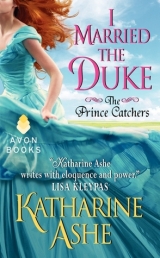

Текст книги "I Married the Duke "

Автор книги: Katharine Ashe

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“I don’t know. I know nothing about the crew of this ship. Or of its master.”

He took a step nearer. “The members of my crew are all men of fine character, Miss Caulfield. The very best, given their lot.” His attention settled upon her mouth. “Considerably better character than mine, I suspect.”

She should not have come out. Her fear aside, she should not have allowed this encounter with him. From the moment at the tavern when he touched her, she had known.

She made herself look directly at his scar. She peered at the puckered slash, angry red against the tan of his skin, and the strip of cloth that covered his eye, and she waited for a shiver of revulsion. None came. His body, so close to hers, seemed to radiate strength and vitality at odds with the disoriented desire in his gaze upon her lips.

Arabella was no stranger to men’s lust. She knew far more about it than she wished. And she knew this man was no longer teasing.

Chapter 3

Brandy

“Will you have your way with me here on deck, Captain? Or can you wait long enough to first drag me by the hair to your cabin? Don’t tell me you are the sort of man to throw a woman over your shoulder.” Her bright eyes challenged, then shifted to run along Luc’s shoulders. “Though I suppose it would barely require an effort.”

It had rarely ever required any effort whatsoever on his part to win a lady’s favors. He was Lucien Andrew Rallis Westfall, decorated commander in His Majesty’s Royal Navy, master of an enviable ship, not to mention a pretty little property in France, and heartbeats away from an English dukedom. Women had begged him to bed them, and wed them.

“From governess to jade in a mere five days.” He forced his feet to remain where they were planted, his hands to remain at his sides. She held the hood of her cloak close about her cheeks. He wanted to see her entire face, to draw away the wool and linen and touch her perfect skin. For five days he had been dreaming of it.

He had avoided her for precisely that reason.

“I had not expected this of you, Miss Caulfield,” he said.

“Then you are indeed foolish, Captain.”

“I have challenged men for offering me less insult.”

“Will it be swords or pistols, then? I haven’t any skill with either, so you may as well choose your favorite.”

A thread of amusement wound through him, and sanity. But with the rain sparkling in her eyes and bathing her skin in ethereal shadows, she was too lovely for him to be content with sanity.

“A man might look without intending to touch,” he said.

“A man might lie through his teeth convincingly if he practices the art of it often enough.” She spoke without bravado, but with warmth and the clearest, sharpest tongue he had ever heard from a woman so young.

“Do you know . . .” He bent his head, hoping to catch her scent of roses and lavender on the breeze. “I have been combing my memory to recall who it is that you remind me of, and I have just come upon it.”

“You have?” The cornflowers widened in a moment of candid surprise.

“In my youth I saw the Duchess of Hammershire. She was an old termagant, sharp-tongued, with an air of sublime confidence and utter indifference to her effect upon others.”

Her lashes flicked up and down once. Her knuckles were white about the railing. His words disconcerted her. Good. The more unsteady he made her, the better. Then they would be on the same footing.

“I am not indifferent to my effect upon others,” she said.

He laughed, and her eyes went wide. “You admit to sharp-tongued and sublimely confident, do you, my little duchess?”

A shiver shook her. “I—I am not your little anything.”

He allowed his gaze to drop to her lips, not raspberry now, but blue. Her quivers were not from fear.

“You are chilled.”

Her chin jutted up. “It is my only recourse to putting you off. I am in your power, recall.” She shivered again.

“I didn’t say chilly. I said chilled. Has the rain soaked you through?”

“I—” Her body trembled beneath the sodden cloak. “That is none of your business.”

“Woman, I have no patience with fools. How long have you been atop?”

“I . . .” Her delicate brow creased, her teeth clicking together.

“Half an hour, Cap’n,” the cabin boy’s voice piped from close by. “Been standin’ there still as a statue gettin’ soaked through.”

“Thank you, Joshua. What are you doing atop at this time of night?”

“Watchin’ the lady, just like you told me to, Cap’n.”

The cornflowers shot Luc a confused glance. Blast the innocent ignorance of children.

“My grandpa took a chill afore he up and croaked in my grandma’s one good bed,” the boy said, and his little jaw dropped open. “Is Miss goin’ to croak too, Cap’n?”

“I don’t believe she would allow that, Josh.”

“You mustn’t—” Her words ended on a hard shudder.

“Joshua, find Dr. Stewart. Bid him attend me in my day cabin.”

“Aye aye, Cap’n.” The boy scampered off.

“Truly, Captain, I shan’t—”

“You shan’t say another word until I say you may.” His hand came around her elbow through the fabric of her cloak. His grip was strong and very tight. “Now do allow me to escort you below, madam.”

She resisted, then released the rail and allowed him to lead her toward the stairway.

Joshua met them at the bottom. “Took me a few to suss him out, Cap’n, this bein’ such a prodigiously grand ship, a’course. But the doc’s on his way now.”

“Excellent.” They passed through the sleeping sailors and came to the cabins. “The lady is in good hands now, Joshua,” he said in a gentle hush. “Off to bed with you.”

“But, Cap’n—”

“If you wish to stand with the helmsman again on the quarterdeck tomorrow and assist him in steering the ship, you will climb into your hammock and go immediately to sleep. No. Not another word from you. Go now.”

The boy hurried into the darkness of the deck.

“Now, little duchess, do follow me.” He opened the door to his cabin.

Another shudder grabbed her and Arabella’s teeth clacked. “Y-You call me d-duchess yet you speak with greater respect to Joshua,” she mumbled.

“He complimented my ship.”

“If I w-waxed eloquent on the prodigious size of y-your . . . ship would you s-speak to me with deference too?”

“Jade. How is it that you can taunt me so indelicately while soaked and frozen? It is truly remarkable.” He pressed her into a chair.

She clutched her arms about her middle and clamped her eyes against a shudder. “I—I did not in-intend indelicacy.”

“Perhaps. I will for the present reserve judgment.” A blanket came over her back. She opened her eyes but, doubled over, she could only see his feet, quite well shod with silver buckles and trouser hems of a remarkably fine fabric.

“Are y-you certain you are not a s-smuggler?”

“Quite certain. Is there something written upon the floor that suggests I am?”

“The quality of your tr-trousers and sh-shoes. Men earned fortunes sm-smuggling during the war ag—” An agonizing shudder wracked her. “—against Napoleon,” she finished in a whisper.

“Did they? I suppose I chose the wrong profession, then. Ah, Dr. Stewart. You are in time to hear all about the fine quality of my footwear. Duchess, here is the sawbones to see to what ails you.”

“Step aside, Captain, an allow a man o’ science to come to the rescue.”

“You n-needn’t rescue m-me, Doctor.” Arabella raised her head and opened her eyes, but everything was a bit spotty. “I am w-well.”

“I can see yer perfectly hale, lass. But Captain, weel, he’s a hard man. He’ll make me walk the plank if I dinna take a look at ye.” He set a chair facing her and sat. “Nou, be a guid lass an’ give me yer hand.”

She unwound her arm from within the wet cloak and he grasped her wrist between his fingers. The captain had moved across the cabin and turned his back on them, but his shoulders were stiff and she thought he listened. Dr. Stewart grasped her chin and studied her eyes. His touch was impersonal, not like the shipmaster’s.

“Shall I bring another lamp, Gavin?” The captain’s voice was gruff, his back still to them.

“No. I’ve seen enough.” The doctor released her and placed his palms on his knees. “Lass, yer chilled through. Ye’ve got to get out o’ those wet clothes and a dash o’ liquid fire in ye or ye’ll take a fever.”

Arabella pressed her arms to her belly. “I have no other c-clothes.”

“Mr. Miles will find something to suit ye.”

The captain looked over his shoulder. “What on earth inspired you to wander atop in the rain and dark, duchess?”

“D-Don’t call me that.”

“ ’Tis no use, lass. He’ll no’ listen once he’s got an idea in his head. Niver has.”

The captain was looking at her, a frown marring his dramatically destroyed face. “He has the right of it. Now, Miss Caulfield, will you allow my steward to dress you in dry clothing and save you from a far worse fate, or will you foolishly destroy the respect I have developed for your courage and fortitude over the short course of our acquaintance?”

He respected her? Hardly.

She nodded and cradled her arms to her.

Dr. Stewart patted her shoulder. “Good, lass.” He stood. “I’ll fetch Mr. Miles. With a dram o’ whiskey in ye, ye’ll be singing in chapel again come Saubeth.” He went out.

The captain sat back on the edge of his writing table, bracing his feet easily against the sway of the ship. He crossed his arms. He had removed his coat and wore now only a shirt and waistcoat. The clean white fabric pulled at his shoulders and arms. There was muscle beneath, quite a lot of it, the contours of which could not be hidden by mere linen. Looking at it, Arabella got an uncomfortably hot feeling inside her. It seemed to split up her insides, jolting against the cold.

She looked away from the muscles.

“I’ll wager you sing in church on Sundays, don’t you, duchess?”

“I d-don’t believe in G-God any longer.”

“That miserable, are you?”

She did not reply. She mustn’t care what he thought of her. The less he thought of her, the less likely he would be to worry about her and stand around her with his indecently oversized muscles.

The cabin door opened and the captain’s steward entered with an armful of clothing.

“Would the lady prefer to dress herself or to be dressed?” he said primly.

Grabbing the blanket about her, Arabella stood and took the clothing from him and went into the captain’s bedchamber on shaking legs.

Impotent frustration rattled in her while she peeled off all but her shift and wrapped her hair in the dry neck cloth in the pile of clothes. But she could not bring herself to don the sailor’s garb. She left it folded, bundled the blanket about her tightly and returned to the day cabin.

Mr. Miles greeted her on the other side of the door with an eager step. “I will be most happy to see to your garments, miss.”

She clutched her clothing to her. “Th-That will not—”

“Accept gracefully, Miss Caulfield,” the captain said in a low voice. “Or I shan’t be responsible for the pall his foul humor will subsequently cast over this entire ship.”

She offered the steward her wet gown and petticoat, with the stays and stockings tucked inside. “I will return with tea for your guest, Captain.” The steward marched to the day cabin door and closed it behind him, leaving her alone at night wearing only a chemise and blanket with the man she had been avoiding for five days so that she would not feel precisely this: weak and out of control.

She stepped back and bumped into a chair. He tilted his head, then gestured for her to sit.

She sat. Better than falling over.

“I continually disappoint Miles in offering him little of variety in my clothing,” he said. “The opportunity to manage yours has put him in alt.”

“He doesn’t c-care for that g-gown,” she mumbled.

“Did he tell you so? The knave.”

“N-Not in so many words.”

“Nevertheless, for offending you I shall have him strapped to the yardarm for a thorough lashing.”

“Y-You won’t.”

“I won’t, it’s true. How do you know that?”

She did not know how she knew, except that despite his arrogance and teasing, he could be solicitous and generous.

“Where is D-Doctor Stewart?”

“He’ll return.” He seemed to watch her steadily. She had often felt invaded by men’s predatory stares, but never caressed.

Now she felt caressed.

Which was impossible and foolish and proved that she was delirious. A shiver caught her hard and she jammed the blanket closer around her.

He went to a cupboard attached to the rear wall of the cabin, drew a key from his pocket, and unlocked the door. Out of it he pulled a bottle shaped like a large onion, with a broad base and a narrow neck, and two small glass tumblers, then moved before her and sat in the chair that Dr. Stewart had vacated. His legs were longer than the Scotsman’s and his knees brushed her thigh, but she could not care. She told herself she did not care.

He set the glasses on the table and uncorked the bottle.

“What are you d-doing?” she said.

With what seemed extraordinary care he filled one glass then the other, took up a tumbler and lifted it high.

“To your imminent comfort, duchess.” He emptied the glass in a swallow. He nodded. “Now it is your turn.”

When she did nothing, he reached forward, his fingertips sliding over her thigh. She flinched.

He grasped her hand and the blanket gaped open. She snatched it back. His brow lifted. But he said nothing about her dishabille, only reached again for her hand and pried her fingers loose from the blanket.

“I am not trying to take advantage of you, if that is what worries you,” he said in a conversational tone, and wrapped her palm around the tumbler. “Dr. Stewart will return shortly with possets and pills and what have you, and Mr. Miles with tea. But while Gavin might not quail, if Miles found me in the process of ravishing a drunken woman he would serve notice, and then where would I be? It is remarkably difficult to find an excellent cabin steward, you know.” He pressed the glass toward her mouth, his hand large and warm about her shaking fingers. “Barring a fire, which I am loath to light aboard my ship, this is the only route to warming your blood swiftly. One of two routes, that is, but we have just established that the other is not an option.”

“Cap—”

“Now, drink.”

Her outrage could not compete with her misery or the heat of his hand around hers. Liquor fumes curled up her nostrils. She coughed. “Wh-What is it?”

“Brandy. I regret that we are all out of champagne. But this will do the trick much quicker in any case.”

She peered into the glass. “I’ve n-never—”

“Yes, I know, you’ve never drunk spirits before.” He tilted her hand up, pressing the edge of the glass against her frozen lips. “Tell me another bedtime story, little governess wearing a king’s ransom around your neck.”

She did not bother correcting him. She drank. The brandy scalded her throat, and the base of her tongue crimped. But when the warmth spread through her chest she understood.

He released her hand and watched her take another sip. She coughed again and her eyes watered.

“You needn’t drink it all in one swill,” he murmured.

“I told you I haven’t drunk b-brandy before.”

“So you say.”

“C-Captain, if you—”

“How do you feel? Any warmer?”

“Why m-must you always interrupt m-me?”

“We haven’t spoken enough for an ‘always’ to exist yet. You have done all in your power not to come within twenty feet of me since you boarded my ship and refused my bed.”

Her gaze shot from the glass to his face.

He lifted a brow. “True?”

“N-No.”

She didn’t think he believed her.

“Now another,” he said, sliding the bottle across the table toward her.

“I will b-become intoxicated if I h-have another.” Her head was muddled already. But she was warm. Warmer than she’d been in days. She feared it had less to do with the brandy than with the man’s quietly wolfish gaze upon her.

He leaned back in the chair, his long legs stretching out to one side of her, trapping her against the table. He folded his arms over his chest. “What are you afraid of, duchess? That under the influence of alcohol you will abandon your haughty airs and do something we will both regret in the morning?”

Men had attempted to cajole her, to seduce her, to make love to her with words so that she would succumb to them. They had treated her to endless flatteries, and when that had not sufficed they had forced her. No man had ever spoken to her like this, so frankly. And no man had ever made her want to do something she would regret in the morning.

But his words now were not meant to seduce.

“You are ch-challenging me, aren’t you?” she said. “T-Testing my m-mettle, like you would test any sailor aboard your ship.”

“Do you wish to be a sailor now, Miss Caulfield? Trade in the dreary life of a governess for adventure on the high seas? I suppose I could arrange that.”

She set her glass on the table beside the bottle. “F-Fill it.”

He chuckled. She liked the sound of it. When he looked at her with amusement, she imagined he actually found her amusing.

She was not amusing. She was serious, professional, determined, and responsible. Except for boarding a ruffian’s ship and sitting before him wearing a blanket, she’d done nothing especially adventuresome since she could remember.

She lifted the glass to her lips. “I am n-not afraid of anything. Especially not of m-men.”

“I begin to believe it.” A smile lurked at the corner of his beautiful mouth. The cabin was a haze of mellow woods and salt-smelling air and heat growing inside her. She could not seem to look away from his mouth. It was not in fact wise to sit before him wearing only a blanket.

“This is u-unwise,” she heard herself say.

“Medicine is rarely easy to swallow.” His voice seemed a bit rough.

She dragged her attention to her glass.

“Why do you cover your hair?” he said abruptly.

“Because I do n-not wish it to be seen by rapacious s-sea captains.” She took another sip of brandy. “Next question.”

He laughed. She did not like it. She loved it—warm, rich, and confident. His laughter burrowed into her, into someplace deeply buried.

“What thoughts had you so lost in bemusement atop that you did not notice even the rain, duchess?”

“I have t-two sisters.” She could not tell him of her fear. “I have not seen them in an age. I m-miss them.”

“Tell me about them.” The golden lamplight cast his features in light and shadows so that he did look mythical. It was not her imagination or the brandy. It was him.

“Why?”

“I have a brother.” He gestured to the framed drawing on the wall. “Common interest. And, given your earlier refusal of my bed, we’ve nothing better to do tonight.”

“D-Do you speak to all women in this manner?”

“Only governesses wearing little more than a blanket.”

“Do you come across th-those often?”

“Never before.”

Over the rim of the glass she met his gaze. The brandy rushed down her throat. She sputtered.

He reached into his pocket and withdrew a neatly pressed white kerchief. He set it on the table between them. She took it up and dabbed at her watering eyes, studying the charcoal drawing. The boy’s eyes were shadowed sockets of fear, his shoulders hunched, the lines of his face severe. Yet the skill of the artist had brought forth his natural beauty, despite the darkness.

“That p-picture is of your brother?”

“A self-portrait.”

“At s-such a young age he is an artist?”

“He is now six-and-twenty. He drew that from memory. Now tell me of your sisters.”

She set down the handkerchief. “Eleanor is g-good and fair, with golden hair and golden-green eyes, and t-tall and slender like a Greek m-maiden of old.”

“Athena, warrior goddess.”

“Wise, but not a warrior. She would rather read than ride or walk or do j-just about anything else. She spends her days tr-translating texts for the Rev– for our father from Latin into English. No one knows. Others th-think it is his work. When I asked her once if she m-minded, she said she preferred it.”

“She is modest.”

“Perhaps.”

He leaned forward to refill her glass, and she smelled clean sea and warmth upon him. What would it be like to be held in his muscular arms?

She must be drunk already.

She had been grabbed, groped, clutched. She had never been held by a man.

He poured brandy into his glass and set the bottle on the table. “And your other sister?”

“Ravenna is a Gypsy.”

The glass halted halfway to his mouth.

Arabella chewed the inside of her lip. “Dark eyes. D-Dark hair. Cannot be indoors. Cannot b-be still. Cannot be quelled.”

“That last is like her sister, it seems.” He drank the contents of his glass in one swallow.

“I am responsible for them.” The words tumbled from her tongue in a rush.

He refilled the glasses. “You?”

“It is why this p-position I go to now is so important. I must . . .” His glass was empty again. She swung her gaze up to him. “Why are you dr-drinking too? You are not chilled.”

“A gentleman never allows a lady to drink alone.” He held the glass in the palm of his hand with ease. Except he was not at ease. Tension seemed to set his shoulders, and his jaw was hard with restraint.

Restraint?

“You are not a g-gentleman. Are you?” she said. “You did not seem so when you denied my request for passage in Plymouth.”

“Which I then recanted.”

“And teased me about your b-bed.”

“A show of gracious generosity on my part.”

“Not just now.”

“That was to put you at ease.”

“What sort of women d-do you usually speak with so that you could imagine that would have put me at ease?”

His eye hooded. “I am a sailor, Miss Caulfield.”

Oh.

But . . . champagne? And his clothing . . . it was very fine. Handsome. He looked like a gentleman, except for the scar and black kerchief and shadow of whiskers on his jaw and wolfish glimmer in his eye and havoc he was wreaking with her insides.

She wasn’t thinking straight.

“Gentlemen tr-treat ladies better,” she said.

“So I hear.”

“Some gentlemen.”

He leaned forward, his knees coming around hers. “Not all?”

“Not . . . most.” She lifted her attention from their knees locked together.

Hungry.

His gaze upon her was hungry. Like the wolf looking upon the lamb.

He stood abruptly, the chair scraping back, and swiped his hand around the back of his neck. “Not this one, apparently.”

She got to her feet and the blanket drooped open. But she was warm finally. Her teeth clacked but deep inside her swirled heady heat. The lamplight threw his good eye into shadow, but she saw the confused desire there. He was both unsteady and authoritarian and he looked at her like no man ever had before, like he wanted her but did not understand that he did.

“I think you should go to bed, Miss Caulfield.” His voice was low. “Now.”

She could not think. The brandy stole her reason. Her head spun. Dr. Stewart was right: she was intrigued. More than that. She was infatuated. Upon so brief an acquaintance. Like a schoolgirl. Like the schoolgirl she had never really been because even then she had been serious, learning to be a lady despite all. When the other girls at school nursed tendres for the dancing master, she did not. She had remained directed and determined, waiting for a prince to come along and tell her the destiny that was just out of her grasp.

Now, with only two glasses of spirits, a piratical shipmaster threw her into foolish infatuation.

It was ridiculous.

She must halt it before it got out of hand.

“Why d-did you order Joshua to follow me about ship?” She said it like an accusation.

“So that I would know where you are.”

“D-Doctor Stewart s-said—”

“What did he say?” He stood so close she could feel the heat from his body.

She was having difficulty breathing. “He said I would not be the first.”

The door swung open. “Captain, I have hung the lady’s garments in the warmest location aboard. Shall I make up the bed?”

The captain stepped back from her and nodded, turning his head away. “Do.”

His steward went to the little cabin off the captain’s day cabin. A dart of panic shot through Arabella. On wobbly knees she moved toward the door.

“No escaping, duchess.” The captain stepped forward and swept her up into his arms. “Not this time.” He carried her into his bedchamber. To his bed. She could not catch breath. His arms gave her no quarter. Thrillingly muscular arms. And hard chest. She was touching his chest. A man was carrying her to his bed, a man with desire in his eyes who smelled of salt and sea and heat and power, and she was frightened because the drunken part of her wanted him to carry her.

“No.” She struggled. “You must n—”

He dropped her onto the mattress and backed out the door. “Rest well, duchess.” He disappeared.

She pressed her burning face into the pillow while Mr. Miles tucked the blankets around her and made clucking sounds like a nurse settling an infant into a cradle.

“Dr. Stewart will be in within an hour to see that you haven’t taken a fever,” he said. He left. No key sounded in the door, nothing trapping her except the softest mattress she’d slept on in years and a cocoon of warmth bearing her into sleep.

HE SHOULD NOT have drunk a drop. He should have remained sober so that when the magnificent cornflowers grew hazy then wild then caressed him like a touch, he would not have started imagining peeling the blanket off her to reveal the woman beneath.

With nothing to conceal it, the ruby ring had dangled from its modest ribbon where the blanket gaped at her breast as though it weren’t worth five hundred guineas and she had no cause to hide it. Only the sight of that ring, and some remnant of gentlemanly honor his father and the Royal Navy had drummed into him, had restrained him from doing as he imagined.

She claimed she did not belong to any man. Except for her saucy tongue, she responded to his decidedly ungentlemanly teasing as predictably as any virginal governess.

But that ring told another story. Unlike his rakish cousin the Earl of Bedwyr, however, Luc preferred his women unentangled. Also, not shivering. Or tinged blue.

He climbed the companionway to the main deck. The rain had let up while he’d been below fantasizing about undressing a woman while she sat before him. Wind sheared off the ocean to port cold and fresh. Within two days they would make harbor at Saint-Nazaire and his passenger would set off toward the castle, his castle to which he himself had not been in many months but where his brother, Christos, and his friend, Reiner of Sensaire, were now in residence.

She was going to his house—his chateau that had come to him from his mother’s family, the mother who abandoned her young sons upon the sudden death of her husband, to then cast herself into the hands of revolutionaries in her home country. Now, a beautiful little English governess had sought him out to take her there so she could work for his friend.

What were the odds? Luc wasn’t much of a wagering man, but he suspected they were pretty damn slim.

The sea spread out around him, and the solid boards of his ship and the bleached sails above were peace. With a turn of his head he could see in every direction. He passed the remainder of the night as he usually did, watching the stars. Though he would have liked his hands around the ship’s wheel, he had drunk too much brandy, and while seven months ago that wouldn’t have much affected his ability to steer his vessel, he wasn’t so much of a fool that he believed he could steer both foxed and one-eyed.

A pirate. He laughed. The One-Eyed Captain they would have called him if he had remained in the navy. Now when he returned to London he would be the One-Eyed Heir. And someday, perhaps, the One-Eyed Duke.

That one-eyed duke would require an heir.

He tried to imagine the society debutantes he had been introduced to in his youth before he escaped to war. The only face he could conjure was hers. Even pale and shivering, she was stunning. And she was not as disinterested in the company of a man as she said. Brandy had revealed a longing in her eyes that had gone straight to his groin.

He didn’t need that sort of trouble. There would be women to spare in Saint-Nazaire who could satisfy his needs quite satisfactorily.

If he could endure two more days of not touching her.

Her hair bound up beneath that linen was driving him mad. Each time he’d glimpsed her across deck he nearly ordered her locked in the bilge so he wouldn’t be tempted to accost her and strip that damn turban off. She had to know that binding any part of her tightly away from sight made her all the more tempting. Especially that hair.

It was glorious. Golden-red. The linen had slipped while she drank his brandy, and a crest of luxurious color showed above her brow. Like spun copper. He’d drunk with her to avoid snatching that turban away and seeing all of it. Then he had thrown her into his bed, despite her protests. That he had removed himself from the bedchamber was a miracle he was still too foxed to fathom.

He reached up and pressed his fingertips into his right eye. A spark flashed, a tiny thread of lightning across the black, like his memories, fleeting yet devastating.

As the first stirrings of gray crept onto the horizon, Luc got to his feet and—carefully, as he did everything now—made his way to the companionway and below. The dawn crew had stowed their hammocks, and sailors cupped tins of tea and biscuits in their palms. They nodded. A few nostalgic fools even saluted as he walked by and entered his cabin. He drew open the door to his bedchamber.

In a chair propped against the wall, Gavin came awake with a start. He shook his head free of slumber. “How much brandy did ye give her, lad? She’s been out cold the nicht.”

Luc cupped his palm around the back of his stiff neck, remembering her distress at the tavern in Plymouth, knowing her sleeplessness on board. “I think it is entirely possible that she hadn’t slept in days before this.”

“Aye.” Gavin nodded. “So ye put her to sleep.”

“It seemed the swiftest solution.”

Gavin took up his satchel and patted Luc on the shoulder. It was a familiar gesture, banal, and yet Luc felt the affection as though it were the wool blanket that cocooned the woman in his bed.

“She’s no taken fever. Ye’ve done guid, lad. As ye always do.”

He stepped back to allow Gavin through the door. Then he entered his bed cabin and sought out her form in the dimness. Miles—the old mother hen—had wrapped her in his own favorite blue wool blanket and tucked it around her neck. Her breaths were deep, her mouth open slightly.