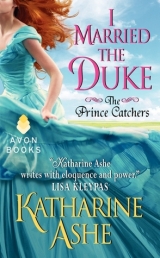

Текст книги "I Married the Duke "

Автор книги: Katharine Ashe

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“I was perfectly sincere in my fear for you when I entered that infirmary.”

Arabella’s throat got thick. “Fear?”

A knock came at the door.

“Come,” the captain called, still watching her.

“Sir,” Mr. Miles said, “Captain Masinter wishes an audience with you.”

He frowned. “Now? Before we make port?”

“His passenger insists upon it.”

“Who is his passenger, Miles?”

Mr. Miles’s voice seemed to pucker. “His lordship the Earl of Bedwyr.”

Earl?

But Arabella’s surprise was nothing to the captain’s, apparently. All amusement slid from his face. “I will pay a call on the Victory. Tell Mr. Church to ready the boat.”

“Aye aye, Captain.”

“Miss Caulfield, I will instruct Mr. Miles to return your clothing to you immediately.” He moved toward the door. Then he paused and returned to her to stand very close again. “Do not leave this cabin while I am absent. Unless Dr. Stewart is here with you, lock the door and only allow Mr. Miles to enter.” His gaze scanned her face slowly, carefully. “Do I make myself clear?”

Little hot nervous jitters slipped through her. His gaze lingered upon her lips then rose again to her eyes.

“Do I?” he repeated roughly.

She nodded. “Yes.”

“Then good day, ma’am.” He reached for his hat on the table and went from the cabin.

Arabella’s knees gave out. She sank to a chair.

An earl wished an audience with a ruffian merchant ship captain? She had never seen him, but she knew of the Earl of Bedwyr by reputation. They said he was astoundingly handsome, a seasoned gambler, and the sort of man from whom a mother should steer her innocent daughters far away. What on earth did a rakish lord want with her ship captain?

Her cheeks flushed with heat.

He was not her ship captain. His ship was merely the means to an end. In two days she would never see him again. In two days he would be nothing to her but a memory.

Chapter 5

The Duke

“The Devil take you, Luc! My men welcomed you aboard like a Messiah returning from the dead. It’s damned lowering, I say.” Captain Anthony Masinter of the Royal Navy pushed away his dinner plate and poured another full glass of wine, then refilled Luc’s as well. His moustached scowl was jocund.

Luc settled back in his chair at the fine mahogany table he had chosen for the captain’s day cabin when he outfitted the Victory for its maiden voyage six years earlier. Considerably more spacious than his quarters aboard the Retribution, it was the place from which he had commanded hundreds of sailors and half a dozen officers for over five years.

“The men remember the war and the glory enjoyed after battles, Tony. I am merely a reminder of that.”

A cabin steward worked silently about them, removing the remnants of their meal. He caught Luc’s eye.

“Blast it.” Tony’s palm came down on the table. “Even Cob here knows you’re blowing smoke. I tell you it’s damned provoking, captaining a ship full of sailors who want their old master back.”

“I would never say so, sir,” the steward said, and carried the dishes from the cabin.

“He would never say so,” Tony grumbled, wiping wine from his neat moustaches with an embroidered handkerchief. “Balderdash!”

“Speaking of smoke, shall we, Anthony?” From across the table, the Earl of Bedwyr’s voice held a studied air of indolence. Though cavalry once upon a time, after acceding to the earldom, Charles Camlann Westfall had cast off every vestige of the military. He wore now not the dashing gold-corded blue of the Tenth Hussars, but a plum cutaway coat with large silver buttons, a silk waistcoat embroidered with roses, and a mask of supreme ennui upon his face.

“Capital idea, Charles.” Tony stood and brought a box to the table, lit a cigar, and pushed the box toward Cam. “Then you don’t want the Victory?” he said loosely to Luc.

Not since he’d found another mission worth pursuing. “You know I don’t want her.”

“He couldn’t have her even if he wished,” Cam drawled.

“Right.” Tony shook his head. “The old duke doesn’t like him in the line of battle. Poor sot.” He clapped Luc on the shoulder.

“Rather,” the earl said, lifting eyes shadowed by a thatch of artfully arranged golden hair, “the old duke’s widow.” He slipped a hand draped with lacy cuff into his waistcoat and drew forth a letter bearing a wax seal. He tossed it onto the tabletop. “What say you to those tidings?”

“Luc, by golly, you’re a duke! My compliments. This calls for a toast, and a second to follow. Cob, bring the brandy!”

“He is not a duke yet, Anthony. Merely duke-in-waiting.”

Luc stared at the unopened letter in his palm. “When did it happen?”

“When did old Uncle Theodore go to his maker?” His cousin’s voice did not rise above its habitual drawl, as though coming one step closer to the dukedom himself meant nothing to him. Which it probably didn’t; Cam preferred indolence to work. “Three weeks ago, after a nasty turn for the worse. Really, Lucien, if you stayed in touch you might have known this was coming.”

The steward returned with a crystal carafe and three glasses.

Cam played absently with his gleaming watch fob, smoke curling about his shoulders. “I suppose you are still pursuing the activities you commenced when the navy ejected you?”

“Didn’t eject him. He wanted to go,” Tony said, puffing a cloud. “Noble fellow.”

The cabin was cool, the late summer wind coming off the Atlantic sifting in through the broad windows. But sweat gathered along Luc’s scar. “Why did Adina send you to tell me, Cam?” Theodore’s wife, young, beautiful, and equally as vain and vapid as her late husband, was devoted to her much older brother, Absalom Fletcher. This news would not be welcome to Fletcher. It would mean, of course, that Luc would finally return home. And so would his brother.

But Fletcher was no longer a mere cleric. Recently elevated to the episcopate, he was a powerful and influential man. The Bishop of Barris could hardly fear anything from his former wards. Nevertheless, Luc had remained at sea and Christos in France. Now, however, that would change.

“She did not send me. I volunteered.” Cam lifted a brow. “I came to commiserate, cousin.”

Tony frowned. “Now see here, Combe is a pretty place. Wouldn’t mind having a castle like that myself.”

“Luc already has a castle, Tony.”

“Not in England!”

“The title would be welcome to him, Anthony, as would the estate,” the earl murmured. “Rather, if the duchess were to lose this child like she has lost all the others, or if she were to bear a girl-child, the necessary padding of heirs to the duchy would swiftly diminish to . . . none.”

Tony choked on his brandy. “I don’t like you speaking of a man’s brother like that, Charles. Wouldn’t be surprised if Luc called you out for it. And if he don’t, I might.”

“He knows I won’t, damn his two eyes.” Luc slipped the letter into his pocket. “And you won’t either.”

“I’ll challenge the blackguard if I like, even if I do owe him a hundred guineas from that faro disaster.”

“There is a note enclosed from Adina, Lucien,” Cam said. “Are you not interested in reading our auntie’s heartfelt pleas for you to return and make it all better for her?”

“Bed her already, did you, Cam?”

Tony sprang to his feet, knocking his chair over behind him. “Damn all three of your eyes. The poor girl’s only just been widowed.”

“Sit down, you chivalrous fool.” Cam laughed with languor. “Luc is merely taunting. And the duchess is not to my tastes anyway.”

“She’s not female and married, then?” Luc finally took up his glass.

The duke had died. Long live the duke.

In the nineteen years during which Adina had been Theodore’s wife, she had lost five infants before birth. The life of the poor child she carried now was not by any means a certainty. After the fifth still birth, Theodore’s demand that Luc relinquish his command in the navy had made his concerns upon that score eminently clear.

But Luc had always assumed his uncle would recover from his illness and continue trying to make heirs. Others had grimly suggested that delicate Adina would not survive the next difficult birth, and that Theodore would swiftly take a second wife whose ability to produce heirs might meet with more success.

Now that was not possible, and because of it everything had changed.

The face of the sailor Mundy haunted Luc, like the little governess’s pleas to save the starving youth. A year after the famine now, hunger still ravaged the poor. Failed harvests the year before had decimated seed reserves, and this year’s crops were scant. He’d seen it in Portugal in the spring, France in the summer, and again in Cornwall and Devon before he departed Plymouth: peasants’ hollow cheeks, the bone-thin limbs of villagers, and children dying everywhere. Even his own family’s patrimony, a sprawling Shropshire estate, still suffered.

But he had no choice now. His current cargo must sail to Portugal without him.

Now he had one goal: he must have an heir. With the duke dead, while Adina awaited the birth of her child, the duchy was in abeyance. But if the child did not survive, or if it was a girl, Luc would inherit. He must leave his ship and return to London to find a suitable bride. The French property was modest, the Rallis title honorary; his brother Christos, who had lived at the chateau for years, could manage those. But the dukedom must never come to him. The weight of responsibility and authority would kill Christos as surely as if it were a guillotine.

Finally, Luc could no longer remain abroad. For the first time in eleven years, he must go home.

In doing so, he could see to the troubles at Combe while he still might. Theodore could not name him principal trustee to the estate. He feared that Fletcher, his uncle’s longtime friend, had been given that honor instead. Luc had only until the birth to wield authority at Combe. After the birth he would have none . . . or all.

“In point of fact, coz,” Cam said, “the duchess isn’t in any condition to be rolling about in the hay with anybody. Lovely Adina is nearly in her confinement.”

Luc’s gaze snapped up. “Already?”

“Oh, how the months fly.”

“Poor girl.” Tony shook his head. “With her record at the track, likely as not it’s all for nothing. Still, Luc’s got to hang about twiddling his thumbs waiting. Damn the aristocracy, yanking a fellow about this way and that all his life. Much better to be a commoner, I always say.”

“Your father is a baronet, Anthony,” Cam said with a slight smile.

Tony waved his cheroot about. “Nobody cares a sow’s ear about a wretched little baronet. Least of all his fifth son, don’t you know.”

“When is the child due?” Luc said.

“November.”

Less than three months. Three months, after which Absalom Fletcher could very well be the de facto master of Lycombe for years to come. Or three months until he himself became duke. It all depended on a fragile widowed duchess and her unborn infant.

Luc rubbed his scar. Casually, Cam turned his head away. But for the first time in six months, Luc did not have the urge to plow his fist into his cousin’s perfect face.

“Still and all, Luc, the poor girl could probably use a man about the place.” Tony patted the hilt of his saber. “Best you hurry home.”

“What is that monstrosity?” Cam passed an arch look over the sword. “Good God, Tony, it looks like the crown jewels.”

“Family piece.” Tony’s chest puffed out. “My great-grandfather had it as a gift from King Willie himself after his smashing success at Cherbourg, don’t you know.”

Luc stared distractedly at the glittering gems on the sword handle. A ruby caught his eye, but not nearly as large as the jewel on the little governess’s ring. He could not follow her to his chateau after all. It was for the best. He had no business courting trouble with a governess, no matter how brave and vulnerable and foolhardy she was, and no matter how her magnificent eyes looked at him with barely veiled desire and her tongue surprised him at every turn.

He swallowed the brandy in his glass, all of it, as he had the night before when he shared the darkness with a beautiful little sodden servant.

“I’ll leave the Retribution in Church’s command,” he said. “Will you head back to England immediately?”

Tony snorted. “The Admiralty has commanded that I put my ship at your disposal. The Victory sails at your leisure. Again.” He grinned upon a scowl.

Luc met his cousin’s dark gaze. Cam stared back at him, his eyes hooded.

“Why did you really volunteer to bring me the news, Cam?”

The corner of Cam’s mouth crept up. “Serendipitously, at the moment of our uncle’s demise I found myself with the pressing need to be absent from London.”

“A woman, I presume.” Luc’s scar ached. Six months ago it had also been a scandal with a woman that drove his cousin from England to France. A girl, rather. But that time Cam had surprised him. His cousin’s vice had not been what Luc imagined. By the time he understood the truth of it, of course, it was too late. His eye had been the casualty of his misjudgment.

Cam absently twirled the stem of his brandy glass. “It is always a woman that drives a rational man to behave contrary to his interests, Lucien. That you are too blind to see that”—he finally looked directly at the kerchief about Luc’s brow—“is no one’s fault but your own.”

Luc scraped back his chair and rose. The door opened and the Victory’s first lieutenant entered.

“Captain,” the sailor said to Masinter, “we’ve interrogated Mundy. He’ll admit only that he was hired in Plymouth by a man he had never seen before to find the Retribution, join the crew, and steal poison from the infirmary. He was to await further orders when they arrived in Saint-Nazaire.” He turned to Luc. “I believe he is telling the truth, sir.”

“Put the thumbscrews on the lad, did you?” Cam drawled.

“He gave you no name for the man that hired him?” Luc asked the lieutenant.

“He said he didn’t know it, sir. As to thumbs . . .” He glanced at the earl. “Mundy said that the man lacked a thumb on his left hand.”

“Thank you, Park,” Tony said. “That will be all.”

“Aye, Captain.” The officer left.

Tony scowled, this time with no pleasure. “Blast it, Luc, I don’t like a thief going freely about my ship.”

“Hold him in the bilge if you wish. I will speak with him during our return.” And learn what could be learned of the lad’s attempt at thievery. If her instincts were to be believed—her ability to read men, as she said—Mundy was not a thief by inclination but by desperation. But the poison was worrisome.

Luc went to the door. “I will see you in port, gentlemen.”

“All plans to make a sojourn to that lovely little chateau of yours are off, I suppose,” Cam said with a sigh of regret.

“Deuced shame. But old Luc’s got to take up his responsibilities after all.”

That, and avoid further private audiences with a beautiful little copper-haired servant. He would send her on to Saint-Reveé-des-Beaux and be rid of the temptation.

“DR. STEWART, WHY is the Royal Navy escorting us into port?” Arabella stood at the day cabin window, watching the ship keeping easy pace with them across the water.

“ ’Tis a great honor, lass.”

They would be at Saint-Nazaire shortly and she would be leaving the sea behind. But her nerves were stretched. She told herself it was because she was now within reach of her new position—within a day’s ride from the port, Dr. Stewart had told her. It was most adamantly not because she would be obliged to speak to Captain Andrew before disembarking. They had not spoken since he went aboard the naval ship the night before, and she was glad of it. Her dreams had not been of churning seas and thunder, but of him touching her.

She had never wanted a man to touch her before. That she dreamed of him doing so—and woke breathless, with her skirts in a tangle and skin hot—was preposterous.

“I am grateful for the care you took of me while I was chilled, Doctor. I wish I could offer you suitable compensation.”

“Ye needn’t be thanking me.” He chuckled. “And there’s no need for compensation.”

She dug into her pocket and withdrew her largest coin. “Will you accept this?”

Gently he pressed her hand away. “There be no shame in accepting charity, lass. Nor sin.”

“The sin lies in the pride that leads one to reject charity.” Captain Andrew filled the doorway to the cabin.

She was not prepared to see him again. She probably would never be. It had not been the brandy or sleep or the young sailor’s attack that muddled her when he was near before. It was rather him—simply—his strangeness and destroyed beauty and intense gaze that gentled so abruptly and grew hard again as swiftly.

“Are you a theologian now, Captain?” she said.

“I dabble in many endeavors, Miss Caulfield.”

His glimmering gaze made her want to tease too. She mustn’t. But after today she would never see him again. She would return to work and determination and her goal. “Like what?” she let herself say. “Other than sin, that is.”

He leaned a shoulder against the door frame and crossed his arms over his chest. “A bit of this, a bit of that. You know . . . apprehend jewel thieves, rescue damsels . . .” He waved a negligent hand. “The usual sorts of things.”

Dr. Stewart cast him a slanted look and went out.

Arabella drew a steadying breath. “I did not steal the ring.”

His brow went up. “I did not say that you had.”

“Why do you mistrust me about this? Have I given you any special reason to?”

He assessed her with that odd intensity that made her knees feel watery. “You are not what you appear, Miss Caulfield. The ring you bear suits your character better than the governess’s gown. Will you deny it?”

She wanted to. It was on the tip of her tongue. He spoke foolishness. She was a poor girl from a poor family. An orphan. A servant.

But when he looked at her, he made her feel like . . . a duchess.

She grappled at reality. “Why is the British Navy escorting your ship? In French waters, no less? Have you done something wrong?”

“Ah, the little duchess believes she may ask any question she wishes while refusing to answer those put to her. Interesting, though to be expected, I suppose.” He nodded toward the gun deck. “We will shortly come into port. Perhaps you would like to take in our arrival from atop.”

He gestured her through the doorway, and she went before him. But he stayed close, too close, and as she climbed the steep stair to the main deck, his hand brushed hers upon the rail.

He grasped her fingers, halting her ascent. The breeze twining down the hatchway whipped around her cloak and their joined hands.

“Sir,” she whispered, but her throat was constricted and the wind snatched away the sound.

He released her and she hurried the remainder of the way up.

The wind was strong on the main deck, and the Retribution’s sails were full like those of the naval ship close by. Sailors were active on deck.

“Have you lost your gloves, Miss Caulfield?” The captain spoke at her shoulder, low and intimate, as though they were not standing in broad daylight surrounded by dozens of men.

She turned. Color shone high upon his cheekbones and his lips were parted.

“In Plymouth,” she said, “I sold my gloves for food.”

“Food for those children you found.”

She nodded.

He stared at her mouth and his chest rose sharply, and she feared he would kiss her here before his crew in the light of day, like a man might kiss a woman of ill repute—where he wished, when he wished. For all his talk of governesses, he must believe her to be what he had first suggested in Plymouth. She was traveling alone and in possession of a ring that only a wealthy man would own. Captain Andrew had no reason to think her other than a fallen woman, or any other justification for staring at her with undisguised desire.

“I am not what you think I am.” She bit her lip. She had not meant to speak. She needn’t justify herself to him.

“I don’t believe you have the faintest notion of what I think of you. Now look behind you.”

She turned.

Arrayed like a bride on her wedding day, the estuary shone bright and sparkling in the sunshine, broad across and festooned with vessels. The near bank stretched gold and white with long, lazy beaches giving way to rows of docks cluttered with ships, banners proclaiming them from every nation on earth, it seemed.

Tucked beyond, inside the mouth of the river, the town of Saint-Nazaire was little more than a collection of quays and shipyards, with a church spire poking above the cluster of buildings that rose from the shore.

“Here amidships you are unlikely to fall overboard, duchess,” he said quietly at her shoulder. “You can release the railing now.”

She started. Her knuckles were white around the stair rail. “I . . .”

“I noticed,” he only said. “Welcome back to land, Miss Caulfield.” With a bow he strode across deck and to the helm.

Chapter 6

Two Louis

“Je suis désolé, mademoiselle,” the innkeeper said without a shadow of desolation on his narrow Gallic face. “Mais, there is no carriage in the carriage house. And one cannot fabricate a carriage from the air like the magician, can one?” His lips pursed.

Arabella’s fingers gripped the coins she had shown him, every penny she had. “This is because I am not offering to pay you more, isn’t it?”

He shook his head. “Je vous ai dit, the horses and coach, they are not available until jeudi.”

Thursday. Two days away. She could not afford to stay even a single night at the inn and also hire the carriage to Saint-Reveé-des-Beaux.

“Is there another place I may hire a carriage in town?”

“Non non, mademoiselle.” He shook his head again as though he were filled with sorrow over her plight.

“But I passed a stable walking here, and I saw a perfectly good carriage and two horses doing nothing at all,” she said firmly. “How do you explain that, monsieur?”

“There is no arguing with innkeepers in this country, my dear,” a languid voice came from behind her. “Now that they have tasted revolution, the French have little respect for anything but avaricious acquisition. Pity, really. They used to be so delightfully ingratiating.”

Golden like a god, with wavy hair and warm brown eyes, dressed in dark velvet, with draping lace at throat and cuffs, and boots that shone with champagne polish, the man standing in the doorway looked like a prince out of a storybook.

But no prince would peruse a lady from brow to toe. In comparison, Captain Andrew’s lustful stares seemed positively safe. No. That was not true. There had been nothing safe about Captain Andrew’s stares, because despite herself she had wanted them.

“Monseigneur, bienvenue!” The innkeeper bowed deeply. “How may I be of service to you?”

“You may cease distressing this lady.” He came to her. “Clearly she is in great need of assistance.”

“Which she is unlikely to accept from you.” Captain Andrew strode through the door. “I think you will find she is adamantly self-sufficient.” He bowed to her. “Madam.”

Arabella battened down on her tripping pulse. “Captain.”

The gentleman’s languid eyes went wide. “How is it, Lucien, that you have the pleasure of this diamond’s acquaintance yet I do not? It is positively criminal.”

“Miss Caulfield, allow me to—with all reluctance—introduce you to the Earl of Bedwyr,” the captain said with a sideways glance at the earl. “Cam, Miss Caulfield took passage aboard the Retribution from Plymouth.”

The earl’s mouth curved into a slow grin and he scanned her anew. “Ah, now is fully explained the presence of a passenger aboard your ship otherwise rempli des bêtes. Well done, Lucien.”

The captain accepted a key from the innkeeper.

“Festival in town, tomorrow,” came through the door before the man who spoke it. “Great guns, gents, we’re to have uncommon entertainment.” Black-haired, with moustaches that curled dramatically upon either cheek, he wore a naval uniform, the splendid plume of his tricorn draping over blue eyes. He saw her and halted abruptly.

“Well, bonjour, mademoiselle.” He swept off his hat and scraped the plume to the floor. “Sight for sore eyes, ain’t she, gentlemen?”

“It seems that Luc’s eyes are not quite as sore as ours, Anthony,” the earl drawled. “Rather, eye.”

“Miss Caulfield, this is Captain Masinter of the Royal Navy.” Captain Andrew said, coming to her side. “Tony, she is not French.”

“I don’t think Anthony is particular when the beauty is so marked,” Lord Bedwyr said with a smile.

“And she is not married,” the captain said flatly, cutting the earl a sharp glance. Then he looked at her. “Are you?”

She swallowed over the catch in her throat. The earl was frankly gorgeous, and the naval captain dashing. But standing beside the scarred, autocratic merchant shipmaster when she had expected never to see him again made her knees watery. He carried himself with absolute authority, and she had not needed to tell him she feared the sea for him to know it. She could not read him, but it seemed he could read her perfectly well.

“I am not married.”

“My sympathies, Cam,” the captain said without any show of humor, then looked down at her and his gaze glimmered. “Monsieur Gripon, have you assisted Miss Caulfield to her satisfaction?”

He had done this before, speaking to another while looking at her. It was as though he knew everyone’s attention would always be on him, waiting for his words, no matter where his attention was directed.

“Hélas, monsieur!” The innkeeper clasped his hands together as though he were in great distress. “The preparation for le jour de la fête tomorrow, you see, it has commanded toutes les ressources de la ville.”

The captain frowned.

“I wish to hire a carriage to travel to the chateau,” she said, “but he said there are none to be had, although I saw one in the stable, and horses.”

He turned to the innkeeper. “Is this true?”

“Le chariot is to bear the holy image of le roi Louis IX in the procession tomorrow night, Captain. I cannot send it away now.” The innkeeper shook his head sorrowfully. “But the mademoiselle, she does not understand.”

The captain nodded. “I see. Miss Caulfield, I am afraid in this he is probably telling the truth. How many days yet before you must arrive at your destination?”

“Five, but I should like to arrive before then.” She had no choice. She hadn’t the funds to linger even a day in Saint-Nazaire. She could not have come this far only to be thwarted now. “Will the festival last many days?”

“Only one.” Captain Masinter removed his gloves. “It is the Feast of Saint Louis, Miss Caulfield, one of those medieval crusading blokes, and ancestor to the newest Louis, don’t you know. Ought to be great good fun tomorrow.” He gave her a broad smile. “Continental Catholics, you know, throw a splendid party.”

“Why don’t you remain in town a night and enjoy the celebration, Miss Caulfield?” Lord Bedwyr said with an elegant bow. “I should be honored to escort you about the festivities.”

“I’ve no doubt you would.” Captain Andrew looked back down at her. “Miss Caulfield, if your claims of having spent time among London society are true, you will know better than to trust in Lord Bedwyr’s intentions.”

“I am barely acquainted with him, Captain Andrew. I should not presume to make a judgment.”

“Perhaps then you can trust in my word.”

“Yes, Miss Caulfield,” Cam said with a sly look at Luc, “by all means trust our friend Captain Andrew here rather than me. For all that he looks like a villain and addresses a lady like a cad, he is a noble fellow in truth, while I am but a poor man alone in an alien country, innocently seeking a lovely lady’s company for an evening stroll.” Cam’s grin slipped into the smile he had practiced upon hundreds of pretty females with enormous success.

A pale flush stole over the little governess’s cheeks.

Luc ground his molars. The rakehell always had such an effect on women. Luc had never cared. Not once.

Now he cared.

“Camlann, don’t tease the lady,” he said, unsurprised at the gravel in his voice.

“You are to be the only man allowed that privilege, I suppose?” A gleam lit Cam’s eyes.

“Captain. My lord,” she said firmly, her chin inching upward. “I would very much like it if you would not speak about me as though I were not standing here.” She turned to the innkeeper. “I will hire a chamber for tonight and tomorrow night, monsieur, in the hope that you will make the carriage available to me the following day. How much will it be?”

The innkeeper looked questioningly at Luc.

Her cheeks flamed. But her slender shoulders remained square. “I am barely acquainted with these gentlemen, monsieur, and not a member of their party. I will pay for my own room and for the carriage to Saint-Reveé-des-Beaux.”

“Saint-Reveé-des-Beaux?” Cam said with a quick glance at Luc. He stepped toward her. “Why, my dear, that is precisely my destination as well. I have an itch to see my old friend, Prince Reiner, who is in residence there as the guest of . . . Now who is that crusty old fellow that owns the castle, Tony?”

Tony lifted a brow and casually twirled a moustache between forefinger and thumb. “Don’t know if I quite recall.”

“Ah, yes, the Comte de Rallis.” Cam gestured with a lacy wrist. “Monsieur Gripon, the carriage the day after tomorrow will be on my bill. I insist. I will, of course, allow you privacy during the journey, madam. I shall ride ahead and clear the road of ruffians and knaves.” He gave her a winning smile and went to the door. “Now, Tony, why don’t we find that smart little brasserie we passed and command a roasted capon. Lucien, I trust we shall see you anon.”

“Capital idea, Charles.” Tony swept a deep bow to Miss Caulfield and departed.

She said, “You count earls and naval commanders among your close friends, Captain?”

“ ‘Friend’ loosely employed in the case of Bedwyr.”

“That, at least, is obvious. I have no intention of accepting his assistance in traveling to Saint-Reveé-des-Beaux.”

“That is probably wise.” If there were a horse or mule to be spared in town, he would send a message to the chateau and have a carriage sent for her. As soon as Miles had finished packing, he must see to it.

She studied him for a moment longer, the flush still high in her cheeks. “Good night, Captain.”

He watched her follow the innkeeper up the stairs, her back as straight as any duchess’s. He had no doubt that the young ladies she trained for society were among the fortunate few.