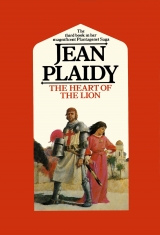

Текст книги "The Heart of the Lion "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

‘And certain friendships are good to have.’ He could almost hear Philip speaking.

Why had he allowed Philip to go on to Acre without him? What when they met there? He could picture the sly smiling eyes of the King of France.

‘And your marriage, Richard, how was it?’

And all the time Philip would know full well that there had rarely been a more reluctant bridegroom than the King of England.

He slept at last. Day had broken when he awoke. There were noises outside his tent, the sound of excited chattering voices.

He dressed hastily and went out to see what was the cause of the excitement.

No sooner had he appeared than several of his knights came hurrying to him.

‘Three galleys have just come into sight, Sire. Look. You can see them . . . out there on the horizon.’

Richard could see them.

‘By God’s eyes,’ he cried, ‘whose can they be?’

For the moment he had felt a wild excitement, for he had thought that they might well be Philip’s. The storms which had beset him would have worried the French fleet and the French were not as good sailors as the English. They lacked that passion for the sea which most Englishmen felt, and preferred to travel by land when possible.

But it was clear that they were not French ships.

‘I myself will go out and see who comes into Cyprus,’ said Richard.

His friends began to dissuade him but he waved them aside. He wanted to know who the visitors were and was too impatient to wait on shore while someone else was sent out to discover.

He was rowed out to the galleys, taking his trumpet with him.

When he approached the first of the galleys, he shouted through the trumpet: ‘Who is this who comes to the Island of Cyprus?’

Someone was standing on the deck shouting back.

‘This galley belongs to the King of Jerusalem.’

The King of Jerusalem! thought Richard. Alas, it was now an empty title. But he guessed that this was Guy de Lusignan who had been deposed when the Saracen armies had captured Jerusalem. Saladin now reigned in the place which had once been Guy’s.

‘And what do you here?’

‘I come seeking the King of England.’

‘Then your search is ended,’ replied Richard. ‘The King of England is here before you.’

‘Praise be to God. Will you come aboard?’

‘Aye, I will,’ said Richard.

When he stood on the deck, Guy de Lusignan knelt and kissed his hand.

‘The Lord is with me at last,’ he said. ‘I knew that you were on your way to Acre and I hoped to intercept you.’

‘You have come from Acre?’ said Richard.

‘I have. The French King is already there.’

‘Has he made many conquests?’ asked Richard jealously.

‘Nay, he is no great soldier. But he is a great schemer as I know to my cost.’

‘How is that?’ asked Richard.

‘He works against me.’

‘How can that be? His aim is to take the crown from Saladin and restore it to a Christian king.’

‘A Christian king, my lord, but he has chosen his own man, whom he will support. If we regain the Holy City . . . when we regain the Holy City he will nominate Conrad de Montferrat as King in my place.’

‘Why so?’

‘Because Montferrat would be his man.’

‘Philip is a statesman. He thinks always of the advantage to France.’

‘He has shown himself to be my enemy. I have come to you. I wish to put my services at your command. If you will support my claim I would snap my fingers at the King of France.’

Richard said slowly: ‘My friend, we must talk of these matters.’

He did, but his main preoccupation now must be his wedding, never forgetting of course that Isaac had been driven back only a few miles and could at any time muster his forces for an attack. Nevertheless the people of the island were clearly friendly and the prospect of a royal wedding delighted them. Such was Richard’s personality that although he had come to their island a short while before and was now installed as a conqueror they were ready to accept him and share in his wedding celebrations.

His own chaplain Nicholas was to perform the ceremony and Richard smiled grimly to think how chagrined the Archbishop of Canterbury was going to be because it was a prerogative of that Archbishop to officiate at the weddings of England’s Kings. It was certainly going to be an unconventional wedding.

Still, the circumstances were such as made that necessary, and although Richard would have been prepared to postpone the wedding until his return to England he realised that was quite out of the question.

In their apartments Joanna helped prepare Berengaria for her wedding. She was a beautiful bride. Her long hair was parted in the centre and fell on either side of her face; a transparent veil covered the hair and this veil was held in place by a jewelled diadem. She looked serene and happy and even more than usually elegant in her long clinging white gown.

Joanna studied her with pleasure. What a relief that the marriage was at last going to take place! Surely nothing could happen to prevent it now. Would Isaac Comnenus decide to attack while the ceremony was in progress? No, he was in no position to attack. He had been driven away and Richard was so confident that he had been beaten that he was considering having himself crowned King of Cyprus. He had the people with him and now Guy de Lusignan had come with his three galleys full of men to support him. No, Isaac would not be so foolish and the marriage must go through without a hitch.

‘You are happy, Berengaria?’ said Joanna.

There was no need for Berengaria to answer that. ‘Richard is so wonderful,’ she said. ‘I never cease to marvel that I should be his chosen bride. From the moment I first saw him when he came to my father’s court I loved him. I had never seen such a handsome, such a chivalrous knight. And then . . .’

‘You waited,’ said Joanna. ‘You waited a long time for him, Berengaria.’

‘But the waiting is over now.’

‘May you be very happy,’ said Joanna fervently.

‘I shall. I know I shall.’

‘Amen,’ whispered Joanna.

‘Joanna, I wonder what Alice is doing now. I wonder what she will think when she hears . . .’

‘She will be going back to her brother’s court now I doubt not.’

‘Poor Alice!’

‘Do not pity her too much, Berengaria. Perhaps she was happy while the King lived.’

‘But the shame of it!’

‘Perhaps she did not feel the shame.’

‘How could she not when it was there?’

‘It may not have seemed so to her.’

‘Oh, but it must have, Joanna.’

Joanna thought: How innocent she is! May all go well with her.

She wondered whether she had heard the whisperings about Richard and whether she would have understood them if she had.

When Richard rode out to his wedding the people stared in astonishment at this splendid figure.

This was to be a double celebration. First the wedding and then the coronation for he had decided to have himself crowned King of Cyprus. The island was rich; its people were dissatisfied with Isaac Comnenus and he, Richard, was in a position to defeat Isaac utterly. What treasure would be his! He could install a deputy of his own choosing to hold the island for him when he went on his way to the Holy War. He had done very well in Sicily but he would do even better in Cyprus.

Because this was his intention he had exploited to the full that which he knew to be one of his major assets – his dazzling appearance. He appeared as a god and was accepted as such; his height and fair good looks gave all that was necessary to add to the illusion. So he rode out in a rose-coloured tunic, belted about the waist. His mantle was dazzling, being of silver tissue patterned with stripes and decorated with half moons of silver brocade. His head-dress was scarlet decorated in gold. He shone; he glittered; he was indeed like a being from another world.

He did not ride but walked to the church, his Spanish horse being led before him by one of his knights also splendidly garbed though of course in a fashion not to be compared with that of the King. The horse’s saddle was decorated with precious stones and gold, and never before had the Cypriots seen such glory.

And in the church he was married to Berengaria. She felt exultant, for this was like a dream coming true – a dream that had haunted her since she had seen this perfect knight ride into the joust with her favour in his helmet.

Not only was she Richard’s wife, she was also Queen of England and Cyprus, and the heavy crown that was placed on her head when the diadem was removed was a double crown.

How the people cheered them – not only the crusaders but the islanders.

With Richard she sat at the table and the feasting began. There was merrymaking, songs and dancing; and Richard himself played his lute and sang a song of his own composing.

This, thought Berengaria, is the happiest day of my life.

When night fell he conducted her to their bedchamber. He was not an ardent lover but she did not know this. To her he was the most perfect being the world had ever known and she was in a state of bliss because fate had made her his bride.

The day after the wedding, messengers came from Isaac. He craved a meeting with the King of England and their meeting place should be in a field near Limassol. He wanted to treat for peace.

Richard was eager for the meeting too and it was arranged.

Donning his wedding finery Richard rode out to the field and when he reached it he saw that on the far side Isaac waited with a company of men.

Richard dismounted and his magnificent Spanish steed was led before him as it had been when he was on his way to the church for his wedding. He had never looked so glitteringly godlike and formidable. At his side hung his tempered steel sword and he carried a truncheon. He came as the conqueror and Isaac quailed before him.

Isaac knelt and Richard inclined his head.

‘You sue for peace,’ said Richard. ‘That is well but I shall expect recompense for what you have taken from my men.’

‘I shall be happy to give it, my lord,’ said Isaac humbly.

‘My men have been shipwrecked and their goods taken from them. Many have suffered imprisonment.’

‘’Tis true, I fear, my lord.’

‘These wanton acts deserve punishment.’

Isaac studied the King. There was an innate honesty in those blue eyes. The King of England it was said was very different from the King of France. Richard was direct – Yea and Nay, they called him, and that meant that when he said something he meant just that. There was no subterfuge about him. In a king this could be naïve, and Isaac was far from naïve. He was in a difficult position. He had made a great mistake when he had allowed his people to plunder Richard’s ships. He should have welcomed them, curried favour with Richard; but how was he to have known that Richard would arrive in Cyprus? He might so easily have been drowned. He should have waited though and made sure.

Now here was Richard, the legend, the unconquered hero. One only had to look at him to see that he was a dangerous man to cross.

Thus it seemed to Isaac that there was only one course open to him. He must be humble, never forgetting that the weakness in Richard’s armour was his inability to dissemble; his knowledge of warfare was great but his understanding of people non-existent. He made the great mistake, characteristic of his kind, in thinking everyone reacted and behaved as he did.

‘Alas, my lord,’ he said, ‘my people have sinned against you and I must take responsibility for their acts.’

‘You yourself have shown me no friendship.’

‘For that I am at fault.’

‘Then we are of one mind. As I said I shall need reparations.’

‘That is to be expected. I will pay you twenty thousand marks in gold as recompense for the goods which were taken from the shipwrecks.’

‘That is well but not all,’ said Richard.

‘I have thought a great deal about your mission to the Holy Land. I shall pray for your success.’

‘I need more than your prayers, Isaac. This is a costly enterprise.’

‘The twenty thousand marks will doubtless be of use to you.’

‘They will, but I need men. You must come with me. I doubt not your sins are heavy and you are rich . . . or you were until you fought against me and my holy project. This will be a lesson to you, Isaac. Not only did you work against me but against God. You must ask forgiveness for your sins and the only manner in which you can do this is by joining my army.’

‘My lord, I have my island . . .’

‘Nay, Isaac. You no longer have an island. I have been crowned King of Cyprus and your people were very willing that it should be so. You will join my company and bring with you one hundred knights, four hundred cavalry and five hundred armed footmen.’

‘I have not these men.’

‘You can find them. You will find them. For these services I will appoint you the Lord of Cyprus, my vassal ruler. You will rule Cyprus in my name. If you do not agree to these terms you have lost Cyprus for ever.’

‘But if I am to rule in your place how can I do this if I am fighting in the Holy Land?’

‘You will name a deputy. He will rule under you who in your turn rule under me. I have had to appoint deputies to rule for me in England.’

‘I see that it must be so,’ said Isaac. Then realising that it was no use pleading with Richard and that the King believed that if he had made a promise he meant to keep it he began to talk enthusiastically of what he would take with him on his journey to the Holy Land.

Richard said: ‘You have a daughter.’

‘My only child,’ answered Isaac. ‘She is very young.’

‘And your heiress.’

‘I fear to leave her,’ began Isaac.

‘She must be placed in my care,’ said Richard. ‘I will see that no harm comes to her and when the time is ripe arrange a good marriage for her.’

Isaac bowed his head. ‘I know that I can trust my child with you,’ he said.

‘I think we have settled everything,’ answered Richard.

Even he, however, was not entirely sure of Isaac. He told him he would have him lodged within the English lines and make sure that he was treated according to his rank.

Isaac thanked him for his consideration.

‘It makes me happy,’ he said fervently, ‘that you and I are no longer enemies.’

Richard lay beside Berengaria in the silken tent which was part of the spoils he had taken from Isaac. He looked at her innocent face and felt suddenly tender towards her. He could be fond of her for she was gentle and undemanding. He supposed that, since he must have a wife, he could not have a better one.

He thought of Philip and his Isabella. Philip had his son, young Louis, and was proud of the boy. Perhaps he would be proud of a boy, if there was one.

There was nothing now to keep him in Cyprus and he could think of leaving very soon. Now that Isaac had made his terms and was ready to accompany him, he could be pleased with the manner in which everything was going. It was mid May – a long time since he had left England, but his mother might well be there by now and he need have no qualms for his realm. She would keep him informed of what was happening. And soon he would be at Acre. He would be with Philip. Together they would storm the place as they had always planned to. He would arrive richer than he had set out for he had treasure from Sicily and more from Cyprus. He had added another crown to that of England. It had been worth the delay.

Berengaria stirred and his attention was drawn back to her. He had forgotten her in his contemplation of the battle to come.

She would always be there in his life to come; he would have to think of her occasionally. It had been less onerous than he had feared it would. He could accept Berengaria. She need not take up too much of his time and he would do his duty now and then; they would have sons and his mother and the people would be satisfied.

He rose and left his tent. It was early morning yet but he liked to be astir soon after dawn. He wanted to get on with his plans for departure for the weather was favourable and there was now no longer any reason why he should delay.

He would go to Isaac’s tent and awaken him. He wanted to talk to him about an early departure. He felt sure that Isaac had little knowledge of what equipment he would need.

He noticed that there was a deserted air about that part of the camp in which Isaac and his followers had been lodged so he went into Isaac’s tent. It was empty.

While he stood looking around he saw that Isaac had left a message for him.

Isaac had gone, the note told him. Surely Richard did not imagine that he could agree to the harsh terms that had been imposed. He had in any case changed his mind and was determined that he would keep no peace nor enter into any agreement with the English King.

Richard’s fury was great. He had been deceived. Isaac was no doubt laughing at him now, but he would not laugh for long.

There was no time now for wedding celebrations.

Richard marched across the island towards the capital Nicosia. He found the Greek style of fighting strange and it was not easy at first to adjust himself to it. They did not face him and fight; they sniped at the flanks of the army, and having shot their arrows fled. As he had led his army he could not at first see the enemy so he immediately placed himself at the rear where he could more easily detect the marauding bands and whenever he caught sight of them prepared to charge.

It was unsatisfactory but in a way exhilarating as any new techniques in fighting must be to him.

At one time he caught sight of Isaac. A small party of Greeks had come up from behind and suddenly becoming aware of them Richard had turned to see Isaac himself but a short distance away. Before he could act Isaac had shot two arrows at him. They missed by inches . . . poisoned arrows which would most certainly have killed him. Exhilarated to be so near his enemy Richard immediately gave chase, but Isaac’s steed was especially fleet and he got away.

A horse made for running away, commented Richard, but he was a little shaken that the enemy had been able to creep up on him in such a manner.

He hurried on to Nicosia, the inhabitants of which surrendered immediately.

This was victory. When his capital fell to Richard, Isaac must realise he was defeated. In fact only a fool would have attempted to hold out against such a superior foe.

There was one thing which was troubling Richard. When he had started his advance he had felt the first signs of fever. It may well have been due to this that Isaac had almost succeeded in killing him with his poisoned arrows, for had he been as alert as he usually was, he would have been more prepared.

He trusted that he was not going to have one of the old bouts of fever, but as the days passed it became more and more certain that this was exactly what was going to happen.

To be ill at such a time could be disastrous.

He asked Guy de Lusignan to come to his camp. There was something about the young man that he liked. His nature seemed to be as frank and open as that of Richard himself, and the King felt that they were two of a kind.

Guy looked at him with real concern.

‘Why, Sire, what ails you?’ he asked.

‘I fear it is a return of an old complaint.’

‘You are often ill like this then?’

Richard laughed grimly. ‘I know it seems incredible, but this fever has dogged me for years. It started through sleeping on damp earth when I was quite young. You know how it is. One is careless. One fancies one is above the common ailments of the body. Alas, it is not so.’

‘Will it soon pass?’

‘I doubt not it will be worse before it is better. That is why I have asked you to come to me. In a day I may not be able to leave my bed. The fever will run its course. I want you to take over command of the army.’

Guy was astounded. He could not believe that the man on the bed, his face pallid, cold sweat on his brow was the great and glorious warrior who such a short time ago had been married to the Princess Berengaria.

Guy said: ‘Should not the Queen be told? She will wish to look after you.’

‘Neither Queen must be told – my wife nor my sister. I do not wish them to pamper me as though I am a woman. I know this fever well. It comes and it goes. I must keep to my bed until it passes; but we cannot wait for that to subdue this island. So, my friend, I wish you to take over. The time has come to conquer the entire island. We must not be satisfied with Nicosia. We must show Isaac that he has lost everything.’

‘I will do exactly as you wish,’ answered Guy.

‘Then having taken possession of Nicosia we shall be lenient with those who thought they could stand out against us. There is only one order I give: All the men must shave off their beards. This I demand for it will show their humility. If any man defies me then he must lose not only his beard but his head with it. Make that clear. And once an order is given it must be obeyed. There must be no leniency. That is the secret of good rule. All must know that when the King speaks he means what he says.’

Guy listened attentively. He would let the King’s command be known throughout Nicosia and then he would set out to subdue the rest of the island.

Richard trusted him. He liked the man. Guy would serve him well not only because he was an honest man but because he needed Richard’s support against Conrad de Montferrat, the candidate for the crown of Jerusalem whom the King of France was supporting.

He lay on his bed, tossing this way and that, the fever taking possession of him. He was a little delirious. He thought that his father came to him and told him that he was a traitor.

‘That I never was,’ he murmured. ‘I spoke out truly and honestly. I fought against you because you tried to deprive me of my rights . . . but I never deceived you with fair words . . .’

And as the waves of fear swept over him he asked himself why his father had always been against him. He seemed to hear the whispered name: ‘Alice . . . it was Alice . . .’

Alice! He thought he was married to Alice; she had become merged in his delirious imaginings with Berengaria. Alice, the child; Alice, seduced by his father in the schoolroom. An echoing voice seemed to fill the tent. ‘The devil’s brood. It comes from your Angevin ancestors. One was a witch. She went back to her master the devil but not before she had given Anjou several sons. From these you sprang. You . . . your brothers Henry, Geoffrey, John . . . all of them. There was no peace between them nor in the family.’

It was as though Philip were speaking to him, mocking him.

This accursed fever! Philip had said: ‘How will you be in the hot climates? Shall you be able to withstand the sun?’

‘As well as you will,’ he had answered.

Philip had said: ‘I believe you have had bouts of this fever for years. It’s the life you have led.’

But if he remained in his bed the violent sweating fits would pass and with them his delirium. His brain would be clear again. It was only a matter of time.

There was good news from Guy. He had taken the castles of St Hilarion and Buffavento with very little trouble and in that of Kyrenia he had found Isaac’s young daughter. He was awaiting Richard’s instructions as to what should be done with her. Clearly she must not be allowed to go free, for she was Isaac’s heiress.

All was well. He had been right to trust Guy. The fever was beginning to pass but he knew from experience that it would be folly to rise too soon from his bed.

He had given instructions that the news of his sickness was not to be bruited abroad. He did not want his enemies to set in motion a rumour that he was a sick man which they would be only too happy to do.

Soon he would rise from his bed; and if by that time Cyprus was completely subdued he would be able to set out on his journey to Acre.

When one of his knights came in to tell him that Isaac Comnenus was without and begging to be received, he got up and sat in a chair.

‘Bring him in,’ commanded Richard.

He remained seated so that Isaac should not see how weak he was.

Isaac threw himself at Richard’s feet where he remained kneeling in abject humility.

‘Well, what brings you here?’ asked Richard.

‘I come to crave mercy and forgiveness.’

‘Dost think you deserve it?’

‘Nay, Sire. I know I do not. I have acted in great error.’

‘And bad faith,’ added Richard.

‘I come to offer my services. I would go with you to the Holy Land.’

‘I do not take with me servants whom I cannot trust,’ answered Richard tersely.

‘I swear . . .’

‘You swear? You swore once before. Your swearing had little meaning.’

‘If you will forgive me . . .’

‘The time for forgiving is past. I should be a fool to forget how you swore to recompense me for your misdeeds and then tried to kill me with poisoned arrows. I would never trust you again, Isaac Comnenus.’

Isaac was terrified. If he had hoped to deceive Richard as he had before, he had misjudged the King. Having cheated once he would never be trusted again.

All his bravado disappeared. ‘I entreat you to remember my rank.’

‘Ah, an emperor – self-styled! I call to mind how you felt yourself superior to a mere king.’

‘None could be superior to the King of England.’

‘You are a little late in learning that lesson.’

‘I beg of you, do not humiliate me by putting me in irons. Anything . . . anything but that. Kill me now . . . if you must, but do not treat me like a common felon.’

‘I will remember the high rank you once held.’

‘I thank you, my lord. All Cyprus is yours now. You know how to be merciful. Have I your word that you will not put me in irons?’

‘You have my word.’

‘And all know that the word of the English King is to be trusted.’

‘You shall not be put in irons,’ affirmed Richard. He called to his knights. ‘Take this man away. I have had enough of him.’

When he had gone he sat their musing and, remembering how he had been deceived by Isaac, he laughed aloud.

He called in two knights.

He said: ‘I want Isaac Comnenus to be kept a prisoner until the end of his days. He can never be trusted while he is free. I have promised him that he shall not be put in irons. Nor shall he be. But he shall be chained nevertheless. See that he is made secure and that he is in chains. But the chains shall be of silver. Thus I shall keep my word to him. Chained not in irons but in silver.’

Richard was amused and suddenly pictured himself telling the story of Isaac Comnenus to Philip of France.

No word from Richard. Where could he be? Why did he not send a message to them? Surely he knew how anxious they had been.

Joanna tried to soothe Berengaria. He was engaged on a dangerous enterprise, she explained. It would need all his skill to subdue Cyprus. He knew they were safe and they must not expect him to be sending messages to them describing every twist and turn of the battle.

They sat together in the gardens of the house where he had lodged them.

‘Here we are,’ said Joanna, ‘in this comfortable house. We can enjoy these lovely gardens. We should consider ourselves fortunate that he is so concerned for our well-being.’

‘I know,’ said Berengaria, ‘but I think of him constantly. I wonder if he thinks of me.’

Joanna did not say that she believed that when Richard was engaged in battle, he thought of nothing but that battle. She had always guessed he would be a neglectful husband, but it was sad that Berengaria must discover this so soon.

How could this girl so newly a wife be satisfied with anything but the undivided attention of the husband she adored?

Joanna watched a green lizard dart across the grey stone wall and disappear within it. What peace there should be in this garden where there were bushes of brightly coloured flowers and the pomegranates grew in abundance among the ever present palms. So quiet it was and yet not far away there was bitter fighting. Isaac would not give in easily even though he must know that he could not stand out against Richard.

‘I heard a rumour last evening,’ said Berengaria.

‘What was this?’

‘That Isaac has a daughter who is the most beautiful girl on the Island. She is very young and she has been held as a hostage.’

‘It is inevitable that she should be.’

‘She will be . . . with Richard?’

Joanna looked astonished. Berengaria could not be jealous of Isaac’s daughter!

‘I doubt not that she will be well guarded.’

‘We have not heard from him for so long.’

‘Come, tell me what you have heard about Richard and Isaac’s daughter.’

‘That she enchants him. Joanna, can it be for this reason that we have heard nothing of him?’

Joanna laughed. ‘My dear sister, do you imagine Richard sporting with this girl while the enemy is at the door?’

‘There must be some lulls in the fighting.’

‘You have much to learn,’ Joanna smiled. ‘Listen to me, Berengaria. Isaac’s daughter may be the most enchanting creature in the world, but I’ll swear Richard would hardly be aware of this.’

‘Surely any man would be.’

‘Not Richard.’

‘You seek to comfort me.’

‘So that is what has been ailing you. You have been jealous. You have listened to malicious gossip. I’d be ready to swear that Richard is aware only of Isaac’s daughter as a hostage.’

‘I wish I could believe that. But we have not heard for so long.’

‘Berengaria, now that you are married to Richard you will have to understand that there may be long periods when you hear nothing from him and have no idea where he is. He is a soldier . . . the greatest living soldier . . . and he will always be engaged in some conflict. Now it is the conquest of Cyprus. Later it will be an even greater enterprise. You will need much patience and loving understanding. You must realise that.’

‘I do. I do. But we have not heard and there is this girl. She is with him. People are talking.’

‘People will always talk. Heed them not. Love Richard, and most of all never question him. He would not like that. He must be free. If you would lose his regard the quickest way to do so is to make yourself a burden to him. He has put you . . . indeed both of us . . . in a safe place. That was his great concern. Be grateful that he is so anxious for our welfare. It is the measure of his affection for us. I would be ready to wager a great deal that there is nothing in this gossip. I know Richard . . .’

She stopped and looked at Berengaria rather sadly. What if she told Berengaria the real reason? What if she said: Richard is not like some men who think that women are part of a conquest. Richard is not very interested in women.