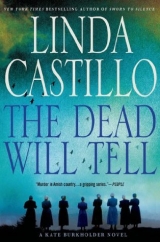

Текст книги "The Dead Will Tell: A Kate Burkholder Novel"

Автор книги: Linda Castillo

Жанры:

Мистика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To all of my readers who have read and loved the books.

Thank you.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Also by Linda Castillo

About the Author

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I’m incredibly lucky to make my living doing what I love. And while writing a book is a solitary endeavor, the publishing of a book takes the talent, the passion, and the hearts of many.

I wish to thank the team of publishing professionals at Minotaur Books for always going above and beyond to help me bring the Kate Burkholder series to life: Charles Spicer. Sally Richardson. Andrew Martin. Matthew Baldacci. Jennifer Enderlin. Jeanne-Marie Hudson. Sarah Melnyk. Hector DeJean. Kerry Nordling. April Osborn. David Rotstein. Courtney Sanks. Stephanie Davis. And of course I cannot close without mentioning the late and much-loved Matthew Shear, who is greatly missed by all. My heartfelt thanks to all of you at Team Minotaur!

I’d also like to thank Trisha Jackson, my wonderful editor at Pan Macmillan, for your always brilliant suggestions and editorial expertise. And of course for the lovely tea in Glasgow! It was a true pleasure to finally meet you.

I also owe many thanks to my dear friend and agent extraordinaire, Nancy Yost. You are the voice of reason and the architect of everything brilliant. Thank you for your keen guidance, your unwavering support, and for always leaving me with a smile.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the group of women who are my inspiration and partners in crime. You are so much more than a critique group. You are my best friends, my writing sisters, my sounding boards and rabble-rousers, and instigators of all that is fun. I cherish each of you: Jennifer Archer, Anita Howard, Marcy McKay, Jennifer Miller, April Redmon, and Catherine Spangler.

As always, I’d like to thank my husband, Ernest, for being there from the beginning and through all the craziness that is sometimes a writer’s life. I love you.

“Let the dead Past bury its dead.”

–Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “A Psalm of Life”

PROLOGUE

March 8, 1979

He dreamed of pneumatic sanders flying over the finest burled wood and full-blind dovetail joints chiseled with such precision that you couldn’t see the interlocking pins and tails. He and his datt were working on the dry sink his mamm had been pining for since spotting a similar one in the antique store in Painters Mill. He couldn’t wait to see her face when they gave it to her—

Fourteen-year-old Billy Hochstetler jolted awake with a start. He wasn’t sure what had wakened him. A noise downstairs. Or maybe the rain hammering against the roof. He lay in the warm softness of his bed, trying to get back to the dream and failing because his heart was pounding and he didn’t know why. He stared into the darkness, listening. But the only sound came from the growl of thunder and the intermittent rattle of the loose spouting outside his window. One of these days he and datt were going to get up there with the ladder and fix it.

“Billy?”

He’d just dozed off when his little brother’s whispered voice brought him back. “Go back to sleep,” he groaned.

“I heard something.”

“You did not. Now, go back to sleep before you wake everyone.”

“There are people downstairs. Englischers.”

Propping himself up on an elbow, Billy frowned at his younger brother. Little Joe had just turned eight and looked so cute in his too-big nightshirt that Billy had to grin, despite his annoyance at having been wakened. “You’re just afraid of the storm. Scaredy-cat.”

“Am not!”

“Shhh.” Billy chuckled, not quite believing him. “Do you want to sleep in here?”

“Ja!” The little boy ran to the bed and jumped as if he were diving into the creek for a swim.

As his younger brother snuggled against him, Billy heard it, too. A noise from downstairs. A thud and then the scraping of wood against wood. He looked at Little Joe. “Did you hear that?”

“I told you.”

Rolling, Billy grabbed his pocket watch off the night table and squinted at the glowing face. It was half past three in the morning. His datt didn’t rise for another hour. So who was downstairs?

Billy got out of bed and crossed to the window. Parting the curtains, he looked out at the gravel driveway, but there was no one there. No buggy or vehicle. No lantern light in the barn. The workshop and showroom windows were dark.

He grabbed his trousers off the chair. He was stepping into them when the faint murmur of voices floated up through the heat vent at his feet. He and his family generally spoke Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch at home. Whoever was downstairs was speaking English. But who would be in their house in the middle of the night?

“Where you going?” Little Joe whispered.

Billy glanced at his brother, who’d pulled the covers up to his chin. “Go back to sleep.”

“I wanna go with you.”

“Shush.” After slipping on a shirt, he opened the door and started down the stairs, already anticipating a big helping of mamm’s scrapple. He hadn’t yet reached the base of the stairs when the yellow slash of a flashlight beam played over the wall.

“Datt?” he called out. “Mamm?”

The shuffle of shoes against the wood plank floor was the only reply.

He reached the kitchen only to find himself blinded by the beam of a flashlight. He raised his hand to shield his eyes. “Who’s there?”

“Shut up!” A male voice snarled the words.

Shock sent Billy stumbling back. In the periphery of the beam, he got the impression of a man wearing a denim jacket and a knit face mask. Then rough hands gripped his arm and hauled him into the kitchen. “Get over there! On your knees!”

A hammer blow of fear slammed into him when he saw his mamm and datt kneeling on the other side of the kitchen table, their hands clasped behind their heads. On shaking legs, Billy rounded the table. Who was this Englischer? Why was he here? And what did he want?

No one spoke as he knelt beside his mamm. Leaning forward, he made eye contact with his father, hoping the older man could tell him what to do. Willis Hochstetler always knew what to do.

“God will take care of us.” His father whispered the words in Pennsylvania Dutch.

“Shut your mouth!” The man drew a pistol from his waistband and jabbed it at them. “Get your hands up! Behind your head!”

Billy raised his hands, but they were trembling so violently, he could barely lace his fingers.

“Where are the lights?” the man demanded.

“There’s a lantern,” Datt said. “Next to the stove.”

The man strode to the counter, snatched up the lantern, and thrust it at Billy. “Light it.”

Billy jumped to his feet and crossed to the counter. Feeling the man’s eyes on him, resolving to be brave, he pulled the matches from the drawer and lit the mantle. He thought about Little Joe upstairs and prayed to God the boy had fallen back to sleep.

“Give it to me.”

Billy passed it to the man, who yanked it so forcefully, the kerosene sloshed.

“Get back over there and be quiet.”

Billy took his place next to his mamm, praying they would just take what they wanted and leave.

A second man entered the kitchen, a flashlight in one hand, a pistol in the other. He was heavily built with blond hair and a bandanna over his nose and mouth. He glared at Billy’s father. “Where’s the cash?”

Billy had never seen his datt show fear. But he saw it now. In the way his eyes went wide at the sight of the second gunman. The way his mouth quivered. He knew the fear was not for his own safety or for the loss of the money he’d worked so hard to earn. But for the lives of his wife and children.

“There’s a jar,” his datt said. “In the cabinet above the stove.”

Eyes alight with a hunger Billy didn’t understand, the blond man walked to the stove and wrenched open the cabinet door. Pulling out the old peanut butter jar, he unscrewed the lid and dumped the cash on the counter.

Billy watched the money spill out—twenties and tens and fives. At least a month’s worth of sales.

“If you were in need and asked, I would have offered you work and a fair wage,” Willis Hochstetler said.

The blond man didn’t have anything to say about that.

“Mamm?”

Billy jerked his gaze to the kitchen doorway, where Little Joe stood, his legs sticking out from his nightshirt like pale little bones. Something sank inside Billy when he noticed Hannah and Amos and Baby Edna behind him.

“Die kinner.” Mamm got to her feet. “Die zeit fer in bett is nau.” Go to bed right now.

“What are you doing?” the blond man turned and shifted the gun to her. “Get back over there!”

But Mamm started toward the children. She was so focused on them, she didn’t even seem to notice that he’d spoken.

“Tell her to get down!” The man in the denim jacket shifted the gun to Datt. “I mean it! Tell her!”

“Wanetta,” Datt said. “Obey him.”

As if sensing the wrongness of the situation, Baby Edna began to cry. Hannah followed suit. Even Little Joe, who at eight years of age, considered himself a man and too old to cry.

Kneeling, Mamm gathered the children into her arms. “Shhh.”

“We’re not fucking around!” The blond man stomped to Billy’s mother and tried to separate her from the children. “Get back over there!”

“They’re babies.” She twisted away from him, put her arms around the children. “They don’t know anything.”

“Mamm!” Billy hadn’t intended to speak, but somehow the word squeezed from his throat.

“Wanetta.” Datt lurched to his feet.

A gunshot split the air. The sound reverberated inside Billy’s head like a shock wave. Like a bullet passing through water, the concussion spreading in all directions. His datt wobbled, an expression of disbelief on his face.

The house went silent, as if they were all trapped inside an airtight jar.

“Datt?”

Billy had barely choked out the word when his father went down on one knee and then fell forward and lay still. Billy held his breath, praying for him to get up. But his datt didn’t stir.

The blond man swung around and gaped at the man in the denim jacket. “Why did you do that?” he roared.

The kitchen exploded into chaos. The two men began to scuffle, pushing and shoving. Angry shouts were punctuated by Mamm’s keening and the high-pitched cries of the children. A terrible discord echoed through the house like a thousand screams.

Billy didn’t remember crawling to his father. He didn’t notice the warmth of blood on his hands as he grasped his shoulder and turned him over. “Datt?”

Willis Hochstetler’s eyes were open, but there was no spark of life. Just pale gray skin and blue lips. “Wake up.” Billy’s hands hovered over the blood on his father’s shirt. He didn’t know what to do or how to help him. “Tell me what to do!” he cried.

But his datt was gone.

He looked at the man who’d shot him. “He gave you the money,” he cried. “Why did you do that?”

“Shut up!” The man snarled the words, but the eyes within his mask were wild with fear.

“Let’s get out of here!” the other man yelled.

“Put the money in a bag!”

Somewhere in the periphery of his consciousness, Billy was again aware of screaming. His mamm or the kids. Or maybe it was him.

A third man, wearing blue jeans and a sweatshirt, his face obscured with some type of sheer fabric, entered the kitchen. He pointed at Billy. “You and the kids! In the basement. Now!”

The children huddled around Mamm, whimpering, their faces red and wet with tears.

“Don’t hurt them.” Mamm looked at the man, her eyes pleading.

Billy made eye contact with her as he started toward the basement door, urging her to follow. But as she rose, the man in the denim jacket clamped his hand over her shoulder.

The three men exchanged looks, Billy got a sick feeling in the pit of his stomach. He was only fourteen years old, but he knew that as terrible as this moment was, the worst was yet to come.

The blond man raised his gun and pointed it at Billy’s face. “Take the kids to the basement.”

Billy’s brain began to misfire. His body was numb as he herded his siblings toward the basement door. He did his best to calm them as he opened it and ushered them onto the landing. Before stepping in himself, he turned to look at his mamm. The blond man had her by the arm and was forcing her toward the living room. A second man had his hand clamped around the back of her neck. At some point, her sleeping dress had torn, and Billy could see her underclothes.

He started to step back into the kitchen, but the man with the sheer fabric over his head slammed the door. The latch snicked into place. Darkness descended like earth over a casket. Billy tried the knob, but the door wouldn’t budge. He could hear the children behind him, sniveling and whimpering again. He knew they were counting on him to keep them safe.

“Billy, I’m scared.”

“I want Mamm.”

“Why wouldn’t Datt wake up?” Hannah snuffled.

“Shush.” Staving off panic, he turned to them. The meager light coming from beneath the door illuminated just enough for him to see the shine of tears on their faces. “Little Joe, there’s a lantern on the workbench. Help me light it.”

Without waiting for a response, Billy grabbed the banister and descended the stairs. Upon reaching the dirt floor, he went left and felt his way toward the workbench where Mamm made soap. He ran his hand along the surface, knocked something over; then his knuckles brushed the base of the lantern. He located the matches next to it and lit the mantle.

“Little Joe.” Billy thrust the lantern at him. “I need you to be brave and keep an eye on your little brothers and sisters.”

The boy took the lantern. “B-but where are you going?”

“I’m going to get Mamm.” Billy hadn’t even realized what he was going to do until the words left his mouth. He darted to the ground-level window. It was too high for him to reach without something to stand on. There was no ladder. He looked around. The wood shelves were jammed with tools and jars and clay pots. Then he spotted the old wringer washing machine in the corner.

“Help me roll the washer over here.”

Choking back sobs, Little Joe handed the lantern off to Hannah and dashed to the washer. The old caster rollers dug grooves into the dirt floor as they shoved it to the window.

Billy heaved himself onto the rim of the washer tub, then stepped onto the wringer and used his elbow to break the glass. He glanced over his shoulder. In the flickering light from the lantern, he saw his siblings huddled a few feet away. A mass of wet, frightened faces and quivering lips.

“I’ll be back with Mamm,” he said. “I promise.”

Grasping the window frame with both hands, he heaved himself up and wriggled through. Then he was outside. Drizzle on his face. Somewhere in the distance an engine rumbled. Turning, he spotted taillights and saw that the car was midway down the lane. Praying he could catch them before they reached the road, he sprinted toward the car. Gravel cut his bare feet, but he didn’t feel the pain. Hot breaths tore from his throat. He didn’t know how he was going to stop them. Didn’t have a plan. All he knew was that he couldn’t let them take his mamm.

The car was nearly to the road when Billy caught them. He ran alongside the vehicle, slapped his palms against the window. “Stop! Stop!”

The tires made a wet concrete sound in the gravel as the car skidded to a halt. Billy stopped outside the driver’s door. “I want my mamm!”

The door swung open. He saw movement inside. Mamm trying to claw her way out of the backseat. “Billy! No! Run! Run!”

The driver punched him in the face. Billy’s feet left the ground. Pain zinged along the bridge of his nose. He landed on his back, head bouncing against gravel, his arms splayed above his head. Vaguely he was aware of mud soaking through his shirt. The sound of tires crunching over gravel. The smell of exhaust.

Groaning, he struggled to his hands and knees. Panic leapt inside him as the car turned onto the road. “Mamm!” he screamed.

He was thinking about pursuing the car when he noticed a strange orange glow against the treetops. Puzzled, he turned toward the house. Horror froze him in place when he saw the yellow flicker of a fire. Then he remembered the lantern.

A scream unfurled in his chest; then he was running full out toward the house. He tore around the side yard toward the basement window he’d crawled out of. Terror burst inside him when he saw smoke pouring out.

“Little Joe! Hannah!” Billy dived onto his belly, jammed his head through the window. Heat singed his face and burned his eyes. Ten feet away, a thousand yellow tongues licked at the ceiling. He could smell the acrid scent of burning plastic.

Billy looked around wildly. “Help!” he screamed.

Swiveling, he shoved both legs through the window, but the heat and smoke sent him back. He could smell his clothes singeing. Feel the terrible heat blistering the soles of his feet.

He called out again, but there was no response.

Only the hiss of smoke pouring through the window and the bellow of the flames as they devoured the house from the inside out.

CHAPTER 1

Present day

It had been a long time since he’d closed down a bar, especially a dive like the Brass Rail Saloon. The music was too loud, the liquor was bottom-shelf, and the crowd was too young and rowdy to do anything but give him a headache. It was the last kind of place you’d find a man like him. The last kind of place he wanted to be. Tonight, it suited his needs to a T. The place was dark and anonymous—and no one would remember him.

He’d received four notes so far, each becoming progressively more disturbing. He discovered the first in his mailbox last week. I know what you did. The second was taped to the windshield of his Lexus. I know what all of you did. He found the third note lying on the threshold inside the storm door off the kitchen. Meet me or I go to the police. Each note was written in blue ink on a sheet of lined notebook paper that had been torn in half. He’d found the fourth note earlier this evening, taped to the front door. Hochstetler farm. 1 a.m. Come alone.

At first he’d tried to convince himself he didn’t understand the meaning of the messages. There were a lot of crazies out there. He was a successful man, after all. He had a nice home. Lived a comfortable lifestyle. Drove an expensive car. In the eyes of a few, that made him fair game. A target because someone else wanted what he had, and they were willing to do whatever it took to get it.

He’d crumpled the notes and tossed them in the trash. He’d done his best to forget about them. But he knew the problem wasn’t going to go away.

I know what all of you did.

Someone knew things they shouldn’t. About him. About the others. About that night. They knew things no one could possibly know.

Unless they’d been there, a little voice added.

He’d racked his brain, trying to figure out who. There was only one explanation: Someone was going to blackmail him. But who?

Then two nights ago, he saw her, walking alongside the road near his house. But when he’d stopped for a better look, she was gone, leaving him to wonder if he’d seen anything at all. Or maybe it was his conscience playing tricks on him.

It had been years since he spoke to the others. But after receiving the third note, he’d done his due diligence and made the calls. None of them admitted to having received any sort of suspicious correspondence, but promised to let him know if that changed. If any of them knew more than they were letting on, they didn’t let it show.

After finding the latest note, he’d gone about his business as usual the rest of the evening. He’d ordered Chinese takeout and watched a movie. Afterwards, he’d broken the seal on the bottle of Macallan Scotch whisky his daughter gave him for Christmas two years ago. At eleven thirty, restless and edgy, he’d opened the gun cabinet, loaded the Walther .380 and dropped it into the inside pocket of his jacket. Grabbing the keys to his Lexus, he drove to the only place he knew of that was still open: the Brass Rail Saloon.

Now, sitting at a back booth with chain saw rock echoing in his ears and two shots of watered-down Scotch burning a hole in his gut, he stared at the clock on the wall and waited.

I know what all of you did.

Watching two young girls who didn’t look old enough to drink head toward the dance floor, he tugged his iPhone from his pocket and scrolled down to the number he wanted. It was too late to call, especially a man who was little more than a stranger to him these days, so he drafted a text instead.

Meet is on. Will call 2 let you know outcome.

He sat there for a moment before pressing Send, staring at the phone, assuring himself there was no way anyone could know what he’d done. It had been thirty-five years. A lifetime. He’d married, built a successful real estate firm, raised four children, and gone through a divorce. He was semi-retired now. A grandfather and respected member of the community. He’d put that night behind him. Forgotten it had ever happened. Or tried to.

Someone knows.

A knife-stab of dread sank deep into his gut. Sighing, he dropped the phone back into his pocket and glanced up at the clock again. Almost 1 A.M. Time to go. Finishing his drink, he grabbed his keys off the table and then made for the door.

Ten minutes later he was heading north on Old Germantown Road. Around him the rain was coming down so hard, he could barely see the dividing lines.

“Keep it between the beacons,” he muttered, taking comfort in the sound of his own voice.

All these years, he’d believed the past no longer had a hold on him. Sometimes he almost convinced himself that night had never really happened. That it was a recurring nightmare and an overactive imagination run amok. But on nights like this, the truth had a way of sneaking up on you, like a garrote slipping over your head. And he knew—he’d always known—somewhere inside the beating, cancerous mass that was his conscience, that some sins could never be forgiven. He owed penance for what he’d done. And he’d always known that someday fate or God—or maybe Satan himself—would see to it that he paid his debt.

Gripping the steering wheel, he leaned forward so that his nose was just a few inches from the windshield. The rain drumming against the roof was as loud as a hail of bullets against tin siding. On the stereo Jim Morrison’s haunting voice rose above the roar. There was something reassuring about music on nights like this. It was a sign of life and reminded him there were other people out there and made him feel less isolated and a little less alone. Tonight, he swore to God that was the same song that had been playing that night.

Glancing away from the road, he reached down and punched the button for another station. When he looked up, she was there, on the road, scant yards from his bumper. He stomped the brake hard. The Lexus skidded sideways. The headlights played crazily against the curtain of rain, the black trunks of the trees. The car spun 180 degrees before jolting to a halt, facing the wrong direction.

For the span of several heartbeats, he sat there, breathing heavily, gripping the wheel hard enough to make his knuckles ache. He’d never believed in ghosts, but he knew there was no way in hell he could have seen what his eyes were telling him. Wanetta Hochstetler had been dead for thirty-five years. It had to be the booze playing tricks on him.

Fearing a cop would happen by and find him sitting in his car in the dead of night with his hands shaking and the smell of rotgut whiskey on his breath, he turned the vehicle around. But he couldn’t leave. Not without making sure. He squinted through the windshield, but his headlight beams revealed nothing on the road or shoulder. A quiver of uneasiness went through him when he spotted the old mailbox. The thing had been bashed in a dozen times over the decades—by teenagers with beer bottles or baseball bats—and even peppered with holes from shotgun pellets. But he could still make out the name: HOCHSTETLER.

He didn’t have a slicker or flashlight, but there was no avoiding getting out of the vehicle. He was aware of the pistol in his pocket, but it didn’t comfort him, didn’t make him feel any safer. Leaving the engine running, he turned up the collar of his jacket and swung open the door. Rain lashed his face as he stepped into the night. Water poured down his collar, the cold clenching the back of his neck like cadaver fingers.

“Who’s there?” he called out.

He went around to the front of the vehicle and checked the bumper and hood. No dents. No blood. Just to be sure, he rounded the front end and ran his hands over the quarter panel on the passenger side, too. Not so much as a scratch. He hadn’t hit anything, human or otherwise. Just his tired eyes playing tricks …

He was standing outside the passenger door when she stepped out of the darkness and fog. The sight of her paralyzed him with fear. With something worse than fear. The knowledge that he’d been wrong. That time never forgot, no matter how badly you wanted it to—and the reckoning had finally come.

Her dress clung to a body that was still slender and strong and supple. The pouring rain and darkness obscured the details of her face. But she still had that rose-petal mouth and full lips. Long hair that had yet to go gray. He knew it was impossible for her to be standing there, unchanged, after all these years. After what happened to her. After what they did to her.

“It can’t be you.” The voice that squeezed from his throat was the sound of an old man on his deathbed, gagging on his own sputum, begging for a miracle that wasn’t going to come.

Her mouth pulled into a smile that turned his skin to ice. “You look surprised to see me.”

“You’re dead.” He scraped unsteady fingers over his face, blinked water from his eyes. But when he opened them, she was still there, as alive and familiar as the woman who’d been visiting his nightmares for thirty-five years. “How—?”

Never taking her eyes from his, she opened the driver’s-side door, and killed the engine. Keys in hand, she went to the rear of the vehicle and pressed the trunk release. The latch clicked and the trunk sprang open.

“Get in,” she said.

When he didn’t move she produced a revolver and leveled it at his chest. He thought of the Walther in his pocket, wondered if he could get to it before she shot him dead.

He raised his hands. “What do you want?”

Stepping closer, she jabbed the revolver at him so that the muzzle was just two feet from his forehead. Her arm was steady, her finger inside the guard, snug against the trigger. “Do it.”

Shaking uncontrollably, he climbed into the trunk and looked up at her. “We didn’t mean it. I swear we didn’t mean it.”

He didn’t hear the shot.

* * *

Belinda Harrington stood on the porch of her father’s house and knocked on the door hard enough to rattle the frame. “Dad?” She waited a minute and then used the heel of her hand and gave the wood a dozen hard whacks. “Dad? You home?”

She’d been trying to reach him for two days now, but he hadn’t returned her calls. That wasn’t unusual; the man was independent to a fault. He’d been known to ignore calls when it suited him. Still, two days was a long time. Even for Dale Michaels.

Wishing she’d remembered to bring her umbrella, she scanned the driveway through the cascade of water coming off the roof. His Lexus was parked in its usual spot; he had to be here somewhere. She wondered if he’d found himself a lady friend and they were holed up at her place or a hotel up in Wooster. Belinda wouldn’t put it past him. Mom hadn’t come right out and said it, but she let Belinda know in no uncertain terms that fidelity had never been one of Dale Michaels’s strong points.

Cupping her hands on either side of her mouth, she called for him. “Dad!”

Her eyes wandered to the barn twenty yards away, and for the first time, she noticed the sliding door standing open a couple of feet. Though he’d never been burglarized, her father was a stickler about security. He wouldn’t leave the barn door open, especially if he wasn’t home. The initial fingers of worry kneaded the back of her neck. Had he gone out to feed the chickens and fallen? Was he lying there, unable to get up and waiting for help? He wasn’t accident prone, but she supposed something could’ve happened. What if he’d had a heart attack?

Tenting her jacket over her head, she jogged across the gravel. The rain was really coming down, and by the time she reached the barn, her shoes and the hem of her pants were soaked. Shoving open the barn door another foot, Belinda stepped inside and shook rain from her jacket. The interior was dark and smelled of chicken poop and moldy hay. A few feet away, three bantam hens scratched and pecked at the floor. Stupid things. She wondered why her father kept them. Half the time, they didn’t lay eggs and spent their days tearing up the petunias she’d planted for him last spring. Pulling her jacket closed against the cold, she flipped the light switch, but the single bulb didn’t help much.

“Dad? You out here?”

Belinda listened for a response, but it was difficult to hear anything above the incessant pound of rain against the tin shingles. There were a dozen or so places where water dripped down from the leaky roof to form puddles on the dirt floor. At least the chickens had plenty to drink.

The barn was a massive structure with falling-down horse stalls and high rafters laced with cobwebs. As kids, she and her brother had played out here; they’d even had a pony once. But neither she nor her brother had been interested in animals, and once her father had gotten his real estate company up and running, the place became a workshop where he tinkered with cars. The workbench with the Peg-Board back was still there, but the tools were covered with dust. A dozen or so boards were stacked haphazardly against the wall. The old rototiller stood in silhouette against the window where dingy light bled in. When her brother was twelve years old, he’d nearly taken his foot off with that thing.