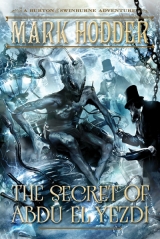

Текст книги "The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанры:

Детективная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“That’s the Cauldron,” Swinburne said, watching the distant smoke mushrooming over the city. “The flood must have pushed the bomb down to the intercepting sewer and all the way there.”

“The eleventh hour,” Burton murmured. “The end of Crowley. The signing of the Alliance.”

Swinburne jumped into the air and yelled, “Hurrah!”

Burton looked up at the Orpheus, drifting nearby high over Green Park. “Perhaps I should have Lawless take me back to Africa,” he muttered. “For a rest.”

They returned to Battersea Power Station and were met by Nurse Nightingale. “He has passed,” she said. “Do you want to see him, Sir Richard?”

“Look upon my own corpse? No, Nurse, I could not bear to do that.”

Sadhvi Raghavendra, Thomas Honesty, and Daniel Gooch arrived with the DOGS trailing behind. One of Gooch’s mechanical arms was swinging loosely, having been damaged by a bullet. Many of his men were clutching wounds.

“They surrendered,” he said. “Detective Inspector Trounce is rounding them up. Krishnamurthy and Bhatti are helping. Galton was among the Enochians. No doubt he’ll go back to Bedlam. Crowley?”

“Drowned and blown to pieces,” Burton replied. “I’m sorry about Brunel.”

“Oh, he’ll be fine. We’ll dredge him up and put him back together again. His consciousness will be intact, preserved in the diamonds.”

The king’s agent nodded and turned to Nightingale. “Will you see to Algy? He’s putting a brave face on it, but he’s been pretty badly knocked about.”

“There’s nothing wrong with me,” the poet protested, “that a swig of brandy won’t put to rights.”

Nightingale regarded his tattered form and said, “You need alcohol rubbed into your wounds, not poured down your throat.”

“Will it sting?”

“Yes, a lot.”

“Then I insist on both.”

While the nurse got to work, assisted by Raghavendra, Burton washed, borrowed clean clothes, and departed the station in a rotorchair. He flew across the river and followed it eastward. Ahead, the Cauldron was ablaze and thick plumes of smoke were curling into the air. Just when it was needed most, the rain had stopped, and with nothing to oppose the conflagration, it was spreading with alarming rapidity.

He set down in the yard at the back of the Royal Venetia Hotel and was a few minutes later knocking on the door of Suite Five. Grumbles answered and chimed, “Good morning, sir.”

Burton ignored him, pushed past, and entered his brother’s sitting room. Edward, as ever, was in his red dressing gown and creaking armchair. He looked up from a piece of paper and said, “Ah, it’s you. I’m supposed to be at the ceremony but I’ll be damned if I—Great heavens! What on earth has happened? You look positively ghastly. Grumbles, give my brother some ale.”

Burton suddenly felt so fragile that he barely made it to a chair. He collapsed into it and weakly accepted the glass from the clockwork man. He mumbled, “Unlike Swinburne, I regard it as a little early in the day for alcohol,” before downing the pint in a single, long swig.

“That was my last bottle and I don’t know when I’ll lay my hands on more,” Edward said, somewhat ruefully. He looked his sibling up and down and shook his head despairingly. “Gad! Every time you set foot in this room you look worse than the last. Has your current state anything to do with this?” He held up the note he’d been reading when Burton had entered. “It arrived a couple of minutes before you. Apparently the detonation that shook the city a little while ago was an explosion. A very large one. In the East End.”

Burton rubbed his side and winced as his ribs complained. “Yes, I know,” he said hoarsely. “It marked the end of the case. Abdu El Yezdi is dead, and I was right—you are a secret weapon, Edward, but not for the purpose I envisioned.”

The minister’s face paled. He laced his fingers together, rested his hands on his stomach, and regarded his sibling, waiting silently for further explanation.

Burton told the whole story.

For three days, the conflagration raged through the Cauldron. The bomb had exploded beneath the Alton Ale warehouse and its flames rapidly jumped from dwelling to dwelling, consuming the wooden shacks and slumping tenements, destroying everything between Whitechapel and the Limehouse Cut Canal, Stepney, and Wapping. It was the worst blaze the city had experienced since the Great Fire of 1666, and just as that disaster had rid the city of the plague, so this one cured it of the infestation of strigoi morti. The un-dead burned to ash in their hidden lairs, unable to escape in the daylight. Many innocents also perished, but the death toll was far less than it might have been due to the mass exodus of the previous days.

“I suppose it will work out for the good,” William Trounce mused. He was sharing morning coffee with Burton, Swinburne, Levi, Sister Raghavendra, and Slaughter in the study at 14 Montagu Place. Five days had passed since the death of Crowley. “The district can be rebuilt. Better housing, what!”

“Brunel has an idea for a new class of accommodation,” Burton said. “Something he calls a high-rise.”

“What is it?” Swinburne asked.

“I don’t know, but the name suggests a variation of the old rookeries.”

“Lord help us,” Trounce put in. “Are we going to pile the poor on top of one another again?” He shook his head. “Never let the DOGS run free. They have no self-control.”

“Monsieur Trounce,” Levi said, “have the police discover le cadavre of Perdurabo?”

“No, and we probably won’t. The crater where the Alton Ale warehouse stood is still smouldering—too hot to get anywhere near—and anyway there’ll be nothing left of him, I’m certain.” The detective frowned and sipped his drink. “By Jove, a strange coincidence, though. Do you know who owns the Alton breweries?”

“Non. Who?”

“The Crowley family. Three of them were killed by the blast.”

Burton raised his eyebrows. “Are you suggesting one of them might have been Perdurabo’s ancestor?”

“It’s possible. The surname isn’t particularly common.”

“So Aleister Crowley chose to invade our history because he didn’t exist in its future, and in doing so he became the reason why he didn’t exist.”

“That makes my head hurt,” Trounce groaned.

“A paradox,” Swinburne announced gleefully. “I like it. There’s poetry in it.”

“We must prepare ourselves for further such ironies and enigmas,” Burton said. “The king has approved Edward’s proposition. My brother is now the minister of chronological affairs and we, along with Brunel, Gooch, Krishnamurthy, Penniforth, Bhatti, and Babbage make up his clandestine department.”

“I suggest we add Thomas Honesty to our ranks,” Trounce said. “He’s applied to join the Force and I’ll certainly push for his acceptance. He’s a good chap.”

Sister Sadhvi added, “I suppose the poor fellow finds the prospect of groundskeeping rather tame after what he’s been through.”

Detective Inspector Slaughter gazed into his glass of milk and muttered, “He should be warned that Scotland Yard will play havoc with his innards.”

Despite the presence of the clock on the mantelpiece, the king’s agent reached into his waistcoat pocket and pulled out his chronometer, which had been retrieved from the Norwood catacombs when the police liberated Darwin and Lister. He opened it and looked at the lock of hair in its lid.

In some histories, Isabel was still alive.

Somehow, there was a modicum of comfort in that.

He said, “They’ll be here at any moment.”

No sooner had he spoken than carriages were heard pulling up outside. Eliphas Levi rose and crossed to the window, peered out, and said, “Oui, ils sont arrives.”

The party put on their coats and hats and left the house. Burton carried with him a Gladstone bag. There were three steam-horse-drawn growlers outside, and a hearse. Montague Penniforth was driving the lead vehicle, which held Nurse Nightingale, Daniel Gooch, Shyamji Bhatti, and Maneesh Krishnamurthy.

Burton and his fellows climbed into the empty carriages and the procession set off. It turned into Baker Street and followed the thoroughfare down to Bayswater Road, then proceeded westward all the way to Lime Grove before steering south, crossing the river below Hammersmith, and heading west again toward Mortlake.

The journey began amid the density of the Empire’s capital—the vehicles wending their way slowly through the pandemonium of the packed streets—but ended in a quiet and quaint village on the edge of the metropolis; a place where little had changed over the past two decades.

In Mortlake Cemetery, Burton was pleased to discover that the stonemasons he’d hired had applied themselves to their commission with expertise, though he’d given them precious little time for it and the job wasn’t yet complete. Nevertheless, when finished, it would be the tomb he’d requested: an Arabian tent sculpted from sandstone with such realism that its sides appeared to be rippling in a breeze. Set in a quiet corner of the graveyard, it stood thirteen feet tall on a twelve-by-twelve base, and had a glass window in the rear of its sloping roof so the inside would always be light.

It was, he thought, rather beautiful, and most importantly of all, it was above ground.

They carried a coffin from the hearse and placed it inside the mausoleum. Burton took a string of camel bells from his bag and hung them—gently tinkling and clanking—from the front point of the structure’s roof. Swinburne recited a poem he’d composed for the occasion.

They laid Abdu El Yezdi to rest.

PRINCE ALBERT OF SAXE-COBURG AND GOTHA (1819—1861)

In the months following his marriage to Queen Victoria in February 1840, Albert was not popular with the British, who harboured a deep suspicion of Germans. However, when Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate the queen in June 1840, Albert displayed remarkable courage and coolness, which won the people over. Shortly afterward, the Regency Act was passed to ensure that he would gain the throne in the event of Victoria’s death.

ISABEL ARUNDELL (1831—1896)

Isabel and Richard Francis Burton met in 1851 and, after a ten-year courtship, married in 1861. Isabel was convinced they were destined to be together due to a prediction made during her childhood by a Gypsy named Hagar Burton.

GEORGE FREDERICK ALEXANDER CHARLES ERNEST AUGUSTUS (1819—1878)

If Queen Victoria had died in 1840, Ernest Augustus I of Hanover would have succeeded to the British throne, to be followed, upon his death in 1851, by his son, George V. Queen Victoria’s long life meant this never happened, and George V instead became King of Hanover. He was deposed when Prussia annexed the country in 1866 and spent the remainder of his life in exile.

CHARLES BABBAGE (1791—1871)

By 1859, Charles Babbage had already contributed to the world his designs for a “Difference Engine” and an “Analytical Engine” and was concerning himself more with campaigns against noise, street musicians, and children’s hoops. His increasingly erratic behaviour had perhaps been signalled in 1857 by his analysis of “The Relative Frequency of the Causes of Breakage of Plate-Glass Windows.”

THE BATTERSEA POWER STATION

The station was neither designed nor built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and did not exist during the Victorian Age. Actually comprised of two stations, it was first proposed in 1927 by the London Power Company. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (who created the iconic red telephone box) designed the building’s exterior. The first station was constructed between 1929 and 1933. The second station, a mirror image of the first, was built between 1953 and 1955. Considered a London landmark, both stations are still standing, but derelict.

SIR JOSEPH WILLIAM BAZALGETTE (1819—1891)

A civil engineer, Bazalgette designed and oversaw the building of London’s sewer network. Work commenced in 1859. The system is still fully functional in the 21st century.

ISABELLA MARY BEETON (NÈE MAYSON) (1836—1865)

Isabella Mayson married the publisher Samuel Orchart Beeton in 1856. In September 1859, they were expecting their second son (the first had died two years earlier). Mrs. Beeton became famous as the author of The Book of Household Management, published in 1861. Four years later, she died of puerperal fever, aged just 28.

BIG BEN

Big Ben is the nickname of the Great Bell in the Elizabeth Tower at the Palace of Westminster. The tower—originally named St. Stephen’s, then just “the Clock Tower”—was completed in 1858. The bell is the second to be cast, the first having cracked beyond repair. The replacement was made at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. It first chimed in July 1859 but cracked in September and was out of commission for three years.

HENRY BERESFORD, 3RD MARQUESS OF WATERFORD (1811—1859)

Nicknamed “the Mad Marquess,” Beresford’s drunken pranks made him the prime suspect during the Spring Heeled Jack phenomenon of the Victorian Age. He was killed in a horse-riding accident in 1859.

JAMES BRUCE, 8TH EARL OF ELGIN (1811—1863)

From 1857 to 1861, Lord Elgin was High Commissioner to China, during which time he organised the bombing of Canton, oversaw the end of the Second Opium War, and ordered the looting and burning of the Yuan Ming Yuan (Old Summer Palace). In 1860, he put his signature to the Convention of Beijing, which stipulated that Hong Kong would become a part of the British Empire.

In 1859, Lord Elgin and his secretary, Laurence Oliphant, were in Aden, en route to London, when Burton and Speke arrived at Zanzibar, having completed their expedition to Africa’s Central Lakes. Elgin offered to convey them home aboard his ship, HMS Furious. In the event, with Burton being too sick to travel, it was only Speke who accepted the offer.

ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL (1806—1859)

Brunel was, by 1859, the British Empire’s most celebrated civil engineer, responsible for building the bridges, tunnels, dockyards, railways, and steamships that revolutionised transport during Victoria’s reign. On 5th September 1859, he suffered a stroke and died ten days later, aged 53.

EDWARD JOSEPH BURTON (1824—1895)

Richard Francis Burton’s younger brother shared his wild youth but later settled into Army life. Extremely handsome and a talented violinist, he became an enthusiastic hunter, which proved his undoing—in 1856, his killing of elephants so enraged Singhalese villagers that they beat him senseless. The following year, still not properly recovered, he fought valiantly during the Indian Mutiny but was so severely affected by sunstroke that he suffered a psychotic reaction. He never spoke again. For much of the remaining 37 years of his life, he was a patient in the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum.

CAPTAIN SIR RICHARD FRANCIS BURTON (1821—1890)

On 4th March 1859, Captain Richard Francis Burton and Lieutenant John Hanning Speke arrived at Zanzibar having completed their two-year expedition to the Central Lake Regions of Africa in search of the source of the Nile. While Burton recuperated, Speke sailed for London and there took the honours for the expedition’s success, thus beginning a feud that would last for five years and end with Speke’s death. Burton’s career would never recover. By 1861, he had married Isabel Arundell and accepted the consulship of the disease-ridden island of Fernando Po. He was not knighted until 1886, just four years before his death.

THE CANNIBAL CLUB

In 1863, Burton and Doctor James Hunt established The Anthropological Society, through which to publish books concerning ethnological and anthropological matters. As an offshoot of the society, the Cannibal Club was a dining (and drinking) club for Burton and Hunt’s closest cohorts: Richard Monckton Milnes, Algernon Swinburne, Henry Murray, Sir Edward Brabrooke, Thomas Bendyshe, and Charles Bradlaugh.

ALEISTER CROWLEY (1875—1947)

Aleister Crowley, called by the press of his time “the wickedest man in the world,” was an influential occultist, author, poet, and mountaineer. He was a great admirer of Sir Richard Francis Burton and Algernon Swinburne.

CHARLES ROBERT DARWIN (1809—1882)

After decades of work researching and developing his theory of natural selection, Darwin had only partially written up his thesis when, in June 1858, he received a paper from Alfred Russel Wallace that outlined the same hypothesis. For the next year, Darwin, suffering from ill-health, rushed to produce an “abstract” of his work, so that he, rather than Wallace, might claim to be the theory’s architect. On the Origin of Species was finally published on 22nd November 1859. It was an instant best-seller and has become one of the most influential books in history.

BENJAMIN DISRAELI, 1ST EARL OF BEACONSFIELD (1804—1881)

Having already succeeded as a novelist, Disraeli entered politics in the 1830s. In 1835, he outlined the principles for the Young England political group, which sought to advance an idealised version of feudalism, supported the idea of an absolute monarch, and promoted the raising of the lower classes. The group lasted until 1847. Disraeli achieved greater prominence in the mid 1840s, when, in light of the Great Irish Famine, he led opposition to the repeal of the Corn Laws. In 1852, Lord Derby appointed him chancellor of the Exchequer. His subsequent budget led to the fall of the government. Nonetheless, Disraeli occupied the post again from 1858 to the middle of 1859, before eventually becoming prime minister throughout 1868, and again from 1874 to 1880.

CHARLES DODGSON (1832—1898)

Better known as Lewis Carroll, by 1859 Dodgson was contributing stories and poetry to various magazines and had become friendly with the Pre-Raphaelite artists, including Gabriel Dante Rossetti. He’d also become acquainted with the Liddell family, whose daughter, Alice, would inspire his greatest work, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

SIR FRANCIS GALTON (1822—1911)

The half-cousin of Charles Darwin, Francis Galton was an anthropologist, eugenicist, explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, and statistician. Darwin’s On the Origin of Species inspired him, in 1859, to dedicate the rest of his life to the research of heredity in human beings.

Fifteen years earlier, in February 1844, 22-year-old Galton had joined the Freemasons. He rose through the Masonic degrees from Apprentice, to Fellow Craft, then to Master Mason, over the course of just four months. The records of the Grand Lodge state that: “Francis Galton, Trinity College student, gained his certificate 13th March 1845.”

Also in 1845, he suffered a severe nervous breakdown.

SIR DANIEL GOOCH (1816—1889)

After training with a number of companies, including the one run by Robert Stephenson, Daniel Gooch was recruited in 1837 by Isambard Kingdom Brunel for the Great Western Railway. He became one of Britain’s most eminent railway engineers, and later played a major role in laying the first successful transatlantic telegraph cable.

THE GREAT IRISH FAMINE

Potato blight struck Ireland in February of 1845. It caused mass starvation and disease, leading to an exodus between 1845 and 1852, when thousands of Irish citizens emigrated.

THOMAS LAKE HARRIS (1823—1906)

An American mystic and self-styled prophet, Lake preached in London in 1859, claiming his inspirations were received from an angel named the Lily Queen, to whom he was married. He dedicated one of his books, Lyra Triumphalis, to Algernon Swinburne. In the late 1860s, Harris created the Fountain Grove community in California—essentially a cult—which Laurence Oliphant joined. Oliphant gave all his money to the community and worked as a farm labourer, not properly splitting from the group until 1881.

G. E. HERNE (?—?)

Herne was a lieutenant in the 1st Bombay European Regiment of Fusiliers, who, prior to his participation in Burton’s disastrous Harar expedition, was distinguished by his surveys, photography, and engineering projects on the west coast of India. He was not involved in Burton’s expedition to the source of the Nile and was never consul at Zanzibar.

JOHN JUDGE (?—?)

An Irish survivor of the Royal Charter wreck. Described as being “of Herculean size,” he was in the forecastle when the ship broke on the rocks and was washed out to sea. Fortunately, he managed to catch hold of a spar and made his way to shore.

EDWARD VAUGHAN HYDE KENEALY (1819—1880)

Best remembered for his scandalous behaviour during the Tichborne trials of 1873, Kenealy was a barrister, writer, and self-proclaimed prophet.

ELIPHAS LEVI, BORN ALPHONSE LOUIS CONSTANT (1810—1875)

Levi was a French occultist and ceremonial magician who published his first treatise on magic in 1855. He was a major influence on Aleister Crowley.

RICHARD MONCKTON MILNES

1ST BARON HOUGHTON(1809—1885)

Monckton Milnes was a poet, socialite, politician, patron of the arts, and collector of erotic and esoteric literature. He was a supporter, not opponent, of Lord Palmerston. For many years he courted Florence Nightingale, who turned down his marriage proposal on the grounds that marriage would interfere with her dedication to nursing. Monckton Milnes is thought to have created the name Young England for the political group led by Benjamin Disraeli.

SIR RODERICK MURCHISON (1792—1871)

One of the founders of the Royal Geographical Society and its president for a considerable period, including during 1859, when the Society was granted a Royal Charter.

LAURENCE OLIPHANT (1829—1888)

An author, traveller, diplomat, and mystic, in 1859 Oliphant encouraged John Hanning Speke to claim the honours for the discovery of the source of the Nile, thus betraying Burton, whose expedition it was. In the subsequent years, Oliphant was instrumental in keeping their feud alive. During the late 1860s, he fell under the influence of Thomas Lake Harris.

JOSEPH ROGERS (1829—1897)

Born Guzeppi Ruggier in Malta, Rogers was a seaman aboard the Royal Charter. When the ship ran aground in October 1859, he managed to swim ashore, dragging a rope with him. He was injured in the attempt, but his efforts allowed a bosun’s chair to be rigged, providing a lifeline for thirty-nine passengers and crew. Rogers was awarded the RNLI Gold Medal for bravery.

THE ROYAL CHARTER

The Royal Charter was a passenger ship which, during the great storm of 1859, was wrecked on the northeast coast of Anglesey with a loss of approximately 459 lives. A 2,719-ton iron-hulled steam clipper, she had auxiliary steam engines for use in windless conditions, making her a fast vessel, able to complete the Liverpool-to-Australia voyage in as little as 60 days. On 26th October, she was completing the journey from Melbourne when the storm struck.

THE ROYAL CHARTER STORM OF 1859

On 25th and 26th October 1859, the British Isles were battered by the most severe storm of the 19th century. It caused the deaths of more than 800 people. 100 mph winds wrecked 133 ships and badly damaged another 90.

THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

The Royal Geographical Society was given a Royal Charter—official sanction—by Queen Victoria in 1859.

LORD JOHN RUSSELL (1792—1878)

An English Whig and Liberal politician, Russell was twice prime minister, serving in that capacity from June 1846 to February 1852, and from October 1865 to June 1866. In 1859, he was secretary of state for foreign affairs in Lord Palmerston’s government.

JOHN HANNING SPEKE (1827—1864)

In 1854, John Speke joined Burton’s expedition to Harar, which was attacked at Berbera. He was captured and severely wounded, but survived and, in 1857, accompanied Burton on an expedition to discover the source of the Nile. In ’58, while Burton lay ill, Speke discovered and named Lake Victoria, which he claimed as the source. The following year, encouraged by Laurence Oliphant, he raced back to London ahead of Burton and took full credit for the discovery, despite that he was a junior officer under Burton’s command. The two men engaged in a five-year-long feud, which was to culminate in a confrontational debate in September 1864. On the eve of the event, Speke died of a gunshot wound while out hunting. Some biographers claim this was an accident, others suggest suicide.

DOCTOR JOHN FREDERICK “STYGGINS” STEINHAUESER (?—?)

Steinhaueser met Burton in India in 1846 and soon became one of his most valued friends. He later served as resident civil surgeon at Aden, and treated Burton and Speke after they were both seriously injured on the coast of Berbera in 1855. Burton subsequently asked him to join the quest for the source of the Nile, an invitation Steinhaueser was keen to accept but, in the end, was forced to turn down. In 1860, he and Burton travelled together around America. This is one of the most obscure periods of Burton’s life. Not long afterwards, Steinhaueser died, quite suddenly, of a brain embolism.

COUNT SOBIESKI (1833—?)

Real name Michael Ostrog, he was a Russian-born fraudster and thief. In 1889, he was named as a suspect in the Jack the Ripper killings, but was later discovered to have been in a French prison at the time of the murders.

THE SOLAR STORM OF 1859

Also known as the Carrington Event, this was the most powerful solar storm in recorded history, which caused, on September 1st and 2nd of that year, the largest recorded geomagnetic storm. Aurorae appeared around the world and telegraph systems failed, shocked their operators, caused spontaneous fires, and in some cases mysteriously sent and received messages despite having been disconnected.

ABRAHAM “BRAM” STOKER (1847—1912)

Born in Dublin, Ireland, 12-year-old Stoker was still at school in 1859. In adulthood, he became the personal assistant of actor Henry Irving and business manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London. On 13th August 1878, Stoker met Sir Richard Francis Burton for the first time, and described him as follows: “The man riveted my attention. He was dark and forceful, and masterful, and ruthless. I have never seen so iron a countenance. As he spoke the upper lip rose and his canine tooth showed its full length like the gleam of a dagger.” Stoker’s novel Dracula was published in 1897.

WILLIAM STROYAN (?—1855)

A lieutenant in the Indian Navy, Stroyan was a talented astronomer and surveyor. He was killed by a spear-thrust, on the coast of Berbera, during Burton’s ill-fated expedition to Harar in 1855.

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE (1837—1909)

During 1859, Swinburne was temporarily rusticated from Balliol College, Oxford, for having publicly supported Felice Orsini’s attempted assassination of Napoleon III. He spent much of the year at Wallington Hall, mixing with Lady Pauline Trevelyan’s intellectual circle. It was not, however, until December 1862 that he joined Lady Pauline and her guests on a trip to Tynemouth where, according to William Bell Scott, the poet recited the as yet unpublished Hymn to Proserpine and Laus Veneris.

HENRY JOHN TEMPLE, 3RD VISCOUNT PALMERSTON (1784—1865)

Lord Palmerston lost his seat in government when Lord Melbourne was defeated in the general election of 1841. Though out of office for five years, he returned as foreign secretary under Lord John Russell and served in that capacity until 1852, when he became home secretary in the Earl of Aberdeen’s government. In 1855, he became prime minister. International intrigues forced him to resign three years later, but after just twelve months he was re-elected and served as a very popular premier until his death in 1865.

THE TOWER OF LONDON

In October 1841, a serious fire destroyed parts of the tower, including the Grand Armoury.

LADY PAULINE TREVELYAN (1816—1866)

An English painter, Paulina Jermyn Jermyn was married to Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan in May 1835. She made Wallington Hall in Northumberland a focal point for Victorian artists and intellectuals, counting among her frequent guests Swinburne and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Mark Hodder is a time traveler of limited capacity. He is restricted to forward momentum and cannot alter his speed, which is set at the breakneck pace of sixty seconds per minute. Despite these constraints, he is able to achieve the feat without mechanical assistance, though he fears this may change if he goes too far.

Mark’s voyage began on November 28th, 1962—embarkation point: Southampton, England—and has currently reached the year 2013 and Valencia, Spain. So far, the experience has not resulted in any ill-effects, other than a phenomenon wherein increased familiarity with the sensation of time travel has caused Mark’s mind to falsely report an ongoing increase in velocity.

Entertainments enjoyed during the excursion have included vast amounts of reading, writing, and studying; a good deal of contact with other time travelers; various degrees of involvement with radio, television, and film production; and an immoderate amount of eating and drinking.

Mark was at one point skilled in the operation of a bow and arrow (location: university) but has since transferred his attention to more complex technologies. He has employed the latter to create accounts that might possibly continue onward in some form after the cessation of his journey. They are: The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack (winner of the Philip K. Dick Award, 2011); The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man; Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon; A Red Sun Also Rises; and the volume you are currently holding in your hands, viewing on your device, listening to, or having streamed directly into your mind.

The aforementioned works are not instruction manuals, and Mark would like to remind his fellow time travelers that, in cases of emergency, they should consult with one another at the earliest opportunity.