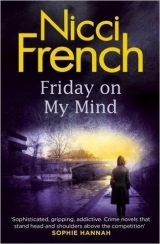

Текст книги "Friday on My Mind"

Автор книги: Nicci French

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Frieda smiled at her. ‘You’re the only person who’s actually dared ask.’

Suddenly Sasha’s face was very pale. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I feel –’

And she stopped.

‘What do you feel?’

There was a loud series of knocks on the front door, followed almost immediately by another.

‘That’s Frank,’ said Sasha, standing up. ‘He always knocks like that – impatiently, as if I’m keeping him waiting.’ But she spoke tolerantly.

She went to let him in and Frieda put her head under the tablecloth.

‘Frank’s here,’ she said.

Ethan looked up. His face was very close to hers and she could see herself reflected in his deep brown eyes. ‘Come in my cave,’ he said. ‘It’s safe.’

At twenty-five past nine the following morning, Friday, 27 June, one week after Sandy had been found in the Thames with his throat cut, Tanya Hopkins arrived at the Waterhole café and secured a free table looking out over the canal. It was a beautiful June day, clean and fresh, with the last softness of morning in the air. People walked, ran, biked past the window. Ducks bobbed among the drifts of litter in the glinting brown water.

Tanya Hopkins ordered herself a cappuccino and a pastry. She checked her phone for messages but there was nothing important. She drank the coffee and tore off pieces of pastry. She opened her notebook and put it in front of her on the table. She looked at her phone once more. It was twenty minutes to ten. She pressed Frieda’s number and listened to the ringtone. The call went to voicemail and she left a curt message.

She wrote the date on the top of the page of her notebook and underlined it, finished her cappuccino and thought about ordering another. But, no, she would wait until Frieda arrived. She shaded the letters, then cross-hatched them, and then she crossed them out in impatient black lines.

When she looked at her phone again, it was past a quarter to ten. In fifteen minutes, they were meant to be at the police station. She called Frieda’s number once again but this time left no message. Her irritation had turned to a heavy anger that sat like a stone in her stomach.

At five to ten, she paid and went outside, looking up and down the towpath for her client. She walked up the steps and gazed around. She phoned one last time, without expectation. She waited until three minutes past ten and then she went into to the station and announced herself. She was shown into DCI Hussein’s room.

‘Something must have happened to hold Frieda up,’ she said, in a pleasant voice. ‘We’re going to have to rearrange her appointment.’

Hussein looked at her across her desk. She was very still and her face was grim. ‘So,’ she said at last. ‘You’re not serious?’

10

Commissioner Crawford pointed a quivering finger at the chair and Karlsson sat down.

‘Do you know why you’re here?’

‘I can guess.’

‘Oh, spare me your playacting. Of course you know. Your Frieda Klein has absconded. Disappeared. Buggered off. Gone.’

Karlsson didn’t move. Not a muscle of his face changed. He stared across the large desk into the commissioner’s face, which was so red it was practically steaming. He could see the tidemarks of anger in his neck, above his shirt collar. ‘Did you know? I said, did you know?’

‘I knew that she had gone.’

‘No.’ He banged his fist on his desk so his empty cup shifted and the pens rolled. ‘I mean, did you know she was planning to go?’

‘No. I didn’t.’

‘I know that she has talked to you.’

‘As a friend.’

‘A friend.’ The sneer in Crawford’s voice made Karlsson stiffen; his mouth tightened. ‘We all know about you and Dr Klein.’

‘I talked to her as a friend.’

‘With her solicitor. You were there with her fucking solicitor. Jesus. You are in such shit here, Mal. Up to your neck.’

‘Frieda Klein is a colleague, as well as a friend. We’re supposed to look after our own.’

‘Ex-colleague.’

‘I know you’ve had your differences –’

‘Stop it, Mal. This friend, this colleague, has murdered a man and now she’s run off before we can charge her.’

‘I’m sure there’s an explanation.’ The dull ache behind Karlsson’s eyes had spread and now occupied his entire skull. He thought of Frieda the previous day, how she had hugged him, although they had never touched each other except for a hand on the shoulder, and how she had thanked him. He realized now that she had been saying goodbye, and he heard his words to Crawford through the thud of pain. ‘I trust her,’ he said.

‘Get out of here. If I ever find out that you’ve helped her, in any way, I’ll have your head.’

On his way out he met a grey-haired man, with tortoiseshell glasses, holding a file. ‘It’s Malcolm Karlsson, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Can I help you?’

The man looked thoughtful, as if he were genuinely trying to think of a way in which Karlsson might be able to help him.

‘No, no. Not at the moment.’

‘I’m sorry, who are you?’

‘Oh, don’t mind me. Just visiting.’

Hussein looked across the table at Reuben. Reuben wasn’t looking back at her. They were sitting in the conference room at the Warehouse. One whole wall was glass and it had a view that took newcomers by surprise, looking southward right across the city. On a clear day – and today was a very clear day – you could see the Surrey hills, twenty miles away. After a full minute, Reuben turned to face the detective. ‘I’ve got a patient in a few minutes,’ he said. ‘So if you’ve got any questions to ask, you’d better ask them.’

‘Do you know about the offence of perverting the course of justice?’

‘I know it’s something you’re not meant to do.’

‘It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.’

‘So I’m convinced that it’s serious.’

‘Did you know that a warrant has now been issued for Frieda Klein’s arrest?’

‘No.’

Hussein paused. She looked at Reuben’s face carefully. She wanted to see his reaction to what she was about to say. ‘Do you know that she has absconded?’

‘Absconded? What do you mean?’

‘She was due to report to the police station this morning, along with her lawyer. She didn’t appear.’

‘There’s probably been a mistake. Or an accident.’

‘She went to her bank this morning and withdrew just over seven thousand pounds in cash.’

Reuben didn’t reply. He rubbed his face with his hands, as if he was waking himself up.

‘You seem to be taking this very calmly,’ said Hussein.

‘I was thinking, that’s all.’

‘I’ll tell you what you need to think about. If you’ve helped Dr Klein in any way, if you discussed this with her, then you have perverted the course of justice and you have committed a criminal offence. If you’ve done anything, if you suspect anything, then you need to tell me now.’

Reuben touched the surface of the table very softly with his fingertips.

‘Do you really think she killed Sandy?’ he asked.

‘It doesn’t matter what I think. We built a compelling case and the CPS elected to prosecute.’ She leaned forward across the table. ‘This won’t work, you know. This isn’t the nineteenth century. It’s not even the 1990s. Someone like Frieda Klein can’t just disappear. What she has done is not just against the law, it’s insane. When she’s caught – and she will be – it’s going to be very bad for her and it’s also going to be bad for anyone connected with her. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘Good. Do you know where she is?’

‘No.’

‘Or might be?’

‘No.’

‘Did you know she was planning to abscond?’

‘No.’

‘Who else would Dr Klein turn to?’

‘I don’t know. She’s a very independent woman.’

‘When I met her, there was a man with her, a foreigner.’

‘You mean Josef?’

‘Yes, that was his name. Who is he?’

‘A friend of Frieda’s. A builder. He’s from Ukraine.’

‘Why would someone like that be a friend of Frieda Klein?’

‘Is that an insult to Ukrainians or to builders?’

‘How can I reach him?’

Reuben thought for a moment, then took out his phone, checked it and wrote the number on a piece of paper. He pushed the piece of paper across the table.

‘Who else might help her?’

‘Am I meant to name names, so that you can go around and threaten them?’

‘You’re meant to obey the law. Does she have any close relatives?’

Reuben shook his head. ‘One brother lives abroad, another out of London, near Cambridge. She wouldn’t turn to him and he wouldn’t help her if she did.’ Reuben checked his phone again. He reached back for the piece of paper and wrote a name and number. ‘She’s got a sister-in-law she sees quite a bit of. Olivia Klein. You can waste some time talking to her.’

Hussein took the piece of paper and stood up. ‘You were her therapist,’ she said. ‘I thought people told their therapists everything.’

Reuben gave a short laugh. ‘I was her therapist years ago and even then she only told me what she wanted to tell me.’

‘I know you don’t care what I think,’ said Hussein. ‘But a man has been murdered and your Frieda Klein has gone off on some self-indulgent meltdown. She’s wrecking a murder inquiry, breaking the law, and for what?’

Reuben stood up. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘I don’t care what you think.’

Olivia Klein also lived in Islington, further east but still less than a mile from Sandy’s flat. When she opened the door and Hussein identified herself, her eyes filled with tears. When Hussein mentioned Sandy’s name she started to sob and Hussein had to lead her into the living room, propping her up and then settling her down on the sofa. She went through to the kitchen and found a box of tissues. Olivia pulled them out in handfuls, wiping her face and blowing her nose.

‘I can’t tell you what Frieda’s done for me over the years. She’s saved me. Completely saved me. When David left, I was just completely … I mean totally …’

Her words turned back into sobs. ‘And then my daughter, Chloë, went through a terrible time, she was a complete bloody tearaway, and Frieda helped her with her schoolwork and talked to her. She even put her up for a while, which deserves some kind of a damehood.’

‘I suppose she needed a father.’

‘She needed a fucking mother as well. I wasn’t any good to her. With Sandy, I really thought she’d finally found someone and then it went wrong and then this. It’s so …’

Her face disappeared into her tissues once more.

‘Mrs Klein …’

‘I don’t know anything. I didn’t really know Sandy well and I haven’t seen him for a year. Two years. A long time anyway.’

‘It’s not that.’

‘Then what is it?’

Hussein was almost reluctant to begin because she knew what was going to happen. But it didn’t. When she described Frieda’s disappearance, Olivia just seemed so shocked that Hussein didn’t know if she was taking it in. She looked like a child, with a blotchy pale face, who had cried and cried so much that there were no tears left.

‘Why?’ said Olivia, in a small voice that was hardly more than a whisper. ‘Why would she do that?’

‘I was hoping you could tell me.’

‘How could I know? I’ve never known why Frieda does things, even after she’s done them.’

‘She’s done this’ – Hussein said each word slowly and clearly so that there was no mistake – ‘because she knew she was about to be charged with a very serious crime.’

‘But you can’t think that she did it. It’s not possible.’

‘We need to be very clear,’ said Hussein. ‘If you know anything about this, if you’ve helped Frieda in any way, then you need to tell me. That’s very important.’

‘What, me?’ said Olivia, suddenly speaking loudly. ‘I don’t even know how to work the DVD player now that Chloë’s at college. Every time I want to watch something, I have to phone Chloë up and she talks me through it and I still don’t remember. You think Frieda would turn to me to arrange an escape? I’m a drowning woman. When you look at me, you’re looking at a woman who’s literally drowning. Sometimes Frieda has rescued me and pulled me to the shore and then I’ve fallen in again. But I can tell you that, if Frieda had turned to me, then I would have done anything for her that I could.’

‘It would actually have been a crime.’

‘I don’t care. But she wouldn’t turn to me because she’s got too much bloody sense.’

The house in Belsize Park looked like it was being demolished from the inside. There were four skips lined up along the road. Old planks and plasterboard and cables were being carried out of the front door. Meanwhile scaffolding was being unloaded from a van and assembled around the façade. Hussein had to be issued with a hard hat, and Josef summoned from somewhere deep inside. Hussein had become used to the strange reactions of people when they had to deal with the police, but when Josef appeared in the doorway and noticed her he just gave a slow smile of recognition, as if he had been expecting her. She followed him into the house and he led her right through and into the large, long back garden.

‘It seems like a big job,’ she said.

He looked up at the rear façade of the house as if he were seeing it for the first time. ‘Is big.’

‘Looks like they’re taking it apart.’

‘Gutting. Yes.’

‘Expensive.’

Josef shrugged. ‘You spend fifteen, twenty million on house, then two or three more is little.’

‘Not for me.’

‘Me also.’

‘We’re looking for Frieda. Do you know where she is?’

‘No.’

She waited for him to elaborate, to protest, but he simply stopped as if he had said all that needed to be said.

‘When I met you with Dr Klein, I felt like you were there as some kind of back-up.’

‘Friend. Only friend.’

‘I read the police file on Dr Klein. Your name appears in it.’

Josef seemed to smile at the memory. ‘Yes. Funny thing.’

‘You were badly hurt.’

‘No, no. It was small thing.’ He made a gesture on his arm and a puffing sound.

‘You know that Dr Klein is now a fugitive?’

‘Fugitive?’

‘On the run. We want to arrest her.’

‘Arrest?’ He looked startled. ‘Is bad.’

‘It’s bad. It’s very serious.’

‘I must work now.’

‘You’re Ukrainian?’

‘Yes.’

‘If you know anything at all about Frieda Klein’s whereabouts, or if you’ve helped her in any way, you’ve committed a crime. If so, you will be convicted and you will be deported. Understand? Sent back to Ukraine.’

‘This is …’ He searched for the word. ‘Threat?’

‘It’s a fact.’

‘I’m sorry. I must work.’

Hussein took a card and handed it to Josef. He looked at it with apparent interest.

‘If you hear anything, anything at all,’ she said.

When Hussein was gone, Josef stood in the garden for several minutes. When he went back inside, he found Gavin, the site manager. Then he walked out of the front door, along the avenue and turned right on Haverstock Hill. He walked down the hill until he reached the hardware store. The large, shaven-headed man behind the counter nodded at him. Since the job had started, he’d been in there every day. The delivery was ready. Josef took out his phone and checked the time.

‘Back in half-hour,’ he said.

He came out of the shop and crossed the road into Chalk Farm station. He took a train south, just one stop to Camden Town. He exited the train just as the doors were closing. He looked around. There was almost nobody on the platform, except for a party of teenagers, probably heading for the market. He came out of the station and walked north up Kentish Town Road. He reached the steps off to the left and walked down to the canal. He could see the market ahead of him but he turned left away from it, under the bridge. As he walked along, he saw the occasional runner. A cyclist rang a bell behind him and he stepped aside. Ahead, he saw a canal boat chugging towards him, an old, grey-bearded man steering it from the stern. Josef stood and waited for the boat to pass him. The brightly coloured curlicued decorations made him smile. The man waved at him and he waved back. Ahead of him, he saw a familiar silhouette, standing under a bridge.

As he approached, Frieda turned round. Josef took a piece of paper from his pocket and handed it to her. She unfolded it. ‘Is he a friend?’

Josef nodded.

Frieda put the paper into her pocket. ‘Thank you,’ she said.

‘I come with you to see him.’

‘No. You won’t know where I am. You won’t know how to get hold of me.’

‘But, Frieda –’

‘You must have nothing to hide and nothing to lie about.’ She looked into his woebegone face and relented. ‘If I need you, I promise I will find you. But you must not try to find me. Do you hear?’

‘I hear. Not like, but hear.’

‘And you give me your word.’

He placed his hand over his heart and made his small bow. ‘I give my word,’ he said.

‘Have they been to see you?’

‘The woman. Yes.’

‘I’m sorry. You know, Josef, I’m not good at saying these things …’

Josef held up his hands to stop her. ‘One day we laugh about this.’

Frieda just shook her head and turned away.

11

Frieda walked along the canal and bought a pay-as-you-go phone from a little shop on Caledonian Road. She made the call, then took the Overground through the East End, crossing and re-crossing the canal, looking into back gardens, breakers’ yards, warehouses, allotments. Then the train plunged underground and after a few minutes re-emerged into the light in a different country: South London. Frieda got out at Peckham Rye and needed the map to steer her through residential streets, past a school and under-arch repair shops until she reached the housing estate she was looking for. Each large building had a name: Bunyan, Blake, and then – the one she was looking for – Morris.

A man was standing on the pavement talking on his phone. He looked as if he should have been on a touchline somewhere. He was dressed in trainers, tracksuit bottoms, a yellow football shirt with the name of a utility company across the chest and a black windcheater. He was tall, with long hair tied up in a ponytail, revealing earrings in both ears. One eyebrow was also pierced. He might have had a moustache and a goatee or he might just not have shaved for a few days. He noticed Frieda and held up his free hand in a gesture that greeted her, apologized, told her to wait. He was making complicated arrangements about a delivery. When he had finished he stowed away his phone.

‘By the time you tell them, it’s quicker to do it all yourself.’

The accent was a mixture of South London and Eastern Europe. He held out his hand and Frieda shook it.

‘This way,’ he said, and led her in through the gateway to the courtyard separating Blake from Morris.

‘Friend of Josef?’ the man said. Frieda nodded. ‘Lev.’

‘Frieda. Are you from Ukraine as well?’

‘Ukraine?’ Lev’s face broke into a smile. ‘I am from Russia. But we are like brother and brother.’

‘Yes. I’ve been reading about it in the papers.’

Lev glanced at Frieda with a frown, as if he suspected he was being made fun of, and Frieda suddenly felt that making any kind of fun of him might be a bad idea. Lev led her up a stairwell, one flight, then another, and up to the third level. He walked along the terrace. Flat after flat was bricked up with large, blue-grey breeze blocks.

‘They really don’t want people to get in,’ said Frieda.

Lev stopped and put his hands on the rail, looking out across the space towards Blake House, like a concerned owner. ‘They are pushing the people out,’ he said, ‘then the bricks.’

‘What’s happening to the place?’

‘The far house is empty. Next year they knock down and build. In two years, three years, this house too.’

He continued along the terrace and stopped in front of a door that had been whitewashed but with only a single coat so that the dark paint underneath showed through. Lev produced a key ring with two keys and a small plastic figurine of a naked lady dangling from it. He detached one of the keys and looked at it. ‘I give you the key,’ he said. ‘And you give me …’ He stopped to think for a moment. ‘Three hundred.’

Frieda took a small wad of twenties from her pocket and counted out fifteen. She handed them to Lev, who put them in his pocket without checking them.

‘For the …’ He waved a hand, searching for the word.

‘The expenses?’ supplied Frieda.

‘Some things to pay, yes.’

He unlocked the door. ‘Welcome,’ he said and stood aside to let her in.

Frieda stepped into the little hallway. There was a smell of damp and piss and something else, a rotting sweet smell. It looked as if the flat had been abandoned quickly. Whatever had been hanging on the wall seemed to have been pulled away, leaving cracked and pitted plaster. She turned a wall switch on and off. Good. There was light at least. She put down her holdall and walked around from one room to another. There was a sofa and a table in a living room, a single bed in a back room and nothing at all in the bathroom or kitchen. No table or chair, no pot or pan.

‘Do you own this?’ asked Frieda.

Lev grimaced. ‘Look after,’ he said.

‘And if someone comes and asks me what I’m doing here?’

‘Nobody come probably.’

‘If someone asks, do I mention your name?’

‘No names.’ Lev bent over a portable electric heater in the corner of the living room. He looked up. ‘When you go out, do not have this switch on,’ he said. ‘Is maybe problem. And maybe not when asleep as well.’

‘OK.’

‘You here just three weeks, four weeks?’

‘I guess. Who else lives here?’

‘Only you.’

‘I mean in the rest of the building.’

‘All kinds. Syria now. Romania. Always the Somalis. They come and they go. Except one very old woman, very old. English from long ago.’

‘Is there anything I need to know?’

Lev looked thoughtful.

‘Lock the door always from inside. They sometimes play the music very loud. The ear muffs is good, not the complaining.’

He held out his hand and shook Frieda’s.

‘When I’m done, what do I do with the key?’

He made a contemptuous gesture. ‘Thrown in the bin.’

‘And if there’s a problem, how do I reach you?’

He zipped up his jacket. ‘If there is a problem, the best is to go away to another place.’

‘Shouldn’t I have your number?’

‘For what?’

Frieda really couldn’t think of any reason why. ‘What about the next rent payment?’

‘There is not rent.’

‘Well, thank you, for all of this.’

He shrugged. ‘No, no, this was a thank-you to my friend Josef.’

Frieda didn’t want to think of what Josef might have done for Lev to have earned a favour like this. She hoped it was only some cheap building work.

‘So,’ he continued, ‘goodbye to you.’ He walked to the front door. ‘And now I think of it, maybe not to use the heater any time. Is not so good. And this is summer, so no need.’ And he left and Frieda was alone.

She paced the flat. She stopped in the living room and looked at a corner where the wallpaper was coming away. The whole place felt abandoned, desolate, forgotten. It was perfect.

First things first. She took a notepad and pen from her shoulder bag and made a list. Then she left the flat, locking the door after her, and went down the three flights of stairs, through the courtyard and back onto the street. She retraced her footsteps and soon was on the high street. The sky was a flat blue, making everything look slightly garish.

She went into a pound shop, which was crammed with all manner of apparently random objects. There was an entire section devoted to Tupperware, another to water pistols. Paper plates, bath toys, streamers, several fishing rods, mop heads, bath foam, photo frames and patterned cups; plastic flowers, toilet brushes and sink plungers; kitchenware of all kinds. Frieda selected a pack of paper plates, another of plastic forks and knives, washing-up liquid, lavatory paper, a white mug and a small tumbler, a miniature kettle in lurid pink.

She didn’t intend to spend much time in her new home and there was no fridge or cooker, but in the small supermarket a few hundred yards up the road she bought ground coffee, tea bags, a small carton of milk, a box of matches and a bag of tea-lights.

Laden now, she carried everything back to the flat and laid it out on the table. She took a bottle of whisky from the holdall and put it out as well. She had brought very little with her – just a few basic clothes, a book of academic essays about psychotherapeutic practice and an anthology of poetry, toiletries, a drawing pad and some soft-leaded pencils.

She filled the kettle with water that spat unevenly from the tap and plugged it into one of the sockets. Once she had made herself a mug of tea, she sat on the sofa, avoiding the suspicious stain at one end, and looked around her. The sun shone through the dirty window, and lay in blades across the bare floor. So this was freedom, she thought; she had cut all her ties and cast herself off.

Fifteen minutes later, back on the high street, she went into what was labelled a ‘camping’ shop: row upon row of extraordinarily cheap tents, wellington boots, 99-pence T-shirts, footballs, children’s fishing nets, zip-up fleeces and waterproof jackets. She found what she was looking for in the dimly lit back of the shop – a sleeping bag for ten pounds.

She had seen the Primark when she came out of the Underground station. She had never been into one before, although Chloë used to buy half her wardrobe there, triumphantly flourishing her haul of sandals and leggings and stretchy dresses that barely covered her backside. She entered the shop now, blinking in the fluorescent dazzle that made everything seem like an over-lit stage set, and was momentarily startled by the overwhelming abundance of things – shelves and racks and bins of clothes. A mirror blocked her way and she stopped to look at herself. A woman in austere clothes, pale face bare of make-up, hair pulled severely back: she wouldn’t do at all.

Half an hour later she left with a red skirt, a flowery dress, patterned leggings, a natty striped blazer, flip-flops with a little flower between the toes, three T-shirts in bright colours, two of which had logos on them that she didn’t even bother to read, and a shoulder bag with studs and tassels. She didn’t like any of the clothes and she particularly hated the bag, but perhaps that was the point: they were clothes that represented a self she was not, a role that she must step into.

There was still one more thing she had to do.

‘How do you want it?’

‘Short.’

‘How short? A bob, perhaps? With a choppy fringe?’

‘No. Just short.’ She glanced around her and pointed a finger at a picture. ‘Like that, perhaps.’

‘The urchin look?’

‘Whatever.’

The girl standing at her shoulder examined her critically in the big mirror. Frieda hated sitting in hairdressers, in the bright lights, seeing the endless duplications of her face. She lay back, her neck on the dented rim of the sink, and closed her eyes. Tepid water sluiced over her hair and trickled down her neck. The girl’s fingers were on her scalp, too intimate. Frieda could smell the tobacco smoke on her, and the sweet perfume overlying that. When she sat up again, she kept her eyes closed. She felt the blades of the scissors snickering their way through her hair and cold against her neck, and imagined the locks lying in damp clumps on the floor. She had not had short hair since she was a young girl, and rarely had it professionally cut – Sasha or Chloë or Olivia just trimmed it every so often. She thought of them now, each in their separate lives. Everything seemed very far away: the world on the other side of the river, the streets she walked at night, her little house in the mews, her red armchair in the consulting room, her old and known self.

She opened her eyes and a woman stared back at her. Short dark hair whose tiny tendrils framed a face that seemed thinner and perhaps younger; large dark eyes. Strained, alert, unfamiliar. Herself and not herself; Frieda who was no longer Frieda. As she left the salon and stepped out onto the unknown street, she took the thickly framed spectacles she had bought from her bag and put them on. They were plain glass, yet the world looked quite different to her.

She walked over the road to a mini-supermarket. In the stationery section she found a small notebook with a picture of a horse on the cover and a small box of pens. She bought them and walked further along the road, past a betting shop and a showroom with second-hand office furniture. On the corner was a shop with a large, bright orange sign: ‘Shabba Travel Ltd. Cheap Tickets Worldwide. Money Transfer. Internet Café’. Taped to the window was a printout of the current conversion rate for the taka. She stepped inside. Frieda hadn’t realized that travel agents still existed, but it didn’t look like any travel agent she remembered. There were no posters on the walls, no brochures. And it didn’t look like a café either. There was an array of tables, each with its own computer terminal. On the left side of the room there was a laminated counter behind which was a wall of box files and a man talking on the phone. He was sweating, even though the day was cool, and his blue T-shirt was tight on him, as if it were two sizes too small. When he noticed Frieda, he looked at her suspiciously.

‘Can I use one of these?’ she said.

‘It’s fifty p for fifteen minutes,’ he said. ‘One twenty for an hour.’

She put two coins onto the counter. ‘Which one do I use?’

He just waved vaguely at the room and continued talking. Only one table was occupied. Two young men were sitting at one of the terminals, one of them tapping at a keyboard, the other leaning across him, offering him loud advice. She sat at a terminal at the back, and turned the screen so that it faced away from everyone except her. She went straight to Google and typed in her own name. She looked down the list that appeared and felt a sudden tremor. The first item she saw was ‘Frieda Klein obituary’. It didn’t seem like a good omen. She clicked on a link that really did refer to her and saw the familiar photograph of her that the newspapers had used before:

COP DOC LINKED TO MURDER

INVESTIGATION GOES ON THE RUN

POLICE APPEAL FOR WITNESSES AS

FRIEDA KLEIN GOES ON RUN

Frieda had hoped that a psychotherapist failing to appear for a police interview might be a fairly minor news story, but she was wrong. The story appeared on site after site, always with the same photograph. One link was to a local TV news report. She clicked through and saw a blonde female newscaster mentioning her name. As she felt around the edge of the terminal to lower the volume, she suddenly caught her breath. The newscaster cut to DCI Hussein standing on the pavement at the entrance to the police station. Frieda’s photograph appeared once more and a number for members of the public to call. Then the report changed to footage of a royal visit to a London primary school. Frieda just stared for a few seconds at a group of very small children performing a folk dance in their playground. She got up.