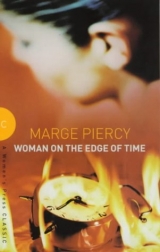

Текст книги "Woman on the Edge of Time"

Автор книги: Marge Piercy

Соавторы: Marge Piercy

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Nita’s birthday approached, the fifteenth of October. Connie begged Dolly to buy a present for her. Something preciosa. Pretty little slippers with bunnies, a soft animal with plush fur. Dolly promised, but Connie had no way to pin her down. The next time Dolly flashed in, she said Nita had had a lovely birthday. Mamб had given her a party with a cake with candles and ice cream. So Carmel still had Nita.

Connie’s tongue spoke before she could stop herself. “Dolly, it’s you who needs Nita. Sure, your mamб takes good care. But you need her with you. Without her, you don’t love yourself. You use yourself like a rag to wipe up the streets. You turn your body to money, and the money to the buzzing of death in your head.”

“I’m doing fine, Connie, real fine. Listen, Daddy and Adele say they’re coming to see you. How about that?”

“Sin duda. The day it rains money on Harlem.”

“Fнjate, I brought you some perfume. And here’s for you to get some coffee, a little something from the canteen.” Dolly kissed her cheek and pressed a wadded‑up five into her palm. “Smell the perfume, it’s the real thing. Arpege cologne. Nice, huh? It came in a set with the perfume. Splash some on now. Nice? You smell like a rose. I kept the perfume, you couldn’t hold cm to it here, the staff would swipe it A john gave it to me. He has a drugstore in Teaneck, he says he’s the manager.”

“Dolly, you’re so thin. Do you eat at all?”

“You lost weight too. The both of us. With your hair done where I get mine, you’ll look ten years younger, Connie. I’ll treat you to it when you get out Very short hair is in. I make money hand over fist now, you’ll see. You like the Arpege? It’s good to be thin, it’s chic” She pronounced it “cheek.” “When you get out, you’ll be all better and you’ll get yourself a man in no time. But that wig is ratty! How come they give you such a stupid wig? I’ll get you a good one, human hair.”

“Dolly, don’t fuss about the wig. Please get me out of here! Let me come and visit you.”

“Okay, Connie, not to worry. You’ll look great I’ll send you to my hairdresser. It’s good you lost weight, and without taking pills even! But that wig, it makes you look like a jнbara! I’ll get you a better wig so you won’t be ashamed.” Dolly kissed her. “I had something to give you. What was it? Some perfume …”

Her arms where Dolly had splashed the cologne smelled like her old caseworker, Mrs. Polcari. One case unloaded. Maybe she had had a bit of a crush on Mrs. Polcari, at the same time that she resented her youth at the age they shared, her job, her money, her home, her children, her air of being gently but firmly at all times right. She felt sophisticated thinking so about her caseworker; Luciente’s influence. Maybe she had wanted to eat Mrs. Polcari with a long spoon, like an ice cream sundae, a pineapple sundae with whipped cream and a cherry. Back in her life before they had made her their monster.

Suppose they said she could trade lives? But who would want hers? Only somebody like Dr. Redding would buy her at auction, cheap by the dozen along with five thousand chimpanzees. Now she was a chimp who smelled of Arpege. Probably the cologne would be stolen. In spite of this being a locked ward, people went in and out all day–doctors and researchers besides the staff, orderlies and aides, volunteers who filtered through the whole hospital, students, graduate students, residents, interns, the chief resident, Argent’s assistant director of research, patients’ visitors, technicians, even a patient from another ward who flitted in to sputter quickly to Tina that she was dying of cancer but nobody would believe it.

A clam in a green chair, she sat in the day room, unmoving, and all the gossip of the ward trickled through her sore mind. Somewhere in this fund of trivial bits of garbage smelling of rotting shrimp and brown lettuce must be some clue on how to find herself again, how to fight. She sat facing the bronze plaque on the wall that said the ward was named for Mrs. John Sturgiss Baylor. Baylor was Dr. Argent’s middle name. Actually it was his mother’s name, Valente said. His first wife was dead too, and his second, Elinor, was in her late thirties–a hearty good‑looking woman who seemed oddly transparent. Connie could never remember in between her appearances what she looked like. She seemed entirely beige and honey‑colored and she would come marching rapidly through the ward for some momentary consultation with Dr. Argent, striding as if across a tennis court and looking at no one, cheerful enough and utterly indifferent to them all. She was the only wife who ever came into the hospital. She was on some committee that had to do with fund raising and managing volunteers. Finally at some point she began to speak to Dr. Redding when she encountered him, giving a measured smile, but she never greeted Dr. Morgan.

Dr. Morgan had married a nurse who stayed home with their children in Rye. Nurse Roditis liked her and they had long conversations on the phone, about Dr. Morgan and his temper and his vanities and whether he was or was not having an affair with a ward secretary named Pauline. Connie found it hard to imagine Dr. Morgan having an affair with anyone, but it sounded like he was meaninglessly but frequently unfaithful, like a nervous twitch.

But patients and staff had no gossip about Dr. Redding, who had four children and had always been married to the same wife nobody had ever seen. More was known about his kids, because he talked about them. Chaz Junior was doing his residency in urology. Betsey was married, expecting. John was studying physics. Karen, the youngest, he was bitter about He said she was spoiled and he made her go to a psychiatrist. She had run away from home, from school, from him.

Patients and staff talked over the doctors constantly. What could she make of this coffee grounds of gossip? That Redding’s family had a ski and summer house in Vermont and everybody commuted back and forth except him usually. That Dr. Argent was an Episcopalian and was always hurrying to a banquet or a fund‑raising dinner for a senator or a wedding that would be in the Times.Elinor cared for neither New York summers nor New York winters, and Dr. Redding thought Dr. Argent took too many vacations.

Dr. Redding wanted Dr. Argent to invite him to some annual get‑together, some bunch of men who went up to his family’s old hunting lodge in the Adirondacks to shoot at birds or deer or whatever they shot at. Dr. Redding didn’t want to go because he liked to shoot things. He didn’t seem to like anything except his work. He wanted to go because of the men who would be there drinking and shooting. Dr. Morgan admired and envied Dr. Redding, as Dr. Redding envied but did not admire Dr. Argent. Dr. Morgan was a nervous sneak who clung to the rules on the job, who loved procedures and methodology and other such words. Dr. Redding loved power and the feeling of success. He said Dr. Argent liked too much to be a man about town. She had no idea what Dr. Argent might have loved, but he was nervous now at the brink of retirement to carry off some final prize. Redding had an ulcer, Argent had a heart condition, and Morgan lied to his wife about where he spent his evenings.

Tuesday as she was being taken to the bathroom, suddenly she felt Luciente in her like a scream. Luciente came through her like a great wound ripping open that knocked her to the floor of the ward. Then Luciente was gone. Yet she felt an after‑aura of Luciente’s presence. She knew her friend had been with her, there like lightning and gone. The attendant picked her up.

After supper she lay down while the patients were still moving around and talking, while the lights were still on all over the ward, while the laughter of the television set sounded like the pins going down in a bowling alley. She and Eddie had lived at first next door to a bowling alley in the Bronx; oh, maybe twenty blocks from Carmel’s apartment and beauty shop. She had been pregnant in that apartment: she remembered lying in the bed with the hollow rattling thunder of the bowling alley coming through the wall … . She felt Luciente approaching again. Again it was a wild careening approach, full of pain, and almost she resisted in fear; but what should she fear from Luciente? Something must be wrong. She had to find out. She went with the wave of pain, pushing over, and found herself hugging Luciente.

Luciente’s face was set with tears, twisted with agony.

“What’s wrong? What is it?”

“Person is dead!”

“Who? Who’s dead?”

“Jackrabbit,” Bee said behind her, laying his big hand on her shoulder.

“You heard today? When I felt you in my mind for a moment?”

“I didn’t know I’d touched your mind,” Luciente mumbled in a low, weary voice. “I did so now because Bee suggested you might want to attend the wake.” Gently Luciente disengaged herself and stood apart, her shoulders bent.

She touched Luciente’s cheek. “I’m glad you sent for me. Yes. I want to be with you.”

“We feel you’re family,” Bee said. “We thought you should share, if you wished.”

“I heard today,” Luciente said, and began to weep again. “It happened yesterday.” She turned away shaking. Her hands clawed the air. Her back arched on itself and seemed to collapse. Bee caught her. She struck at him, writhed, twisted back and clutched him, pressing her face into his chest.

Bee held Luciente until she had stopped shaking and then started her walking, his arm supporting her. “Come. To the meetinghouse. The wake will start.”

“Is he … Do you have the body?”

“Yes, Jackrabbit was brought by dipper this afternoon and we laid the body out. The mems, we wept over Jackrabbit this afternoon. Now it’s time for everyone.”

The room was round and about half the size it had been for the holi. Most of the younger people were sitting on mats, blankets, cushions on the floor, while the older people sat on chairs. The room was full by the time they came in and went toward the center of the circle, where Bolivar sat on the floor beside the body, his back like a flagpole. Jackrabbit lay on a board across trestles with a woolen blanket of light and dark blues thrown over him, woven in patterns of rabbits and ferns. Only his head showed. His eyes had been closed and his face wore a strange grimace, but it was obviously him: obviously Jackrabbit, obviously dead. He looked deader than the embalmed corpses of her own time, her mother painted garishly as a whore in the funeral parlor, shockingly made up.

Globes of light stood at his head and feet. Around him objects were arranged like children’s offerings: worn boots, clothing, a leather cap, a wide straw hat woven of rushes in a sea gull emblem, drawings, a pocketknife, carefully arranged piles of papers and cartridges, shiny cubes, a pillow, a woolen poncho, an intaglio belt buckle on a carefully worked leather belt, a few books, letters, a ring with a yellow stone. From what she knew of Mattapoisett, she guessed she was looking at the complete worldly goods of Jackrabbit, arranged around him in the dimly lit room.

All her family had gathered now in the innermost circle: Luciente, Bee, Barbarossa, Morningstar, Sojourner, Hawk, Dawn, Otter, Luxembourg, everyone except Barbarossa’s baby. She felt a strange shifting as if her internal earth quaked. What did she mean by calling them family? Well, something warm. They had called her to share their sorrow. They were the closest family she had now.

Everybody around her was wearing those ceremonial robes, long dresses. Bolivar, two other young people, three of middle age, and one very old also sat in the inner circle of mourners. Some people began serving coffee in ceramic mugs. Red Star, the yellow‑haired mechanic, poured hot savory coffee for them before the general serving began and returned as everyone else was served to offer more to anyone who wished.

“I’m not dressed right. My nightgown,” Connie mumbled.

Bolivar took from a pile beside the body a long shift and helped her pass it over her head. It was much too long to walk in, but for sitting it was fine. “Person had taken it out to wear in a ceremony we performed in Red Hanrahan village last month. Neglected to return the garment to the library afterward. Person was often careless.” He spoke monotonously, face blotched and strained tight.

“Oh, Bolivar. This is your second loss. Your mother Sappho and now Jackrabbit,” Luciente said. She walked over, touched her forehead to his. “Bolivar, you’re getting use to grief, and your pain must be great, recalling old pain not yet worn out.”

“Nobody gets used to grief. Yet I feel numb.”

“Before this night be over, your pain gonna loosen and come down.” Erzulia spoke, in a robe of sky blue. “I am ready to lead this ritual. Bolivar, you and Jackrabbit made so many good holies here. Many times you give us pleasure and the healing of conflict, the easing of hard edges, the vision that pick us up and carry us. I hope we able to bring you through this night. All the sweet friends and handfriends, the basemates and old family and mems. We gonna try hard to make the passing of Jackrabbit beautiful as person made other giving backs. We begin now. It gonna be done in truth and beauty and kindness.” On that last phrase her voice boomed forth. Her voice for a moment colored the air and hung there. “We gonna speak now and remember our friend. We gonna speak of the good and of the bad Jackrabbit done. We gonna remember together Jackrabbit.”

A girl stood. She began to sing:

“A hand falls on my shoulder.

I turn to the wind.

On the paths I see you walking.

When I catch up

person wears another face.

In dreams I touch your mouth.

When new friends ask me of my life

I speak of you

and words turn to pebbles

on my tongue.

I turn from them

to the wind … .”

Connie could hardly hear the ending because the girl was crying by the time she finished. “Jackrabbit was my teacher. I felt so close to per! I was angry person chose to defend while I was learning in torrents.”

Luciente too began to cry again, but Bolivar sat like a scarecrow, his freckles drawing all the color in his face to them and the rest of his skin pallid.

“I’m Arthur of Ribble, a Lancashire village in Fall River.” A heavy‑set person of forty or so with cropped light hair rose. “Jackrabbit was my child. Gave me joy and hard worry. Person was running in seven ways at once from five on. Such beauty. Such a pile of beginnings! Jackrabbit wanted to do everything. Person could not, would not choose. Instead Jackrabbit would begin to weave a rug, would launch a complicated genetic experiment, would begin studying spiders, would start glazing a namelon, would demand to be taught how holies function, would begin cartography lessons, all in one week. A month later the rug would be a beautiful fragment, the namelon would be half painted and abandoned, person would know a bit about spiders, something of how holies function, would have had three cartography lessons and would have abandoned the genetics experiment in the third generation of fruit flies. Person drove me wild! I would yell and bluster and my child would sulk and withdraw. But person would forgive me–yes, that’s the way to body it. In sunny excitement my child would forgive me and come tell me how person–then named Peony–wanted to learn theory of wind power, construct a mill, learn lithography, study Japanese and vertebrate anatomy. I comped Peony to choose something. Much pressure. I wore out just listening. I could not grasp such trying on of subjects and roles was learning also. When Peony began to think seriously of shelf diving, I bound per into making a commit. I obsessed Peony into being ashamed of flightiness–which was excessive curiosity. I didn’t do this alone. Others reacted same way. Including the head of the children’s house.” Arthur sat down.

The old person rose, still strongly made, with a squat pyramidal body ending in a head whose iron gray hair was worn in a knot. “I became Peony’s mother when that child was eight. Peony bumped on per original mother, Elima. Elima felt overwhelmed by Peony’s energy and truly began to dislike per child. So Peony and Elima brought the sticky up in council. I’m an old kidbinder and I spoke out and said I’d be feathered to have Peony for my old child. I was old then. Now I’m seventy‑nine. In our village it isn’t common for people over sixty to mother. But Peony liked the idea.”

Arthur spoke again, grinning. “Peony jumped up and down, shouting, ‘Yes, Crazy Horse is for me!’”

“I’m an old hard‑bitten comrade. I spent ten years in the war. I stiffed it all over Latin America working on reparations–I was one of the teams that worked out the details, in the early days when there were still endemic diseases raging. For a whole year after I could digest no fat. I didn’t settle down in Fall River till I was fifty‑five. I’d had a child at fifteen, live‑born child of my own body, and saw my baby die of tularemia when they loosed the plagues on us … . Peony–Jackrabbit–was like wine to me. Didn’t care for the right and wrong. I figured you grow through things. I can still remember being hungry as a child, always hungry … . What a pretty child person was–gawky, long‑limbed, awkward, but coltish and gifted in giving joy. I had only three years of mothering but years I loved. I didn’t give dandruff if Peony was irresponsible. We were each comping Peony in opposing ways. No wonder person went mad at naming. I was gobbling up every prank like candy and Arthur here was pushing the straight and narrow … .”

“What of the third mother?” Bee asked.

“In Oregon now. Gentle, quiet. Couldn’t fix Peony against our heaving and hauling,” Crazy Horse said. “Still, Jackrabbit grew strong, and rough times can shake a body down. I never met a kid I liked better.”

Arthur shook his head. “Jackrabbit used to fall by to see Crazy Horse whenever person worked near us, and we’d talk. Even last year we were arguing. Somehow we could never leave off arguing. I loved Jackrabbit, yet I think I must have spent ninety percent of the time we had insisting person was always wrong. Clipping, binding.” Arthur sat down abruptly and blew into a big orange handkerchief.

At the back someone rose to play a sad melody on a flute. The flutist played for perhaps ten minutes, joined by a guitar, a flat twangy instrument, a drum. After the others stopped, the guitar played a song many joined with that muffled blurry sound people have when they’re not trying to sing in unison:

“I feel like dry grass

combed by the wind, the wind.

I feel like last year’s grass

raked by the salty wind.

The tides creep in the marsh,

the water rises,

the water falls,

but the old grass finally breaks

under the wind.”

After the singing died into silence and they sat on for a while, White Oak rose. “I came here fourteen years ago to work in the plant genetics base just firming. Jackrabbit and I have been friends since sixmonth after person came here to be with Bolivar. Jackrabbit ate with us awhile, deciding what family to join. Especially we shared a love for the sea What I want to tell is something two–no, three years ago. Now, you know my loving with Susan‑B was not good. Never in balance. We all critted on that and tried, but it never flew and always I felt unvalued in the end. Susan‑B is gone now and I confess it’s easier for me with person living at Portsmouth. For a long time I couldn’t want to be loving with anyone, waiting for Susan‑B to want to be as close to me as I wanted with per. A long saddening. When Susan‑B left, I had to face the failure of the whole long struggle. I withdrew even more. I worked hard–”

“Fasure, day and night,” Bee said. “You coordinated and did the work of three.”

“I feared being close. My family suggested a healer, but I was too proud. Zo, one day Jackrabbit and I took out the green boat and spent all afternoon and evening on the bay. It was fine–the wind, the salt, the water. I felt loosened. I had not taken a day free in months. I know Jackrabbit sensed my mood, for person could easily catch changes. Doors opening, doors closing. Everyone had eaten. We scraped leftovers and Jackrabbit came along to my space … . How easy and insinuating person could be. Without deciding to, still addressing Jackrabbit in my mind as if person were half a child, we ended up coupling that night. After, I felt for the old knot, and it was melted. Only the feeling I’d been a great fool. I’d scorned what was easy, the affection of my own family, for what I couldn’t have. Since then I have tried to be simpler, better … . It wasn’t that Jackrabbit worked healer’s entrance, but person loosened the knot that pride kept tight. Once loosened, I couldn’t wait to bind myself again. Even I had that much sense.” White Oak smiled and sat down. Her gaze rested on the wall.

“Person’s way of insinuating into other people’s beds was not always productive,” a young person said, standing on one foot. “Jackrabbit came to me once after a dance and then never again. I felt I was an apple person had taken a bite of and spat out.”

“Person was so curious, began far more friendships than could be maintained,” Bolivar said dryly, without raising his head.

“How can you carry on about a small thing?” Connie burst out. “Can’t you forgive him for something small that wasn’t even intended to hurt?” Joined to Luciente, how strongly she could feel her pain raw against the breastbone.

Bee spoke in his deep, gentle, careless‑sounding voice. “We recall what we can. Good and ill, doings and undoings. We want to hold person entire in our minds before we begin slowly to forget.”

A short brown man rose. “Last year I studied History of Jazz at Oxford. Even there in Mississippi, they had a painting of Jackrabbit’s traveling from village to village. That’s from my home, I told them, and felt proud.”

Luciente rose, swaying. Words came in gouts. “Was good to be with Jackrabbit. I was selfish, selfish over that good. Now it’s gone. Person is gone!”

“How did it move, Luciente? Speak of Jackrabbit,” Erzulia commanded in a high, carrying voice.

“Person made me able to be … careless. Silly.”

“Was that good or bad, Luciente?”

“At first I feared maybe bad. I cramped at forgetting meetings, experiments, issues. Gradually I felt that loosening gave me energy. Jackrabbit was water, I could float. Jackrabbit was wine, making me tipsy and glad of the moment. We were always laughing. We never stopped flirting. Person was full of grace. Person made me want to know things that on my own I would never have grazed. Now, nothing …” Luciente stopped, choking into tears. She remained standing, her hands inscribing shapes on the air, but she could not sort words. Otter sat her down gently.

After a space of minutes of soft crying and shifting about, a child rose. “Jackrabbit worked with me a whole lot, teaching me how to handle a boat and swim. Person didn’t always suck patience, but person laughed a lot–not at me. Person made … even picking the Swallowtail caterpillars off the carrots fun. Person made them put out their horns … . I’ll miss Jackrabbit a lot!”

Another child stood. “Person was teaching me holi work. Now nobody will have–will ever–grasp, believe in me when I can’t do what I mean. Person made me feel my–the pictures I saw in my head were good even when they came out–so stupid!” Abruptly the child sat, red in the face.

Magdalena of the children’s house came forward on bare feet, small as a child and black as the blackest cat. “We think old people have a special kinning with children. But sometimes young people hold a strong sense of how it was, so that they stay in touch with the child inside and therefore with real children. Jackrabbit was so. Could enjoy children as people and want to work with them. Find their ideas interesting, their visions real, their problems worth mulling … . I worried about Jackrabbit’s wandering sexuality. Person knew of my mistrust and teased me. Ran circles around me. Now Jackrabbit is gone many more children will miss per than will speak of it tonight. I too will miss Jackrabbit! A good strong holi is a powerful tool of learning. Many artists who make ceremonial and artistic holies, if they turn to making instructional holies at all, do so as in a lesser medium. Condescending. They simplify … in the wrong dimensions. Children sense the falsity and turn away, bored. The holies Jackrabbit made for us we’ll use long past the lifetime that should have been pers.”

A big man, grizzled and bald, stood. “Blackfish of Provincetown, I taught Jackrabbit. There’s no keener–or more dubious–pleasure than having a student you know will surpass you. I can’t stay, I have to go back on the dipper tonight, we’re in the middle of harvest. But what a waste! Person did nothing of what person could have. Nothing. We’re all poorer.”

A person in a mottled green and brown jumpsuit rose and spoke loudly. “I want to tell you how Jackrabbit died. Then I must leave too. I wish I could stay the night … . The fighting’s been fierce. They have new flying cyborgs, can go rocket speeds and cruise at twenty kilometers … . We suffer heavy losses … .” The person in green and brown paused to look around as if to recover a lost intent. “At now, you all grasp from the last grandcil more of us are going to have to fight for a while … . Jackrabbit was no born fighter. Person would have been happier staying home. But fought well. Jackrabbit was wounded running out to move a sonic shield to protect our emplacement. Was dying when we got to per. Damage to chest and organs was too extensive for us to save the life. We blocked pain. Jackrabbit died within fifteen minutes. We corded a last message. Should I play it?”

Erzulia rapped out, “Play it now.”

Minor scufflings with equipment. Then Jackrabbit’s unmistakable voice spoke in brief, broken sentences, half swamped in crackling and background noise. “Luciente: weep and work. Was good. You have to help people prepare … . Bolivar: break open. Go to Diana for help. Finish our holi with browns, reds, greens. Glim into uprush. Earth itself moving. Armies of trees. See? Armies of trees … . Bee: bring Luciente through. Never got to mother. Mother for me … . Corolla: regret what will never fuse now … . Orion: have faith in visions and patience with matter–” The voice choked in midsentence. Only crackling followed.

The person in uniform continued apologetically: “Jackrabbit meant to give more messages, but couldn’t. We could tell person intended to speak to more of you … . At first we were trying to save per. We should have grasped at once the wounds were too severe. Otherwise we’d have started cording sooner. We wasted time while we didn’t want to admit Jackrabbit was dying. Our tardiness robbed many of you of a message.”

Bee said, “You did well. We’d rather have had Jackrabbit than any message.”

The person in uniform bowed slightly and walked out. A voice began to sing:

“The tree quivers

wetly

in no wind.

I cone upon you.

How the light breaks

like arrows

through my eyelids.”

Connie stopped listening, catching Erzulia’s gaze on Bolivar, his dry narrowed eyes and brooding forehead. Rigid he sat with his legs crossed and his head at the top of the pole of spine slightly inclined. His eyes burned. His hands lay abandoned on his thighs like a pair of old kid gloves.

Others were speaking their remembrances, recounting an episode, embarrassed or nostalgic. Otter said, “I remember stiffing it all night when a hurricane was coming, to bring in the harvest, to batten things down. How Jackrabbit kept us singing and made everything funny, even when the waves came over the sea wall and we were really scared.”

Diana and Erzulia conferred. Diana rose and came back with three women of her core. Lovers, sisters, daughters of the moon, they wore the knee‑length white tunics of healers. Their hair was bound back and they bore as decoration the crescent of the moon. Now they carried a cello, a flute, and a drum. After tuning up, they began to play, sitting to one side of Diana, who stood to sing … or keen. Her voice began softly, sobbing, wordless but musical, used like a fourth instrument higher than the cello but lower than the flute. Her auburn hair fell over one shoulder. Tall and bony and commanding, she swayed. Her voice crooned, soared, ululated, wailed, and mourned over the rhythm of the drum. Finally Erzulia rose. She cast off her blue robe and stood in something like a dancer’s leotards, black against her black skin so at first Connie thought her naked. She stood still and then she seemed to grow taller.

She began to dance, but not as Connie had seen her dance the night of the feast. She did not dance in trance but consciously, and she did not dance as herself. She danced Jackrabbit. Yes, she became him. She was tall, bony but graceful, shambling and limber, young and awkward and beautiful, talented and bumbling, pressing off at once in four directions, hopping, leaping, charging, and bounding back.

Bolivar’s head slowly lifted from his chest. He was staring. Suddenly Erzulia‑Jackrabbit danced over and drew him up. Slowly, mechanically, as if hypnotized Bolivar began to dance with him/her. Erzulia possessed willfully by the memory of Jackrabbit led Bolivar round and round. He danced more feverishly, responding, his body became fluid and elegant as he had danced that night of the feast with Jackrabbit–that night she had spent with Bee. Slowly tears coursed down her own face, perhaps more for Skip than for Jackrabbit, perhaps for both, perhaps for old losses and him too and above all for Luciente and the pain tearing her.

The music ended and Bolivar embraced Erzulia. They stood a moment clasped and then Erzulia’s body relaxed. Bolivar jumped back. “But I felt per!” he cried out.

“You remembering,” Erzulia lilted gently, wiping her forehead.

Bolivar crumpled to the ground in a spasm of weeping so sudden that for a moment no one moved to support him. Then Bee and Crazy Horse gently held him, murmuring.

“Good. At last your grief come down.” Erzulia signaled to the people who had served the coffee, and they began carrying around jugs of wine and glasses and picking up the coffee mugs. This time they served everyone else first, to let the pitch of emotion ease among the close ones.