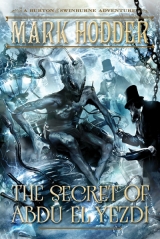

Текст книги "The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанры:

Детективная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“. . . I’m hit! Mother of God! I’m . . .”

“. . . and what is left worth fighting for? Surrender, I say. It’s the . . .”

“. . . can’t trust him to . . .”

“. . . Get down! Get down! He’s dead, damn it! Sweet Jesus, they aren’t human! We have to . . .”

And more. These odd, panicked, desperate echoes became, unmistakably, the yammering of men caught in warfare and making a last stand against superior forces. I’m not certain how, but I was taken by the notion that their one hope had betrayed and abandoned them, and that whoever or whatever that last hope had been, it was here, now, on the island, and was the awful presence we’d all sensed.

We were but a few steps from the globe when the illumination suddenly increased until it blazed like the sun. The next thing I knew, I was on the ground and Rodgers was shaking the wits back into me. I sat up, looked around, and saw only rocks and pools and the sloping sides of the crater. The mirage was gone.

“Let’s get out of this accursed hellhole,” John Judge said. “I beg of ye, Cap’n Taylor, let us get back to our people.”

I’d no hesitation in agreeing, and we climbed out of the crater as fast as was possible and immediately started down the path toward Santa Cecilia. Minutes later, the rain fell, and we were sent slithering wildly down the track amid mud and water. Lord knows how we survived that slide.

Night fell before we’d completed the descent but we hastened on by starlight, convinced that we were being pursued, though by what we couldn’t guess. Never have I felt such stark terror!

Sunday. 9th day of October 1859

3.00 p.m.

We didn’t realise it at the time, but there were no drums last night. We reached the village at dawn and, being fatigued beyond endurance, immediately took to our huts and, at last, slept.

Midnight

Again, no drums. Why does this cause me such dread?

Monday. 10th day of October 1859.

9.00 a.m.

A cannon heard from the Royal Charter! It can mean only one thing! Let everything that has breath praise the Lord! Praise the Lord! For He, in His infinite mercy, has given us fire! We can flee this detestable place!

Noon

The crew and passengers trekked from Santa Cecilia to Santa Isabel and from there boarded the ship. We had to carry John Judge. He is in such a deep sleep that he won’t wake.

We’ll be away from here!

“My hat!” Swinburne exclaimed. He untangled his legs, stood, and moved to the bar. “They spent more than a month on that island. Wasn’t the ship reported missing?”

“They were sailing from Melbourne,” Burton said. “With a voyage of that length, a month’s delay isn’t so unusual.”

Swinburne claimed fresh bottles of ale and brought them back to the table.

“What on earth was it?” he asked. “The globe of light? The aurora? It’s astonishing!”

“Born from the wreck of the SS Britannia,” Burton murmured.

Swinburne regarded him curiously. “What? What? What?”

“I’ll explain later. Here, I’ll pour the drinks, you continue with the log.”

The poet’s green eyes fixed on Burton for a few seconds then he gave a grunt, looked down at the book, and resumed.

Monday. 10th day of October 1859.

7.00 p.m.

I will bless the Lord at all times; His praise shall continually be in my mouth. Fernando Po is receding behind us! Admittedly, the going is slow. The steam engine was designed to augment the sails, not replace them, but at least it drives us from hell and gives us hope.

Tuesday. 11th day of October 1859.

3.00 p.m.

Crawling along. Currently at 1°34′N, 3°23′E.

Wednesday. 12th day of October 1859.

9.00 a.m.

Passenger Colin McPhiel found dead this morning. No ascertainable cause. Have ordered corpse preserved in lime for Christian burial in God’s good earth. Crew and passengers now convinced the ship is blighted. I argue against superstition, but in the name of the Almighty, I feel it myself.

3.00 p.m.

The lassitude that immobilised us on the island is still with us. Many men, women, and children affected, in various degrees, some practically comatose.

Thursday. 13th day of October 1859.

9.00 a.m.

Seaman Henry Evans and Second Steward Thomas Cormick both died in the night. Again, no reason apparent. Placed in lime.

Noon

2°38′N, 13°8′E.

9.00 p.m.

Passenger Benjamin Eckert has committed suicide by hanging. Used the last of the lime to preserve his corpse. What doom weighs so heavily upon this vessel?

Friday. 14th day of October 1859.

7.00 a.m.

Joseph Rodgers mad with terror. Insists he saw passenger Colin McPhiel walking the deck in the early hours of this morning. I have sent him (Rodgers), Seaman William McArthur, and Quartermaster Thomas Griffith to the hold to check on the corpse.

7.30 a.m.

They report the body is present but has been disturbed; lime scattered around the casket.

8.00 p.m.

Have put Seamen Edward Wilson, William Buxton, and Mark Mayhew on a rotating watch over the hold.

At 8°55′N, 20°39′E. Making for Cape Verde to resupply.

Saturday. 15th day of October 1859.

3.30 a.m.

Shaken from my bed at 2.30 a.m. by Cowie and Rodgers. Utter chaos in the hold. Buxton and Mayhew both dead. No marks on them, but by God, the look of horror on their faces! Edward Wilson a gibbering lunatic. Struck out wildly at all who approached him. Had to call upon John Judge to restrain the man. Corpse of Colin McPhiel stretched out on the deck, powdered with lime, a dagger embedded hilt-deep in its heart.

I’m at a loss. I’ve ordered the bodies of Buxton, Mayhew, McPhiel, Evans, Cormick, and Eckert cast overboard. Wilson bound and locked in cabin.

Noon

Finally, the wind has got up, but our evil luck continues, for it’s driving us westward. Currently at 9°24′N, 24°18′W.

11.00 p.m.

11°21′N, 28°57′W. We’ll not make Cape Verde this day.

Sunday. 16th day of October 1859.

10.00 a.m.

Passengers Mrs. C. Hodge, George Gunn, Franklin Donoughue, and Seaman Terrance O’Farrell, all dead. No indications of disease other than the severe lethargy from which they’d all suffered. By Christ, am I commanding a plague ship? Bodies thrown overboard. No energy or will for ceremony.

1.00 p.m.

Joseph Rodgers bearded me in my cabin and ranted for half an hour. He said: “Satan is sucking the souls right out of us, Captain Taylor. We’ll all be dead afore this ship touches another shore.”

Monday. 17th day of October 1859.

7.00 a.m.

Ten taken. Passengers: Mrs. J. B. Russell, Miss D. Glazer, P. N. Robinson, T. T. Bowden, T. Willmoth, and A. Mullard. Crewmen: Second Officer A. Cowie, Rigger G. A. Turner, Fourth Officer J. Croome, Seaman W. Draper.

3.00 p.m.

A strong southerly wind has driven us to 19°28′N, 30°14′W.

5.00 p.m.

There was a medium among our passengers, known to all as Mademoiselle Tabitha, though the manifest lists her as Miss Doris Jones. I didn’t see her on the island. Apparently she spent our days there curled up in a corner of a hut and spoke to no one. Since we departed, a similar story: locked in her cabin, opening the door only to receive food from a friend among her fellow passengers. An hour ago, I was told she wanted to see me. Went down and found her seemingly in a trance.

She said, “He is reaching out, Captain. Speaking through the mouth of a woman like me.”

I asked, “Who is?”

She said, “Our additional passenger. He who hides. He who feeds. He who endures to the end.”

I asked, “We have a stowaway?”

To this, she giggled like a madwoman and said, in an oddly deep voice, “Let us say au revoir before I embarrass myself any further. I have the royal charter. I’m on my way. We shall meet soon. Say goodbye to the countess.”

She reached out as if grasping something in the air and made a twisting motion, before then clutching at her chest and collapsing to the floor, stone dead. I have no explanation.

8.30 p.m.

I have had the ship searched from bow to stern. No stowaway detected.

Tuesday. 18th day of October 1859.

5.00 a.m.

Twelve more gone. I shan’t list them here but will add the date of their demise against their names on the passenger and crew manifests.

Rodgers informed me that he witnessed John Judge “creeping” around the ship during the night. I approached Judge half an hour ago. He explained that he’s started to keep a nightly watch. The man is not crew, but his intimidating size is such that I am glad of his vigil.

Noon

Developing storm. We are driven NNW.

Saturday. 22nd day of October 1859.

Time unknown. Daylight.

Impossible to maintain this log. Mass panic aboard. Fighting. Suicides. The death toll increases every night. Seaman Gregory Parsons attempted to lead a mutiny. Joseph Rodgers forced to shoot him dead.

We are in the stranglehold of an increasingly violent maelstrom. Compass spinning. Timepieces have stopped. Sky black with cloud. Unable to establish position.

Monday. 24th day of October 1859.

Time unknown.

Storm so intense I don’t know if it’s night or day.

Death. Nothing but death. Passengers refusing to leave their cabins.

Time unknown.

Rodgers has become convinced that John Judge is responsible for the evils that beset this vessel. He’s going after him with a pistol. I am powerless.

Time unknown.

Not enough crew remaining to man the ship. I have to get it to port. I have to—else we’re all dead.

Note.

This writ by Joseph Rodgers at Capt. Taylor’s command.

The Capt. pegs us as in the Irish Sea. He is bound to the wheel so as not to be washed overboard and is set on steering us to any port we can find. I am to wrap this logbook in sealskin and return it to him, so it might be on him if we are wrecked.

Beware of John Judge. Satan took him on the island and he has preyed on us this voyage through. He walks by night and steals a man’s soul from him and leaves the body dead but not dead. I saw Colin McPhiel rise and hunt for souls to replace what was took from him.

The Royal Charter is damned. Capt. Taylor is damned. I am damned. We are all damned. But I’ll not go without a fight. I have me pistol loaded and as God is me witness I’ll search this ship from bow to stern till I find Judge and send him back to hell with a bullet.

Lord have Mercy on my soul.

“As for a future life, every man must judge for himself between conflicting vague probabilities.”

–CHARLES DARWIN

“That’s the end of it,” Swinburne said. “Phew! What terror! I shall have nightmares!”

Trounce exclaimed, “I’d lay good money on it being Joseph Rodgers who made it ashore and John Judge who followed and killed him.”

“La Bête est venue,” Eliphas Levi whispered.

“The Beast has come?” Swinburne repeated. “What do you mean by that?”

Burton, Trounce, and Levi glanced at each other.

The poet banged his fist on the arm of his chair. “Out with it!” he commanded. “Explain what this is all about! You—” he jabbed his finger at Burton, “—are the man with a scar on his face. Abdu El Yezdi said my travails would begin when you appeared.” Swinburne lifted the logbook and waved it over his head. “If this Royal Charter tragedy and your interest in the Arabian are connected, then I demand to know how!”

Burton was silent for a few seconds then nodded. “Very well, but I must ask something of you first.”

“What?”

“I believe the Arabian mesmerised you, and I want to do the same. Maybe I can unearth whatever he caused you to forget.”

“You mean he removed something from my memory?”

“More likely he inserted something but made it inaccessible to your recollection. I’d like to know what.”

“And if I allow this, you’ll tell me the full story?”

“Yes.”

“Then do it. At once.”

Burton knew that under normal circumstances it would be impossible to put Swinburne into a trance. The poet had an excess of electric vitality. It caused him to be in constant twitchy motion and was at the root of his overexcitable personality. However, he was exhausted after his taxing swim and Burton had purposely asked him to read from the logbook to further tire him. Swinburne was drained—just as he must have been after ascending Culver Cliff—as was evinced by the relative idleness of his limbs.

Burton addressed Trounce and Levi. “Be absolutely still and quiet please, gentlemen.”

He drew his chair over so it faced the poet’s and leaned forward. “Algy, keep your eyes on mine. Relax. Mimic my breathing. Imagine your first breath goes into your right lung. Inhale slowly. Exhale slowly. The next breath goes into your left lung. Slowly in. Slowly out. The next into the middle of your chest. In. Out. Repeat that sequence.”

As Swinburne’s respiration adopted the Sufi rhythm, he became entirely motionless but for a slight rocking. Burton murmured further instructions, guiding the young man into a cycle of four breaths, each directed into a different part of the body.

The poet’s mind was gradually subdued by the developing complexity of the exercise. His pupils grew wider and his face slack. Burton, satisfied that he’d gained dominance, said, “Go back to Culver Cliff, Algernon. You have just made your climb and are lying on the downs at the top. A man named Abdu El Yezdi has met you there.”

“Yes,” Swinburne whispered. “The fat, snaggle-toothed old Arabian.”

“He’s spoken to you about courage and told you to look out for a man with a scar on his face.”

“Burton.”

“What did he do next?”

“He shifted closer to me and looked into my eyes. He was blind in one, but the other was like a deep well, and when he instructed me to breathe in a certain manner, I felt compelled to do so. I became very drowsy. He said, ‘Algy, I shall give you a verse. You will forget it until it is needed.’”

The poet raised his face toward the ceiling and recited:

Whene’er you doubt thy station in life

Thou shalt take to the tempestuous sea.

To all the four points it shall batter thee

Until you find thine own power, and me.

Swinburne looked at Burton and murmured, “What hideous doggerel.”

“Did he say anything else?”

“Just, ‘Thank you,’ then he told me to sleep. I don’t remember anything more until I awoke and he was gone.”

Burton said, “I shall count backwards from five. When I’m done, you’ll decide that explanations can wait until tomorrow. You’ll go straight up to bed and will enjoy a deep and restful sleep. Do you understand?”

Swinburne nodded.

“Five. Four. Three. Two. One.”

“My hat!” Swinburne exclaimed. “Are we to sit here all night? I can barely keep my eyes open.”

“It’s hardly surprising considering your earlier heroics,” Burton said. “You must be knocked out.”

“I am. I say—do you mind if I hit the sack?”

“Not at all. We’ll talk in the morning.”

The poet pushed himself to his feet, mumbled, “Nighty night, all,” and stumbled from the room.

Burton turned to face his companions. As he did so, Trounce emitted a loud snore. The detective was sitting with his head against the back of his chair, his eyes closed, and his mouth wide open.

“I think he pay too much attention,” Eliphas Levi observed.

“We are all exhausted, monsieur,” Burton noted. “Let’s get him to bed and each take to our own.”

“Oui, oui. But the verse, Sir Richard? Tell me, quelle est sa signification?”

“What does it mean? It appears to have caused Swinburne’s propensity for perilous swims but, beyond that, I really couldn’t say.”

Early the following morning, Bram Stoker set off in search of fellow Whisperers. Anglesey was a barren and sparsely populated island, but the lad assured “Macallister Fogg” that the web extended even to it, and if there was a working telegraph station in any of the towns, it would soon be located.

Meanwhile, the four men took a stroll along the edge of Dulas Bay. There was a stiff breeze blowing and clouds blanketed the sky, but the tempest was over. Villagers were clambering among the rocks below, calling to one another as they discovered yet more bodies.

“Ripples,” Burton murmured.

Trounce looked at the still-agitated sea and said, “Hardly.”

“No, old chap—I’m thinking about Time; wondering whether a disaster of this magnitude has touched other histories.”

Trounce, who hadn’t yet learned of Countess Sabina’s revelations, growled, “Whatever you just said, it’s beyond me, and if I listen to much more gobbledegook, I’ll have to dose myself with bitters and return to my bed. I think I’ll confine myself to the practical business of the here and now.”

Burton patted the policeman’s shoulder. “You’re a fine fellow, Trounce.”

Trounce gave a modest, “Humph!” but his chest swelled a little and he reached up and smoothed his moustache.

The king’s agent again surveyed the churning waters. “I was warned a storm was coming, but I considered the omen metaphorical. I never envisioned this.” He turned to Eliphas Levi. “Do you think there’s been a Royal Charter disaster in the original history, monsieur, or is it exclusive to ours, thanks to the presence of Perdurabo?”

“My hat!” Swinburne interrupted. “I do wish you’d explain to me what the devil you’re talking about!”

Burton said, “I shall do so now, Algy,” and indicated a large flat stone that overlooked the bay. The group settled on it, and the explorer went through the entire affair for the poet’s—and Trounce’s—benefit; he missed nothing out.

Swinburne accepted the wild story with complete equanimity.

“You understand what this means?” Burton asked. “That Time is not at all as we conceive it; that our history has been manipulated; that we appear to be caught between two warring factions—Abdu El Yezdi’s and Perdurabo’s?”

“As any poet of merit will tell you,” Swinburne replied, “at an individual level, reality is simply a function of the imagination; and at a collective, nothing but a suffocating mantle of compromise and acquiescence. That is why poets create unusual combinations of words and rhythms: to set all the possible truths free. What you have told me comes as no surprise.”

“You have une vision unique, Monsieur Swinburne,” Eliphas Levi observed. “It is one I think will prove most vital to Sir Richard.”

“How so?” Burton asked.

“Because, for Abdu El Yezdi and Perdurabo, you are history, monsieur—a figure from the past. Perdurabo, en particulier, he say he know you well. If he have study you, then he will be aware of what you will do, where you will be, how you will act.”

“Bismillah!” Burton cursed. “I hadn’t considered that. He’ll be ahead of me every step of the way.”

“Non! Non!” Levi protested. “Pas nécessairement. You forget—for Perdurabo, at least, this history is not his history. The Sir Richard Francis Burton he have knowledge of is not the same as you, for he is expose to different challenges and opportunities and maybe he make different decisions. Perhaps he never discover the source of the Nile. Perhaps he is not the agent of the king. But there may be many similarities, so you must be very careful. Il ne faut rien laisser au hasard, eh? It is clear that Perdurabo mean to harm you.”

Burton pulled a cheroot from his pocket. He looked down at it and saw that his hand was trembling. He suddenly sensed the Other Burton lurking. Had he now an explanation for it? Was he somehow able to discern—especially when in the grip of fever—his alternate selves?

“I understand the implication, Monsieur Levi,” he muttered. “You suggest that Algy’s distinctive view of the world is such that he’s perfectly placed to help me second-guess myself and do the opposite of whatever my instinct or intellect dictates, for perhaps only then will I take Perdurabo by surprise and gain the upper hand.”

“You speak as if going into battle,” Trounce observed.

“I feel I am. I wish I better understood what against.”

“You are correct,” Levi said. “And this one—” he tapped Swinburne’s shoulder, “—is like…how do you say it? Ah! Oui! The card up your sleeve, non?”

Burton regarded the little poet—who grinned happily back at him—and said, “Yes, I think you are right. And you’ve given me an idea.”

“Oui?”

Burton held out his arms.

Levi looked at them.

“La signification?”

“I have two sleeves. And, also, I have a brother.”

When they returned to The Spiteful Rosie, they found Bram waiting. He’d located a working telegraph office in Newborough, ten miles away.

“I’ll hire a vehicle and leave you gentlemen for a while,” Trounce said. “I must get a message to Slaughter and have him take charge of the hunt for John Judge. An island is no refuge for a murderer, so I’ve no doubt that he’s crossed the bridge to the mainland by now.”

Levi said, “C’est nécessaire that we examine the corpses from the ship, so perhaps you take the boy with you, non? Already he have seen too much death.”

Trounce sighed. “Lord help me, am I condemned to be Macallister Fogg for the day?”

“You brought it on yourself,” Burton said. “Consider your nursemaid duty a retribution for blackening my eye.”

“Humph!” the Scotland Yard man responded. He gestured for Bram to follow, and departed.

“Why do you wish to examine the dead, Monsieur Levi?” Burton asked.

“We know the volonté of Perdurabo need a body, non? And the logbook indicate he possess John Judge.”

“That is how I understood it, yes.”

“I wish to perform an experiment. Perhaps some who lie in the church hall, they are his victims. A theory I must test. You will forgive me if I say nothing more about it? There is much to consider; much to research before I can be certain that what I think is correct.”

“Very well. May I assist?”

“Oui. I will show you what is required.”

After fortifying themselves with strong coffee, Burton, Levi, and Swinburne visited the High Street, where the Frenchman purchased two strings of garlic from a grocery shop and three pocket mirrors from an ironmonger’s. They continued on until they reached the church hall. Burton showed his authority to the county coroner and Moelfre’s rector, who were seeking to establish the identities of the many dead. “Go and rest awhile,” he told them. “There are certain facts I need to establish and I’d prefer it if my companions and I were left undisturbed until we’ve finished.”

The two men, having laboured for many hours, didn’t resist, and gratefully exited the hall to fill their lungs with fresh air.

“Now, monsieur,” Burton said. “What do we do?”

Levi approached the nearest body and pulled the shroud back from it, revealing the grey features of a middle-aged woman.

“Observez.”

Twisting a garlic bulb from its string, he crushed it in his hand and extracted one of its cloves. This he snapped in half and rubbed around the corpse’s nostrils.

“Like so,” he said. “And now this.”

He put his thumb to the woman’s eye and pulled up its lid, then held the pocket mirror in front of it. After a minute had passed, he stepped back and said, “We must the same thing do with every cadaver.”

“What a thoroughly outré operation,” Swinburne exclaimed. “What is its purpose?”

Levi looked down at his diminutive companion and answered, “We must identify any corpse that does not realise it is dead.”

The poet hopped on one leg and jabbed his elbows outward, dancing like a puppet with tangled strings. “This is beyond the bounds!” he squealed. “It’s diabolical! Give me a mirror. How can the dead not know they are dead? You’re as nutty as a fruitcake! Pass the garlic. Completely batty! What should I look for?”

“Toute réaction.”

“Any reaction? Barmy! Bonkers! Mad as a March hare!”

Having thus expressed his doubts, the poet got to work and, with silent efficiency, moved from body to body, testing each as instructed.

It took the three of them a little over two and a half hours to complete the procedure, and at the end of it Levi proclaimed himself satisfied that none of the dead harboured any doubts as to their condition.

Swinburne leaned close to Burton and whispered, “Are you absolutely positive he hasn’t a screw loose?”

“He’s as sane as you and me, Algy. Well, as me, anyway. I must admit, though, I’m intrigued to know what it was all about. No doubt he’ll explain when he’s ready.”

They left the church hall with the stench of death in their nostrils and returned to the pub where, an hour later, Trounce and Bram Stoker joined them for an early lunch.

The morning had robbed Burton and Levi of their appetites, and they picked unenthusiastically at their food. Swinburne, by contrast, ate with gusto and downed ale without restraint.

“There are no trains off the island,” Trounce reported, “and services on the mainland won’t resume, they say, until tomorrow. I’m afraid we’re going to have to kick our heels here for another day.”

Burton muttered an oath. It was the last thing he wanted to hear, but there was no other option, so he spent the afternoon impatiently reading and re-reading the log, furiously smoking cigars, and indulging in a vigorous walk along the coastline.

Levi, meanwhile, sank into such a deep contemplation that he became utterly unresponsive to conversation; Swinburne worked on his poetry and remained surprisingly sober; and Trounce and Stoker helped the local constabulary to collect the many hundreds of gold coins that were still washing ashore, and which, if the authorities accepted the rector’s suggestion, would be used to help support the many women who’d soon receive the terrible news that they’d been widowed.

After what, for all of them, proved a fitful night’s sleep, the detective inspector again visited the telegraph office and this time returned with the much more welcome news that although the island’s railway tracks remained blocked, those on the mainland had, for the most part, been cleared of debris.

“How about I commandeer police velocipedes?” he suggested. “We could cross the bridge to the closest town—Bangor, I believe—and catch a train from there.”

This was agreed, quickly arranged, and by half-past one the party was speeding eastward, with Bram balanced on Trounce’s handlebars. Just over an hour later, they arrived in Bangor and, finding that lines had been cleared, boarded a small train bound for Stoke-on-Trent. By four, they’d caught the Liverpool-to-London Atmospheric Express. The pumping stations blasted the carriages along at a tremendous velocity, and with the journey punctuated by just three stops—Birmingham, Coventry, and Northampton—they were back in London by eight in the evening.

A thick fog enshrouded the city. Flecks of soot—“the blacks”—were drifting through it.

“I shall go to Chelsea,” Swinburne announced. “I have my new digs at Rossetti’s place on Cheyne Walk. Number sixteen.”

Burton addressed Levi, who’d been unusually quiet and self-absorbed since their departure from Anglesey. “Monsieur, you are welcome to my spare bedroom, unless you’d prefer a hotel, in which case I can recommend the Saint James.”

“If it is no inconvenience,” the Frenchman said with a bow, “I stay with you. There is much to discuss.”

“Very well. And you, lad—” Burton ruffled Bram’s hair. “You’re a useful little blighter to have around. What say you to permanent employment as my button-boy?”

“A page, is it?” Bram replied. “You’ll not have me wearing a uniform!”

“That won’t be necessary. But we’ll smarten you up, and you’ll take weekly baths.”

“By all that’s holy! You’ll be a-jokin’ o’ course!”

“Not a bit of it. What do you say, nipper? Can you behave yourself and do as my housekeeper tells you? You’ll have a proper bed to sleep in, daily meals, and plenty enough pay to satisfy your craving for penny bloods.”

“Well now, since ye put it like that, I could give it a try, so I could.” The boy looked at Trounce. “That is, unless Mr. Fogg is requirin’ me services.”

Trounce muttered, “I’ll know where to find you if I need you, lad.”

“Aye, that you will. It’s set, then. A pageboy I’ll be.”

They left the station, hailed cabs, and went their separate ways.

“If Perdurabo’s volonté has occupied John Judge’s body,” Burton said to Levi as their growler advanced cautiously through the pall, “then he has no need to build one. Why, then, the taking of Darwin and Galton? Why the interest in Eugenics?”

“I must research,” Levi said. “I must read.”

Burton grunted. “And in the meantime, I have to wait for either the police to find Judge or for him to find me.”

Half an hour later, the growler stopped, the driver knocked on the roof, and they disembarked. Burton peered up at the man, who was but a shadow in the dense haze, and said, “How much?”

“On the ’ouse, guv’nor!” The cabbie leaned down until his face was visible. He pushed up his goggles, gave a grin and a wink, shouted, “Gee-up!” and sent his vehicle careening away.

“Penniforth!” Burton yelled. He started after the growler but had run only a few steps before it vanished into the gloom.

A police constable materialised at his side, stepping out of the eddying pea-souper.

“Trouble, Sir Richard?”

“No, not really. You know me?”

“Detective Inspector Slaughter has posted me to Montagu Place to keep an eye on things, sir. I understand there’s some threat to you.”

“I see. Well, thank you. I’ll be sure to shout if I need your assistance, Constable—?”

“Krishnamurthy, sir. Goodnight.”

On Friday morning, Eliphas Levi immersed himself in Burton’s library while his host attended to his correspondence, which included the usual flood of letters from New Wardour Castle, plus a summons from Edward.

After composing a reply to his fiancée, Burton made his apologies—Levi was happy to remain and continue with his reading—then stepped out of the house and yelled at a hansom he vaguely perceived trundling through the miasma. He checked its driver wasn’t Penniforth, then opened its door and was about to climb in when Constable Krishnamurthy called from the opposite pavement. “I’m under orders to keep guard over number fourteen, sir, but if you’d like me to accompany you—?”

“No, Constable, keep to your sentry duty. I don’t expect to be gone for long.”

He boarded the vehicle. “The Royal Venetia Hotel, please.”

The murk made it slow going, enfolding the city in such gloom that gas lamps remained lit, hovering dimly like chains of tiny depleted suns. It took an hour to reach the Strand. The thoroughfare had returned to its normal state; the huge sewer tunnel was covered over and a new road surface laid. Bazalgette’s workmen were now at Aldgate, digging their way ever closer to the East End—the “Cauldron”—and its teeming hordes of villains and beggars.

Grumbles ushered Burton into his brother’s presence.

The minister of mediumistic affairs was in his red dressing gown and customary position. There was a cup of tea and a stack of documents on the table beside his armchair. He was holding a sheaf of papers, which he put down as Burton entered. “You look as if you’ve been trampled by a herd of cattle. It’s a considerable improvement over when I last saw you.”