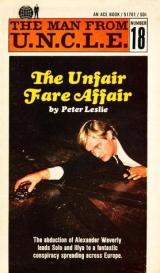

Текст книги "The Unfair Fare Affair "

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

THE UNFAIR FARE AFFAIR

Chapter 1

Mr. Waverly Is Taken For A Ride!

IT WAS NOT at all the kind of affair in which the sophisticated operatives of U.N.C.L.E. usually found themselves embroiled. Indeed, the Command would probably never have been brought into it at all except that the Policy and Operations chief of Section One unexpectedly found himself suffering the pangs of hunger one wet afternoon in Holland.

Alexander Waverly, however, did find himself thus famished that day and decided to seek a shortcut back to his hotel in Amsterdam. And that's when the trouble started. For in taking this step he inadvertently stumbled on the first small pointer that was to lead the United Network Command for Law and Enforcement into one of the most bizarre assignments ever handled by those superlative agents Napoleon Solo and Illya Kuryakin.

Waverly had been attending an Interpol conference in the Dutch capital and had chosen, even though it was winter, to stay on for a few days' vacation in Holland.

He had listened to the carillons and barrel organs of Amsterdam, and he had made the tour of the canals. He had been to Delft, to Leiden, and to Arnhem; he had visited the radio station at Hilversum and the Philips electronics empire at Nijmegen. He had admired the superlative planning of Rotterdam's postwar shopping center, and he had found him self a boy again amid the miniature docks and airfields and city streets of the model town of Madurodam, near Scheveningen. And today he had made up his mind to take a walk in the country for a change.

It had been a fine morning, and he had taken a bus all the way to Amersfoort and then another up to Harderwijk, which lay eastward from Amsterdam across a stretch of what had once been the Zuider Zee.

After a modest lunch in a dark-beamed bodega whose tables were spread with covers resembling squares of red-flowered carpet, he had decided to cross over to Oost Flevoland. The island of reclaimed land was featureless and flat in the wintry sunshine. On one side of the dike carrying the road along which he walked were inundated fields. On the other, the cold gray waters of the Ijsselmeer stretched away to the cranes and funnels and mellowed brick waterfronts of Amsterdam. And ahead, an irregular line of trees apparently growing out of the desolate sea marked the position of the Noordholland peninsula just over the horizon.

He had walked about five miles, a third of the distance to Lelystad, when the sun withdrew behind a dark bank of clouds that had blown up from the west.

Waverly hesitated. He scanned the sky, and his lean, creased face crumpled into an expression of irritation. He had intended to go on to the town in the hope of getting a ear to take him to Kampen, back on the mainland, and then Zwoll—from which he could have caught a bus back home. But it was getting confoundedly overcast and cold; it looked like rain... and there was this sudden ache in his middle that told him he needed food.

Abruptly he turned about and retraced his steps. He would go back the way he had come. It would be much quicker in the long run, he would be able to eat sooner, and if he was lucky, he would find a shortcut and avoid following the curve of the coast the way he had on the outward journey.

The island was crisscrossed by dikes. Soon he found one leading inland in the direction he wanted, and he left the road.

He had been walking along the waterlogged path for only a few minutes, when there was a low murmur of wind, stirring the grasses at his feet, and a squall of fine rain blew past him like a cloud of smoke.

Soon a persistent drizzle was falling from the pewter sky. It rolled up behind him from the west, dewing the shoulders of his light tweed topcoat, soaking his trousers behind the knee, and trickling down his neck. Amsterdam had disappeared in the mist, and the ripples flowing across the Ijsselmeer were breaking into tumbles of gray foam.

Somewhere ahead there were osiers and clumps of alder shielding a mansarded slate roof—though whether the building was on the island or across on the far side of the water he could not yet see.

Below the dike, the green of the drenched polder was almost indecently bright beneath the sullen sky. Farther away, plowed fields were awash, the tops of the ridges barely surfacing above the water in the furrows. A long way to the south, the domed tower of a church rose above the flat land, but otherwise there was no sign of life; not even a windmill, Waverly thought bitterly, to look at!

When he came at last to the strip of water dividing Oost Flevoland from the mainland, he found to his disgust that he had miscalculated: he was nowhere near the bridge, and there wasn't a causeway or a ferry to be seen.

Fuming, Waverly hunched deeper down inside the wet collar of his coat and squelched along the waterlogged grass at the water's edge.

Before long he rounded a spinney and found himself a few yards away from a boatman sitting inside a crude wooden shelter. At his feet a kind of punt rode the rain-pitted swell lapping at the sandy bank. Waverly looked over the channel. It was about three hundred yards across. Beyond a belt of trees on the far side, he could see the roofs of a village and the gleam of passing traffic on a road. From over there, surely, he would be able to get a car....

"Good day," he said in German, approaching the boat man. "I'm afraid I seem to have missed my way. Could you possibly take me across?"

"Where are you from?" the boatman grunted, rising to his feet. He was a tall man, raw-boned and craggy.

Waverly was thinking of something else. "I'm from Section One," he said absently. "Er… that is to say, I have just walked—"

"Right," interrupted the big Dutchman. "In you get, and we'll be on our way then. I've been sitting around for long enough in this perishing rain!" He reached out with one foot and drew the boat to the bank. Waverly stepped in and sat down gingerly on a wet thwart as the man took a long pole and thrust off.

For a time, the man from U.N.C.L.E. watched the two identical lines of damp countryside, one receding, the other approaching, as the boatman poled them out into midstream with long, powerful strokes.

Then, feeling a little guilty because, after all, the man didn't have to oblige him at all, he tried to make conversation.

"It's very kind of you," he began. "Still... I don't suppose you get too many people asking to be ferried across at this time of the year!"

The man grunted.

"It was most fortunate for me," Waverly pursued, "that you just happened to be there at that time. You are yourself a fisherman, I imagine?" He looked expectantly at his pilot.

"Best not to talk," the boatman said. "The less anyone knows about anyone else the better, eh?"

Waverly shrugged. The fellow seemed to be a bit of a boor. He stared for a while at the gray water sliding past the stem. Judging from the watermark on the pole, it could be no more than four or five feet deep.

When they were about two-thirds of the way across, the boatman stopped poling and allowed the punt to drift to a stand "Perhaps we'd better settle up now?" he suggested dourly. "Don't want to hang about too much by the bank, do we? It may be all right for Willem on the other side of the island, where there's nobody to see, but we have to be more careful. Anyway, I expect you'll want to be off as quick as you can. Your lot always do."

"Why... why, yes, by all means," Waverly said, reaching for his wallet. "How much do I owe you?"

He wasn't really thinking. He was cold and he was wet and he was miserable. He had had only a quarter of a chicken for lunch and that had soon vanished in the exertion of his five-mile walk. In his famished state, he could think only of getting back to his hotel—and to a large, hot meal!

The boatman had walked forward, rocking the flat-bottomed craft on the surface of the water. "One hundred guilders," he said curtly, balancing the pole across the width of the punt and holding out his hand.

Perhaps, Waverly thought, counting notes into the callused palm, he would be able to find one of those splendid Indonesian restaurants open early; a selection from the famous rijstafel would just about fit the bill... twenty and ten makes thirty, and five is thirty-five... and talking about hills... "A hundred guilders!" he screeched suddenly, his hand in midair. "But that's almost thirty dollars!"

The boatman stared at him impassively. He said nothing.

"Thirty dollars? For crossing less than a quarter of a mile of dead calm water? You must be out of your mind!"

"A hundred guilders. That's the price."

"But that's monstrous! I wouldn't dream of paying such a price! I absolutely refuse. I—"

"Look—the fare is paid," the man said strangely. "This is extra for me. For waiting. For the weather. For whatever you like. But you either give me the money or I tip you into the water... " He rocked the frail craft from side to side threateningly. "You takes your choice and you pays the money," he added with a crooked grin as he inverted the old saw.

Waverly was speechless with rage. "This is blackmail!" he stammered at last. "It is an outrage. I... I never had such a—"

"Shut up. If the cash was so important to you, you should have made sure Willem got you here earlier. You have had all day, after all. Come now—decide!"

Waverly was so angry he could hardly think straight. God knew what all that garbage meant! What the devil had this extortion to do with Willem—whoever he was? All the same, the boatman was a very big man—and he had already parted with nearly half the money. Also, even if he demanded to be taken back, he would be no better off; in fact, he would be back where he had started, with no means of crossing and thirty-five florins less in his pocket! He glanced at the oily surface of the water—it looked extremely cold!—and shuddered. Scowling, he counted out the rest of the money.

"There! That's better!" The boatman was suddenly almost affable. He stuffed the notes into his hip pocket, took up the pole, and began punting the boat rapidly toward the bank.

"Will I be able to get a car?" Waverly growled a few minutes later. "I'm in a hurry—otherwise I should never have paid your outrageous price—and I want to go—"

"Don't worry!" the giant interrupted. "Of course you'll get a car. It's all taken care of. You fuss too much."

Waverly shrugged in his wet coat and fell silent. A final thrust of the pole had sent them gliding toward a narrow creek penetrating a thicket of alders at the water's edge. Soundlessly, they slid in beneath the branches.

"You'll have to give me a hand," Waverly snapped. "There's a bank here, it's too steep and too wet and slippery to climb unaided."

"I told you not to worry," the boatman said—and indeed, as he spoke, arms reached down through the screen of leaves and hauled Waverly up and out of the boat. A few scrambling steps later, he was panting on top of the bank, staring at two men in heavy belted coats and soft hats.

"Come on if you want the car," the taller of the two murmured. "It has already attracted enough attention as it is." Taking Waverly's arm, he drew him through the bushes toward a footpath running along one side of a drowned field.

"But I didn't... " Waverly glanced over his shoulder. The punt was already back in the open water, the tall figure of the boatman blurred by the clouds of drizzle gusting in from the island.

"Best not to talk," the shorter man said.

Ten minutes and three fields later, they emerged from a belt of trees to find themselves at the edge of a country road. On the far side, a huge Minerva taxi stood in a side road half-hidden by a pile of stones.

The short man looked each way and then beckoned them across. He leaned in and spoke to a chauffeur in a peaked cap while his companion opened a door and ushered Waverly into the vast back seat. He sank down with a sigh of relief on the stained Bedford cord upholstery.

Before he could say anything, the door was slammed, the engine sprang to life, and the huge car surged forward on to the road.

Waverly twisted around and looked out the oval rear window. The two men, dwindling now in the approaching dusk, were standing in the middle of the road, each with a hand raised to the brim of his hat. He shrugged his damp shoulders and settled himself well back on the seat of the old Belgian car. He had stopped trying to figure it out… perhaps the exorbitant ferry fee included conducting him to a taxi. Yet nobody could have known he was coming; it was obviously not a regular ferry. In which case—how had there happened to be a taxi and men to take him to it?

He realized suddenly that he had given the driver no instructions. Would he go automatically to Amsterdam, because there was no civilized place in the other direction? Unable to recall the map, Waverly stared through the rain drops pockmarking the windows.

They were rattling along a narrow cobbled road that ran beside a canal. On either side, yellowing leaves drooped dispiritedly from the bare wet branches of trees.

Soon they passed a wooden bridge spanning the canal. At the corner of the timber superstructure, there was a three– finger signpost. The white-painted boards read: HARDERWIJK, ERMELE, AMSTERDAM... ELBURG, OLDEBROEK... and, on the one pointing across the canal: NUNSPEET.

Waverly exclaimed in annoyance. For the Amsterdam indicator was pointing back the way they had come!

He leaned forward to slide aside the glass partition separating him from the chauffeur. It refused to move. He tried again, harder. Still the panel would not budge.

He rapped peremptorily upon the glass. But the stolid set of the driver's head remained unchanged. The peaked cap did not turn by as much as a hair's breadth.

Waverly began to feel alarmed. Perhaps the man was deaf. Suppose he was mad, even! Maybe the whole thing was some kind of kidnap setup.... Vaguely he recalled stories of doors that would not open from the inside, of gas pumped into the rear compartment from the chauffeur's compartment, through a speaking tube.

He stared around the huge, shabby car. There was a speaking tube, hooked to the armrest on the left-hand side!

Panicking, he grabbed the tarnished chrome door handle and jerked. There was an icy blast of wind as the heavy door flew open, letting in the rumble of the Minerva's suspension and the oily hiss of tires on the wet road. Feeling rather foolish, Waverly leaned out into the spray thrown up by the wheels and hauled the door shut.

A few minutes later, the taxi slowed down by a long red brick wall and turned into a lane at the far end of which there seemed to be some kind of junkyard. The driver braked to a halt, jumped out and opened Waverly's door. "Very well, Mynheer," he said. "The other party's waiting."

He jerked a thumb at three men in long green leather coats who were leaning against a decrepit truck in the shelter of the wall. One of them plucked a cigarette from his mouth, pitched it into a puddle filling a rut in the muddy lane, and lounged forward.

"You took your time!" he said in German. "We'd almost given you up."

"Jaap was late with the boat," the chauffeur said apologetically. "According to Hendrik, he never said why—just pushed off again to the island."

"Never mind. So long as the client's here... Okay then, Herr Bird-of-Passage—let's have your passport."

Bewildered, Waverly had climbed out of the car. More puzzled still, he looked now at the outstretched hand of the man in the leather coat. "Are you talking to me?" he asked.

"Look, don't mess around," the man said crossly. "I'm hardly likely to be asking for one from Willi here, now am I?"

"Yes, for God's sake do hurry, man," another member of the reception committee called from the truck. "We're half– frozen waiting here."

"You want my passport? My passport? Are you some kind of... of police patrol?"

"Police patrol he says! That's a good one!" the man in the leather coat guffawed. "Of course we want your passport; you don't think we fit you up with a new one and still leave you the old one, do you?"

"I haven't the least idea what you're talking about," Waverly said.

There was a sudden silence. It was quite dark in the lane. A gust of wind shook a scatter of heavy raindrops from the bare branches overhead. Squelching in the mud, the other two men moved slowly up to Waverly and their companion. "What did you say?" one of them asked softly.

"I said I had no idea what the hell you were talking about," he snapped. "And what's more, I don't care! All I want to do is get back to my hotel in Amsterdam. So if you'll kindly permit my chauffeur to turn-"

"Amsterdam? Hotel? What are you talking about?" the man snarled—and then, struck by a thought, added, "What's your name?"

"If it's anything to you, my name is Waverly. And I assure you—"

"Waverly! You're not Fleischmann?' the chauffeur exclaimed blankly.

"Fleischmann? I never heard of him. I tell you—"

Waverly broke off with a gasp as he was seized from behind. Rough hands dragged his overcoat and jacket down over his arms, effectively pinioning his elbows. At the same time, the man who had first spoken reached out a hand and drew his passport from the exposed inner pocket. He flicked over the pages, scowling. "By God, he'll telling the truth!" he said hoarsely.

"Of course I'm telling the truth, you cretin!" Waverly shouted, scarlet in the face and struggling. "This is an outrage! I warn you that my name is one to be conjured with; you'll hear about this!"

"Be quiet, you!" the third man rapped out. "You mean it's definitely not Fleischmann, Karl?"

"Apparently not. Come to think of it, doesn't look like him."

"Then who is it?"

"That, my friend, we shall have to find out."

"Let me go this instant." Waverly yelled. "You can't go around roughing people up and taking their passports and abducting—"

Abruptly he choked on his words. The lane spun up and slashed him across the face as an enormous weight descended on his skull and the inside of his head exploded into a million incandescent stars.

Chapter 2

Solo Shrugs It Off

"AND I REMEMBERED nothing more," Waverly said sourly to his Chief Enforcement Officer, Napoleon Solo, three days later in New York, "until I woke up in this shop doorway at three o'clock in the morning."

"Wow!" Solo exclaimed. "That must have been some sap they slugged you with!"

Wincing slightly at the slang, his superior corrected him. "It was not the result of the—er—sap," he said stiffly. "There was the mark of a hypodermic on my forearm. Apparently I had been drugged."

"And held while they checked that you really were who you said you were—and that you weren't a sleeper fed in to blow their little setup!"

"Ours is said to be an alive and vital language, Mr. Solo," Waverly remarked with a pained expression. "Yet there are times..." He sighed and shook his gray head.

"Then they took you back to Amsterdam in the middle of the night and jettisoned you in the doorway of this jeweler's store?"

"In the Kalverstraat, yes. Apparently I was unable to give a satisfactory explanation of my presence there to two representatives of the law who chanced to pass by shortly after ward—I wasn't myself, you know—and I was—er—placed under surveillance for the remainder of the night."

"They slung you in the pokey!"

"Mr. Solo, please!... Of course, as soon as I was permitted to call my colleagues at Interpol, I was released. The Chief of Police was most apologetic. Most. But by the time we got around to making an investigation, naturally there was nothing left to see."

"You went straight back there with a team?"

"Well... almost. One of the more disagreeable aspects of the case was that, as you may recall, the whole thing started because I was hungry. You will also remember that at the time I was bludgeoned into insensibility, I had still not eaten. With the result that, despite a severe headache, I was ravenous when I recovered consciousness at 3 A.M.

"I can imagine," Solo said, repressing a smile.

"Quite. And those fools of policemen refused to allow me to go to some respectable establishment and order a meal. I had to be content"—Waverly shuddered—"with a bag of fried potatoes, a cold soused herring, and a boiled sausage from an all-night stand before they locked me up. You can see, therefore, that before I set out on the following day I was obliged to cater extensively to the—er—inner man."

"Oh, absolutely," Solo said. He coughed and moved across Waverly's office to the window.

Few employees have had the opportunity of hearing their bosses explain how they were knocked on the head. But when the boss was Waverly and when the explanation included a complaint that the police arresting him had refused to allow him to go to a nightclub on the way to jail to order a meal... Solo took refuge in another fit of coughing and attempted to master his facial expressions.

"You found nothing, I suppose," he said after a moment, staring out at the tall tower of the U.N. building. It was raining in New York, too, and there was a strong wind gusting across the East River, stammering the windows in their frames.

"Nothing," Waverly echoed behind him. "Nobody had ever seen or heard of the boatman or anybody like him. Nobody had ever seen the Minerva taxi—which is odd, because there's no old-car cult in Holland, and thus a mid-thirties monster like this would be bound to attract attention, you'd think. Not a soul could be found, naturally, who had ever seen three men in green leather coats... and that was about it. We did locate the place where the taxi turned off the road. But there were so many tracks and it was so muddy in the lane that the police were not able to identify any one set."

He dragged from the pocket of his shapeless tweed jacket a brand-new meerschaum pipe he had bought in Amsterdam, jammed it between his teeth, and sauntered over to join Solo at the window.

"All right then, Mr. Solo," he said, staring out into the rain. "What do you make of it all? Cook me up a theory to fit these facts."

The agent turned and looked at him. "Unless it's a trick question, I should say it's a straightforward case of mistaken identity," he replied. "There's this little organization all set up and waiting for somebody—the man to take him from the island to the mainland, the liaison men to direct him to the waiting taxi, the men in the truck ready to supply false papers... and from there on down."

"I agree. But why pick on me?"

"I guess they were expecting somebody from the island, somebody they didn't know too well by sight, and you turned up around the right time. I imagine you inadvertently gave the right password or innocently supplied the correct answer to a coded question. Something like that."

"That's exactly what I thought," Waverly agreed. "I said, in German, 'Good day. I seem to have missed my way. Could you take me across.'"

"Ah. That was probably the opening gambit."

"I think it must have been. For he showed no surprise at all. Nor did he answer the question. He simply asked me where I was from, and when I replied absently—I was thinking of something else, you know—that I was from Section One, he got straight up and pulled in the boat."

"That's it! That's it! The approach in German—and then, by an extraordinary coincidence, the right code word when you say Section One!"

"I expect you're right. Because, come to think of it, I spoke in German; yet he replied in Dutch. And that's the way it went on—German from my side, Dutch from his. I can understand Dutch, you see, but I don't actually speak it. One surmises that this was another part of the arrangement, the twin language thing."

Waverly paused, sucked noisily on the empty meerschaum, and reached into his pocket for a tobacco pouch. "Well, that's all right, as far as it goes," he continued, "but how do you see the thing in its broader aspects?"

"As a continuing organization, I think," Solo said after he had considered for a moment. "Rather than as a one-shot job, I mean."

"Why do you say that?"

"Several reasons. The boatman said he expected you wanted to be off as quickly as possible and added, 'Your lot always do.' Secondly, nobody knew the taxi, although it was easily identifiable. If it had been a one-shot job, they could have used a local car and bluffed it out—but a mystery auto spells organization to me! Third, all that insistence on 'it's best not to talk.' A hastily improvised organization would risk nothing by talk; but one that had subsequent tasks of the same nature to carry out… well, obviously the less known—and said—the better!"

Waverly nodded. "Yes, that's all good reasoning," he said.

"As to what such an organization is... well, my guess would be that it exists to smuggle undesirables—or contraband goods, even—into Holland. Judging from what you said, the mysterious Willem lands the clients on the north coast of the island, and they then walk across and meet your boatman on the south. And he in turn hands them on to the taxi and the men in the truck."

"Going where?" Waverly asked softly. "If they're already in, why would they need to be squired further?"

"Squired further…? Oh—I see what you mean." Solo was silent for a moment, and then he said slowly, "Long, green leather coats, did you say? Of a particular dark bottle green?"

Waverly nodded, stuffing tobacco into the vast bowl of the pipe.

"Then that suggests northern Germany, Westphalia, to me. There is a certain type of German, especially among the older ones, who automatically wears a coat like that in winter. Particularly in places like Hamburg, Bremen, Oldenburg, and so on."

"Precisely."

"In which case, it argues that Holland was only an interim stage on the route. That also fits in, of course, with the fact that the 'client' was to be issued with a fake passport after he had entered the country. If the three men were Germans, the passport would be required for crossing the German border."

Waverly tamped the tobacco down with his thumb and put the meerschaum back between his teeth. "That's the way I see it," he affirmed.

"This also takes care of the taxi. Suppose it is in fact a German vehicle which only appears in Holland when there is a job on, when they fit it out with false Dutch plates. Well, there's no wonder the locals haven't seen it! And then, when the passenger has been duly equipped with spurious German documents, they merely change back to the genuine plates and drive across the border!"

"Exactly. There are two dozen small frontier posts between Emmen and Enschede, any one of which they could have been heading for when they realized I was the wrong man. They could use a different one every time, to minimize the risk of someone noticing something."

It was Solo's turn to nod. "Yes, it all figures," he said. "Even the client's name—Fleischmann, did you say it was?—is German. I'd guess it's a big-time outfit too; your boat man said something to the effect that the fare was paid, didn't he? That implies large-scale operations to me—you pay the fare before you start, and everything's taken care of, just like on a travel-agency tour! No doubt that was why your ferryman turned on the screws and asked for the extra: Willem's man was for some reason late and, being a fugitive as it were, could scarcely refuse the demand!"

"Where do you think Willem's man came from?" Waverly asked.

"Looking at the map, I imagine the boys bring illegal immigrants from America—or anywhere overseas, for that matter—into the Federal German Republic. Probably the clients are stowed away or in some other manner smuggled aboard boats docking at Amsterdam. And then, when they get there, instead of walking down the gangway, they drop over the blind side, as it were, make for the other bank of the Noordzeekanaal, cross the neck of land dividing the canal from the Ijsselmeer, and pick up Willem there."

"But why should they bother to cross an inland sea, traverse an island, and come back to the mainland again when they could just as well have gone around the edge of the sea in the first place?"

"Simply because of the relative danger, I guess. A man without papers, a man on the run, is a natural target in a seaport, on the streets of a capital city, on the main roads—most of which are patrolled by police. But if you take him to a desolate stretch of country that's underpopulated and put him in touch with the people who can give him papers there, well, you're halving the chances of detection right away, aren't you?"

"I thought strangers were supposed to stand out even more in country areas," Waverly objected.

"If they're going to stay, to live there, sure. But not passing through. With a bit of luck, nobody'll see them at all."

"You may be right." Waverly went back to his desk and skimped into his chair. He tossed the unlit pipe onto a pile of folders. "In any case, we shall soon know. Are you done with that Hawaiian forgery thing yet?"

"Not quite. We have to make a digest of the depositions and—"

"Hand it over to Rodrigues," Waverly interrupted.

"To Rodrigues? I'm afraid I don't quite—" Solo began.

"He's capable of handling it, isn't he?" the head of Section One demanded irritably. "All the stuff's in, isn't it?"

"Well, yes. Slade and Miss Dancer have to file a report from Manila, but otherwise everything's there. The report'll be in tonight in any case."

"Excellent. Hand it over, then."

"Very well, Mr. Waverly. Did... did you have some thing else, something urgent, for me?" Solo inquired, his dark brows raised in puzzlement.

"Yes, I did," his chief said crisply. "I want you to fly to Amsterdam tonight and find out all about Willem…"

Chapter 3

A Question of Etiquette!

NAPOLEON SOLO was incredulous. "You can't be serious!" he said in dismay. "You don't mean... officially? Not as an assignment... for the Command?"

"Of course I'm serious," Waverly said testily. "And for whom else would it be an assignment, if not for the Command?"

Solo gulped. Perhaps the old man was going out of his mind. Maybe the blow on his head had been harder than anybody realized. He would have to play it very cool if he was to prevent the head of Section One from making a fool of himself.