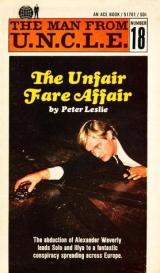

Текст книги "The Unfair Fare Affair "

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

"You got a line on the car he changed into?"

"It was a beat-up delivery van, actually. Yes, we did. They took the autoroute, and we can trace them to a place just beyond Avallon. After that, the trail goes cold—but there is a small private airfield between Saulieu and Changy, in the Morvan. Bel-Air, I think it's called. My guess is that they changed cars at Avallon and then took a plane for Corsica at Bel-Air."

"The guy's definitely in Corsica, is he?"

"Without a doubt," Rambouillet said mournfully. He sniffed and reached out his hand toward a tin of antiflu tablets on the desk. "I wouldn't mind being there myself at this minute," he added. "This perishing winter..."

Solo grinned. "No clues to pick up in the dust cart or the van?"

The superintendent produced a sodden handkerchief from the breast pocket of his jacket and blew his nose violently. "No," he said. "The funny thing is, we couldn't find a single trace of either of them. Nobody has seen them, nobody knows where they are. Which means the whole team can't have gone to Corsica—some of them were evidently left behind to tidy up."

"So it was a highly organized deal, then?"

"Of course it was highly organized. You don't slip through a number one priority cordon by chance!"

"Sure. You believe this inter-European escape deal exists, then?"

"Believe it? I know it, monsieur Solo!" Rambouillet placed two villainous-looking green pills on his tongue and gulped water noisily from a glass by the telephone. "That is not to say, of course, that every person who flees from the law, every smuggler who crosses a frontier without having his passport stamped, is a client of these people. But certain– shall we say important?—escapes have definitely been arranged by them."

"Including Mathieu's?"

"Including Mathieu's. And that of Berthelot, who escaped from Fresnes after killing a warder. And those of Vanezzi and Ponchartrain. And of course that of Paschkov, whom I we had arrested and promised to extradite to Moscow. Very embarrassing, that!"

"Do they have anything in common, all these?" Solo asked. "I mean, can you tell at once whether an escape is an organization plan or simply a one-shot job, privately organized?"

Rambouillet rose to his feet and walked over to join Solo at the window. Beyond the quai des Orfèvres, the wash from a barge rolled slowly outward to fragment the dun reflections of the trees along the Left Bank. Traffic, shiny in the rain, swooped toward the Pont Royal above the parapet. The superintendent sighed, and blew his nose again.

"I cannot tell you whether the organization jobs have anything in common or not," he said finally. "Or at least, yes–one thing I can tell you: they have this in common… that we have been able to find out nothing about any of them. Nothing at all! No abandoned vehicles, no discarded clothes, no suspicious purchases in stores. Nothing. I have men infiltrated into every big-time racket in the country, monsieur Solo; I have a list of indics—of informers—that is the envy of my colleagues in Berlin and Rome. But from none of these people can I receive even so much as a whisper concerning the makeup of this network, the names of its members, the way it works, how to get in touch with it, anything."

"But that's incredible," Solo said.

"It is incredible. I agree. In the underworld, as you well know, there is always gossip. Jealousy or envy or greed or revenge inevitably leads somebody to talk. Sometimes. But not here. Every avenue leading to this organization is blocked."

"At least you can admit that it exists and that it baffles you! And that's more than our colleagues beyond the Pyrenees are prepared to do."

"Ah, but you see, you have to take into account the Spanish character," Rambouillet said. "They are a proud people, anxious not to lose face, and it is perhaps understandable that they prefer to ignore officially a problem until they can announce it has been solved."

"All the same, I can't see why—"

"One of their own proverbs sums up their attitude in this case rather neatly," the superintendent interrupted. "in Spanish, it says, 'No creo en brujas—pero que las hay, las hay!'"

"Which, being translated, means

"Freely translated, that means roughly, 'Me, I don't believe in witches... but as far as their existence is concerned—oh, they exist all right!'"

Napoleon Solo spoke to Waverly on the ultrashort-wave transmitter hidden in a false chimney above the apartment of U.N.C.L.E.'s man in Paris.

"It seems," he said reluctantly, "that there definitely is such an organization—and there the story ends."

"I do not follow you, Mr. Solo." Waverly's voice crackled irritably from a speaker concealed in a bookcase. "Please be explicit."

"There appears to be an organization, strictly commercial and apolitical, which arranges for people to pass clandestinely from one country to another. It does not seem to effect the actual escapes—that is to say it won't spring a guy from jail. But once he is sprung, it'll get him away. It's never failed yet, and it leaves no clues."

"Ha! So I was right! Proceed, Mr. Solo."

"That's all there is. End of story. Since nobody's ever been caught and no traces are left, every single angle leading to the organization turns out to be a dead end. I've talked with the big noises in Amsterdam, Vienna, Madrid, Turin and Paris. Most of them admit the existence of the network. None of them has a single line on it. In between times, I've been to Warsaw, Prague and Munich—and I've spent a few days delving about in the underworld myself."

"And?"

"And I have to report that they seem to be right. There's not a whisper to be heard about this group all the way from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Not a single cheep from a single bird."

"Why not?" Waverly demanded. "Are they scared? Intimidation?"

"I guess not. Personally, I think it's simply because they don't know. It must be a very tight group—and if the regular boys don't know a thing about it, obviously they can't sing."

"But how do criminals wanting an escape arranged get in touch with these people? If nobody knows who they are, I mean."

"That's the whole secret, I imagine," Solo said. "They don't, you see. Because they can't. If they need the service– and if they're lucky—they get contacted." He paused and chuckled. "You know the line," he said. "Don't call us; we'll call you…"

Chapter 5

Open Hostility

SOON AFTER he had finished talking to Waverly, the first attempt on Solo's life was made.

He had left his colleague's apartment in the rue Francois Premier and had just crossed the avenue Georges V when a flock of pigeons wheeling away from the plane trees abruptly changed direction and swooped toward him. Solo was thinking of something else. From the corner of his eye he sensed the approach of something shadowy as the birds momentarily veered in his direction. With some sixth sense reflex he started back a pace and half-ducked.

The instinctive movement saved his life.

Before he had time to succumb to the feeling of foolishness that always sweeps over people in such circumstances, he was hurled to one side by the passage of a small van that had cut off from the traffic roaring up the avenue and, after executing a U-turn on two wheels, had rocketed down the road between the trees and the buildings.

Solo had been just about to step into the road. The pigeons had caused him to falter and check his stride, and the vehicle that would otherwise have cut him down merely struck him a glancing blow as it sped past. Fortunately he was off-balance and thus rode with the impact up to a point.

He was spun across the sidewalk, to slam into a wooden seat and collapse giddily to the ground.

Passersby ran up as he sprawled there, panting for breath. Willing hands helped him to his feet and assisted him to the bench. A man rushed out from a wine store on the other side of the road, carrying a stiff Cognac in a glass, and an elderly lady kept telling anybody who would listen to call the police. In no time at all, quite a crowd had gathered.

"It's a scandal, the way these deliverymen drive," some one said.

"Only boys in their teens," another voice added. "It shouldn't be allowed!"

"Perfectly. I entirely agree," a third chimed in.

"Did you see? He shot down here like a racing driver after making a U-turn in the avenue—a thing expressly forbidden in the Code of the Route."

"He must have been doing sixty kilometers an hour!

"Why, only last week a friend of my uncle in Clermont Ferrand…"

"The foreigner didn't have a chance..."

"Has anyone telephoned for an ambulance?"

"Is he hurt?"

Solo struggled to his feet, brushing aside the offers of help as politely as he could. His head was spinning. He was bruised and shaken but otherwise undamaged. "No, no," he said. "Thank you very much, but I am quite all right... I assure you... a glancing blow only. There are no bones broken... I was very lucky, really."

"Are you certain you wouldn't like a doctor?" a woman inquired.

"Perfectly sure, thank you, madame."

"Did you get the number of the assassin?"

Solo shook his head again. It would have done no good if he had. The vehicle had been one of those small gray Citroen vans with corrugated sides that can be seen by the dozen in any street in France. It had probably been stolen, and even if it hadn't the plates would undoubtedly have been false. In any case it would turn out to be totally unidentifiable—for the man who had used the word "assassin" in the normal motorist's hyperbole had unknowingly been speaking nothing less than the literal truth.

The driver of the van had intended to run Solo down and kill him.

Oddly enough, this fact caused Solo to smile cheerfully as he limped back to his hotel after making his escape from the well-wishers in the avenue Georges V.

For if somebody was interested enough to try to kill him, that meant that his investigations—superficial though they had been so far—were causing that person worry and annoyance. Even panic, perhaps. And this in turn confirmed Waverly's original hunch that there was something going on worth exposing—for you didn't try to commit murder in public unless you had something fairly important to hide.

All of which added up to the fact that Napoleon Solo was not, after all, wasting his time on a wild-goose chase. The job was going to be worthwhile. And so Solo smiled, for above all he liked action.

At his hotel—the small, unpretentious, extremely comfortable and fairly expensive Ile de France, in a side street near the Opéra—the vision at the reception desk handed him a letter that had come by special messenger.

The agent thanked her, turned aside—and then suddenly turned back again. She looked just as pretty, her hair demurely curled on her slender neck, her lips quizzically uptilted at one corner. "They work you a long day here, don't they, honey?" he said in French. "What time do you get off this evening?"

"Officially at eight, monsieur Solo," the girl said in English. "But I usually stay ten or twelve minutes longer. My husband works until eight too, and by the time he has got out the car and driven around here..." She flashed him a dazzling smile.

"Touché!" Solo murmured ruefully. He raised a hand in salute as the doors of the diminutive elevator slid shut.

In the envelope was a train ticket and a seat reservation on the evening express from Paris to The Hague. Attached to it was a slip confirming a booking for a single room with bath at the Grand Hotel Terminus. There was no letter or other form of message with these enclosures.

Solo sighed. The old man was up to his tricks again. They had agreed during their radio conversation that he should return to Holland and, without making his presence known to the police this time, try to pick up the trail of the men with whom Waverly himself had come in contact. His mission was simply—now that they knew the escape network existed—to find out how it worked and by whom it was run. Having done that, he was to try to find out if THRUSH had made any approaches to the principals or whether they were in any way concerned in the running of the scheme.

If the answer to either of those questions was in the affirmative, he was to report back to Waverly so that they could decide between them the best way of handing over their findings to the police in the country or countries involved.

If it was negative, he was to evaluate whether the escape organization was likely to interest THRUSH in the future and again report back for a decision on further action.

But in all these operations, it had been tacitly understood that Solo made his own way, as always, and arranged his own timetables.

The arrival of the special-delivery letter, complete with tickets and the peremptorily implicit command to use them, was a typical Waverly stroke. Presumably he had some particular reason for wanting Solo to be at that hotel tonight—maybe a contact he had instructed to meet him there. But on principle the agent asked the receptionist to look up the planes for him.

It turned out that by the time he had taken a cab out to Orly, waited for his flight, flown to Amsterdam, cleared immigration and customs, taken a cab from the airport at Schiphol into town, and traveled by train or car the 3 miles to the capital, he would get there no more quickly than he would by train!

In addition, now that he came to think of it, it was just as likely that Waverly would have arranged for a contact to meet him on the train itself.

It was also possible—Solo had to admit—that the planning boys at U.N.C.L.E. had looked up the planes themselves and had come to the same conclusion as he had regarding the time factor.

He called for his bill, checked out, and took a cab to the station.

Nobody approached him on the train, however. He ate an excellent, if rather solid, dinner. He read and he listened to endless business conversations in Dutch and German. In between times, he watched the gaunt, spare outlines of the northern landscape whirl past at 100 miles per hour in the yellow lozenges of light streaming through the windows of the coach.

The Grand Hotel Terminus was a large nineteenth-century block immediately opposite the station. Cheap souvenir shops, fried potato stalls, automat milk bars and garages surrounded the building, but inside the revolving doors all was bourgeois respectability and comfort.

The blast of overheated air that greeted him as he pushed through into the foyer was redolent of cigars, roast foods and aromatic coffee.

While he registered, he looked around him. Besides the reception desk and the porter's lodge, the foyer housed a bureau de change, a newsstand, and several other large display cases rented by exclusive men's and women's outfitters in the town. Off to one side was a lounge full of efficient-looking men and women in armchairs. Beyond this, a paved court with a rectangular fishpond and potted shrubs showed through a line of French doors. The foyer, the shallow stairs curving around the elevator shaft, and the broad passage leading to the dining rooms and the bar were all covered in a heavy carpet patterned in blue and red.

While a boy in uniform carried up his single light-weight valise, Solo was shown his room by an elderly woman in a starched uniform and cap. Apart from the usual bedroom furniture, the vast floor space accommodated two armchairs, a settee, a desk, several low tables, and an enormous wardrobe that looked like a model of Chartres cathedral in mahogany.

Not quite knowing what to do, he sat in the lounge drinking a coffee and a brandy, read the papers, and finally climbed the stairs to his room. Nobody had made any attempt to contact him.

As he left, a busload of tourists was arriving. The foyer was full of suitcases, ranked like an army before the porter's lodge, and the revolving doors spun to disgorge more and more transatlantic visitors of both sexes, short, grim-faced and bespectacled to a tourist, in search of shelter for the night.

Solo had resigned himself to a breakfast comprising a cup of coffee and a single croissant, and so it was with some surprise that he saw the tray left on his bedside table the following morning. On it there were coffee, hot milk, orange juice, black bread, white bread, whole wheat bread, jam, marmalade, rolls, slivers of raw bacon, a shelled boiled egg naked in a glass, cold ham, and several enormous slices of Gouda and Edam cheese.

He jumped out of bed, showered, shaved, and carried the tray to the largest of the tables. Such a meal, he felt, should be attacked by a man properly seated rather than by a sybarite lounging in bed!

When he had eaten as much as he could, he drew back the curtains and walked out onto the tiny balcony projecting from the façade of the hotel four floors above the entrance.

The place was on a corner of a T-junction whose cross– piece was formed by the station concourse. Opposite it was a line of stores, arid the wide road between them forming the stem of the letter accommodated at its center the terminus of a tramway line. Queues of workers who had arrived by train were already crowding the island refuges on each side of the lines, waiting to board cars for the city center of Scheveningen. It was cold on the balcony, but the sky over head was free of clouds, and bars of pale sunshine slashed the cream stucco of the buildings across the road.

Solo drew the cord of his dressing gown tight and surveyed the scene. Two men were pushing a gigantic barrel organ into position at the edge of the sidewalk below his window. It rested on four wheels and was pulled by shafts. The body of the machine must have been twelve or fourteen feet high, and on the brightly painted, scalloped wood of its canopy, multicolored lettering spelled out the legend DIE GROOTE HELDINGEN.

One of the men began turning a large handle projecting from the back of the organ while the other guided into a neat stack an unending succession of punched sheets, which the instrument vomited out concertina-wise as the rollicking, wheezing, jolly music cascaded into the wintry air.

Before the first tune was over, coins were showering down from the hotel windows and bouncing across from the city-bound workers by the trams. Solo ducked back into his bedroom to get a handful of small change.

His first toss was badly judged—the coin, lobbed too vigorously, landed some way from the organ and rolled into the groove of a tramline. Determined to succeed with the second, he leaned down over the balcony rail and tossed it more carefully toward the waiting musician.

As he bent forward, the rifle on the fifth floor of the building opposite cracked, and a bullet smacked into the brickwork behind his head.

Even as the agent's mind registered the explosion, a second slug drilled the French door, sending fragments of glass tinkling to the floor. The third shot was dead accurate. It whined across the balcony a foot above the rail, exactly where Solo had been leaning an instant before.

But by this time he was flat on his face on the cement floor, worming his way backward into the room.

Chapter 6

Enter An Old Friend

BEFORE VENTURING out of his room, Solo thought it prudent to stow about his person several devices perfected by the specialists in U.N.C.L.E.'s armory. These—which had been packed below the false bottom of his valise—included a fountain pen that fired a jet of liquid nerve gas; a cigarette lighter that ejected a sleep dart that would knock a man unconscious within a second; and a rather special pack of cigarettes. One of these was in fact a white-painted bolt of metal—and when the pack was squeezed a powerful spring projected it through the torn corner hard enough to render an adversary senseless at a range of ten feet.

There was also a tiny Berretta automatic, which the agent cached in a special holster clipped to his belt just behind his right hip. When he was dressed, it was completely hidden by his jacket.

At ten-thirty, he went warily downstairs and asked if there were any messages for him. There weren't.

He bought papers and sat in the lounge sipping Campari and soda. Every time the elevator cage opened or the entrance doors revolved he looked up. He felt absurdly vulnerable; whoever was after him seemed unusually well informed about his movements. It was a little alarming. And just because they had failed twice, this didn't mean they wouldn't try a third time. And it could be third time lucky–for them!

At eleven o'clock, Solo walked along the passage toward the dining room—and suddenly realized why Waverly had sent him here.

On the left of the wide corridor was the hotel's hairdressing salon. And from the archway leading to the reception counter and the chairs beyond, a rich and fruity voice boomed out in execrable Dutch.

Halting in his stride, the agent peered in. Surely it couldn't be true! The last time he had heard that voice had been in Brazil... and then he hadn't believed it!

But there was no mistake about it, the third draped figure before the minors, sitting lower than the others, turned out to be an enormous man in a wheelchair. Weighing more than 280 pounds, he sat with the great swell of his belly thrusting out the barber's sheet like a tent, the massive folds of flesh encasing his skull almost burying the unexpectedly humorous blue eyes twinkling among the fat.

It was Habib Tufik, alias Manuel O'Rourke!

Solo didn't go in right away. He waited by the entrance to the salon, watching the dexterous, almost balletic, movements of the barber as he guided a cut-throat razor unerringly among the convexities of the big man's chin.

Tufik—as he was originally named—had been born of an Irish mother and a Moroccan father. After an early encounter with gangsters that had crippled him for life, he had set up in Casablanca a specialized information service that had been without equal in the world. Police forces, embassy staff, military attaches, detectives, lawyers, newspapermen, crooks and secret agents from all over the world had come to him to buy the lowdown on anything from the private life of a foreign minister to the accommodation address used by an insignificant clerk. For Tufik sold information– just that. Any piece, or pieces, of knowledge required could be bought from him—at a price. He took no sides, and he asked no questions. The only reservation he had was that he would not sell information about one client to another.

His unrivaled sources had been built up over many years, and his encyclopedic knowledge derived in part from an exhaustive cross-referencing of gossip items culled from press outlets all over the world, in part from an adept system of bugging, and in part from plain eavesdropping and informing. It was said, though, that a fair proportion of the vast sums he received for his services was redeployed among the army of elevator operators, reporters, chambermaids, reception clerks, airline stewardesses, and cab drivers who supplied much of his raw material.

He had in fact enjoyed the reputation of being the most up-to-date gossipmonger on Earth... until Solo and his partner, Illya Kuryakin, had unwittingly involved him with THRUSH.[2] After that, he had survived a bomb attack on his headquarters and gone to South America, where—with the connivance of Waverly—he had begun to set up a similar organization. [3]

He had indeed for a short time been an ex-officio member of U.N.C.L.E.'s overseas staff, in which capacity he had materially helped Solo and Kuryakin to foil one of THRUSH's more dastardly attempts at nuclear trouble-making... and now here he was, of all places, in The Hague!

As the barber drew a towel down over the huge face to remove the last traces of soap, the man in the next chair rose and left. Solo slipped into the vacant seat.

"Yes, sir?" A young man with glossy black hair shook a pink sheet and held it out for the agent to insert his arms in the sleeves. The man looking after Tufik was preparing hot towels.

"Shave, please," Solo said, glancing sideways. The fat man's eyes, buried in the rolls of flesh like currants in pudding, were closed.

"Very good, sir... er.. are you quite...?"

The agent looked up absently. The barber had fallen back a pace and was staring at him with raised eyebrows. "What is it then?" Solo demanded.

"You did say... a shave, sir?"

"Certainly."

"But... but... it can't be more than an hour since your... since you had..."

Solo's hand flew to his smooth, recently shaved chin. "Oh... Oh, yes. Yes, that's true. Well, I guess I'd better have... you can trim my hair, eh?"

"Of course, sir. Just as you wish." The young hairdresser looked at him oddly and fished a comb and scissors from his breast pocket. On the outside of the starched linen, the word "Colin" was worked in crimson silk.

"Pays to keep the hair well trimmed," Solo babbled idiotically. "My favorite uncle always advised it."

"Just so, sir." The young man raised his eyes heavenward in silent martyrdom and began to comb and snip. There was no discernible reaction from the next chair. Tufik—a mountain of sheeted pink surmounted by a cone of white towels through which steam rose gently into the air—looked exactly like a strawberry sundae topped with whipped cream, Solo thought.

"My Uncle Waverly," he added a little more loudly.

Among the vaporous towels a tremor manifested itself. A fold of the damp cloth subsided, and an eye was revealed. The eye opened and stared at Solo. Then it closed again.

Solo closed his own eyes and settled in his chair. "Not too much off the back, please," he said.

A few minutes later he heard a bustle of activity to one side as the fat man was divested of his robes and towels, helped on with his jacket, and brushed down. There was a rustle and a chink of money changing hands.

"Thank you, Mynheer," the barber's voice said unctuously. "It is more than kind.... Thank you.... Until the day after tomorrow, then..."

And then the familiar, fruity tones: "Ah, think nothin' of it, Anton; think nothin' of it. When you have it, you might as well spread it about a bit, boy! For there's none as will give you a sight nor a smell of it when you're without it at all.... Friday it is, then. And now I'll be on my way– there's them as is waitin' to see me by the canalside on Sint Pietersstraat..."

And with a squeak of rubber tires, the self-propelled wheel chair was gone.

Solo did not open his eyes. It wasn't necessary. He knew the big man too well to need to make sure. Tufik appeared to be a loquacious, even garrulous person, a heedless and friendly man born with the gift of the gab. Nothing could have been further from the truth. He was in fact a shrewd operator who planned every move—and every single word in his conversation was there because he wanted it to be there, for a purpose. He had mentioned the name of a street in the agent's hearing. That was good enough; it was as good as an engraved invitation to a meeting.

A few minutes later, Solo was talking to the hall porter. "Sint Pietersstraat?" the man repeated, scratching one side of his moustache. "Yes, I think so, sir. It should be... let's just have a look at the street plan of the city.... Yes! Square G6 on the grid... Here we are, see? A small street running by this canal. You'll find it off the Duikersteeg… second or third turn after the lights."

It was, in fact, Solo found, only four blocks from the hotel. The canal was narrow, its surface completely covered with leaves. There appeared to be no current and no traffic. On the far side, the high walls of warehouses and industrial buildings cut off the view. The street itself was bordered by small houses in rather poor repair—much shabbier and less imposing than the tall edifices in Amsterdam—and there was a towpath a few feet below it, to which, every hundred yards or so, a cobbled ramp led down.

Solo noted with some amusement that to reach the Duikersteeg he had to pass along Onkelweg—Uncle's Way.

Once in the Sint Pietersstraat, he hurried along the granite setts looking for some sign of Tufik. The wintry sunshine was still quite bright, but there was a keen wind blowing and the shadowed side of the road was cold. Some of the two story houses had stable-type half doors at the entrance, and over several of these, the top half being open, slatternly women leaned. One flabby creature, wearing what looked like the top portion of a swimsuit, called out something to him in a dialect too broad for him to understand, and a burst of laughter echoed down the street.

It was singularly like Tufik to live in or near a quarter fitted with half doors like an Irish village, Solo thought to himself. But where was the Irish-Moroccan?

And then suddenly he saw him. The wheelchair was below him and to one side, parked on the towpath by the extreme water's edge. The fat man, bulging massively over its frail structure, appeared to be gazing along the line of stunted trees whose fallen leaves had choked the surface of the canal. Solo quickened his pace and went down the nearest ramp.

Although he had his back to the agent, Tufik somehow sensed his approach. Before he reached the foot of the ramp, Solo saw the wheelchair turn through ninety degrees, so that it was facing away from the canal, and begin to move toward the wall separating the towpath and the roadway. Then, to his astonishment, Tufik was apparently swallowed up by the brick façade. As smoothly as a rehearsed stage exit, the sequence of events unfolded—Solo's approach, the fat man's realization of it, the spin of the chair, the unhurried progress to the wall… and the final disappearance of chair and occupant!

Slowing his walk to a casual saunter, Solo reached the bank, glanced across the water and then—as a tourist might regard and reject—swung back toward the street. And at once he saw how Tufik had vanished.

Recessed deeply in the brickwork, a series of low arches ran along below the surface of the road. Behind them, he guessed, were shallow cellars. Most of the arches were boarded up or bricked in. But in one of them a rough wooden door gaped open. The wheelchair must have gone through this.