oh, come now! That's enough of your Celtic hyperbole!" Solo chided. "It can't be more than a week since you were in touch with him."

"What are you talkin' about?"

"Well, he must have been in contact to arrange about our meeting."

"Our meeting? I don't follow you at all." The Irishman was staring.

"You mean he didn't? You weren't tipped off I was coming?"

Van der Lee shook his head.

"You hadn't come to the Terminus especially to contact me? Our meeting was a coincidence? But that's fantastic! I never thought of asking…"

And a few minutes later, when Waverly's irascible voice was crackling over the ether, Solo asked, "How come you hadn't warned Tufik—Van der Lee, I should say—that I was coming? I mean, after I had received the tickets and room reservation you sent, I naturally expected to meet someone, either here or on the journey. But weren't you leaving it a bit vague if you—"

"Tickets?" Waverly's voice interrupted. "Reservation? Have you taken leave of your senses, Mr. Solo? I have made no communication with you since you left."

Solo whistled softly. If neither Waverly nor Van der Lee knew anything about that special-delivery letter with the tickets in it, then it meant he had deliberately been decoyed to the hotel! Which in turn meant that someone—the person who had tried to run him down in Paris, presumably—had changed his mind and decided to attend to him in Holland.

But why?

If they were going to shoot at him when he was on a balcony or knock him on the head and abduct him from a hotel room, why did this have to be done in The Hague? After all, there were plenty of balconies and plenty of hotel rooms, in Europe!

There could be only one answer—because the person of persons who had to do the shooting and abducting found it convenient. And in practice, surely, this must mean that they had to be in The Hague; they were unable to leave the city... and so, having failed in Paris, they arranged for Solo to come where they were.

The instigators of both decoy and attempted kidnapping, it seemed obvious, must be the men behind the escape network; they had somehow found out that somebody was asking too many questions and they had tried to remove him.

The realization didn't get Solo much further forward. He had asked a lot of questions in a lot of places. Many of the people he had questioned had themselves demanded information of others—who had in their turn probably talked. And the people who were after him could have found out from any of them; he had no means of knowing where the leak had occurred. His discovery that he had been duped therefore gave him no pointers from which he could deduce anything about the network or its operators.

It had, on the other hand, even if coincidentally, brought him into contact with Van der Lee. And it had made him realize that he might have misjudged the girl Annike, in thinking her a party to the kidnapping!

When he had spoken to Waverly the previous night, it had been mainly to hear about Illya Kuryakin's visit to Prague and the reason for it. He had said little about his own researches. He filled in the details of these now, and as soon as Waverly had signed off, he turned back to the fat man in the wheelchair and said, "There's the sum total of my investigations to date! About the only positive thing about them is that I know now that—at least mentally—I owe your little girl an apology."

"My little girl?"

"Annike. She is still with you, isn't she? I'm afraid I'd been thinking she was responsible for my being knocked on the head. I figured she'd engineered my return to the Terminus and suggested I needed a coat simply because she knew there was somebody up in my room waiting to sap me."

"Well now," Van der Lee said, "I don't know about that at all. But Annike herself is away for a couple of days, Mr. Solo. She had two owin' from the bank holiday period, and she asked could she take them now. She'll not be back until the day after tomorrow, I'm afraid. Can I give her a message?"

Solo shook his head. "I guess not. You don't know where she went, do you? I kind of like making apologies to blondes!"

"Ah, no. That I don't. Her time's her own when she's away out of this."

The agent sighed. "Okay then. I'll be on my way… unless you have any second thoughts about that information I wanted to buy from you?"

It was the fat man's turn to shake a massive head. His jowls quivered in negation as he said regretfully, "A rule's a rule, Mr. Solo. Even among friends. Anyway, I doubt if it would be much use to you if I could talk—a name, a description, a probability of whereabouts. Which you'll latch on to soon enough yourself if Mr. Kuryakin's lucky. You already know they were asking about you... and you've had proof of why! That's all, I guess."

Solo shook hands. "I'll get along then. And thanks anyway."

"A pleasure, Mr. Solo. Always a pleasure. And one thing. Wait'll I tell you: remember—it's not always the new ones that travel the best..."

"Not always the new ones...?" echoed Solo with a puzzled frown.

But the Moroccan-Irishman refused to elaborate his hint–if hint it was—and Napoleon Solo went his way with the riddle unsolved, leaving the man in the wheelchair smiling blandly as he pulled a huge pile of daily newspapers toward him and reached into his pocket for a fistful of different colored pens.

Solo had rented a Citroën DS21, a splendid car for covering a lot of ground quickly. Having skirted Antwerp and Brussels, he managed to make the gray, cobbled central place of Namur in time to buy beer and charcuterie and bread before the stores closed for lunch.

Then, taking advantage of the midday traffic lull, he drove rapidly across the ragged, untidy Belgian plain, with it dull and grimy little towns, until he reached the Ardennes. Shortly before two o'clock, he pulled off the road not far from Bastogne and prepared to eat. Around him, the undulating country fell away in a series of interlocking wooded curves. And over all these acres of trunk and branch and dead leaf, the sky—which had been becoming more and more overcast since early morning—stretched a sullen yellow canopy.

Wind moaned in the pines above Solo's head and stirred the needles around the boles of the trees further down the hill. It looked as though it was going to snow.

He sat for a while with the engine running and the heater on, waiting for Illya's call to come through on the transceiver.

They had had time only to exchange a few words on the ten o'clock transmission—Solo had been parked behind a highway café where he had stopped for coffee—before Kuryakin had been forced to hide the baton because his chauffeur was coming around to talk to him. From the fix Solo had been able to take from the small but sophisticated machine he carried in his valise, he judged the Russian to have been somewhere between Wels and Gmunden, in Austria.

When he came through again at one minute to two, he told Solo that they had made very little progress during the day. Apparently the network preferred to travel mainly at night. He had been in the back of an empty cattle truck, a hearse, and a trailer truck since they had abandoned the electrical delivery truck near Linz hours before. He had no idea where they were now.

Solo made it somewhere near the Alter See, a few miles from Salzburg.

He finished his lunch and drove on into Luxembourg. On the eastern slopes of the Ardennes, snow had already fallen. There was a thin coating beneath the trees, and occasionally, along the surface of the twisty road near Esch-sur-Sure, powdery white trails snaked toward him in the wind. Farther south in the Grand Duchy, the fall had been heavier. Snow lay thickly on branches and roofs, filling the furrows between iron-hard ridges of plowland.

But the streets of the capital were still bone dry. Solo slithered the DS around the cobbled square in front of the minuscule palace and crossed the high bridge to the biggest building in Luxembourg—the great gray mansarded rectangle housing the headquarters of the European Iron and Steel Federation. Beneath him, in the chasm that cleaves the city into two fairytale halves, lights were already gleaming in the dusk below the turreted cliffs.

He drove on down the broad main shopping avenue, passed the railway station, and took the road for Thionville and Metz.

By the time he was due to pull off the road and wait for Illya's next transmission, he was in the middle of the industrial complex between Metz and Sarrebruck. It was like a scene from some medievalist's idea of hell. Although the snow had not yet reached here, the night had come early with an unnatural overcast, and against the livid sky rows of gaunt iron chimneys belched flame. From factory to black factory, huge metal pipes fifteen feet in diameter writhed across the blasted countryside like the entrails of some galactic robot—bridging roads and railway yards, swerving around tips, linking furnaces and works and mines. And over it all, sandwiched between the fiery clouds and the dead surface of the earth, the polluted air hung sulphurous and heavy. Even with the Citroën's windows wound up, Solo could smell it in the car through the ducts of the ventilation system.

It was time for him to stop, but he did not know quite what to do. The road was narrow and full of traffic. The sidewalks, below the high corrugated iron fencing, were crowded with homegoing workers. The few parking spaces he found were too busy—for although he did not have to have total privacy, holding the baton to his mouth and operating the direction-finding equipment would be bound to excite attention in any place that was not at least comparatively quiet!

Finally he saw a patch of dusty grass bounded by a hedge white with some airborne waste. It was too public a place to carry out his task, but at least he could leave the car. He steered up over the sidewalk and stopped the DS by the hedge.

Waiting until the press of cyclists and walkers had thinned, he got out with his equipment and looked around.

On the far side of the road was a red brick building surrounded by transformers and generator housings and gantries bristling with insulators and wires. In front of it, tubs full of dispirited flowers bordered a parking lot.

Beyond the hedge, stunted trees punctuated the rusty topography of an automobile junkyard. He could see, beyond the piles of crumpled fenders, the concertinaed witnesses to death and disaster and moments of inattention, a wooden hut by the entrance gate. It should be quiet enough in there, in the dark, for his purpose—provided he could get past the man on the gate.

Or was there, perhaps, another way in, a back entrance?

Strolling casually, he found that there was. A little way along the road, a lane cut up between the yard and the high brick wall of a foundry. And a hundred yards along the lane, there were tire tracks in the mud going through a gap in the hedge. Glancing swiftly back to make sure he was unobserved, Solo slipped though.

A few minutes later, transceiver in hand, he was sitting comfortably enough on a pile of used tires, completely hidden by the stacks of wrecked ears.

The larger heaps consisted of motor bodies from which everything of value had been removed—mangled steel skeletons minus engines, wheels, instruments, springs, transmissions, seats and even the trim from the doors. But between these bigger piles there was a variety of other scrap.

There was a mound of radiator cores, another of bolt-on-wheels, a third of bench seats, mildewed and torn, with springs and stuffing leaking forlornly from their worn surfaces.

A pile of cylinder blocks from which the pistons and valves had been removed lay next to a great tangle of exhaust piping. And between the layers of unidentifiable pieces– the sheared-off fenders, bumper guards, side panels and rubbing strips—an occasional whole vehicle, or what was left of it, stood out.

There, for instance, was an American roadster that had obviously been in a head-on crash—the wheels and engine were in the passenger compartment, and the whole of the vast hood was crumpled into nothing, like a sheet of tissue. On the other side was an Italian minicar that had been squashed almost flat in some unimaginable collision. In contrast there were several trucks that looked as though they had died peacefully of old age. There was an old Unic with grass growing out of the remains of its driver's seat that must have been rusting quietly there since the year one. Beyond it was a delivery van that couldn't have had more than two square inches of its paneling that hadn't been dented or scratched—but that couldn't have been more than two years old at the outside. And nearer to Solo was a dump truck on which the back and sides were literally falling to pieces.

It was odd, though, the agent thought idly, how different parts of a vehicle deteriorated at different rates. The engine of that one, for instance, looked quite clean and well oiled, from what he could see through the half-opened hood panel. Absently, he rose to his feet and sauntered over.

Abruptly he stiffened. He stepped up to the derelict in half a dozen determined strides. The same white dust that covered the leaves on the hedge lay thickly over everything in the yard.

Except, it seemed, in the case of this truck...

He peered into the cab. The seat was threadbare, the rubber floor mat worn through, the controls shabby in the extreme. Yet there was hardly a trace of the all-pervading dust... and the cabs of the others were covered.

Quickly and silently, he walked around and lifted off the hood panel. The engine was positively gleaming. The plugs looked new, and the leads must have been replaced within the last few weeks. He unscrewed one of the caps on top of the battery. The cells were full.

Solo hurried over to the other trucks. As might have been expected, their engines were caked in dried grease, the wiring cracked, the top surface of everything strewn thickly with the white dust. The one with the dustless cab might just have been sold to the junk man, of course... but it looked to him much more as though it had been there for some time but had recently been restored to running order. It had been left looking decrepit deliberately, although in fact it could probably run quite well.

Why?

What use could anyone have for what was in effect a "Q-truck," hidden in a junkyard?

Unbidden, Tufik's parting comment leaped into Solo's mind. "It's not always the new ones that travel the best."

He dropped to his hands and knees. The street lamps, reflecting an adequate light over the rest of the yard, didn't help much at ground level. But as far as he could see, there were faint tracks leading from the truck's front wheels to the gap though which he had entered.

And suddenly, in a flash of inspiration, he saw a reason. He saw why someone could want a serviceable truck disguised and kept hidden in a scrapyard. He saw why it could be important that the vehicle, however well it ran, should appear to an outsider to be derelict. "It's not always the new ones..."

The transceiver in his hand was bleeping. Kuryakin was on the air.

Solo pulled up the antenna and thumbed the button. He sank down once more on the pile of tires and spoke softly into the microphone. He was smiling.

"Channel open," he said. "Come in, Illya... but before you say anything answer me a question: apart from the furniture van you left Prague in, has the rest of your journey been done in trucks and vans that have had their day? Old crates fit for the junk heap?... It has?... Then pin back your Russian ears and listen: I think I've found out how the network does the trick!..."

Chapter 13

A Parley Between Friends

"I AM VERY PLEASED, Napoleon," Kuryakin said. "Tell me about it... You can talk for some time because my—er– conductor has gone off to find some food. We are both hungry."

"Okay. Tell me first, though—where are you? Or don't you know?"

"This time I do. We had to walk across the border. We left the trailer truck in some Godforsaken village near Berchtesgaden, but on the Austrian—"

"The trailer truck," Solo interrupted, "was it by any chance left in a junkyard?"

"Well, yes it was, as a matter of fact! How did you know? That's all the thing was fit for, the junkyard, believe me!"

"I do believe you, Illya. You've no idea how pleased it makes me to hear it!... But you were saying..."

"About the frontier. Yes, we sneaked over without being spotted. The actual border is not very well defined in that area. We seemed to walk over half the mountains in Europe. Part of the time we were above the snow line and I was frozen! Then at last we came to another village tucked away in a fold of the hills—and I was told we were in Germany. Big deal!"

"You said you knew where you were now."

"Still only fifteen or twenty miles from Salzburg. We picked up a closed truck at this village—"

"From a junk heap again, I suppose?"

"Kind of. From a lot behind a garage full of unbelievably old cars. They were labeled for sale... Anyway, we pried out this truck and drove to a little place called Siegsdorf, just off the Salzburg-Munich Autobahn. There's a river, a railway station, a beer cellar, a Gasthof —and us. And we're stuck unseen in the back of an old heap. Or at least I am!"

"When are you leaving, Illya?"

"'At night' is all I'm told. I think we're supposed to get into Switzerland through the tunnel beneath the Boden-See—and I imagine they want to wait until the night shift is on again. It seems easier for escaped murderers."

"Especially the way this routine works. Look... Illya… Waverly briefed you on such background as we have, didn't he?"

"I think so."

"Well, it all figures, man. It all figures. Listen—Waverly was picked up in an ancient Minerva taxi that nobody has ever seen before or since, right?... He met the men with the new passport in a lane leading to a junkyard, if I remember correctly—and they were standing by an old truck."

"Yes, Napoleon. That's right, but—"

"Mathieu, the man the French were after, got away from Paris in a dust cart... and it was of a pattern that is obsolete now, the kind you'd only find in a junkyard. He changed into a 'beat-up delivery van,' to quote my friend in the Police Judiciare. And then they lost the trail near Avallon—where there are several yards full of wrecks from the dangerous section of N.6. What d'you bet that van ended up in one of those yards, eh?"

"I'm sure you are right."

"Neither the dust cart nor the delivery van have ever been found. Nor has the prewar dump truck in which the insurance embezzlers were traced as far as Limoges before they disappeared into thin Spanish air. Nor has the van from which I escaped near Maastricht the day before yesterday—although I was telephoning the police and Interpol within minutes of leaving it. Nor, I am sure, has the old deux chevaux that nearly ran me down in Paris."

"Napoleon," Illya said. "This sounds most conclusive, but—"

"Right now, I'm actually in a junkyard," Solo continued excitedly. "This program comes to you by courtesy of the European Iron and Steel Federation, Oxydized Division… and among the rust is a truck that looks finished but has been restored mechanically to fair running condition."

"Napoleon…"

"What's the odds that all these mysterious disappearances, Minerva and all, have been into junkyards? What better place can you think of for hiding old vehicles? And conversely, suppose that a whole string of yards like this, a chain of them right across Europe, were fitted up, each with a 'Q' vehicle like the one I found here—what better system could you find for running a clandestine transport service?"

"If you would just let me—"

"It's perfect! There are wrecking yards everywhere, all along the length of every traffic artery on the Continent. There have to be, with the amount of accidents there are. And as far as the network goes, it's simple—the escapee is taken a certain distance in one of the trucks or whatever. Nobody pays any mind to an old truck—and they always travel at night anyway, you say. Also, there's nobody to complain about the truck being improperly used, as it doesn't belong to anyone."

"Yes, that's it. And you see—"

"If there is any doubt, however, or if for security reasons they want to switch vehicles, then they just rum into the nearest yard on their list, leave the truck and continue the journey in another tattered wreck that's ready waiting for them. They use the yards in fact exactly like horsemen and coaches used to use the stages, the coaching inns."

"I'd like to say just a word. One word—"

"But it's perfect! It's brilliant! A near write-off is difficult to identify. In the yards, nobody is likely to notice the absence of one vehicle and the addition of another. After all, one wreck is much like another! Even at the frontiers, I guess, they could pretend to be driving the thing through as scrap. It's easy enough to forge papers verifying a deal like that."

"Napoleon!" Illya Kuryakin said loudly and firmly into the transceiver. "You are absolutely right. I know this. I can prove it!"

"Eh? What's that? How do you know?"

"That is exactly how the network operates. My chauffeur told me."

"Well, why didn't you say so, for God's sake!" Solo grumbled. "What is this fellow like, anyway? He seems the only member of the gang we've actually run up against."

"He's a short man but very tough. He looks like a walnut on legs."

"Not by any chance with a great jaw jutting out? A huge blue chin?"

"That's the one! Why—do you know him?"

"He tried to persuade me to come for a ride… and he wasn't going to charge me anything at all," Solo said grimly.

"His name is Bartoluzzi. He's a Corsican—and he used to be on the poids lourds, the long-distance heavyweight trucks. He was doing it for twenty-five years, with a break during the war; that's why he knows the European road network like the back of your foot..."

"The back of your hand, Illya."

"He's very interesting about the organization, Napoleon. But, oh dear! It's become such a bore."

"What do you mean?"

"He thinks he's tremendously tough. He probably is. But you see—the man I'm impersonating is very tough too. So Bartoluzzi feels he has to spend the whole time boasting about just how tough, how ruthless, how crafty he is. And to keep in character, I have to try to go one better, boast even more, act even more unscrupulous."

"Well?"

"You know I am not a violent man," the Russian said plaintively. "Also there is the matter of the cold food and always eating cooped up in some confined space."

"I'm afraid I don't quite follow."

"That and the continual effort to speak in a snarl or a growl or with a deep voice–it's giving me indigestion!"

Solo laughed. "It'll broaden your horizons," he said. "But I'm glad your friend is talkative. Maybe you can get him to Tell All about the other members of the organization."

"That would be impossible, Napoleon."

"I don't see why. I mean, if he has already told you—"

"It would be impossible because there isn't any organization."

"You're out of your mind! You just told me... you just said..."

"No—that's literally true. There's no organization. And our friends can hear no talk, no underworld gossip about the deal, because there is nobody to talk; incredible as it seems, Bartoluzzi is in it alone."

"You can't mean…?"

"The truth of the matter is, it's a one-man show!"

Chapter 14

The Retreat Of Illya

NAPOLEON SOLO'S characteristic low whistle of astonishment filtered clearly through the gauze of the miniature speaker. Holding the baton in the gloom of the old truck, Kuryakin raised a blond eyebrow in amusement.

"But that's unbelievable!" Solo's voice exclaimed. "Unbelievable!"

"True, nevertheless," the Russian replied soberly. "He's explained it all to me in the greatest detail, boasted about it. And although it seems incredible at first, you'll see when you think about it that it's the only sensible way to do the job, given the limitation that, necessarily, only a single job can be done at one time."

"Yes, but... it can't be true, Illya! I mean there are masses of other people involved. I know there are. Even in the few cases we know of. Take Waverly, for instance—there was the driver of the taxi, there was the ferryman, there were the three men in leather coats, to say nothing of the mysterious Willem and the missing crew member of his boat. Or take your own case; besides your driver, there are at least two—no, three!—others involved. The girl, the night watchman, and the genuine driver of the furniture van. There must have been a minimum of three men on Mathieu's dust cart to make the crew convincing. And there was the pilot of the plane to Corsica, too. So how can you say—"