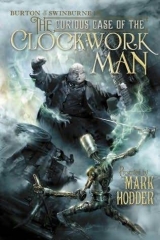

Текст книги "The curious case of the Clockwork Man"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанр:

Детективная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Burton froze with a forkful of beef half raised to his mouth.

“Richard?” Swinburne enquired, puzzled by his friend's expression.

Burton lowered the fork. “Do you think I might see the kitchen and pantries at some point?” he asked.

“Of course,” said Tichborne. “Why? Do you take an interest in cooking?”

“Not at all. It's the architecture of the house that fascinates me.”

“The cook and her staff will be cleaning up now, after which it'll be a little late. What say you we go down there tomorrow morning before the Claimant shows up?”

“Thank you.”

They finished eating.

Tichborne stood and swayed slightly.

“I'd much appreciate a few rounds of billiards,” he said. “Will you gentlemen join me?”

“Sir Alfred-” Doctor Jankyn began, but the baronet stopped him with a sharp gesture.

“Don't fuss, Jankyn. I'm perfectly fine. Join us.”

They repaired to the billiard room. Hawkins began a game with Swinburne and was surprised to find the poet a formidable opponent.

Bogle served port and sweet sherry.

Lushington put a flame to a meerschaum pipe, and Jankyn lit a briar, while Burton, Hawkins, and Tichborne all opted for cigars. Within minutes, the room was thick with a blue haze of tobacco smoke.

“By golly, it's a veritable drubbing!” the lawyer exclaimed as Swinburne potted three balls in quick succession.

“If only you were as accurate with a pistol!” Burton whispered to his friend.

“To be perfectly honest,” Swinburne replied, grinning, “I'm not hitting the balls I'm aiming at. It's sheer luck that the ones I am hitting are going in!”

He won the game against Hawkins, then played Colonel Lushington and beat him, too.

Sir Alfred took up a cue. “I'll be the next lamb to the slaughter,” he announced, and they began the game.

As Burton watched, he became aware that he was feeling oddly apprehensive, and when he looked at the others’ faces, he could see they were experiencing the same sensation: the inexplicable presentiment that something was going to happen.

He shook himself and emptied his glass in a single swallow.

“Another port, please, Bogle.”

“Certainly, sir.”

“You might open the window a crack, too. It's like a London pea-souper in here.”

“I would, sir, but it's worse outside.”

“Worse? What do you mean?”

“It's the mist, sir. It's risen unusually high tonight-quite suddenly, too. Right up to the second storey of the house, and thicker than I've ever seen it.”

Burton crossed to the window and drew aside the curtain. The room was brilliantly reflected in the glass, and he could make out nothing beyond. Twisting the catch open, he drew up the sash a little, bent over, and peered through the gap. A solid wall of white vapour collapsed inward and began to pour over the sill and into the room.

Hurriedly, he closed the window and pulled the curtain across it.

Behind him, the room fell silent.

A glass hit the floor and shattered.

He turned.

Swinburne, Lushington, Hawkins, Jankyn, Tichborne, and Bogle were all standing motionless. Even through the blue haze, he could see that the blood had drained from their faces. They were staring wide-eyed at a corner of the room.

Burton followed their gaze.

There was a woman there-or, rather, a column of denser tobacco smoke that had taken on the form of a thickset, heavy-hipped female.

She raised a nebulous arm and pointed a tendril-like finger at Sir Alfred Tichborne. Black eyes glared from her head.

Tichborne shrieked and backed away until he was pressed against the wall, banging into a rack of billiard cues which clattered noisily to the floor.

“Lady Mabella!” he moaned.

To either side of him, the haze suddenly congealed, forming two ghostly, indistinct, top-hatted figures. They wrapped transparent fingers around his arms.

“Bloody hell!” Hawkins breathed.

Bogle let loose a piercing scream, dropped to his knees, and covered his eyes.

“For God's sake, help me!” Tichborne wailed.

Before any of the men could move, the wraiths had dragged the baronet across the room. Lady Mabella surged forward, wrapped her swirling arms around him, and plunged through the door, taking him with her. The door didn't open, nor did it smash; the ghostly woman, wraiths, and man simply disappeared through the wood as if it were nothing but an illusion.

A muffled cry came from the corridor beyond: “Save me! Oh, Christ! They mean to kill me!”

“After him!” Burton barked, breaking the spell that had immobilised them all.

In three long strides, he reached the door and wrenched it open in time to see Tichborne being hauled through another at the far end of the passage. Again, the flesh-and-blood baronet passed straight through the portal without it opening or breaking.

Burton hurtled along the hallway with the others trailing behind, threw open the door, and ran into the drawing room.

Tichborne's terrified eyes fixed on him.

“Burton! Please! Please!”

Lady Mabella levelled her black eyes at the king's agent, and he heard in his mind an accented female voice command: “Do not interfere!”

He stumbled and clutched his head, feeling as if a spear had jabbed into his brain. The pain passed in an instant. When he looked up again, the ghost and Tichborne had vanished through the door leading to the main parlour.

“Are you all right?” Swinburne asked, catching up with him.

“Yes! Come on!”

They burst into the parlour, paced across it, and tumbled into the manor's entrance hall.

The two wraiths, led by Lady Mabella, were pulling Sir Alfred up the main staircase. He screamed and pleaded hysterically.

A gun boomed and plaster exploded from the wall beside him. Burton looked around and saw Lushington with a pistol in his raised hand.

“Don't shoot, you fool!” he shouted. “You'll hit the baronet!”

He started up the stairs.

Sir Alfred was dragged around a corner, his cries echoing through the house.

Burton, Swinburne, and the others followed the fast-moving wraiths down the hallway leading to the rear of the mansion, through the morning room, into a small sitting room, then to a dressing room, and into the large bedchamber beyond.

Burton stumbled into it just as Lady Mabella gripped Tichborne around the waist and disappeared with him through the closed window. His body passed through the glass without shattering it. A short scream of terror from outside ended abruptly.

The two wraiths hovered before the glass. One of them turned, reached up, and raised its phantom top hat. The figures dissipated.

Stepping to the window, Burton slid it up and looked out. About three feet below, swells of impenetrable white mist rose and fell like liquid.

“Jankyn!” he bellowed, spinning on his heel. “Follow me! The patio! Quickly, man!”

The physician, who'd been lagging behind the others and had only just entered the room, found himself being tugged along, back down the stairs, and through the house to its rear. The rest of them followed.

“What's happening?” Lushington demanded. “Where's Sir Alfred?”

“Come!” Burton called.

They entered the hunting room and the king's agent pulled open the door to the patio. Dense mist enveloped the men as they stepped outside.

“I can't see a thing!” said Jankyn.

“Over here.”

Burton knelt beside Sir Alfred Tichborne, who lay broken upon the pavement, blood pooling from the back of his head.

Jankyn joined them.

“He was thrown from the window,” Burton explained.

Tichborne looked up at them, blinked, coughed, and whispered: “It hurts, Doctor Jankyn.”

“Lie still,” the physician ordered.

Sir Alfred's eyes held Burton's. “There's something-” He winced and groaned. “There's something I want-I want you to-do.”

“What is it, Sir Alfred?”

A tear slid from the baronet's eye. “No matter who claims this-this estate tomorrow, my brother-my real brother-he and I were the last Tichbornes. Don't allow anyone else to-to take the name.”

He closed his eyes and emitted a deep sigh.

Jankyn leaned over him. He looked back at Burton.

“Sir Alfred has joined his mother.”

Even though it was near enough midnight, Burton took a horse and trap and galloped to Alresford, where he hammered on the door of the post office until the inhabitants opened a window and demanded to know what in blue blazes he thought he was bally well doing. Displaying the credentials granted to him by the prime minister, he quickly gained access to the aviary and gave one of the parakeets a message for the attention of Scotland Yard.

Early the next morning, an irregular ribbon of steam appeared high over the eastern horizon and arced down toward the estate. It was generated by a rotorchair, which landed with a thump and a bounce and skidded over the gravel on the carriageway in front of Tichborne House.

A burly figure clambered out of it, pulled leather-bound goggles from his eyes, and was mounting the steps to the portico when the front door opened and Burton emerged.

“Hello, Trounce. Glad to see you!”

They shook hands.

“Captain, please tell me the parakeet was joking!”

“Joking?”

“It told me murder had been done-by ghosts!”

“As bizarre as it sounds, I'm afraid it's true; I saw it with my own eyes.”

Trounce sighed and ran his fingers through his short, bristly hair.

“Ye gods, how the devil am I supposed to report that to Commissioner Mayne?”

“Come through to the parlour, I'll give you a full account.”

Some little time later, Detective Inspector Trounce had been introduced to Colonel Lushington, Henry Hawkins, and Doctor Jankyn, and had taken a statement from each of them. He then examined Sir Alfred's body, which lay in a small bedroom, awaiting the arrival of the county coroner.

Trounce settled in the smoking room with Burton and Swinburne.

“It's plain enough that he was killed by the fall,” he muttered. “But how am I to begin the investigation? Ghosts, by Jove! It's absurd! First Brundleweed and now Tichborne!”

“That's a very interesting point,” Burton said. “We can at least establish that the two crimes are linked-beyond the presence of a ghost, I mean.”

“How so?”

“We dismissed Brundleweed's spook as either imagination or a gas-induced hallucination. However, last night I witnessed ghosts pulling poor Sir Alfred straight through solid matter. It strikes me that if they can do that with a man, then they can certainly do it with diamonds.”

“You mean to suggest that, some little time before Brunel's clockwork raiding party arrived, Brundleweed's ghost reached into his safe and pulled the Francois Garnier gems right out, replacing them with onyx stones, all without even opening the door?”

“Yes. Exactly that.”

“And was it the Tichborne ghost, Captain? This Lady Mabella?”

“It would be fair to assume so. The motive appears to be the same; she has an interest in black diamonds. There's rumoured to be one, of the same variety as the Choir Stones, concealed somewhere on this estate. Lady Mabella has spent night after night knocking on the walls around the house. What does that suggest to you?”

“That she's been searching for a secret hiding place?”

“Precisely-although it's strange that she should knock on walls when she has the ability to walk right through them. That aside, we appear to have a diamond-hungry spook on our hands. I propose that our priority should be to discover the stone before she does; perhaps then we can find out why it's so important to her.”

Trounce rubbed his hands over his face, his expression a picture of exasperation. “Fine! Fine! But it beats me why a diamond should be of any blessed use to a ghost!”

“As I say, my friend, that is the crux of the matter.”

“And why murder Sir Alfred?”

“Perhaps to make way for the Claimant?”

Algernon Swinburne clapped his hands together. “Dastardly!” he cried. “The witch and the imposter are hand-in-glove!”

Trounce groaned. “I was the laughing stock of the Yard for decades because I believed in Spring Heeled Jack. Lord knows what mockery I'm letting myself in for now, but I suppose we'd better get on with it. Where do we start?”

“In the kitchen.”

“The kitchen? Why the kitchen?”

“Of course!” Swinburne enthused, as realisation dawned. “Mrs. Picklethorpe's snoring!”

Trounce looked from the king's agent to the diminutive poet and back again.

“You know, I could easily grow to dislike you two. What in the devil's name are you jabbering about?”

“We have Herbert Spencer the vagrant philosopher with us,” Burton explained. “He's staying down in the servants’ quarters. He complained that the cook snores, and that the sound reverberates through the walls. Perhaps it's because the walls are hollow.”

“And there's a dreadful old family poem,” Swinburne added, “which says Consume if thou wouldst uncover. We think the diamond is hidden somewhere under the two wheat fields at the front of the house. Initially, we speculated that the doggerel was instructing whoever wanted to find it to get rid of the crop and dig, but perhaps there's an easier way.”

“You mean a secret passage from the kitchen?” Trounce asked.

“Or, more specifically, from one of the famous pantries,” Burton responded.

“Gad!” Trounce exclaimed. Then again: “Gad!”

“The Claimant is due here soon, so I suggest we have a poke around straightaway. I don't know how welcome we'll be in the manor once he sets foot in it.”

Trounce jerked his head in agreement.

They left the smoking room and sought out Colonel Lushington, who they found pacing in the study, next to the library.

He looked up as they entered. “More news,” he announced. “Bad. Maybe good. Not sure. Could be either. Depends how it goes. Hawkins is of the opinion that it'll be a civil trial: Tichborne versus Lushington.”

“Why so?” Burton asked.

“The Claimant, under the name Roger Tichborne, will contest my right to act on the family's behalf. He'll try to have me removed from the house. Ejected. Out on my ear, so to speak. However, if he's not Roger Tichborne, we'll counter by suing for a criminal trial. Court. Jury. So forth. King versus Claimant. ”

“Good!” Trounce grunted. “That would bring Scotland Yard in on the matter.”

Lushington agreed. “High time. I'd certainly like to know more about what the Claimant fellow got up to in Australia when he was calling himself Tomas Castro!”

“Rest assured, Colonel, the moment it becomes a criminal matter, the Yard will send someone to the colonies.”

Burton interrupted: “Colonel, it may seem trivial and badly timed but, as I mentioned last night, I have good reason for wanting to examine the kitchens. I assure you it's relevant to this whole affair. Would you mind?”

Lushington looked puzzled but nodded. He summoned Bogle and told him to take Burton, Swinburne, and Trounce “below stairs.”

They found that the basement of the manor was divided into a great many small rooms. There were the servants’ sleeping quarters, sitting rooms, and washrooms, storerooms, coal cellars, sculleries, and a dining room. The kitchen was by far the largest chamber, and it opened onto three pantries, all stocked with cured meats, jars of preserved comestibles, sacks of flour, dried beans and sugars, cheeses, oils, and vinegars, vegetables, kegs of beer, and racks of wine.

“Let's take one each,” Burton suggested. “Check the walls and floors. We're looking for a concealed door.”

He stepped into the middle room and began to move sacks and jars aside, stretching over the piled goods to rap his knuckles against the plaster-coated back wall. He heard his colleagues doing the same in the rooms on either side.

As thorough as he was, he found nothing.

“I say, Captain, come and have a look at this!” Detective Inspector Trounce called.

Burton left his pantry and entered the one to the right.

“Got something?”

“Perhaps so. What do you make of that?”

The Scotland Yard man pointed to the top of the back wall, where it abutted the ceiling. Initially, Burton couldn't see anything unusual, but upon closer inspection he noticed a thin, dark line running along the joint.

“Hmm,” he grunted, and heaved himself up onto a beer barrel.

Leaning against the wall, he reached up and ran his thumbnail along the line. Then he stepped down and said: “I'm not the slightest bit peckish, so I'd rather not eat and drink my way through this lot despite the poem's directive. Let's settle for clearing it out into the kitchen.”

He called Swinburne.

“What?” came the poet's voice.

“Come here and lend some elbow grease!”

The three men quickly moved the contents of the pantry out, exposing every inch of the rear wall.

“The line extends down the sides and across the base of the wall,” Burton observed.

“A door?” asked Swinburne.

“I can't see any other explanation. There's no sign of a handle, though.”

Trounce placed both his hands against the wall and pushed.

“Nothing,” he grunted, stepping back.

The three men spent the next few minutes pressing different parts of the barrier. They then examined the rest of the small room in the hope of finding a lever or switch of some sort.

“It's hopeless,” the inspector grumbled. “If there's a way to get that blasted door open, it's not in here.”

“Perhaps we've overlooked something in the poem,” Swinburne mused.

“Possibly,” answered Burton. “For the moment, we'd better get back upstairs. We don't want to miss the Claimant's grand entrance. We'll return later. Algy, go and track down Herbert and tell him what's what. He can be poking about down here while we're occupied. I'll ask the cook to leave this room as it is for the time being.”

Some little time later, the king's agent and his companions joined Colonel Lushington, Hawkins, and Jankyn in the library. It was just past midday.

The colonel, twisting the points of his extravagant muttonchops, paced up and down nervously.

“Mr. Hawkins,” he said, “tell me more about this Kenealy fellow.”

“Who's Kenealy?” Burton asked.

“Doctor Edward Vaughan Hyde Kenealy,” said Hawkins. “He's the Claimant's lawyer. He also considers himself a poet, literary critic, prophet, and would-be politician. He's a through-and-through Rake-a member of the inner circle thought to have gathered around the new leader, whoever that may be.”

“Well now!” Burton exclaimed. “That's very interesting indeed!”

Laurence Oliphant and Henry “The Mad Marquess” Beresford had formerly led the Rakes, but both had been killed by Burton last year, and the faction had been in disarray for some months.

“Not John Speke, surely!” Burton muttered to himself. Recent events would make a lot more sense if Speke was guiding the Rakes and using them to get at the black diamonds, but, somehow, Burton just couldn't see it. His former partner didn't possess leadership qualities, and furthermore, he was extremely conservative and repressed in character-not at all representative of the Rake philosophy.

Burton wondered whether he'd be able to prise some information out of the Claimant's lawyer.

“Interesting is not a word I'd use to describe Edward Kenealy, Sir Richard,” Henry Hawkins was saying. “Barking mad would be my choice. He's as nutty as a fruitcake, and a confounded brute, too. Ten years ago, he served a month in prison on a charge of aggravated assault against his six-year-old illegitimate son. The boy had been beaten half to death and almost strangled. Kenealy has since been accused-but not charged-with a number of assaults against prostitutes. He's a very active follower of the Marquis de Sade and adheres to the belief that inflicting pain weakens social constraints and liberates the spirit.”

Detective Inspector Trounce eyed Algernon Swinburne, who frowned back and muttered: “Some are givers, some are takers, Inspector.”

Hawkins continued: “He also subscribes to a rather incoherent theology which claims that a spiritual force is beginning to change the world-that we currently exist on the borderline between two great epochs, and the transformation from one to the other will cause a social apocalypse, overthrowing the world's ruling elite and passing power, instead, into the hands of the working classes.”

Burton shifted uneasily, remembering Countess Sabina's prophecy and his subsequent strange dream.

Hawkins went on: “He's published a number of long-winded and nonsensical texts to promote this creed but, if you ask me, the only useful information one can draw from them is the fact that their author is an egomaniac, fanatic, and fantasist. All in all, gentlemen, a very dangerous and unpredictable fellow to have as our opponent.”

“And one who's currently travelling down the carriageway, by the looks of it, what!” Jankyn noted from where he stood by the window. “There's a growler approaching.”

Lushington blew out a breath and rubbed his hands on the sides of his trousers. “Well, Mr. Hawkins-ahem!-let's go and cast our eyes over, that is to say, have a look at, the man who says he's Roger Tichborne. Gentlemen, if you'd be good enough to wait here, I'll introduce the Claimant and his lunatic lawyer presently.”

The two men left the room.

Swinburne crossed to the window just in time to see the horse-drawn carriage pass out of sight as it approached the portico.

“What do you think?” he asked Jankyn quietly. “Swindler or prodigal?”

“I'll reserve my judgement until I see him and he makes his case, what!”

Burton, who was standing beside one of the large bookcases with Detective Inspector Trounce, caught his assistant's eye.

With a nod to Jankyn, the poet left the window and walked over to the explorer, who pointed to a leather-bound volume. Swinburne read the spine: De Mythen van Verloren Halfedelstenen by Matthijs Schuyler.

“What of it?” he asked.

“This is the book that tells the myths of the three Eyes of Naga.”

“Humph!” the poet muttered. “Circumstantial evidence, I'll grant, but the ties between the Tichbornes and the black diamonds appear to be tightening!”

“They do!” Burton agreed.

Bogle entered carrying a decanter and some glasses. He put them on a sideboard and started to polish the glasses with a cloth, preparing to offer the men refreshment.

The door opened.

Colonel Lushington stepped in and stood to one side. His eyes were glazed and his jaw hung slackly.

Henry Hawkins followed. He wore an expression of shock, and was holding a hand to his head, as if experiencing pain.

“Gentlemen,” the colonel croaked. “May I present to you Doctor Edward Kenealy and-and-and the-the Claimant to the-to the Tichborne estate!”

A man entered behind him.

Dr. Kenealy possessed the same build as William Trounce; he was short, thickset, and burly. However, where the Scotland Yard man was mostly brawn, the lawyer was soft and running to fat.

His head was extraordinary. An enormous bush of dark hair and a very generous beard framed his broad face. His upper lip was clean-shaven, his mouth was wide, and he wore small thick-lensed spectacles behind which tiny bloodshot eyes glittered. The overall effect was that of a wild man of the woods peeking out from dense undergrowth.

He jerked an abrupt nod of greeting to each of them in turn, then said, in an aggressive tone: “Good day, sirs. I present-”

He paused for dramatic effect.

“-Sir Roger Tichborne!”

A shadow darkened the doorway behind him. Kenealy moved aside.

A great mass of coarse cloth and swollen flesh filled the portal from side to side, top to bottom, and slowly squeezed through, before straightening and expanding to its full height and breadth, which was simply enormous.

The Tichborne Claimant was around six and a half feet tall, prodigiously fat, and absolutely hideous.

A towering, blubbery mass, he stood on short legs as thick as tree trunks, which were encased in rough brown canvas trousers. His colossal belly pushed over the top of them, straining his waistcoat to such an extent that the material around the buttons had ripped and frayed.

His right arm was long and corpulent, stretching the stitching of his black jacket, and it ended in a bloated, plump-fingered and hairy hand. The left arm, by contrast, seemed withered below the elbow. It was shorter, and the hand was that of a more refined man, smooth-skinned and with long, slender fingers.

The enormous round head that squatted necklessly on the wide shoulders was, thought Burton, like something straight out of a nightmare. The face, which certainly resembled that of Roger Tichborne, if the portrait in the dining room was anything to go by, appeared to have been roughly stitched onto the front of the skull by means of a thick cartilaginous thread. Its edges were pulled tautly over the flesh beneath, causing the features to distort somewhat, slitting the eyes, flaring the nostrils, and pulling the lips horribly tight over big, greenish, tombstone teeth.

From behind this grotesque mask, dark, blank, cretinous eyes slowly surveyed the room.

The head was hairless, the scalp a nasty spotted and blemished yellow, and around the skull, encircling it entirely like a crown, were seven irregular lumps, each cut through by a line of stitches.

There came a sudden crash as Bogle dropped a glass.

The butler clutched at his temples, grimaced, then, his eyes filling with tears, he said: “My, sir! But how much stouter you are!”

The creature grunted and attempted a smile, pulling its lips back over its decayed teeth and bleeding gums. A line of pinkish drool oozed from its bottom lip.

“Yaaas,” it drawled in a slow, rumbling voice. “I-not-the boy-I was when I leave Tichborne!”

The statement was made hesitatingly, and dully, as if it came from someone mentally impaired.

“Then you recognise my client?” Kenealy demanded of Bogle.

“Oh, yes, sir! That's my master! That's Sir Roger Tichborne!”

“By thunder! What nonsense!” Hawkins objected. “That-that person -may possess a passing likeness in the face but he is blatantly not-not-”

He stopped suddenly and gasped, staggering backward.

“My head!” he groaned.

Colonel Lushington emitted a strangled laugh and dropped to his knees. Doctor Jankyn hurried forward and took the colonel by the shoulders.

“Are you unwell?” he asked.

“Yes. No. No. I think-I think I have a-I'm dizzy. It's just a migraine.”

“Steady!” the doctor said, pulling the military man to his feet. “Why, you can barely stand!”

Lushington straightened, swayed, pushed the physician away, and cleared his throat.

“My-my apologies, gentlemen. I feel-a bit-a bit… If Sir Roger will permit it, I shall-retire to my room to-to lie down for an hour or so.”

“Good idea!” Kenealy said.

“You go,” the Claimant grunted, lumbering into the centre of the room. “You go-lie down now. Feel better. Yes.”

To the other men's amazement, Colonel Lushington, who'd gone from calling the creature “the Claimant” to “Sir Roger” in less than a minute, stumbled from the room.

“What the deuce-?” Trounce muttered.

Doctor Jankyn announced: “He'll be all right after he rests awhile, what!” He turned to the Claimant and extended his hand. “Welcome home, Sir Roger! Welcome home! What a marvellous day this is! I never thought to see you again!”

The Claimant's meaty right hand enveloped the doctor's and shook it.

“So much for reserving judgement!” Swinburne whispered to Burton. “Although he might be right. Maybe this isn't an imposter at all!”

Burton gazed at his assistant in astonishment.

Hawkins shook his head, as if to clear it. He turned to Jankyn.

“You don't mean to suggest that you also recognise this-this-?”

“Why, of course I do!” Jankyn cried. “This is young Sir Roger!”

“It is-good to see you-Mr-Mr-?” the creature rumbled.

“Doctor Jankyn!” the physician supplied.

“Yes,” came the reply. “I remember you.”

Hawkins threw up his hands in exasperation and looked across at Burton, who shrugged noncommittally.

“And who might you gentlemen be, may I ask?” Kenealy enquired, in his brusque, belligerent manner.

“I am Henry Hawkins, acting on behalf of the relatives,” the lawyer snapped, bristling.

“Ah ha! Then advise them to not oppose my client, sir! He has come to take possession of what's rightfully his and I mean to see that he gets it!”

“I think it best we save discussions of that nature for the courtroom, sir,” Hawkins responded coldly. “For now, I'll restrict myself to that which courtesy demands and introduce Sir Richard Francis Burton, Mr. Algernon Swinburne, and Detective Inspector William Trounce of Scotland Yard.”

“And, pray, why are they here?”

Trounce stepped forward and, in his most officious tone, said, “I am here, sir, to investigate the murder of Sir Alfred Tichborne, and I advise you not to interfere with my duties.”

“I have no intention of interfering. Murder, is it? When did this occur? And how?”

Trounce shifted his weight from one foot to the other. “Last night. He fell from a window under mysterious circumstances.”

“My-brother?” the Claimant uttered.

“That is correct, Sir Roger,” said Kenealy, turning to the monstrous figure. “May I be the first to offer my condolences?”

“Yes,” the Claimant grunted, meaninglessly.

Kenealy looked back at Trounce. “Why murder? Why not an accident or suicide?”

“The matter is under investigation. I'll not be drawn on it until I have gathered and examined the evidence.”

“Very well. And you, Sir Richard-is there a reason for your presence?”

Burton glowered at the lawyer and said, slowly and clearly, “I don't think I like your tone, sir.”

“Then I apologise,” Kenealy said, sounding not one whit apologetic. “I remind you, however, that I'm acting on behalf of Sir Roger Tichborne, in whose house you currently stand.”

Henry Hawkins interrupted: “That remains to be seen, Kenealy. And for your information, Sir Richard and Mr. Swinburne are here as guests of Colonel Lushington and at the behest of the Doughty and Arundell families, who have a stake in this property and whose identities are beyond question.”

“Do you mean to imply that my client's identity is in question?” Kenealy growled.

“I absolutely do,” Hawkins answered. “And I intend to have him prosecuted. It is blatantly obvious that this individual is an imposter!”

Doctor Jankyn stepped forward, shaking his head. “No, Mr. Hawkins,” he said. “You're wrong. This is Sir Roger. I couldn't mistake him. I knew him for the first two decades of his life.”

Hawkins rounded on the physician. “I don't know what you're playing at, sir, but if I find that you're a willing participant in this conspiracy, I'll see you behind bars!”

“The doctor and the butler have both acknowledged my client's identity,” Kenealy snapped, “as has Colonel Lushington-”