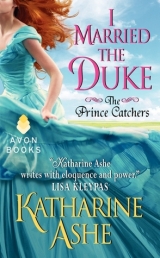

Текст книги "I Married the Duke "

Автор книги: Katharine Ashe

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

She delayed her journey again, and the following week visited the same houses, carrying sweets for the children, honey, and table linens. Mrs. Pickett looked on with disapproval, claiming that farmers did not need fine lace and embroidery. But the farmers’ wives warmed to Arabella, and she no longer needed to guess at their emotions to know their thoughts; they began to tell her.

During the duchess’s long absence from Combe, they said, her brother had come in her stead. On occasion he preached in the parish church.

“You’ve never seen a finer gentleman, milady, or heard such sermons as the bishop’s,” Mrs. Lambkin said, pouring tea into cracked cups. “He talked all about giving to the Lord the best of what He gives us.” Her gaze slipped to her son sweeping the hearthstone. “In thanks, you see,” she added, “so He’ll know we’re not hard-hearted and send us famine again.” Her hands quivered on the pot. The boy’s lean jaw was tight. “We can’t hope to be given bounty when we won’t first give to the Lord, can we now, mum?” Her eyes lifted to Arabella’s briefly then slipped to the burly footman-guard standing just inside the door, then out the window to the other footman leaning against a fence. The woman’s eyes were shadowed with fear.

Arabella tracked down Combe’s land steward at the mill. She made conversation about the estate and he was proud to speak at length about it. But she found could not ask him outright the question she had foolishly never thought to ask her husband; she would not shame herself or Luc in that manner.

At the house, no one had much to say about Christos Westfall. The elder servants remembered him as a beautiful little boy overly fond of drawing and prone to periods of intense thoughtfulness. All assumed that, grown, he had left England for his mother’s country, never to return.

RAVENNA ANNOUNCED THAT she must be off to check on the nannies and their pets before she joined her sisters again in London for the wedding.

“I will send an invitation to your employers,” Arabella said.

“Then they will happily attend. They adore spectacles.”

“I should be leaving as well, Bella,” Eleanor said. “Papa writes that he anticipates my return daily. I will ask him if he will travel to London with me for the wedding.”

“He will no doubt be obliged to remain with his parish. And I am certain he will be unhappy to see you go again.”

“He will.” Eleanor embraced her and kissed her on both cheeks. “But wherever you are, there too I shall be.”

She stood on the drive and waved at the coach that bore her sisters away.

“Joseph,” she said to her guard as she walked into the house. He was a giant of a young man, with arms the size of tree branches and legs like the trunks. “Tell your partner Claude that we will leave for London tomorrow.”

He bowed. “Yes, yer grace.”

CHEROOT SMOKE HUNG thick in the air and men grunted in various stages of inebriation, frustration, and satisfaction as cards passed through hands and bills, trinkets, and vowels passed across the tables. Luc swallowed the last of his whiskey and blinked to clear his vision.

It would not clear. How a man could win a game of anything in this cloud of vice he’d no idea. And how he could bear another night of such excruciatingly dull hedonism without gaining anything for his efforts he was equally at a loss to predict.

He wanted salt air, sea breeze, and a ship deck beneath his feet. Or alternately he wanted country air, wind off the Shropshire hills, and his wife’s body beneath his own.

Actually, scratch the first. The second was all he needed.

But this must be done. Of all the clubs in London, Absalom Fletcher, the Bishop of Barris, exclusively frequented White’s. The last time Luc saw his former guardian he’d said he would cut him into little pieces with a sword and feed the bits to sharks if he could but get him aboard ship, so he thought it prudent to approach him in this subtle manner. Paying a call on him at his house near Richmond probably wouldn’t do. The old duke’s man of business, Firth, had requested a meeting of Combe’s trustees to which Fletcher had not yet responded.

The last had not come as a surprise to Luc. It seemed that the Bishop of Barris employed a one-thumbed coachman. The coincidence with the sailor Mundy’s claim that a one-thumbed man had hired him in Plymouth was too great.

Thus Luc’s current strategy. A skillfully prepared accidental meeting might accomplish what a direct assault never could.

After a fortnight, however, he was beginning to doubt.

“Probably too busy fleecing innocent churchgoers out of their bread money to come out for a game of cards,” Tony muttered, his hand on his hip. The doorman had collected his sword.

Cam strolled into the chamber and wandered over. “Care for a visit to the opera tonight, gentlemen?” he said casually.

“Good God, Charles,” Tony groaned. “All that screeching is enough to send a man back to war, no matter the temptations of the green room. If we must see a show, why not Drury Lane?”

“I have just heard that tonight’s patrons of the opera might be even more interesting than the denizens of the stage or the green room.” Cam lifted a speaking brow at Luc.

Luc threw in his hand and stood. “I am particularly fond of the production tonight. What show is it again, Bedwyr?”

“Hamlet.”

Luc cast him a glance over his shoulder.

“They don’t play Hamlet at the opera house.” Tony followed, weaving a bit. He peered at the doorman who gave him his sword. “Do they?”

“Only the version in which Uncle Claudius employs a coachman who is missing a thumb to murder Hamlet,” Cam said.

Tony screwed up his brow. He turned to Luc abruptly. “Hamlet murders Claudius.”

Luc shot Cam a scowl. “And dies moments later.”

Tony shook his head. “Charles, you rapscallion, there is no version of Hamlet that includes a coachman.”

Luc’s carriage pulled up before the club and they drove to Lycombe House, where he changed his clothes for the opera. Not black for his uncle Theodore, who had allowed the people under his protection to starve, but brilliant blue with a silver and yellow striped waistcoat. Cam’s tailor had clapped in glee when Luc selected the fabrics. He would be the most fashionable man about town in the robin’s egg blue and canary yellow.

Luc could barely look at the avian monstrosity. But if it roused the sober, severely disciplined, and righteous Fletcher’s ire, he would wear a basket over his head and trot up Bond Street braying like an ass.

In point of fact he was an ass. He should not have left Arabella so abruptly. He should have invited her to come to London with him. But he could not protect her when all he wanted to do was ravish her.

Not true. He did want to ravish her. Often. But holding her in his arms during the Channel crossing had been nearly as satisfying. And watching her take tea with the tenant farmers’ wives and listening to her speak with their children and hearing her laugh with her sisters made his chest hurt the way it did when her chin ticked upward with courage. And when she looked at him and her eyes asked questions that made his gut ache and stole his reason, he could not think straight.

Ravishing her was infinitely easier, especially when they didn’t speak.

His hands were clumsy on the neck cloth. Miles tsked and gave him another. He botched that one too.

“If your grace would allow me—”

“I can tie my own damned cravat, Miles,” he growled.

“All evidence to the contrary, your grace. Perhaps a glass of brandy would soothe your grace’s nerves.”

“My grace’s nerves are just fine.” He grappled with the linen. He didn’t need more to drink. He needed a fiery-haired temptress with cornflower eyes hazy in passion, supple raspberry lips, and the softest—

He snapped himself out of fantasy. He’d had to leave her at Combe. With Absalom Fletcher and his one-thumbed coachman in town, she was safest where she could not get caught in the cross fire between him and his would-be assassins.

“This is futile,” he grumbled to his cousin as they took their seats in the box Cam had arranged at the opera house. “I’m wasting my time. Even if I do speak with Fletcher, he is unlikely to confess to hiring men to murder me in France.”

“Too true.” Tony nodded and drew a flask from his uniform pocket. “And I’ll say, these shenanigans are becoming tiresome, Luc. That hideous coat is an absolute travesty. And that little race we enacted in the park yesterday to shock the bystanders left me fifty guineas in the hole.”

“Luc will pay it back to you,” Cam said.

“I wouldn’t have it! He won it fair and square, galloping down Rotten Row like hell was after him.”

“All for show,” Cam said, producing a folded journal page. “It was in the gossip columns today, as hoped. I quote: ‘Are the sporty amusements and defiance of mourning for his uncle merely the fruit of Lord W’s frustration over his continued distance from the ducal title? Or—’ ”

“Idiocy,” Luc scowled.

Cam casually surveyed the theater’s gathering patrons. “But what tack do you propose to take instead, cousin? Break into his house to search his private documents for proof that he tried to kill you?”

“Not a bad idea, though terribly illegal of course.” Tony quaffed from the flask and carefully wiped his moustaches with a kerchief.

“Anthony, you are occasionally a perfect imbecile. It is a wonder the Royal Navy allows you a dinghy.”

“Exceptional service to the king,” Tony pointed to the ribbons and medals pinned across his chest. “Order of the Garter and whatnot.”

“God help our empire,” Cam murmured. “Any word from your brother, Lucien?”

“Nothing. But I have cause to believe he sailed from France a fortnight ago. My man in Calais—” His tongue failed.

From across the theater a slender man with a narrow face and a cloak of black velvet slung dramatically over his black coat, cravat, and knee breeches met Luc’s gaze. He scanned Luc and his eyes narrowed.

Luc’s palms were cold and slick. Streaks of silver swept across Absalom Fletcher’s temples, enhancing the portrait of severe, sophisticated sobriety. But otherwise he looked like the same pious, sanctimonious bastard Luc had last seen a dozen years earlier.

On that occasion he had gone to him demanding to know where Christos had gone. Not yet a bishop but striving diligently by making connections in Parliament and at court, the priest denied having any knowledge of the boy’s whereabouts. He recommended that if Luc found his brother he should return him to his house in Richmond, where Christos would be cared for in a manner suitable to one so prone to hysterical fits.

If Luc had had a sword on him at that moment he would have drawn. Fletcher never admitted to doing wrong, saying that he had cared for them as well as a humble man might, teaching them discipline and the inner strength that they must have to be men of character in the world. Weaponless, instead of murdering him Luc had spat on him.

Then he bought a commission in the navy.

It was the obvious choice. Christos had fled to France, beyond Luc’s protection while the war raged. So Luc had gone to the only place where as a child he had been able to escape Fletcher.

Like Luc’s wife, the Reverend Absalom Fletcher was terrified of open water. And he could not swim.

Now Luc saw nothing of the drama unfolding on the stage below, or the other patrons tittering over his defiance of mourning, or felt anything except the burning in his gut. But at the break in the show he leaned back in his chair as though merely enjoying the company of his companions, and waited.

Fletcher did not make him wait long. Within minutes he made his austere way around the theater to Luc’s box.

“Lucien, what a delightful surprise.” His voice was the same urbane purr that it had been twenty years earlier. A large elegant cross of gold rested on his chest, glittering with tiny diamonds. “Charles.” He flicked a glance at Cam, then at Tony. “Captain.” None of them bowed. Luc silently vowed that if Fletcher lifted his bishop’s purple-gemmed ring to be kissed, he would break every bone in his hand.

He perused Luc’s clothing again.

“You do not wear mourning out of respect for your uncle, I see, Lucien.” His steel gray eyes were stern with censure.

“No doubt because I did not respect him,” Luc could only say. His fists and throat were tight.

“News has come to me of your race in the park yesterday, and of your frequent gaming these past weeks.”

“Has it?”

“Do you care nothing for your aunt’s grief or the honor due your family’s name?”

“I suppose I don’t.”

“It seems you have not changed since you were eighteen, Lucien. It is with great regret that I discover this. I had hoped you would grow to be a man of character, but alas the seeds I attempted to sow in your youth fell on infertile ground.”

Luc couldn’t breathe. “It would seem so.”

“It is a pity. I shall have to counsel my sister to withdraw her support for your trusteeship of the estate during her son’s minority. A duke cannot disport himself as you, and the child must have guardians that teach him well and minister to his lands wisely until he is of age.”

“Since you purchased your way into the episcopate, Fletcher, have you now a direct conduit to God’s ear,” Luc ground out, “so that you already know that my unborn cousin is a boy?”

Not a muscle on the bishop’s face twitched. “I understand that you have wed a woman of the serving class, Lucien.” He shook his head dolefully. “You were never even as intelligent as your brother. As feeble-minded as he was, at least he knew when to behave according to his best interests.”

Luc saw red.

With a glance at Cam, Fletcher left the box.

Tony gripped Luc’s arm, holding him still.

“Gentlemen,” Cam said, “shall we depart? I’ve had enough of the show for this evening and I happen to know a bottle of brandy with our names on it.”

“Two bottles, I hope,” Tony said. “The soprano gave me the most dreadful megrim in the first half. If I’m obliged to suffer through the second half I may go deaf. Then you would have to go mute, Charles, and the three of us could set up a booth at the fair and sell tickets.”

“I will go mute when you do away with that ridiculous sword, Tony.”

“Sword’s been in the family for—”

“Decades. Yes, we know. That doesn’t make it any less vulgar than the day it was forged.”

“Eye of the beholder and all that.”

“Speaking of, aren’t whiskers like yours disallowed in the navy?”

“Got a special privilege, don’t you know.”

“Special privilege?”

“Already told you, Charles: king, Garter, whatnot. You ought to have been there. Ceremony was excellent. Now that was a rollicking good show.”

They were speaking nonsense to cover his silence. Luc was grateful.

HE DID NOT accept Cam’s invitation to drink himself into temporary oblivion, but made his way home. Already in her confinement, Adina was ensconced in a suite of chambers in Lycombe House, surrounded by servants and attended by a companion, and Luc had seen little of her except in initial greeting. The ducal physician reported that the infant was growing as it should, and the duchess was well albeit weak. It was entirely possible, he told Luc in private, that this child might survive. The duchess required rest, however, and not to be bothered by anything other than the most inconsequential matters.

But Luc could not delay speaking to her any longer. As he had hoped, his charade of hedonism had sufficed to draw out Fletcher’s threat: his intention to cut him out of the business of the estate and raising Adina’s son—if it were a son—was clear. Legally the bishop could not remove him as a trustee of Combe; Theodore’s will was inviolate. But Fletcher was the principal trustee and he must hope to gain through it, and he saw Luc as an impediment. Perhaps he imagined that if Luc were out of the way, Christos could be controlled—whether as heir to the child or as the duke himself if the child were a girl. Then Fletcher would control the dukedom.

According to Theodore’s will, Adina now had no legal control over Combe or her child’s future. Given his uncle’s devotion to the beautiful young wife with which his old friend Fletcher had provided him nineteen years earlier, Luc wondered why.

It was time to have an interview with the expectant mother.

When Luc returned to the house, Miles fussed over him like a mother hen. He drew the coat from Luc’s shoulders and held it pinched between forefinger and thumb.

“Burn it. The waistcoat too, and all the other carnival clothing I’ve worn this past fortnight.”

“Thank heaven!” Miles deposited the coat in the corridor. “Then am I to understand, your grace, that you encountered the bishop tonight finally?”

“Yes, but how you know that—” He shook his head. “Bedwyr.”

“His lordship saw fit to inform me of the reason for your atrocious decisions concerning fashion and amusements of late, your grace.”

“I’m sure he did.” He drew on his dressing gown and went to the door.

“The library tonight, your grace? Or will it be the parlor? I have given each a careful survey and I find that the chairs in the library are considerably more comforta—”

“Don’t henpeck, Miles.”

“Forgive me, your grace.”

“I always do.”

“Your grace, I must inform you of—”

“No more tonight, Miles.” He pulled open the door, more exhausted than he’d been since he was lying on a cot recovering from a stab wound to his gut. “I am finished for tonight.”

HE AWOKE IN a cold sweat from a dream of his six-year-old brother riding along the crest of Combe Hill and falling off a cliff that was not there in reality. A woman appeared on the hill, walking steadily upward, her fiery hair catching the sun. Luc called to her but she did not answer. She marched toward the crest.

Arabella’s name was on his lips as his eyes flew open. Daylight peeked through the library curtains.

He reached for the half-finished glass of brandy on the table beside him and swallowed it. Warmth trickled into his chest, but not enough to offset the ache in his side and neck. Miles had clearly never slept in one of the library chairs.

He went to his chambers and dressed in a black coat, black breeches, and black cravat. His uncle, who had never believed the stories Luc told him about Fletcher, did not deserve it, but the Lycombe name and his comtesse did.

Miles minced around him, clearly bursting to speak. But years ago Luc had warned his valet that if he ever uttered a word before breakfast he would discharge him from the Victory’s thirty-two-pound gun into the depths of the ocean.

In the breakfast parlor the servants seemed peculiarly alert. He didn’t know them; they were all Adina’s people and he’d had only a fortnight in the house. But every time he looked up from the paper or his beefsteak he caught them peering at him with bright eyes.

Their attention soured his appetite. He pushed away his plate and went up to Adina’s suite.

Her sitting chamber was rich with gold and yellow to compliment her guinea curls, brimming with satin pillows and lacy fripperies and dainty porcelain gewgaws, and awash in flowery perfume. In the middle of this gluttonous mass of feminine excess—like a lissome ebony candle lit with the purest flame—was his wife.

Chapter 15

Secrets

Arabella arose, smoothed out her black skirts, and fought with the competing desires to throw herself into Luc’s arms like a strumpet or remain coolly aloof like a comtesse. He looked tired, the scar pulling at his right cheek tighter than usual and his tan skin pale. Dissipated, if what she had been hearing from Adina’s companion was true.

When she was not with the duchess, Mrs. Baxter spent her time flitting about from drawing room to drawing room gathering the juiciest on dits. According to that gossip, the new duke had spent a fortnight in town carousing and gaming and getting up to larks, and generally dishonoring the Lycombe name. It was so thoroughly unlike the man Arabella knew, she hadn’t believed it.

He did not, however, appear happy to see her.

He bowed and said graciously, “What a bevy of angelic beauty I have stumbled upon. But perhaps this is not Earth. Perhaps last night I perished in my sleep and I am now in heaven.” His gaze shifted to her and his brow creased.

“Lucien, how lovely of you to come see me,” Adina bubbled, and laid out her hand to be kissed. Luc bowed over it then nodded to Mrs. Baxter. Her lashes fluttered at least twenty times as she drew out the word commmte as though she could not bear to give it too little emphasis.

Arabella was obliged to offer her hand as well. His was warm and strong, and she had missed him so powerfully that now she could feel the life waking up in her again. He brushed his lips to her knuckles and her toes curled.

“Comtesse,” he said.

She curtsied. “My lord.” Her voice did not quaver. A tiny triumph. She could manage this. There were more important things at stake than her foolish, girlish heart that wanted to beg him to love her, or her body that remembered quite tangibly what he had done to it when they had last touched.

He released her and she regained a trace of the composure she had practiced so diligently until meeting Luc Westfall caused her to throw it all to the wind. She knew she should still be angry and hurt and stalwart in defending the walls around her heart. But those walls had long since crumbled. She could only stand atop their ruins and hope the invader was merciful.

“How perfectly delightful,” Adina cooed. “To witness the reunion of a love match.” She sighed, then her sparkling eyes went wide. “Dear me, Arabella, I have not yet asked you how you and Lucien came to fall in love. Your beauty speaks for itself, of course, and we know how gentlemen value that above all other feminine traits, do we not?” She nodded in wisdom. Mrs. Baxter mimicked her.

“You are quite right,” Luc said. “Men are profoundly stupid when it comes to beautiful women.”

Arabella’s heart thumped. He could not mean to be cruel. But his jaw was tight.

“Adina,” he said. “I should like to speak with you at your leisure. After, that is, I enjoy a private moment of reunion with my wife.”

Adina’s smile glowed. “Of course, Lucien,” she said, and waved him toward the door. “Do take this lovely girl away and kiss her soundly. It shan’t be said by anyone that I would stand in the way of lovemaking.” She laughed softly and gaily. Mrs. Baxter giggled.

Arabella felt embarrassed for them both, nearly forty yet behaving as foolishly as fifteen-year-olds. But she was likewise guilty, wishing for kisses from the man who had tied her in knots of infatuation for months, this despite her plan to wed a prince and his careless and dishonest treatment of her.

Luc gestured her before him. In the corridor, Joseph’s straight back jerked even straighter as they passed.

“Cap’n!”

“At ease, Mr. Porter.”

Luc opened another door and again ushered her in. It was a parlor, furnished with an eye for high style and little comfort. She went into the middle of the chamber and did not sit.

He closed the door and came to her until he stood quite close. “I told you I would return to Combe and bring you to London myself.”

She clasped her hands together. “Ah. It seems you have learned the art of my disagreeable greetings.”

He did not smile. “Why did you come?”

“To make plans for the wedding, for which you gave me carte blanche if you recall. And to share with you information that I have learned which could not safely be conveyed in writing.”

His brow dipped. “Information?”

“Adina’s child is not your uncle’s.”

His eye widened. “She told you that?”

“No. I learned it from Mrs. Pickett and had it confirmed by nearly everybody else on the estate.”

“You asked them?”

“Of course I did. I first went to the house servants and inquired as to the true identity of the child in the duchess’s womb. Then I made the rounds of the gardeners and stable hands. And finally I put the question to the tenant—”

His hand jerked forward as though he would take her arm, then it dropped to his side. “How did you learn it?”

“By some very complicated addition and subtraction. I was a governess once, you see, and my arithmetic is especially good. I realize it may seem remarkable to you, a man with some university education, but I can count above the number nine. It is so convenient to possess these little skills sometimes.”

He lifted his hand again, this time to rub at the scar beneath the lock of dark hair that fell over his brow. But Arabella espied a crease in his cheek.

“After you left Combe abruptly without notice or explanation—”

“I wrote you a message.”

“—I busied myself by going about to visit the tenant families—”

“Like the duchess you are well suited to be.”

Butterflies alighted in her stomach. “Everybody was eager to make it clear to me that Adina had not visited the estate since before the famine, and that the old duke was too ill to leave Combe during that time. Luc, they wanted me to know the baby is not Theodore’s.”

“It isn’t proof.”

“What do you mean, it isn’t proof? Hundreds of people are certain of it, the housekeeper inclu—”

“It is Adina’s word against all those people, and Adina’s word will carry the day.” He shook his head. “I am afraid that is simply the way of it in the world of the licentious peerage, little governess.”

She bit the inside of her lip. His gaze dipped to it.

She gathered her courage. “Speaking of licentious, Mrs. Baxter has heard the most astounding gossip concerning you, Lord Bedwyr and Captain Masinter lately.”

“Has she? I wonder what sort.”

“Gaming. Drinking. Carousing.” She paused, her breaths short. “Loose women. You know, the usual.”

“The usual, hm?”

“For some men.” She was suddenly fidgety beneath his intense regard. “I feel like we are standing on the deck of your ship again,” she whispered.

“Because you are experiencing the urgent need to clutch a railing?”

“Because you are looking at me now as you used to do then.” She made an attempt to square her shoulders. “Why?”

“Perhaps because I feel like I did then,” he said in a strange, low voice. “Like a beautiful little mystery wrapped in self-righteous modesty and recklessly brave determination has just landed before me and I don’t know quite what to do with her.”

Her heart blocked her throat. “You could—”

The door opened.

Kiss her.

“My lord? Oh. Pardon me, my lady.” The butler bowed. “Joseph said I would find you here, my lord. Captain Masinter’s carriage has arrived. He awaits you on the street.”

“Thank you, Simpson. I will be down directly.”

The butler withdrew.

“Well, there you have it,” he said easily, the intensity gone from his gaze. “There is apparently more carousing to be had, and at only eleven o’clock in the morning. Ah, the life of a hedonist on the town.” He moved away from her.

“You cannot be serious,” she uttered to his back.

“I am not,” he said, his hand on the door handle, his head bent. “Of course. But I’ve nothing else to say, Arabella. So that shall have to suffice for you.”

Her stomach hollowed out. “It does not. But I don’t suppose I have any choice in the matter. Luc, why did you set guards on me at Combe? Do you not trust me, after all?”

“I trust you,” he said.

“Eleanor thought that you assigned Joseph and Claude to protect me.”

For a moment he was silent. “Did you believe her?”

“I don’t know. From what do I need to be protected?” Her foolish heart and his indifference to it.

“Tonight we will have dinner guests,” he only said. “Nothing inappropriate during mourning. Only a few close friends to announce your arrival in town.”

“I—”

“The housekeeper will see to all the arrangements. You needn’t do anything to prepare for it except dress suitably.” He looked over his shoulder. “Wear your hair down, please.”

“I am in mourning. And a married woman. It would not be seemly—”

“Wear it down, Arabella.” He left.

SHE SPENT SEVERAL hours that afternoon closeted with Adina and Mrs. Baxter, who took to wedding planning with gleeful enthusiasm. Adina’s wan cheeks colored prettily with her excitement. When conversation turned to a debate about which florist would provide the freshest roses in November, and a disputation on how the river would not be especially odiferous in this season so they needn’t arrange for nosegays, Arabella went to dress.

She had dismissed her maid and was sitting at the dressing table considering the expanse of bosom and arm that her ebony gown revealed when Luc entered.

“Ah. The lady at her toilette. A man’s greatest fantasy and nightmare at once.”

She tried to breathe evenly as he approached behind her and she looked at him in the mirror. He wore black well, the kerchief about his brow now a mere extension of his forbidding beauty.

“Nightmare?” she said.

“Feminine decisions, of course. For instance, which jewels to wear.”

“I haven’t any—”

He drew forth a box from his coat and opened it. In the mirror two strings of crimson gems glittered in tiny gold florets. “I thought perhaps since you were accustomed to wearing rubies and gold, this gift would not be rejected.”

“They are beautiful, Luc.”

“I imagined them glimmering from within your hair.” He caressed a neatly confined lock from her brow back to the combs that pulled it away from her face. Then he captured it all in his hand and drew it away from her shoulders. “You do not wear the ring tonight,” he said as though he had not before accused her of infidelity with that ring.

“I . . . No.” Perhaps if she told him, he would not scorn her. But she was afraid. “Thank you. You are generous.”

He set the box on the table, withdrew an earring, and dressed her with it. “A beautiful woman needs no embellishments. But a prideful man may give them to her nevertheless.”

She allowed him to place the other earring on her and she turned her head to watch the gems sparkle in the candlelight. He lifted a hand and stroked her cheek softly, then her neck, then her shoulder. She drew in a steadying breath, her breasts pressing at the edge of her bodice full and round and tender with the echo of his touch. She wanted him to touch her and trust her, and to give her cause to trust him in return.

One of them must begin it.

“Many years ago my sisters and I were told that the rightful master of this ring knows our real parents. We were told that the man is a prince.”