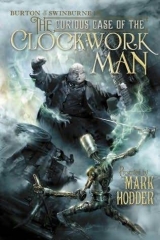

Текст книги "The curious case of the Clockwork Man"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанр:

Детективная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“I dispute that!” said Hawkins. “The colonel made a slip of the tongue while feeling unwell, that's all.”

“Be that as it may, two individuals who were in the service of the family before Sir Roger sailed for South America have confirmed that this man is who he says he is. Need I remind you that he was also recognised by his own mother?”

“Motherrrrr-” the Claimant moaned, gazing blankly at Hawkins.

“Those present who oppose my client never even knew Sir Roger,” Kenealy continued. “It doesn't take a court of law to see where the power lies, does it?”

“By God! What kind of lawyer are you?” Hawkins cried.

“Mr. Hawkins,” Kenealy snarled, “there is a certain degree of decorum demanded by the bar which, once we oppose each other before a judge, will prevent me from saying that which I now wish to say: to wit, shut your damned mouth, sir! You are in no position to criticise and in hardly any state to oppose. I will, against my better judgement, allow you and Colonel Lushington to remain in this house as my client's guests until such a time as the law deems your presence here indefensible. I will then throw you out, and if I have to put my boot to the seat of your pants, then I most certainly shall do so. In the meantime, Detective Inspector Trounce is welcome to stay here until his investigation is done. As for you two-” he turned to Burton and Swinburne “-you can depart forthwith. Your presence is neither required nor desired.”

“Kenealy!” Hawkins yelled. “How dare you! This is an absolute outrage!”

“I am the prosecuting lawyer, Hawkins!” Kenealy roared, his face turning purple and the veins pulsing on his forehead. “I'm well aware that you intend to countersue, but you haven't filed the case yet, and until you do, there's not a damned thing you can do to oppose my client's wishes-and his wishes, at this moment, are that Burton and Swinburne get the hell off his estate!”

Hawkins opened his mouth to reply but was interrupted by Burton: “It's quite all right, Mr. Hawkins. We'll leave. We don't want to contribute to what is obviously already a tense situation.”

“Yaaas,” the Claimant drawled. “Go now.”

Without another word, Burton took Swinburne by the arm and steered him out of the room.

“Sir Richard!” Hawkins called as the two men crossed the threshold. Burton looked back, met the lawyer's eyes, and gave a slight shake of his head.

As they climbed the stairs to their rooms, Swinburne said: “Well, that's that. I'd say our job here is done.”

“You really think we just met the real Sir Roger?” Burton asked.

“Don't you?”

“Absolutely not!”

“Really? What on earth is there to be suspicious about?”

“Are you serious, Algy?”

“Yes.”

“You don't think it odd that Sir Roger was five foot eight at most, and very slim, whereas the Claimant is pushing seven foot tall and is probably the most obese individual I've ever set eyes on?”

“I suppose life in Australia can change a man, Richard. Anyway, there's no reason for us to stay, is there? Shall we return to London?”

“In due course.”

Thirty minutes later, as Burton was packing his portmanteau, Trounce knocked at his bedroom door, entered, and cried: “What the devil are you playing at? Why are you scarpering?”

“We're not. Algy and I are going to get rooms at the Dick Whittington Inn in Alresford,” the king's agent replied. “And you? How long do you expect to stay?”

Trounce blew out a breath. “Phew! What can I do? How does a man go about investigating ghosts? No, Captain, I'll return to the Yard this evening and we'll see what Commissioner Mayne has to say about the whole sorry business.”

“In that case, would you do me a favour and get a message to Herbert Spencer? I need him to let us back into the house and into the pantry. One way or another, we have to find our way through that secret door. I'm convinced the diamond is beyond it and I want to get to it before the ghost does. Tell him to meet Algy and me by the lake at three in the morning.”

Trounce shook Burton's hand. “Very well. Good luck, Captain.”

“The bloomin’ door is open, Boss!” Herbert Spencer whispered. “But it weren't me what opened it!”

He glanced around nervously. The mist was rolling down the slope again, creeping toward the lake, and he wasn't happy.

The giant swans, as yet unnoticed by Kenealy and his client, were sleeping on the mirror-smooth water, their heads resting on their backs, beaks tucked under their wings.

Spencer, Burton, and Swinburne were crouched under a crooked willow.

“Open?” Burton hissed.

“Yus. I checked it afore comin’ out, an’ blow me down with a feather if the back wall weren't sunk right into the floor!”

“And what was beyond it?”

“A tunnel.”

“Take us there, Herbert. We must hurry!”

Keeping their heads low, the three men ran up the slope to the back of Tichborne House. Despite the hour, lights were burning on the ground floor. They skirted the patio and followed Spencer around the corner to the left side of the building, where the door to a coal cellar stood open.

“We'll have to go down the chute, an’ I fear you'll get your togs a bit dirty, gents.”

“That's all right,” Swinburne whispered. “I'm an expert at this sort of thing.”

He was referring to the time he'd spent as an apprentice to Vincent Sneed, the master chimney sweep. The poet had been worked hard and maltreated by his vicious boss, but his experience had been instrumental in Burton's subsequent exposure and defeat of the cabal of scientists who'd been planning to use the British Empire as a subject for social experimentation.

Swinburne swung himself onto the coal chute and slid down into darkness. Burton and Spencer followed him.

They stood, brushed themselves down, and passed through a door into a passage, which they followed past storerooms until they found themselves back at the three pantries. The rightmost one was still empty, its contents stacked in the corridor.

“You go on back to bed, Herbert,” Burton said, keeping his voice low, his eyes fixed on the brick tunnel visible at the back of the small room. “If you don't mind, I'd like you to remain in the house for as long as possible. The Claimant and his lawyer don't know you came with us and will take you for a member of staff. That means you're perfectly placed to keep an eye on things. Any time something of interest occurs, make your way to the Alresford post office and send a message via parakeet to me at 14 Montagu Place.”

“Right you are, Boss!” replied the philosopher. “When you get back to the Smoke, will you tell Miss Mayson that her swans are hale and hearty? She worries about them so.”

“I will.”

“Good luck, gents!”

Herbert Spencer departed.

“Come on, Algy-let's see where this leads.”

The king's agent and his assistant passed through the pantry and entered the tunnel. It was about eight feet in height and the same in width. After a few paces, it angled to the right; then, a few steps beyond, back to the left.

Burton shuddered. He wasn't fond of enclosed spaces, but felt somewhat encouraged when they came to a flaming brand set in a bracket on the wall. By its light, he examined the walls, floor, and ceiling.

“All brick,” he whispered to his companion, “and not so very old. I'd put money on this having been constructed during Sir Henry's time. And look-it definitely runs out in the direction of the Crawls.”

They moved on until they reached a point where the tunnel's brickwork gave way to plain stone blocks.

“Granite,” Burton noted. “We're not under the house anymore. And look how this passage is level, though we know the surface above us slopes upward. It must cut straight through to a structure beneath Lady Mabella's wheat fields.”

“Brrr! Don't mention her! I don't want to see that blasted spook again!”

They crept forward. Burning brands were spaced regularly along the walls.

A few minutes later, they came to a junction and had to choose whether to turn left or right.

“We're probably below the bottom edge of the Crawls now,” Burton observed.

He examined the floor. There was no dust or debris, no footprints, nothing to suggest that anyone had passed.

“What do you think, Algy?”

“When Sir Alfred took us around the Crawls, we went counterclockwise. I say we follow suit, and go right.”

“Jolly good.”

They turned into the right-hand passage and proceeded cautiously along it, listening out for any movement ahead.

Swinburne placed a hand on the left wall, stopped, and pressed an ear against the stone.

“What is it?” Burton asked.

“The wall is warm and I can hear water gurgling on the other side of it.”

“An underground spring. A hot one, too. I thought so. It explains the mist. Let's keep moving.”

As they walked on, Burton measured their progress against his memory of the topography of the surface above. He knew they were following the bottom edge of the Crawls and predicted that the tunnel would turn left a few yards ahead.

It did.

“We're moving deeper underground now,” he observed.

Swinburne cast a sidelong glance at his friend. Burton's jaw was set hard and the muscles at its joint were flexing spasmodically. The famous explorer, who'd spent so many of his younger years traversing vast open spaces, was struggling to control his claustrophobia.

“Not so deep, really,” the poet said encouragingly. “The surface isn't far above.”

Burton nodded and moistened his lips with his tongue, peering into the shadows.

The sound of dripping water punctuated the silence, though they couldn't see any evidence of it. They kept moving until they came to an opening in the left wall.

“We're about halfway along the length of the fields,” the king's agent whispered. “This looks like it'll take us into the middle.”

They stepped into the opening and followed the passage. After a few paces, it suddenly angled leftward, taking them back in the direction of the house. They kept going, eventually reaching a right turn, and, a good few minutes after that, another.

“Now we're going back up the fields,” said Burton, “but this time on their left border.”

When they again reached what he estimated was the halfway mark beneath the fields above, Burton expected to find an opening in the wall to his right. There wasn't one. Instead, the passage continued straight up to the topmost border of the fields then turned left. It continued under the highest point of the Crawls then swerved ninety degrees to the right.

“Back in the direction of the house again!” Burton murmured.

“This is getting ridiculous,” said Swinburne.

The tunnel led them back down to the middle point beneath the edge of the Crawls, turned right, then a few paces later, right again.

“And now back up to the top. We're slowly spiralling inward, Algy. It makes sense. This place follows the design of a classical labyrinth.”

“And here's us without a skein of thread!”

“We don't need one. Labyrinths of this sort are unicursal. Their route to the centre is always unambiguous: just a spiral that folds back in on itself over and over until the middle is reached.”

“Where the minotaur awaits.”

“I fear so.”

Swinburne stopped. “What? What? Not another monster, surely?”

Burton smiled grimly. “No. The same one, I should think.”

“Sir Roger?”

“The Claimant.”

“Yes, that's what I meant.”

Burton looked at the diminutive poet speculatively. “Odd, though, how you keep referring to him as Sir Roger.”

“Merely a slip of the tongue.”

“Like Colonel Lushington's?”

“No! Let's push on.”

The echoing dripping increased as they passed along the stone corridor, which angled back and forth, ever closer to whatever lay at the centre of the structure.

Burton stopped and whispered: “Listen!”

“Water.”

“No, there's something else.”

Swinburne concentrated. “Yes, I hear it. A sort of low hum.”

“B below middle C, Algy. I'll wager it's the diamond, singing like the Choir Stones. That's what sets the piano off-resonance!”

They turned a corner and saw that it was much lighter ahead.

“Careful,” Burton breathed.

They started to walk on their toes.

The sound of running water was loud now, and the droning musical note could be easily heard.

Voices came to them.

One, harsh in tone, said: “Check the walls.”

“Edward Kenealy,” Burton whispered.

“Yaaas, I check,” answered another.

“The minotaur,” Swinburne hissed.

“Hammer on each stone,” Kenealy instructed. “Don't miss an inch. There has to be a cavity concealed here somewhere.”

The king's agent tiptoed forward with Swinburne at his heels. They came to a right-angled turn and peeked around its corner.

Ahead, the tunnel opened onto a large tall-ceilinged square chamber. A stream of water, about two feet wide, fell vertically from a slot in the top of the right-hand wall, cascading into a channel built into the floor. It flowed, steaming, across the middle of the room and disappeared into an opening in the brickwork opposite.

“Tears, that weep within My Lady's round,” quoted Swinburne under his breath.

The humming of the diamond filled the space, seeming to come from everywhere at once, yet the gem was nowhere in sight.

Something pushed through the hair at the nape of the poet's neck. A cold ring of steel touched the top of his spine.

“Hands up!” said a voice.

Swinburne did as he was told.

Burton turned. “Doctor Jankyn,” he said, flatly.

“A bullet will drill through this young man's brain if you try anything, and you wouldn't want that, what!”

“Don't try anything, Richard,” Swinburne advised earnestly.

They heard Kenealy call: “What's going on?”

“A couple of uninvited guests,” Jankyn replied.

“Bring them here!”

“Move into the chamber, gentlemen,” the physician ordered. “Keep your hands where I can see them, please.”

They obeyed.

“Burton,” the Tichborne Claimant grunted as the king's agent stepped into view. “Bad man.”

“And a trespasser,” Kenealy added. “What are you playing at, sir? I ordered you to leave the estate.”

“I had unfinished business to attend to.”

“As we observed. Rather stupid of you to leave the contents of the pantry piled up in the kitchen. Bogle brought it to my attention.”

“How did you open the door?”

“I found a lever in the left-hand room-a shelf that slides sideways and twists upward.”

“I was a fool to miss it.”

“You had no right to be nosing around. I should have you arrested.”

“Arrested,” drawled the mountain of flesh standing in the centre of the chamber. The Claimant surveyed Burton with mindless eyes.

“Try it,” the king's agent challenged.

“Why are you meddling?” Kenealy demanded. “You're a geographer, sir! An explorer! A Livingstone! What has this affair to do with you?”

Burton ignored the question, especially the Livingstone reference, and pointed nonchalantly at the Claimant.

“Who-or should I ask what -is that, Kenealy?”

“It's Sir Roger Tichborne.”

“We both know that's not true, don't we?”

“I insist that it's Sir Roger Tichborne.” The lawyer looked past Burton. “Is that not so, Doctor Jankyn?”

“Absolutely!” said the physician.

“And what do you think, Mr. Swinburne?” Kenealy asked.

“Me? I think my arms are aching. May I lower them?”

“Yes. Step away from him, Jankyn, but keep your pistol steady. If our guests misbehave, shoot to kill.”

“Thank you,” Swinburne said. “And may I say, you're an absolute charmer, Mr. Kenealy.”

“Answer my question. Is this, in your opinion, Sir Roger Tichborne?”

Swinburne hesitated.

“I think-”

He raised a hand to his head and winced.

Burton watched his assistant carefully.

“I think-”

The Claimant let loose a bubbling chuckle.

“I think,” the poet groaned, “that-he is-is probably-Tichborne.”

“Ah. There we have it.” Kenealy smiled.

“Are you quite all right, Algy?” Burton asked.

“Yes. No. Yes. I-my head hurts.”

“Sir Roger,” the lawyer said, turning to the Claimant, “there is an intruder on your property. You have every right to protect your interests.”

“Protect!” the Claimant rumbled. He lumbered forward. “Protect!”

“Kenealy!” Burton snapped. “There is no need to-”

The Claimant's elephantine body blocked his view of the chamber. A meaty hand shot out and grasped the lapels of Burton's jacket and shirt. Cloth ripped as the fingers closed.

Burton was hauled off his feet, swung around, and thrown with tremendous force clear across the room. He slammed into a wall, bounced from it, and landed in a loose-limbed heap on the floor.

“Sir Roger!” Swinburne cried. “Don't!”

“Heh heh!” the Claimant gurgled. He shuffled over to the prone man.

“Perfectly legal, of course,” Kenealy observed.

“I say! He's a jolly strong bounder, what!” Jankyn exclaimed as Burton was hoisted over the Claimant's head and thrown back across the chamber.

“He is, Doctor,” Kenealy agreed. “Life in the colonies does that to a man, even if he was born an aristocrat.”

Burton rolled, reached into his jacket pocket, and pulled out his pistol. As the light from the burning torches pushed the Claimant's vast shadow across him, he raised the weapon and pulled the trigger. The shot was deafening in the enclosed space and everyone flinched. A hole appeared in the cloth stretched across his assailant's belly, but no blood flowed and the bullet appeared to have little effect.

“Baaad man,” the Claimant moaned, reaching down.

The gun was wrenched from Burton's fingers and flung away.

“Leave him alone!” Swinburne pleaded as Burton was gripped by the neck and jerked to his feet. “Sir Roger! Think of your family's good name! God! My head!”

Burton launched a ferocious uppercut into his opponent's chin. His fist sank into a wobbling mass of fat. In reply, he was shaken like a rat caught in the jaws of a carnivore. His teeth rattled together. Desperately, he loosed a furious tattoo of blows into the gargantuan body, hammering it around the ribs, but he might have been punching a pillow for all the damage he did; the rib cage was buried deep beneath layers of blubber. The Claimant took the assault without so much as a groan.

Squirming out of the creature's grasp, Burton ducked under groping hands and, like a whirlwind, dealt out roundhouse punches that should have rocked his opponent on his heels. It was useless.

The Claimant lunged and swept his arms around Burton's shoulders. The king's agent felt them tighten and tried to slip downward, but the creature held him with the strength of a grizzly bear. Terrible agony shot through the explorer's chest and it felt as if every bone in his torso must splinter.

It was not the embrace of a human being. Beneath the thick jellied padding flexed the tremendous muscles of a predatory beast.

Pain exploded in Burton's back and his lower spine creaked audibly. Blood pounded in his ears as the awful constriction increased. The monotonous tone of the diamond was filling his head. His legs flopped uselessly and, when the Claimant lifted him from the floor, his feet dangled as loosely as a rag doll's.

Swinburne looked on helplessly as his friend was hoisted up over the creature's head, ready to be dashed against the wall once again.

“Tell me, Swinburne!” Kenealy said. “You don't happen to know where Sir Henry concealed that black diamond of his, do you?”

“No,” the poet whimpered. “Except that-”

“Yes?”

The Claimant swung Burton back to fling him into the air. As he did so, a spark of vitality flared in the explorer's dimming consciousness and, with a desperate effort of will, he put all the strength he could muster into a jab, hooking his stiffly held fingers down into his opponent's right eye.

The creature let loose a howl and dropped him. Burton hit the ground at the Claimant's feet.

“Except the poem,” said Swinburne.

“Poem, sir? What poem is that?”

“Algy, don't,” Burton croaked.

“The tears, that weep within My Lady's round,” Swinburne proclaimed. “Do you mind if I sit down? I have the most dreadful headache.”

“Please, be my guest.” Kenealy grinned. His glasses magnified his little red-rimmed eyes.

Jankyn strode over to Burton and looked down at him. “My goodness. He doesn't look at all well!”

“I bow to your expertise, Doctor,” Kenealy said. “Sir Roger, be careful! Don't break him! You may be defending yourself against a ruthless intruder but a charge of manslaughter would be most inconvenient at present. Tears, Mr. Swinburne?”

“I can't help it. It's the pain. My brain is afire!”

“I was referring to the poem.”

“Oh, that gobbledygook. The diamond's behind the waterfall, obviously.”

The Claimant bent to pick Burton up. The explorer quickly drew in his legs and kicked his booted feet into the fat man's face. His left heel caught one of the seven lumps that circled the bloated thing's skull, ripping open the little line of stitches.

The Claimant's head snapped back.

“Ouch! Hurt me!” he complained, clutching Burton's arm and dragging him upright.

The king's agent caught sight of a black diamond glittering inside his opponent's wound.

“Choir Stone!” he mumbled.

A massive fist crashed into his face.

He looked up at the off-yellow canvas of his tent.

The exhaustion and fevers and diseases and infections and wounds ate into his body.

There was not a single inch of him that didn't hurt.

“Bismillah!”

No more Africa. Never again. Nothing is worth this agony. Leave the source of the Nile for younger men to find. I don't care anymore. All it's brought me is sickness and treachery.

Damn Speke!

Don't step back. They'll think that we're retiring.

How could he possibly have interpreted that order as a personal slight? How could he have so easily used it as an excuse for betrayal?

“Damn him!”

“Are you awake, Richard?”

“Leave me alone, John. I need to rest. We'll try for the lake tomorrow.”

“It's not John. It's Algernon.”

Algernon.

Algernon Swinburne.

The yellowed canvas was yellowed plaster-a smoke-stained ceiling.

Betrayal. Always betrayal.

“Algy, you told them where to find it.”

“Yes.”

“Was the diamond there?”

“Yes. Kenealy reached through the waterfall. There was a niche behind it. He pulled out the biggest diamond I've ever seen, black or otherwise. It was the size of a plum.”

Betrayal.

To hell with you, Speke! We were supposed to be friends.

Is there shooting to be done?

I rather suppose there is.

Voices outside the tent. War cries. Running footsteps, like a sudden wind. Clubs beating against the canvas.

A world conceived in opposites only creates cycles and ceaseless recurrence. Only equivalence can lead to destruction.

“And final transcendence.”

“What? Richard, are you still with me?”

“Be sharp, and arm to defend the camp.”

“Richard. Snap out of it! Wake up!”

“Algy?”

“I'm sorry, Richard. Truly, I am. But I couldn't help it. Something got inside my head. I can't explain it. For a few moments, I really believed that monstrosity was Roger Tichborne.”

“Get out, Algy. If this blasted tent comes down on us we'll be caught up good and proper!”

“Please, Richard. We're not in Berbera. This is the Dick Whittington Inn. We're in Alresford, near the Tichborne estate.”

“Ah. Wait. Yes, I remember. I think the malaria has got me again.”

“No, it hasn't. It was the Claimant. That confounded blackguard beat you half to death. You remember the labyrinth?”

“Yes. Gad! He was strong as an ox! How serious?”

“Bruises. Bad ones. You're black-and-blue all over. Nothing broken, except your nose. You need to rest, that's all.”

“Water.”

“Wait a minute.”

The labyrinth. The stream. The Claimant.

The Cambodian Choir Stones!

The Claimant has Brundleweed's stolen diamonds and the two missing Pelletier gems embedded in his scalp. Why? Why? Why?

“Here, drink this.”

“Thank you.”

“I have no memory of how we got here, Richard. The last thing I recall is seeing Kenealy pass the diamond to the Claimant. The creature looked at it, then he looked at me, and suddenly that low hum that comes from it overwhelmed me. I heard a woman's voice behind me, turned, and saw the ghost of Lady Mabella. I must have passed out. I woke up here a little while ago. The landlord says we were delivered in a state of intoxication by staff from the estate. I found a letter addressed to us on your bed. Listen: Burton, Swinburne, Against my client's express instruction, which was issued through me, his lawyer, in front of witnesses, you chose to trespass on the Tichborne estate and you attempted to steal Tichborne property. Were it not for the fact that we are already preparing a complex legal case against Colonel Lushington, I would not hesitate to prosecute you. As it is, my client has agreed to let this matter drop on the condition that you make absolutely no further attempt to intrude upon Tichborne property. I remind you that the law states that trespassers may be shot on sight. If you set foot on the estate again and somehow manage to avoid such a fate, I assure you that you will not avoid the full force of the law. Doctor Edward Vaughan Hyde Kenealy On behalf of Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne

“It bears Kenealy's signature and, believe it or not, what looks to be the Claimant's thumbprint. It's also witnessed by Jankyn and the butler, Andrew Bogle.”

“That's that, then.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean there's nothing more we can do here, Algy. Kenealy and the Tichborne Claimant are obviously in league with the ghost of Lady Mabella, and they are now in possession of the South American Eye and the fragments of the Cambodian Eye. So we'll pack up and return to London, we'll investigate the Claimant's background, and we'll watch carefully to see what our enemies intend to do with those peculiar stones.”

S ir Richard Francis Burton had been in South America for three weeks. He was unshaven and his skin was dark and weather-beaten. He looked untamed and dangerous, like a bandit.

“Difficult times, Captain,” said Lord Palmerston softly as the king's agent sat down.

Burton grunted an agreement and studied the prime minister's waxy, eugenically enhanced features. He noticed that the man's mouth seemed to have been stretched a little wider and there were new surgical scars around the angles of his jaw, a couple of inches beneath the ears. They were oddly gill-like.

He looks like a blessed newt!

The two men were in number 10 Downing Street, the headquarters of His Majesty's government.

“How goes the war, sir?” he asked.

“President Lincoln has formidable strategists directing his army,” Palmerston responded, “but mine are better, and, unlike his, they aren't defending two fronts. Our Irish troops have already taken Portland and large sections of Maine. In the south, Generals Lee and Jackson have forced the Union out of Virginia. I wouldn't be at all surprised to receive Lincoln's surrender by Christmas.”

A great many people, Burton included, held the Eugenicist faction of the Technologist caste responsible for Great Britain's entry into the American conflict. Had the scientists left Ireland alone, it was argued, there would not have been such an overwhelming refugee problem; and if there had not been an overwhelming refugee problem, then Palmerston may have reacted rather less aggressively to the Trent Affair.

The Eugenicists had started sowing seeds in Ireland last March, around the time of the Brundleweed robbery.

It was an attempt to put an end to the Great Famine, which had been devastating the Emerald Isle since 1845. Nearly two decades of disease had obliterated the potato crop before spreading to other flora, leaving the island a virtual desert. The source of the blight remained a mystery, though its failure to cross to mainland Britain suggested a disease of the soil.

The Eugenicists, working with the botanist Richard Spruce, had planted specially adapted seeds at twelve test sites. These germinated within hours and the plants grew with such unexpected rapidity that they were fully mature within a fortnight. By the end of April, they'd blossomed and pollinated. During May, their seeds and spores spread right across the country, and by early July, from shore to shore, Ireland was a jungle.

Inexplicably, the plants confined themselves to the island; their seeds wouldn't germinate anywhere else. This was a stroke of luck, for, as with every other Eugenicist experiment, the benefits were accompanied by an unexpected side effect.

The new flora was carnivorous.

The experiment was an unmitigated disaster.

During June and July, more than fifteen thousand people were killed. Venomous spines were fired into them, or tendrils strangled them, or acidic sap burned away their flesh, or flowery scent gassed them, or roots jabbed into their bodies and sucked out their blood.

The scientists were at a loss.

Ireland became uninhabitable.

Its population fled.

During the middle months of summer, mainland Britain struggled with a massive influx of refugees. Wooden shanty towns were set up to house them in South Wales, along the edges of Dartmoor, in the Scottish Highlands, and on the Yorkshire Moors. They quickly deteriorated into disease-ridden slums-scenes of terrible squalor, violence, and poverty.

Lord Palmerston's solution to the problem was both ingenious and very, very dangerous.

In his mind's eye, Burton could picture the prime minister contemplating two reports, one entitled The Irish Crisis and the other The Trent Affair, and could imagine the glint in his eyes as a radical and daring scheme occurred to him.

The Trent Affair had begun the previous December, when two Confederate diplomats, John Slidell of Louisiana and James Mason of Virginia, had been dispatched to London to convince Palmerston that an independent Confederacy would establish a mutually beneficial commercial alliance with Great Britain. They'd been travelling on the British mail packet Trent when the Union ship USS San Jacinto intercepted it. The British vessel was boarded, searched-not without some rough handling-and the envoys taken prisoner.

This was viewed, right across Europe, as an outrageous insult and a blatant act of provocation.

Angrily, Palmerston demanded an apology from the Union.

While he awaited President Lincoln's response, he ordered the army to begin amassing its troops on the Canadian border and the Royal Navy to prepare for attacks on American shipping the world over.

Toward the end of January, Lincoln's secretary of state responded by setting Slidell and Mason free and by explaining, in a letter, that the interception and searching of the Trent, while conducted in an unfortunate manner, had, in fact, been perfectly legal according to maritime law.