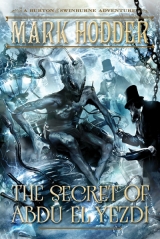

Текст книги "The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанры:

Детективная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Lawless shook his head. “Thank you, but we must pass up the invitation, Sir Roderick. I have to summon the police to fetch Mr. Oliphant, and there is much to do aboard ship. We’ll be flying up to the RNA Service Station in Yorkshire next week for a refit and will begin preparations immediately.” He turned to the others. “Captain Burton, Sister Raghavendra, your luggage will be delivered to your homes within the next couple of days.”

Murchison said, “Very well. I shall see you on Monday, then. Medals, Captain! Medals! And well earned!”

Burton and Raghavendra said their farewells to Lawless then Murchison hustled them down the ramp, across the landing field, and into a waiting steam-horse-drawn growler.

“Back the way we came, please, driver!” Murchison called up to the massively built individual on the box seat.

“All the way to the Royal Geological Society, sir?”

“Geographical. Yes, all the way there. Fifteen Whitehall Place.”

“Right you are. Geographical, as what I said. Hall aboard? Hoff we bloomin’ well go! Gee-up!”

As the conveyance lurched into motion, Murchison said to Burton and Raghavendra, “Incidentally, I have good news. Last month, the RGS was officially sanctioned. The king, in recognition of your discovery, issued us with a royal charter. We are establishment now.”

Burton put his hand up to his beard and slowly dragged his fingers through it. “A royal charter, you say? You didn’t attempt to inform us of that by telegraph last night, did you?”

“No. Why would I when it was just a matter of hours before your arrival? Besides, as I mentioned, the whole telegraph system has been crippled since midnight.”

Burton grunted. “Hmm! Peculiar. Our own telegraph went off the rails and churned out a lot of gibberish. There were a few English words mixed in with it—‘royal charter’ being two of them. Quite a coincidence.”

“Stroyan,” Murchison said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Stroyan. He was trying to get through from the Other Side. They say all past and future knowledge is available in the Afterlife. William obviously saw that the king has endorsed our organisation and, through means of the dysfunctional telegraph, tried to tell you.”

“If I may,” Sister Raghavendra interrupted, “I don’t wish to diminish the significance of the royal charter, Sir Roderick, but surely where matters of life, death, and the Afterlife are concerned, it’s a comparatively trivial matter? Surely, if William’s spirit were to contact us, it would have something more substantial to communicate?”

Murchison crossed his arms. “It was merely conjecture. Should I assume, then, Sister, that you’ve adopted Captain Burton’s skepticism where the Afterlife is concerned?”

“I remain open-minded.”

Murchison acknowledged her statement with a hum then addressed Burton. “But you’ve returned from Africa with your objections intact, I suppose?”

“As before, I neither support nor denounce the idea,” Burton replied. “Whether there is an Afterlife or not, I simply do not know, and since I exist in the material world, nor do I need to know. What I oppose is the undue influence in our society of spiritualists who claim to convey messages to us from the departed. In the event that the mediums aren’t all charlatans and the communiques are real, I have to ask, what motivates the dead to make the effort? Why are their messages so frequently abstruse? What is their agenda? No, Sir Roderick, I’ll not have it. My life is my own and Death will come in due course, but until it does, I’ll avoid the Afterlife, will make my own decisions, and will brook no meddling from Beyond.”

The three of them grabbed at hand straps to steady themselves as the growler navigated a corner.

“As a non-believer, you are in the minority,” Murchison observed.

“Quite so. The majority succumb to blind hope and allow it to compromise their intellect.”

“You have no hope?”

“I am realistic. My mind dwells on the lessons of the past and the challenges of the present, not on the unknowable future.”

“Ah ha! So you dismiss prognosticators as well as mediums?”

“Of course. They are obviously fraudsters.”

Sister Raghavendra patted Burton’s arm and said to Murchison, “In expressing his views, Captain Burton is never backward in coming forward. We had many discussions of a philosophical nature during our safari. After each one, I felt as if I’d been savaged by a jungle cat.”

“I fear for Miss Arundell,” Murchison mused. “Has she any lion-taming skills, Burton?”

The explorer gave a slight smile. “Isabel believes she’ll eventually beat me into submission with her ferocious Catholicism.”

Murchison shook his head despairingly. “Of all the people to marry into the country’s most influential Catholic family, I’d never have predicted it to be you. How do her parents feel about welcoming a stubborn and outspoken atheist into their clan?”

“When she told them, her mother became hysterical and fainted and her father vowed to shoot me. She’s had a year to work on them. Perhaps they’ve calmed down.” Burton coughed and moved his tongue around in his mouth. “Really, can this awful stink possibly get any worse?” He fished a handkerchief from his pocket and pressed it to his nose.

“We’re next to the Thames,” Murchison said. “This time last year, the stench was so bad they had to abandon parliament. Thank heavens for Bazalgette!”

“Who is he?”

“Joseph Bazalgette—a freshly emerged luminary among the DOGS. His designs for an advanced sewer system were approved a few weeks after your departure and he got to work immediately. The city has been in upheaval, but there’s not a single citizen who isn’t happy to put up with the nuisance of it in the knowledge that, when the tunnels are completed, the air will be breathable and the roads clean. Actually, Burton, you timed your expedition well.”

“How so?”

“There’s a subterranean river—the Tyburn—that flows through your part of town, under Baker Street, Marylebone, and Mayfair, beneath Buckingham Palace, on through Pimlico, and into the Thames slightly to the west of Vauxhall Bridge. Bazalgette has incorporated it into his system. It was one of the first parts to be constructed, so for many weeks the district where you live was badly disrupted. You avoided much inconvenience.”

“It’s finished now?”

“That part of it, yes. The Tyburn now runs into one of the system’s main arteries—the Northern Low-Level Sewer—which, when complete, will extend all the way from Hackney in the west to Beckton in the east, running parallel to the northern shore of the Thames. By God! You should see it, Burton! Such an undertaking! It’s the Strand that’s suffering at the moment—and its theatres and hotels are vociferous in their complaints, as you’d expect—but Bazalgette works like a demon. It won’t be long before that part of the city returns to normal while he ploughs onward into the Cauldron.”

“Gracious!” Raghavendra exclaimed. “He’s going into the East End? Isn’t that awfully dangerous?”

Her concern was justified. London’s East End was the city’s poorest, meanest, and filthiest district. A labyrinth of narrow alleyways, bordered by decrepit and overcrowded tenements, overflowing with raw sewage and rubbish of every description, it bred disease and despair in equal measure. The destitute lived amid the squalor in vast numbers and were vicious to such a degree that the police wouldn’t go near them. Disraeli had famously referred to the area as “a country within our country, and a damned wicked one at that.” When asked how to best solve the problem, he’d replied, “With fire.”

Murchison nodded. “Of course, but even criminals and ne’er-do-wells can see the advantage of having their effluence flushed away. The gangs that operate there have guaranteed that Bazalgette’s people will be protected and treated well.”

“Will wonders never cease?” Burton murmured. His eyes started to water. He took slow and shallow breaths.

Murchison smiled. “You’ll adjust, old boy. You’ll need to. To a lesser degree, this stench currently pervades all of London north of the Thames.”

“Why so?”

“Because until the principal west-to-east artery is finished, all the smaller tunnels running into it, flowing from north to south—the Tyburn included—have had their flow tightly restricted by a sequence of sluice gates. The muck is backing up, and it may well rise into the streets before it can be released into the completed system.”

“And south of the river?” Raghavendra asked.

“Tunnels are still being constructed to carry the effluence into the Thames. When they’re done, another big west-to-east intercepting tunnel will be constructed, parallel to the river’s south bank.”

“Incredible,” Burton said. “A monumental task!”

“Quite so. Bazalgette is a miracle worker.”

Sister Raghavendra, who appeared less affected by the stink, asked, “And what other progress has been made by the Department of Guided Science, Sir Roderick? Its inventors are so prolific, I fully expect London to be unrecognisable to me once this fog clears.”

“Steam spheres,” the geographer answered.

“And what are they?”

“Horseless carriages—large ball-shaped machines with a moving track running vertically from front to back across the circumference, giving motive power. They are two-man vehicles. Not much good for the city streets—which are too crowded—but excellent for a run in the country.”

The growler swayed and bumped. They heard the driver shout something insulting, probably to someone who’d blocked their path.

“And submarine boats,” Murchison continued.

“Vessels that travel beneath the surface of the sea?” Raghavendra guessed.

“Exactly so.”

“My goodness. Whatever for?”

“The DOGS have but a single bark, my dear: Because they can!”

Burton pushed aside the curtain and peered out of the window. Vaguely, he saw gasworks looming out of the fog, and deduced that the growler had by now traversed the complete length of Nine Elms and was proceeding north through Lambeth.

“Not much traffic,” he observed.

“You haven’t noticed,” Murchison said, “no doubt because you’re acclimatised to Africa, but it’s very warm for the time of year. We’ve had the hottest summer in living memory and it’s brought with it regular London particulars. In such murk, people fear to set foot in the streets lest they get lost or mugged.”

“Or suffocate.”

“Indeed.”

“Our driver appears to know where he’s going.”

“He’s a reliable cove. Montague Penniforth. I use him a lot. He normally drives a hansom but hires a growler when he has occasion to. I’m convinced he can see in the dark.”

Burton let the curtain fall back into place. He wiped his eyes with his handkerchief then pressed it again to his nose. He’d spent most of the day sleeping aboard the Orpheus, but although he felt much recovered, his hands were still trembling and his throat was dry. Dropping his left hand to his pocket, he surreptitiously felt the outline of a bottle of Saltzmann’s Tincture.

During the course of the next half-hour, Murchison and his companions discussed various incidents that had occurred during the expedition, while the growler took them along Palace Road to Westminster Bridge, crossed the reeking Thames, turned right at the Houses of Parliament, and trundled along King Street and Whitehall to Whitehall Place. Finally, it drew to a stop outside number 15, a many-windowed building situated opposite Scotland Yard.

The passengers disembarked. Murchison paid Penniforth and the carriage departed, its wheels grinding over the cobbles, its engine panting smoke.

“Two or three hours, my friends,” Murchison said. “That’s all we ask of you. Just time enough to take a drink with your fellows and entertain them with a few tales of derring-do. Then you’ll have three days to recuperate before the ceremonies at the palace.”

Burton looked at the building’s grand entrance.

Knighted! He was going to be knighted!

It would give him influence.

Damascus. Marriage. Books. No more of this. No more RGS. No more exploring. No more danger.

Tomorrow, he’d get back to his half-finished translation of the Baital-Pachisi, a Hindu tale of a vampire that inhabits and animates dead bodies. With that completed, he’d be able to commence his great project, a fully annotated version of A Thousand Nights and a Night, translated from the original Arabic—an undertaking which, he reckoned, would keep him busy for at least the first couple of years of his consular service.

“Shall we?” Murchison asked, waving Burton and Raghavendra toward the door.

They crossed to it, pushed it open, and entered.

“There has always been a world beneath London.

There is more below than there is above.”

–JOSEPH BAZALGETTE

By nine o’clock, Sister Raghavendra had already made her excuses and left the RGS, and Burton was eager to do the same. Fighting off the many protests, he extracted himself from the reception party, collected his hat, jacket, and cane from the lobby, and stepped out into Whitehall Place. To his surprise, the fog had been completely swept away by a warm night breeze and the air was clear. Even more amazing, though it was night, he emerged into what appeared to be broad daylight. He looked up and his jaw dropped. For a second night, the aurora borealis was rippling overhead.

A large number of detectives, clerks, and secretaries had forsaken their offices in the Scotland Yard building and were standing in the street gazing at the spectacular illumination. One of them, a gaunt chap with thick spectacles, a red nose, and a straggly moustache, moved to Burton’s side and said, “Quite a sight, isn’t it? Have you ever seen the like?”

“I haven’t,” Burton confessed. He was tired, wanted to get home, and felt a little bit drunk. He’d also downed the remaining half of the Saltzmann’s Tincture and needed to walk off its effects.

You’re driving yourself to collapse. Why do you never know when to call it quits?

“Aren’t you the explorer chappie?” the man asked. “Livingstone?”

“Burton.”

“Oh, yes! That’s right. The Nile man. Congratulations! Pepperwick. That’s me. Clerk. Scotland Yard. Ordinary sort of job. Not romantic, like yours.”

Burton ran a finger around his collar, feeling the grit that had already accumulated there.

Welcome home.

“The world over, apparently,” Pepperwick went on, using a thumb to gesture upward. “The lights, I mean. Fancy that! At this precise moment, right now, there’s no night anywhere. Do you think it’ll last?”

“I don’t know what to think.”

Burton examined the crowd, his eyes roving from person to person. He noticed that one man, a thickset individual, was gazing not at the aurora borealis but at him. Burton stared back. The man’s eyes widened. He looked shocked. Then he turned and hurriedly moved away.

“I should get home, Mr. Pepperwick.”

“You’ll not have any trouble finding your way. It’s all topsy-turvy. The days are darkened by fog, the nights are lit up by whatever-it-is.”

“Indeed,” Burton agreed. “Good evening to you.” He touched the brim of his topper, strode off, and at the end of the street turned right into Charing Cross Road, heading toward Trafalgar Square.

For the first time since his return, Burton plunged into one of London’s throbbing arteries and was engulfed by the cacophony of the world’s most advanced city.

The middle of the thoroughfare was clogged with traffic. Horse-drawn wagons, carriages, and omnibuses vied with their steam-powered counterparts, the animals snorting and shying away from the hissing, growling, spluttering, iron-built competition. ‘Penny-farthing’ velocipedes clattered and bounced between the larger vehicles, their riders shouting and cursing through clacking teeth.

Burton espied one of the new steam spheres, which, he thought, was probably being condemned as a wasted expense by its owner due to it being jammed between—and completely immobilised by—a coal cart in front, a hearse to its left, a landau carriage on its right, and a massive pantechnicon behind. Amid the general hubbub, he could hear the sphere’s driver yelling, “Get out of my way, confound you! Get out of my blessed way!”

The sides of the road were lined with stalls and braziers offering jellied eels, pickled whelks, sheep’s trotters, penny pies, plum duff, meat puddings, baked potatoes, Chelsea buns, milk, tea, coffee, ale, mulled wine, second-hand clothes, old books, flowers, household goods, shoes, kitchenware, tools, and practically everything else a person could possibly eat, drink, or require for the home; as well as astrological charts, palm and tarot card readings, scrying by tea leaves, and prognostication by numbers, by bumps on the head, by marks on the tongue, and by the throw of a dice. The sing-song tones with which the traders called attention to their wares were almost, to Burton, the master linguist, an entirely unique dialect, barely comprehensible but very, very loud.

Between the stalls and the shops that bordered the street—many of which were currently open beyond their normal business hours—the pavements were packed with pedestrians who thought to take advantage of the peculiar light and the mild weather. There were couples and bachelors out strolling, ragamuffins playing and yelling and begging, dolly-mops touting for customers, jugglers juggling, singers warbling, musicians scraping and plucking, vagrants pleading and wheedling, and thieves as numerous and as persistent as African mosquitoes.

Burton shouldered through them, slapped away the pernicious fingers of pickpockets, and made painfully slow progress into Trafalgar Square and up St. Martin’s Lane, where he hoped to find Brundleweed’s jewellery shop open. Shortly before leaving for Africa, he’d ordered a diamond ring from old Brundleweed. The man was a craftsman of exceptional ability, and the explorer was looking forward to seeing the item in which he’d invested a considerable sum.

It was not to be. The shop was closed.

He strolled on into Cranbourn Street, followed it to Regent Circus, and traversed Regent Street up to the junction with Oxford Street.

Here, as fatigue gripped him and he realised he’d overestimated his strength, he made the decision to leave the main roads and cut diagonally through the Marylebone district to the top of Baker Street. It was more dangerous—he would have to pass through a poverty-stricken enclave of alleyways and crumbling tenements—but it would be quicker.

Keeping a firm hold of his swordstick, he entered a long side street. Shadows shifted around him as the aurora folded and glimmered overhead. A strange clicking began to echo from the walls to either side. He stopped and looked up. The clicking became a chopping. The chopping became a roar. A rotorchair skimmed over the rooftops and was gone, its noise rapidly receding, its trail of steam hanging motionless in the air, changing colour as it reflected the uncanny light.

Burton pushed on. He turned left. Right. Right again. Left. The maze of alleys narrowed around him. The stink of sewage haunted his nostrils. Mournful windows gaped from the sides of squalid houses. An inarticulate shout came from one of them. He heard a slap, a scream, a woman sobbing.

A man lurched from a dark doorway and blocked his path. He was coarse-featured, clad in canvas trousers and shirt with a brown waistcoat and a cloth cap. There were fire marks—red welts—on his face and thick forearms.

A stoker. Spends his days shovelling coal into a furnace.

Run. He’s dangerous.

I’m dangerous, too.

“Can I ’elp you, mate?” the man asked in a gravelly voice. “Maybe relieve you of wha’ever loose change is weighin’ down yer pockits?”

Burton looked at him.

The man backed away so suddenly that his heels struck the doorstep behind him and he sat down heavily.

“Sorry, fella,” he mumbled. “Mistook you fer somebody else, I did.”

The explorer snorted scornfully and moved on. His friend, Richard Monckton Milnes, had once told him he had the face of a demon. Sometimes, it was useful.

Burton continued through the labyrinth. A sense of déjà vu troubled him. Was it because the depths of London felt remarkably similar to the depths of Africa—tangled, perilous, toxic?

He came to a junction, turned left, and stumbled over a discarded crate. An exposed nail gouged into his trouser leg and ripped it. Burton spat an oath and kicked the crate away. A rat leaped from it and scuttled into a shadow.

Leaning against a lamppost, the explorer rubbed his eyes. Last night he’d been in the grip of a fever after a month-long illness and now he was walking home. Dolt!

He noticed a flier pasted to the post:

The Department of Guided Science.

A Force for Change. A Force for Good.

Developing the British Empire.

Bringing Civilisation to All.

“Whether you want it or not,” he added.

Pushing himself away, he continued along the alley and turned yet another corner—he wasn’t sure exactly where he was but he knew he was heading in the right general direction—and found himself at the end of a long, straight street bordered by high and featureless red-brick walls: the sides of warehouses. The far end opened onto what looked to be a main thoroughfare—Weymouth Street, he guessed. He could see the front of a shop, a butcher’s, but before he could read its sign, steam from a passing velocipede obscured the letters.

Burton walked on, carefully stepping over pools and rivulets of urine and filth.

A litter-crab came clanking into view near the shop, its eight thick mechanical legs thudding against the road surface, the twenty-four thin arms on its belly darting this way and that, skittering back and forth over the cobbles, snatching up rubbish and throwing it through the machine’s maw into the furnace within.

The machine creaked and rattled past the end of the alley and, as it did so, its siren wailed a warning. A few seconds later, it let out a deafening hiss as it ejected hot cleansing steam from the two downward-pointing funnels at its rear.

The automated cleaner vanished from sight as a tumultuous wall of white vapour boiled toward Burton. He stopped and took a few steps backward, leaned on his cane, and waited patiently for the cloud to disperse. It billowed toward him, extending hot coils which slowed and became still, hanging in the air as they cooled.

Movement.

Someone was entering the alley.

Burton watched as the person’s weirdly elongated shadow angled through the mist, writ dark, skeletal, and horrific by the distortion.

He suddenly felt uneasy and waited nervously for the shadow to shrink, to be sucked into the person to whom it belonged when he—for surely it must be a man—emerged from the cloud.

It did shrink.

It was a man.

He was aiming a pistol at the explorer.

“Captain Richard Francis bloody Burton,” the individual snarled. “Drop your stick or I’ll shoot you in the arm.”

Burton dropped the stick.

“Get back against the wall. Take your hat off, put it down, and stand with your hands on your head.”

Burton did as ordered, watching the man through narrowed eyes. He recognised him. It was the individual who’d been staring at him outside Scotland Yard—a short, big-boned, and heavily muscled fellow with wide shoulders and a deep chest. He had thick fingers, a blunt nose, and, under a large outward-sweeping brown moustache, an aggressively square chin.

“I’ve been waiting to meet you,” the man said, in a slightly husky voice. His pistol didn’t waver. It was aimed steadily at a point between the explorer’s eyes. “The moment I saw your likeness in the newspaper, I knew I’d seen you before.”

“Who are you?” Burton demanded. “What do you want?”

“My name is—is Macallister Fogg. How old are you?”

“How old? Rather an impertinent question. Thirty-eight. Why?”

“Mind your own business. Where were you on the tenth of June, 1840?”

Burton frowned, puzzled. “The Assassination? I was on a ship from Italy bound for Dover, on my way to enroll at Oxford University.”

The other man muttered to himself, “Plausible. But I could swear to it! I could swear!”

“If there’s something I can—?”

“Be quiet. Let me think for a moment.”

Burton sighed in exasperation and threw out his arms. “What in blue blazes is this about, Mr. Fogg? Do you intend to rob me?”

“Stop moving! Hands on head!”

The explorer shrugged, put his right foot against the wall, and launched himself forward. He chopped his hand down onto the other’s wrist, knocking the pistol out of his grasp. As the gun went spinning over the cobbles, Burton sent an uppercut crashing into the man’s chin. Fogg’s head snapped back and he stumbled, emitting a loud grunt before steadying himself.

His pale blue eyes met Burton’s. “So, it’s to be like that, is it?”

Burton was astonished. He’d boxed at university and in fight pits in India and had never been beaten. The uppercut had been his best shot. It should have knocked the man cold. Was his strength really so diminished?

“I’ll not submit to a mugging,” he growled, and took up the fighter’s stance.

Fogg grinned, as if relishing the prospect of battle, and mirrored the explorer’s posture. “I have no interest in your valuables,” he said, and suddenly ducked in and sent a fist thudding into Burton’s ribs. The explorer doubled over. Lights exploded in his head as knuckles smashed into the side of it, then into his mouth, then into his right eye. He fell, rolled, and jumped to his feet, stumbling back, suddenly feeling completely sober, horribly weak, and utterly befuddled.

Fogg had recovered his pistol. Burton looked down its barrel and raised his hands.

“Will you please explain?” he slurred. “Has it something to do with Prince Albert?”

“Albert? Why would it concern him?”

“I was with him this morning.”

“So?”

“So he was Victoria’s husband. He was present when she was shot.”

“It has nothing to do with Albert,” Fogg said. “Your father—do you resemble him at all?”

“What? My father? Not in the slightest bit.”

“By Jove! It has to be you! Except you’re simply too young. It’s impossible.” Fogg scowled, looked at his gun, hesitated, and lowered it. “Confound it! I suppose I should apologise. A case of mistaken identity, Burton, that’s all.”

“That’s all? I’d appreciate a rather more enlightening excuse, if you don’t mind,” Burton said, relaxing his arms.

“I do mind. You’ll not get one.”

“Then your address, please, Mr. Fogg, for the laundry bill.” Burton indicated his dust-stained overcoat and trousers.

Fogg raised his pistol again. “Enough. Get going.”

Burton gritted his teeth, picked up his hat and cane, and slowly walked to the end of the alley.

Just as he was about to turn the corner, his assailant shouted after him, “Hey!”

Burton looked back.

“If it’s any consolation,” Fogg called, “my head is still spinning from that uppercut of yours.”

The explorer’s eyes locked with the other man’s for a moment, then he turned and strode away.

By the time he reached number 14 Montagu Place, Burton was light-headed, shaking, and perspiration beaded his brow. He opened the door, entered the hallway, and saw Mrs. Iris Angell frozen in mid-step halfway along the passage. His landlady, a white-haired, broad-hipped, sprightly old dame—who also functioned as his housekeeper—was gaping at him as if he were a ghost.

He removed his topper and put it on the hat-rack, placed the cane in an elephant-foot holder, and popped open his collar button.

Mrs. Angell let loose a shriek and threw her not inconsiderable weight across the intervening space and into his arms.

“My goodness! My goodness! What has Africa done to you? You’re as thin as a broom handle! Your lip is bleeding! Your eye is black! Your trousers are torn! You look as sick as a dog! Isabel has been waiting! We knew you’d be arriving today but thought you’d be home earlier! You found the Nile, Captain Burton? Of course you did! The papers say you’re a hero! Are you hungry? What do you think of the light in the sky? Do you know what it is? I’ll get you fresh clothes! My goodness!” She raised her voice to a shrill scream. “Miss Isabel! Miss Isabel!”

Burton disentangled himself from her arms. “Slow down, Mother Angell. Calm yourself. I’m quite fine. I’ve been a little ill and I had a slight accident on the way here, but it’s nothing to be concerned about. The comforts of home will soon put me to rights.”

“Oh!” she cried out. “Thank the Lord you’ve returned to us. Such a long time away and every single day of it I worried you were being eaten by giraffes or stung by poisonous monkeys.”

“Africa wasn’t so bad,” he responded. “I’ve already encountered more danger right here in London. And to answer your earlier questions—no, I’m not hungry, and yes, fresh clothes would be most welcome. Isabel?”

A mellow voice sounded from the top of the stairs. “Dick.”

He looked up and saw Isabel Arundell, having obviously just emerged from his study, standing on the landing. She was tall, slender, and pretty—with large clear eyes, a straight Grecian nose, and thick, lustrous blonde hair.

“A pot of tea, please, Mrs. Angell!” he bellowed, and shot up the staircase and into Isabel’s embrace.

She held him tightly and sobbed onto his shoulder.

“Isabel,” he whispered. “Isabel. Isabel.”

He pushed her away a little, so he could lean in and kiss the side of her neck. His split lip left two small spots of blood on her jugular.

“Blanche is here!” she gasped.

“I don’t care,” he said. “I have to kiss you. You waited.”

“Of course I did. You’re bleeding. You look all banged-up. Have you had an accident?”

“Yes, just a mishap.” He pulled out his handkerchief, wiped the little red stains from her skin, and dabbed the square of cotton against his mouth.

“We can marry,” he said. “I’m done with Africa.”

“Come and say hello to her.”

“Isabel, have your parents given their blessing?”

“Not their blessing, but their permission. They realise I won’t accept any other man.”

He nodded, checked his handkerchief, put it away, and followed her into the study.

It felt strange to be back. Nothing had changed, but it all appeared dreamlike in the shifting multicoloured illumination that streamed in between the open curtains. His three desks were still piled high with books and papers; the swords and daggers still hung on the wall over the fireplace, with spears and guns in the alcoves to either side; his old boxing gloves still dangled from the corner of the mantelpiece; the bureau still stood between the two tall sash widows; the bookcases were still warped beneath the weight of his books; and his comfortable old saddlebag armchair was right where he’d left it.