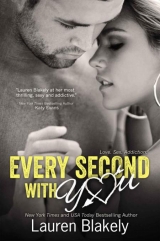

Текст книги "Every Second With You"

Автор книги: Lauren Blakely

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter Thirty-Five

Trey

I wear a tread on the linoleum in the hallway. I can’t bear to be in the waiting room. I can’t sit and fidget, and check messages on my phone like half the people in there are doing.

Debbie and Robert are there too; Debbie’s spent most of the time looking at her watch. But I’m in the hallway, and yeah, I’m looking at my phone, but I’m not texting, that’s for sure.

I’m researching.

And I’ve just learned how fucking awful preeclampsia is. I learn it can show up silently.

Check.

That its symptoms often masquerade as symptoms of other conditions.

Check.

That it can go to hell quickly.

Check.

Check.

Check.

But the worst part I learn is this: that HELLP syndrome is life-threatening. Those two words blare at me like a neon sign.

Life-threatening.

It can damage the liver. Some moms and babies die from HELLP. I read words like bleed out and renal failure and hemorrhage, and I want to shout, Make it stop!

My entire body is tight, coiled with tension. I want to hope so badly that everything will be fine, but I don’t know how anymore. Because all I can feel is the possibility of the end, and it’s fraying me inside.

Maybe I’m the curse. Maybe I bring bad luck to people I love. Maybe there’s no such thing as lightning only striking once, twice, three times. There is only things happen. And so many things are happening that it’s feels like I’m dodging blocks of concrete being dropped from windows in a cruel cartoon.

Everything I learn about HELLP is a canyon of awful. I open page after page, desperate for information, for a fact, a piece of data that can somehow soothe me. But even if I find it, how could a statistic reassure me? I am a statistic of one. One family—mine. And I have no idea how the hell my wife is doing. Or why this C-section is taking so long. Or when I am going to see her and the baby. Or if the baby is even okay. If my kid survived. Or if I am going down the route of planting another tree, and the prospect of that makes me feel as if a limb is being amputated.

I am existing in a black hole of information as life goes on around me, as nurses walk down halls and check on patients, as technicians roll on by with machines, as doctors make their rounds.

All the while, my Harley—the only woman I love, have ever loved, and will ever love—is unconscious with her belly sliced open, and her blood pressure rising, and her platelets falling, and I don’t have a clue what happens next.

Then I hear the tiniest little cry and I know.

Don’t ask me how.

Don’t ask me why.

I just know the sound of my own kid, and it stills all the jittery nerves inside me. It is like a balm to my aching heart.

I turn around to see a ruddy-cheeked nurse with wide shoulders and big hands walking toward me. She’s wearing Snoopy scrubs and carrying a baby wrapped tightly in a white blanket with blue and pink stripes.

“Mr. Westin?”

I nod.

“This is your daughter.”

The world slows to this moment; all time has become this second as she hands me my baby girl, and I hold her in my arms for the first time. Everything in me shifts, the terror fleeing my body as my heart starts to jump wildly, pumping joy and wonder through my veins.

She’s perfect in every way. Her face is still red, and she looks like she’s been screaming, but her eyes are wide open and gray, and she has little tufts of blond hair from her mom. I lean in to plant a gentle kiss on her soft baby cheek, and she feels like a complete and absolute miracle, and already I can feel—deep in my bones and my cells—that sense that she’s mine. And I don’t know where it comes from, how you can go from never having met someone to loving them in the blink of eye, but here it is. It’s happened to me.

I love her. “I love you, little girl,” I say, the first words she hears from her dad. “And your mom does, too.”

When I glance up, with a tear streaking down my cheek, the nurse is still here, a grave look etched on her sturdy features.

And I know too—in the blink of an eye—that something’s wrong with Harley.

“How is my wife?” The question tastes like stones in my mouth.

“It was a very rough delivery. Her liver nearly ruptured, and she’s lost a lot of blood, and she’ll likely need a transfusion.”

“Do you . . . do you need some?” I hold out an arm, as if she’s going to stick a needle in me and take whatever she needs for Harley.

She flashes a brief, but kind smile. “We have some.” Then she sighs. “But I want to let you know she had a seizure during the delivery.”

I stumble against the wall, clutching the baby tight as my back hits the bricks, and I sink to the floor.

“A seizure?”

The nurse bends down. “It happens with HELLP,” she says trying to reassure me, but there is nothing reassuring about a seizure. “The doctors are working on her now. They’ve dealt with this before. She’s in good hands.”

“Is she going to be okay? Is she going to live?” I choke out.

“We’re doing everything we can.”

* * *

But they don’t know if everything is enough. How can anyone know? Nobody can. One minute you are here, the next minute, gone.

One moment you are unborn; the next you are loved.

Life is strong, and life is fragile. It is beauty, and it is pain. I have both, so unbearably close to each other right now that it feels like a cruel game that some wicked master puppeteer is orchestrating.

Not once, not even in the overactive far corners of my mind, did it occur to me that I could lose Harley. I only ever believed I could lose a baby. That’s all I ever worried about. That was the fear I had to face every day, the fear I had to learn to live with every second. But never, in all those moments of staring that fear in the face, of walking past it and through it and by it and over it, did it ever dawn on me that I could have my child safely in this world, healthy and whole, and with a strong beating heart, all while Harley lies bleeding out, unconscious on a hospital table somewhere nearby, and I am helpless to do anything.

But click.

The nurse takes the baby back to the nursery for monitoring, and I pace the halls, hunting out more info. I can’t stop looking at site after site, and I don’t know why I’m doing this, sticking my finger in the fire and letting it burn. I can’t turn away, even when I start watching a video on my phone of a young father who lost his wife to HELLP. When his voice starts to break, and he lowers his head to his baby, I hit stop.

I can’t take it anymore. I can’t watch another second. I turn off my phone, and jam it into my pocket. Now my head is cluttered with facts that have done nothing to change my reality, or Harley’s. I return to the nursery to hold my child.

I cling to my daughter, clutching her in my arms so tightly. She is my anchor. She is rooting me to this earth. Without her, I’m sure I’d fall off the planet, tumble into the void of space. I reach for her hand, small and precious, and she grasps my finger instinctively, and we hold onto each other.

One half of me is singing; the other is caving in. I am empty without Harley, and I am flooded with happiness for the six pounds of joy in my arms.

Soon, Debbie and Robert find us, and sit with the baby and me. Tears flow down their cheeks too, for the new life, for their granddaughter, for everything that is lost and found at the same terrible time.

Chapter Thirty-Six

Trey

The minutes tick by, knitting themselves into an hour, and the nurse threads her way over to me in the far corner of the nursery. She tells me two things.

One, Harley’s having a blood transfusion now.

Two, she also thinks I ought to feed the baby.

Life hangs in the balance, and yet daily needs must be met.

The nurse gives me a bottle, and I feed my hungry child for the first time, and the four of us wait and wait and wait. Only the baby is immune. She sucks down the formula as if it’s all that matters in the world, her tiny lips curved around the bottle tip.

I watch her the whole time, the way she’s so focused on one thing only—eating. She’s determined to fill her belly. When she finishes, she pushes the bottle away with her lips, closing her mouth, content with the meal inside her. And still, there is no Harley. No news. No reports. Only other doctors, other nurses, other parents roaming the nursery.

Then, someone clears her throat. The doctor is in the house, but not the baby-faced guy. This doctor is older, with lines on her face, and dark blue eyes that have seen more than I want to know. I stand up, and give the baby to the nurse. My hands are shaky, and my legs are jelly. I follow the doctor into the hall, Debbie and Robert close behind.

“What’s going on?”

“I’m Doctor Strickland, the surgeon who took care of your wife.”

Took care.

That’s good, right?

I try to form words, to ask how she is, to ask if she is. But the doctor is faster than me. “She’s out of surgery, and in recovery.”

Recovery.

With that one beautiful word, relief flows fast in my veins. Doctor Strickland keeps talking, saying transfusion, and lost a lot of blood, and still not awake, but all I can think is she’s alive.

I want to grab the doctor and kiss her. I want to fall to the ground and hug her knees, and cry thank you over and over. But most of all, I want to see Harley.

“When can I see her?” I say, the words practically blasting out of my mouth.

“Not yet. She’s in the recovery room. She’s not awake. Probably not for another hour.”

The next hour is the longest of my life, and I wish I had asked for an extra dose of patience for Christmas because it would have really come in handy as I watch the minute hand move so slowly. But the nursery is a safe haven, and my daughter falls asleep on my chest, warming me with her tiny little body. Somehow, that patch of heat against my heart makes me feel as if everything is going to be okay.

Okay.

I have officially decided that’s the only word I ever want to hear anymore.

Okay.

“She’s going to be fine,” Debbie says, squeezing my shoulder. “And you two are going to get to work soon on naming this sweet little girl.”

“Yeah,” Robert says, chiming in from our little huddle in the corner. “Why don’t you have a name yet? We want to start cooing at Sally, Jane, Mandy, or something, instead of saying Hi Baby all the time.”

“Not Sally, Jane or Mandy. She’s definitely not a Sally, Jane or Mandy,” I say as I stroke her cheek softly. She releases a small, contented sigh as she sleeps so peacefully in my arms.

“Well, she needs to be something soon,” Robert says, and it feels so good to be having this conversation about names instead of about blood.

* * *

Two oxygen tubes snake out of her nostrils, coiling around the bed, and slinking up into a machine that sends breath to her nose. Her arms are covered with bandages, the crook of her elbow has been target practice for needles, and an IV drip pumps into her body. Her gown has slipped down her shoulder, her collarbone exposed, the arrow from her heart tattoo peeking out. A yellow blanket covers her, up to her chest that’s rising and falling slowly.

Her eyes are closed, though, and I would give anything for them to flutter open. They haven’t yet, and no one knows why. It’s been like this for the last two hours. I’m sitting next to her, holding her hand, hoping.

I’m doing so much hoping that there’s no room in me for anything else but this desperate, frayed desire for her to wake up. Every nerve in me is a piece in a mechanical clock, and a malevolent clock winder is turning the cranks, over and over, maniacally cackling as they start to break.

All as I wait for a sign that still hasn’t come. Harley is deep in some sort of post-surgery cocoon that no one expected to last this long.

“Any minute now, I’m sure,” an ICU nurse tells me as she checks on Harley’s vitals. This nurse has a long black braid down her back, and pink scrubs with dog bones on them. “She’s just taking her sweet time to wake up. But all her tests look normal. Her vitals are fine.”

“She was supposed to wake up two hours ago.”

“She’s taking a little longer than we thought,” the nurse says sweetly.

“But I don’t understand,” I say, and my voice sounds whiny, and I hate it, but I hate the lack of knowing more. I hate it so damn much. Because they keep telling me she should wake up, but she keeps lying here, breathing in and out, and that’s it. She’s been out of surgery for four hours, out of recovery for two hours, and she’s still not awake. She’s still not responding, not to light, not to voices, not to touch, not to the life going on around her.

Not a bat of the eyelids, not a wiggle of the fingers, not a cough.

The nurse says nothing, just shoots me a sympathetic smile.

I drop my head onto the mattress, and squeeze Harley’s hand. “C’mon Harley. I know you’re there. Just give me a sign. Squeeze my hand, or something,” I mutter.

She doesn’t squeeze my hand.

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Trey

My daughter is six hours old and nameless.

The nurses in labor and delivery would probably tease me if we were simply that couple who hadn’t picked a name yet. But the nurses don’t tease me. They call her Baby Westin, and Baby Westin has had her second feeding already, and her diaper changed, and she’s sleeping again.

She’s doing everything she’s supposed to be doing: opening her eyes, squeezing my hand, crying, sighing, eating, living.

She’s living.

And Harley is only breathing.

It’s midnight now, and the watch continues, and nothing changes except the ICU doctor. Doctor Strickland is gone, and now Doctor Whitney enters the room, introduces himself, and says he’s on rotation now.

I launch into questions. “Why doesn’t she open her eyes? Why doesn’t she move? Why is she only breathing?”

“Let me examine her,” he says calmly, and then asks me to leave for a moment, so I do, waiting in the hallway.

Pacing again.

So much pacing.

Robert and Debbie are parked in chairs outside the room. He yawns, and Debbie does the same, but no one goes, no one leaves, no one sleeps. Debbie takes another sip of her coffee, and Robert offers to get me one.

I shake my head.

“Diet Coke then?”

“No thanks.”

Doctor Whitney pokes his head out, and invites us back in.

“We thought she’d be awake by now,” he says. “And her tests are fine, her vitals are fine, everything suggests she should have woken up, but she has slipped into a comatose state.”

And I break.

I fucking break.

I shatter into a million angry pieces.

“What?”

The doctor nods, and shifts his hand back and forth like a seesaw. “She’s been teetering between unconsciousness and coma, and she remains unresponsive to stimuli, like light.”

“What the fuck does that mean?” I shout, pushing my hands through my hair, fire exploding in my brain, torching my fucking heart.

He holds up his hands, maybe in admission, maybe for protection from me. I don’t know. I don’t care. I want to kill him for telling me this.

“It means that we’re baffled as to what’s going on.”

“Baffled?” I repeat, fuming. “How can you be baffled? You’re a fucking doctor. You’re not supposed to be baffled.”

“We will continue to monitor her. We will continue to look for answers.”

“Yeah, because a coma’s not a fucking answer,” I shout. I push my fingers hard against my temple, pushing, hurting, something, anything to make this stop. I take a step closer. “Make her wake up.” Another step and he steps back, and I beg harder, grabbing for his white lab coat. “Make her wake up. Make her wake up. Make her wake up.”

“I would appreciate it if you could leave right now,” Doctor Whitney says in a wobbly voice, as he struggles to step away from me.

“Make her fucking wake up,” I say, trying to reach for him again, pleading.

Then I feel strong arms hold me back, drag me away from the doctor I want to throttle. I’m pulled out of the room, into the hall, inside the elevator, down to the lobby.

Outside. Where it’s dark and starless, and Robert has wrapped his arms around me, and my face is buried in his shirt, and the splinter in my heart hurts so much, jagged as it expands, hollowing out my insides, until all I am is this empty ache.

“I don’t know what to do,” I sob in a voice I don’t recognize anymore, a voice I never wanted to hear coming from me. “I don’t know what to do without her.”

He’s crying too. I can hear the hitch in his throat as he speaks. “All we can do is hope. That’s all we can do. Hope.”

* * *

I imagine her words. Her laughter. Her singing Bonfire Heart. I feel her hands, her hips, and her body.

But it’s all in my mind, because I wake up quickly, snapping out of a restless few minutes of sleep here on the edge of her mattress.

I wake up because there’s noise in the room. The same nurse with the long braid is back, doing her thing, checking on my wife.

“How’s she doing?”

“She’s the same, honey. Harley’s the same.”

At least she calls her by her name.

When my first brother died at birth, too young to live, my parents hadn’t named him. I was only thirteen years old, and I insisted we name him. I named him Jake.

Then came Drew. Then came Will.

They came and they went, touching down on this earth for seconds in some cases, for a few days in others. But they were named. I made sure they were named.

By all accounts, my daughter is staying. Her heart is strong, and she’s healthy, and there’s not a thing about her that baffles any doctor. But no one knows what is happening to my wife, and so no one can help her, no one can save her. She exists in the in-between. I long for her voice with every cell of my body; I’d give anything to hear a snippet of a word from her lips.

I flash back to our days and nights together, to the little moments, like playing Frogger and making her a cheesy miracle, then the bigger ones, like bringing her to the tree in New York, telling her I loved her for the first time, marrying her in the sky.

They were all amazing in their own way. All precious.

“Can I be alone with Harley?” I ask the nurse when she’s done.

“Of course, sweetie,” she says, patting me on the shoulder as she leaves.

I swallow, and the lump in my throat hurts so much, like a hard knot that will never leave. I take her right hand, and wrap my fingers around hers.

We always held hands. The night we met, I held her hand as we walked to the train station. When we were just friends, I held her hand as we walked throughout New York. Then the night I took her away from Mr. Stewart at the Parker Meridien, we practically flew out of that hotel, holding hands.

I’ve held her hands as I’ve made love to her.

I want to hold her hand for the rest of my life.

It’s such a small thing, such a simple act, but such a privilege; such a gift.

Like every single moment with her.

And I don’t know if I’ll have that luxury for much longer. So it has to matter. Every moment matters, because sometimes they are all we have.

“Harley,” I whisper, wishing this were a TV movie and she’d squeeze my fingers when she heard me say her name. But I’ve been saying her name for a long, long time tonight, and it hasn’t happened. “I don’t know if I’m going to see you again. I don’t know what’s going to happen. But you have to know that I love you more than I ever thought was possible. I have loved every second with you. You made me believe in love, you made me believe in myself, and you made me a new man. But I’m not here to talk about me, or even about you right now. Because there’s something else we need to talk about. We need to name our daughter. I can’t wait for you to meet her, Harley. She’s beautiful, and she’s so fucking healthy,” I say, my voice breaking as a salty tear hits her hand.

“Her heart works perfectly, and when you place your hand gently against her chest, you can feel it beating under your palm, and it’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever felt. She has blond hair already, and it’s soft, like a duck. But now that I think about it, I’ve never touched a duck. But I bet a baby duck has really soft hair, and so does our daughter. And she smells good too. Is that weird that I think that? But I do. She just smells sweet and powdery, and you’re going to fall madly in love with her too. You have to meet her, Harley. Just squeeze my hand, so I know you’re going to meet her, okay?”

I wait for a response, and for the briefest of seconds I’m convinced she moved, shifted a knee, an elbow, something. But the room remains still and quiet. “It’s okay if you can’t squeeze back. I know you hear me. I believe it. And I know what we need to name the baby. Her name is Hope. That’s our daughter’s name. Her name is Hope.”

Then the tears fall again relentlessly, and that hollow deepens so much more. I didn’t know there was more of my heart to carve away, but the pain tells me I was wrong. There is.

* * *

Later, I visit the baby in the nursery to feed her. After her bottle, I take a pen and add her name to the pink cardboard sign on her bassinet.

Hope Westin.

When I lay her down for her nap, I start the trek back to Harley’s room. On the way, I spot a sign I hadn’t noticed before.

I follow it, and as the sun rises I find myself in the hospital chapel. I’m not a religious person, I don’t even know if I believe in God, but I am consumed by this overwhelming need to make some sort of peace.

The chapel is a small room with wooden benches, a few plants, and pictures of serenity hanging on the wall. There are no signs of different faith in here. Only one faith, one wish—that the ones we love heal. Here, we all pray to the same god.

I walk past each picture. The first is an image of the woods in spring,with emerald green grass and mossy trees. Next, a cove on a beach, as the sun sets in a fiery orange glow. Then I stop hard in my tracks when I see a painting of a cherry blossom tree.

The design I’ve perfected over the last several months.

I touch it. I’m probably not supposed to, but nothing stops me as I trace my fingers along the trunk of the tree, then up to its branches, lush with pink blossoms, like the ones I drew on Harley that night in New York.

I marked her with a sign of what might come. I didn’t know it then. Who would have known it then? But there it was, in pink blossoms, red leaves, and brown branches on her body.

Because this tree may be a symbol of beauty, but it also signifies the fragility of life. In Japan, the cherry blossom trees bloom beautifully each year but for a short time, and their brief flurry is a reminder of how lovely, but terribly short life is.

Gone, before we know it. Before we can have all we want from it.

I want so much more from this life. I want so much more with her.

But even if she dies now, even if she leaves this earth and my arms for good, she will leave knowing love. Knowing that I loved her with every ounce of my heart, mind, body and soul. That I held nothing back. That I gave her all of myself, all of my love, all of my heart. That our love is unbreakable, that it’s for all time, and that even if it’s short, it was great. It is great. It is the greatest thing I have ever known.

She is my everything, and she will always be the love of my life, the love of my death, the love of my soul. I have loved her with no regrets, and I will continue to for the rest of my life, and even then some.

Even then some.

Because not loving her is like not existing, not breathing, not being. I don’t know how to live without loving her, and if that’s how I have to spend the rest of my days on this earth—loving a ghost—that’s how it will be.

* * *

When I walk past the nursery, Hope’s not there.