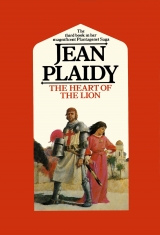

Текст книги "The Heart of the Lion "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

‘To be more greatly feared than Philip the Lamb.’

‘Do not underestimate me, Richard.’

‘Nay, I should not be so foolish. If I did you would be reminding me of my Dukedom in Normandy.’

‘You know that the friendship between us is greater than any rivalry. You know that we are friends before King and vassal.’

‘Or King and King.’

‘Aye, my Lord of England. And how I rejoice that at last you have come.’

He was not the only one. Bonfires were lighted that night. They sprang up everywhere in the Christian camp. The crusaders sang of his exploits. They had begun to call him the Lion-hearted.

In his camp Saladin heard the sounds of rejoicing and he knew that the name of Richard the Lion-Heart struck terror into the hearts of his men.

He wanted very much to come face to face with this hero whose fame had spread through Christendom and into his own ranks.

In the tent the two Queens waited for Richard to come to them. To Berengaria it seemed strange that she was never alone with her husband. She knew, of course, that he had a Holy War to fight; the sight of the camps and military activity before the city filled her with apprehension and the thought of what those people within its walls must be suffering made her very sad.

‘I know they are not Christians,’ she told Joanna, ‘but they are people. I have heard that they are starving.’

‘If that is so,’ said Joanna, ‘they will not hold out much longer and then it will all be over.’

‘It will not be the end,’ said Berengaria sadly. ‘When they have taken Acre, what next? There will be more fighting, more camps like this. I thought we were all going to die during that terrible battle with the Saracen ship.’

‘Nay, we’ll not die. Richard will take too much care of us for that.’

Did she really believe it? wondered Berengaria. She herself had changed a little. She was beginning to realise that Richard was not over anxious for her company. If he were surely there would be some time when they could be together?

The little Cypriot Princess who was constantly in attendance listened to their conversation and wondered what would become of her and whether she would ever be allowed to go home to her father.

Richard seemed to have forgotten their existence, though they heard that he often rode out with the King of France.

‘He spends a great deal of time with Philip,’ Berengaria commented, ‘although he has little to spare for us.’

‘It is good for the men to see them together,’ Joanna excused him. ‘It gives them confidence in their leaders.’

One day Richard did come to their tent, and with him was the King of France. Richard was kind and enquired after his wife’s health but it was not the occasion for intimate conversation. As for Philip he was very courteous, particularly to Joanna, but as Joanna said afterwards to Berengaria, it did not mean anything.

‘Would you like to be Queen of France?’ asked Berengaria.

‘No. If I married again I would wish to marry for love.’

‘Perhaps you could love Philip.’

‘I do not think I could and I would not want to marry merely because it would be a link for our two countries if I did. I believe that a Princess may be in duty bound to marry in the first place for state reasons, but when that marriage is over she should have a free choice.’

‘Yet if Philip offered for you?’

‘I could refuse.’

‘Even if Richard wanted it?’

‘Let us not consider that. At the moment neither of them has time for women. They have their battles to think of.’

‘I believe some of the men have time for their women.’

‘They are not kings,’ said Joanna shortly. She turned to the little Cypriot and said: ‘You listen. Perhaps you are wondering when a husband will be found for you?’

‘Do you think there ever will be?’

‘I am sure of it. Richard will find a husband for you when he is no longer preoccupied with his battles.’

And when would that be, wondered Joanna. She could not imagine Richard without a war to fight.

Richard was preoccupied with the coming assault on the walls of Acre. He had brought with him several contraptions which it was necessary for him to assemble. There was, of course, his tower, the Mate Griffon, on which men were working so that when the time came it could be wheeled into position. There was another machine known as the Belfry; this like the Mate Griffon was intended to be placed close to the walls of the city when the time was ripe for entry. Because of the Saracen’s frequent use of Greek Fire, Richard had ordered that it should be covered with tanned hides as a protection against the fire. Another of his machines was a war engine which was used for throwing stones high in the air and at great speed so that they fell into the city. This mangonel had been called the Bad Neighbour and when the Saracens invented a similar machine to throw stones back among the Christians this was nicknamed the Bad Kinsman.

All through the days that followed Richard’s arrival work went on to make these war machines ready for use. The spirits of all the Christians had been so lifted by the arrival of Richard that they forgot all they had suffered through the abortive attempts to take the city, even the discomforts of the khamsin and the devastating effect the terrific heat had on them. When he rode round the camps he was cheered by all nationalities and they all felt comforted by his presence. He was so certain of victory that he communicated his confidence to them. This uplifting of spirits was obvious even to the Saracens encamped beyond the city on the hill of Ayyadieh.

Saladin himself talked of it with his brother, Malek Adel. ‘What manner of man can this Richard be? They call him the Lion-hearted. They say he is brave and never knows defeat. There is a change in their ranks since he has come.’

Malek Adel replied that they would soon prove to the Christians that their hero was but human after all. He promised Saladin that he himself would bring him Richard’s head and that without his body.

Saladin shook his head. He was not given to such boasts nor did he care to hear his brother talk in such a fashion. He believed that Allah did not love the boastful; and he knew from experience that it was never wise to underrate an enemy.

His men looked to him and expected miracles from him and because they believed so fervently that these would come, they sometimes found their miracles. So must it be with this King Richard.

We are of a kind, he thought. It is a pity that we should fight against each other. But they were two men each with his fixed idea – Saladin’s to hold Jerusalem and Richard’s to take it.

In the midst of the activity Richard fell ill. The recurrent fever took possession of him and though he attempted to fight it off with all his strength, he failed to do so.

How maddening it was to be laid low where he could hear the noise from the anvils as the great war machines were perfected. The action would have to be delayed and this would give the Mussulmans time to prepare. They must have seen the swelling of the Christian ranks. Their spies would have taken back reports of the great war machines. And now the fever had come to torment him!

Berengaria came with Joanna to his tent. They were horrified at the sight of him.

‘I am not so ill as I look,’ said Richard. ‘I know this accursed fever by now. It will pass. It infuriates me, though, that it should come at this time.’

‘At least,’ said Berengaria, ‘now we can look after you.’

And they did. Through the haze of his fever Richard was aware of soft and gentle hands that smoothed the hair back from his face, and put cooling drinks to his lips.

When she could forget her anxieties for his health, Berengaria was happier than she had been since the first days of her marriage.

As the fever grew less virulent, he would ask anxious questions about what was happening outside his tent. She would soothe him and say: ‘All is well.’

How could it be, when he was on a sickbed? he demanded irritably. Who was going to break the siege?

‘The siege can wait,’ said Berengaria; and he sighed in exasperation at her feminine ignorance.

How could he talk with Berengaria? Joanna would have understood more readily. Joanna was there but she kept in the background knowing what pleasure it gave Berengaria to attend to her husband. He was also aware of a third figure – a very young girl of great beauty who seemed like Berengaria’s shadow.

Once he said: ‘Who is the girl?’

‘Isaac’s daughter.’

He was immediately alarmed. ‘What does she here?’

‘She is with us all the time. You gave her into our charge remember.’

‘Her father is my prisoner. She could be looking for revenge.’

‘Nay. We have taught her that you are the noblest king that ever lived.’

He was uneasy. But Berengaria soothed him. The little Cypriot Princess was innocent. She was with her and Joanna all the time. She was like a little sister. She would never harm any whom Berengaria loved. Moreover Berengaria herself prepared his food. She would trust no other to do so.

He watched the girl; it seemed Berengaria was right. None could imagine evil in such a dainty child. Berengaria became a little jealous.

‘You find her beautiful?’

‘The Cypriot women have a certain charm.’ He was suddenly remorseful for his neglect of Berengaria. ‘Not to be compared with those of Navarre,’ he added.

That contented her. It was easy to please her and he felt happy in his marriage for the first time. When he was well he would pay more attention to Berengaria. She was a good woman and by no means ill-favoured; he liked her natural elegance, and it was comforting to feel her there when the fever took possession of him.

Philip came to see him. He stood by the bed looking down on him.

‘So the fever can do what no human enemy can. My dear Richard, you look very ill.’

‘It will pass.’

‘This accursed climate! How do the natives endure it?’

‘They are accustomed to it, I doubt not. Their robes protect them from the sun and so they remain cool.’

‘How I hate it!’ cried Philip vehemently. ‘Flies and sand in everything . . . in one’s clothes, in one’s hair, in one’s food. The mosquitoes are a pest. Some of my men have died of their bites. The terrible spiders are a danger. Their sting is death. They come out when it is quiet and the men are asleep. Several men have been killed by these tarantulas. We have found that they dislike noise and it drives them away, and the men clash symbols before they lie down but they cannot continue this throughout the night and as soon as quiet falls the danger returns. Sometimes I think of home, of my fair land of France where it is never too hot, where there is no sand to plague me . . . no dust, no poisonous spiders . . . And now you are sick, Richard. In God’s name let us take this town and then go home.’

‘When we take this town that is but a beginning,’ protested Richard. ‘After that we have to march on to Jerusalem.’

Philip clenched his fists and was about to speak but he changed his mind.

After a pause he said: ‘And it grieves me to see you thus. You too need the temperate winds of home.’

‘We took an oath, Philip. We are soldiers of the Cross. Do not forget that.’

‘I forget it not. That is why we are going ahead with the assault on Acre.’

‘I am in no condition, I fear, and shall not be for a week or so. I know these bouts. The truth is, Philip, if I tried to stand on my feet I should fall.’

‘Then you must rest. In the meantime I shall begin the assault.’

‘But, Philip . . .’

‘I know we were to do it together. But Saladin is arming. He knows the assault is coming. We cannot delay further. You were so long in getting here. We dare not delay longer.’

Richard looked up at that sly clever face which he knew so well.

Perhaps somewhere in Philip’s mind was the thought that if he took Acre without Richard, to him would be the glory.

There was love between them, yes, but there was something else; this irrepressible rivalry. The desire to score over the other would always be there. They excited each other more than any other person could. There was a love relationship between them but sometimes there was something near to hate.

Richard who always said exactly what was in his mind burst out: ‘You want the honour for yourself. You do not want to share it.’

‘My dearest friend, get well. Join me. Nothing would please me more. But delay I cannot. Even for your sake I cannot run the risk of defeat.’

‘I forbid you to start without me. Oh I know what you will say. The Duke of Normandy forbids his suzerain!’

‘And you will say the King of England is perfectly entitled to challenge the King of France. Forget our ranks, Richard. Know this: I am going into battle. You are too ill to join the fight. Your men may. You will not hold them back. For I am going to take Acre and that within the next few days.’

Richard was silent. He knew he could not prevail upon Philip to wait.

The battle had begun. Richard could not stay in his tent while this was going on. He tried to stand but he was too weak from fever. He could not go out there and join in the fight.

He called to his servants and commanded them to bring him a litter. This was done and when he lay on it he asked for his cross-bow.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘carry me out.’

They hesitated and he shouted at them: ‘Obey my orders, you oafs. Do not dare defy me.’

They were afraid and did his bidding and he insisted that they carry him to a spot near the walls of the city. There under cover of raw hides he watched what was going on and when he saw any of the enemy appear on the battlements he took a shot at them with his cross-bow, and as he was the finest shot in the army he rarely missed his mark.

But this was Philip’s assault. Richard could not be in command from his litter and this gave the French King his opportunity. He was determined to succeed . . . without Richard. He longed to be the master. Again and again he thought of those happy days when they were younger and Richard was not yet a king, his inheritance in jeopardy because of his father’s hatred of him and determination to put John in his place. The King and the beloved hostage. That was the way he wanted it.

And now this rivalry had been formed to corrupt their relationship. Both of them perhaps were kings before they could be lovers.

If he could take Acre while Richard was actually on the spot, this would indeed be glory. Some might even say that Richard had feigned illness because he knew he could not compare with the King of France. A ridiculous statement of course, and Philip would be the first to admit that Richard was his superior on the battlefield, but there was no end to the foolish things people said, and desperately Philip needed the glory Acre could give him.

He was going to take the Accursed Tower. That was important. The Tower which had been built with the thirty pieces of silver given to Judas and had before withstood his attack. He would undermine that Tower; it should crumble; the bricks should be taken away so that in time it tottered to the ground.

Over the walls of the city flew the deadly stones discharged by the giant mangonels; but down from the walls came the deadly Greek Fire.

One of Philip’s greatest delights was a movable screen of mantelets which had been given the name of The Cat. This protected his soldiers from arrows and stones. He had ordered that it be wheeled close to the walls and he himself was there to watch its protective effects. To his great dismay the Greek Fire sent down upon the attackers from the walls of the city caught it alight. Philip groaned in despair as he watched it burn.

Everything seemed to go wrong after that. Philip shouted abuse at his men and at God. It was so rare for him to lose his temper that they were aghast. The French King must be deeply disturbed so to lose his calmness in this way; the English King was suffering from a fever, and the Saracen armies seemed unconquerable. The Christian foot soldiers in their heavy armour over long padded coats, suffered cruelly from the heat. The only asset of these accoutrements was that often arrows could not penetrate them. Some were seen walking about with arrows lodged in their mail and which would have killed them but for it. But the discomfort was hard to bear.

Philip longed for France; he cursed the day he had sworn to set out on a crusade. How different the reality was from the dream! It had seemed so desirable. Marching along at the head of his men, making easy conquests, scoring over Richard – which did not seem too much to hope for since what he lacked in military skill he made up for in subtle diplomacy – winning glory, and a remission of his sins. And the reality – dust, the ever-present sand, the flies, the mosquitoes, the tarantulas and the incessant heat.

I want to go home, thought Philip. Oh God I would give anything to go home.

The Accursed Tower would not fall. Even when they made a breach in it it was not enough to break through. Seeing his dismay one of his finest soldiers, his Marshal of France and dearest friend Alberic Clement, cried out to him: ‘Despair not, Sire. I swear that this day I will either enter Acre or die.’

Alberic fixed one of the scaling ladders and sword in hand started to climb with some of his men following him.

God was not with them that day, mourned Philip. The ladder broke and the men fell to the ground with the exception of Alberic who was left alone hanging there exposed to the full fury of the enemy’s fire.

To see this dear friend die deeply wounded Philip.

He turned away from the arrows and the Greek Fire and went back to his camp.

He had begun to shiver. He was suffering from the same symptoms as those which had beset Richard.

So the siege of Acre had not been broken and the two kings were sick. The crusaders were despondent. They cursed God. They had come all this way to fight for His Holy Land and He had deserted them.

The fighting had slowed down. Richard was still carried out and beneath his protection of raw hides took shots at any enemy who came within his range. He was thus able to kill the Saracen who appeared on the wall of Acre wearing the arms of Alberic Clement. This gave him great satisfaction for he had heard of that brave attempt to scale the wall. But the fact that the King of France was indisposed and that he himself was ill had made the soldiers apprehensive. They feared they were to be left without leaders.

Richard began to think a great deal about the enemy and the man who led them, the great Sultan Saladin. The stories he had heard fascinated him. He had not before thought of a Mohammedan as human but it appeared that this man Saladin was humane, a man of sensitivity and culture. The fanatical manner in which his armies fought had long been a source of wonder and it seemed that these men were fighting for a cause even as the Christians were.

Saladin’s name was mentioned with an unmistakable awe.

As he lay on his litter cursing the evil fate which had smitten him down at this time, he wondered if it would be possible for them to meet.

Saladin himself was thinking a great deal about Richard. He had been aware of what was happening in the Christian camp. The spies who slipped into enemy terrain kept him well informed of what was going on. From the heights of Ayyadieh he had seen the arrival of Richard’s fleet; he had heard of his conquests in Sicily and Cyprus, and he felt a great desire to see this man, whose fame had spread throughout the Moslem Empire.

He talked of him to his brother Malek Adel, who was delighting in the news which had been brought in of Richard’s sickness.

‘We see in this the hand of fate,’ said Malek Adel. ‘As we feared our people in Acre could not endure the siege much longer, and lo, the great Richard has fallen sick. Allah has answered our prayers.’

‘Let us not be too sure that he will not rise from his sickbed. It may be that he has already done so.’

‘The people in Acre will be rejoicing,’ said Daher, Saladin’s son. ‘It is said that the great King is unable to walk, is carried out on his litter and lies there with his cross-bow. If we could find him thus we could capture him or kill him. Where would they be without their leader?’

Saladin shook his head. ‘I would not wish it. I do not care to take advantage of a great King thus.’

‘My lord,’ cried Daher, ‘he is our enemy.’

‘’Tis true, my son, but one must respect one’s enemy. I want to overcome him in fair battle, not to slip in and take him while he lies unprotected.’

‘Is this the way to win a war?’ asked Malek Adel.

‘It is the honourable way to conduct a war,’ retorted Saladin.

While they talked one of the soldiers begged for an audience. His news was that a magic stone thrown from one of the enemy’s war machines had landed in the centre of Acre and had killed twelve people.

‘One stone to kill twelve!’ cried Daher. ‘I do not believe it.’

‘It is so, my lord,’ replied the soldier. ‘I saw it with my own eyes. I narrowly escaped being one of its victims. It was large but there have been others as large. It landed in the town square and killed the twelve.’

‘It’s unbelievable that one stone could do this,’ said Saladin.

‘If it did, it was magic,’ replied Malek Adel.

Saladin said that he would see this stone and he ordered that it should be brought to him.

This was done. It was set down and they examined it. There was nothing extraordinary about it as far as the eyes could see, but when the number of deaths from this one stone had been confirmed there was no doubt in the minds of the Mohammedans that the stone had been given some special properties.

Malek Adel wanted to try it against the enemy, but Saladin did not want to lose the stone. It was to be preserved and studied. A stone which could kill twelve people at one throw must have magic properties.

Into Saldin’s camp came a messenger. He was a daring man to brave coming into Saracen lines, but Saladin was not one to allow such a man to be ill-treated. He had given orders that this was not to be so, for such messengers came on the orders of their leaders and unless they behaved with insolence and arrogance they were to be well received.

‘I come from King Richard,’ said the messenger.

Saladin asked all to retire except his brother Malek Adel.

‘Pray state your business,’ he said.

‘King Richard wishes you to know that he believes there could be much good in a meeting between you and himself.’

Saladin was excited at the prospect. He looked at Malek Adel about whose lips a cynical smile was curving. Saladin was too astute to allow a personal desire to influence him and much as he desired to see Richard and talk with him he must view this approach with the utmost care.

Malek Adel said: ‘So the King of England is sick. He despairs of taking Acre. Therefore he would like to talk peace.’

This could be so, thought Saladin, but it was true that the besieged town of Acre was in a pitiful state. When he had heard of the lost ship, which Richard had sunk, he had cried out in despair, ‘Allah has deserted us. We have lost Acre.’ And it was a fact that the loss of all that ship was bringing to the beleagured city could have a decisive effect on its survival. It was true that Acre was not yet taken but it could fall at any moment. Another assault could bring the citisens to their knees. There had been an arrangement that if they were in dire distress within the town they should indicate to the army on the heights that this was so by the beating of kettle drums. During the recent assault those kettle drums had been heard.

It was typical of Malek Adel to display this blind confidence in their armies. Saladin applauded it up to a point. Confidence was essential, but this must be tempered with sound good sense.

‘Your King lies sick,’ he said to the messenger.

‘It is an intermittent fever,’ was the reply. ‘He has had it before. He will rise from his bed in due course as strong as he ever was.’

‘’Tis not what I heard,’ growled Malek Adel.

The messenger said: ‘My King offers to meet you, my lord.’

Saladin said slowly: ‘There is much to be settled first. After eating and drinking familiarly we could not fight afterwards. That would be offensive to our beliefs. The time is not yet ripe for a meeting.’

‘My King wishes to show his good will by sending you gifts,’ said the messenger.

‘I could not accept gifts from him unless he took them from me in return.’

‘My King says: “It does not become kings to slight each other’s gifts even though they are at war. This is one of the lessons our fathers taught us.”’

‘It is is true,’ replied Saladin. ‘If the King will accept gifts from me I will take gifts from him.’

‘My lord, we have eagles and hawks which my King would send you. But these birds have suffered from the long sea journey and a lack of rightful food. If you would give us some fowls, and young pigeons with which to feed them, my King would then present them to you.’

‘Ah,’ said Malik Adel, ‘you see what this means, my brother. The King of England is sick, so he longs for doves and in due course he will send hawks to us.’

‘I will deal with this matter as my heart dictates,’ said Saladin. ‘None in the world could have aught but respect for King Richard. Let this messenger be clothed in fine robes and give him safe conduct back to his King with young pigeons and fowls and turtle doves.’

Malek Adel was astonished but even he dared not criticise too strongly the Sultan’s action.

The messenger went back to Richard with an account of what had happened.

The fever had returned. Doubtless due to the inclement air it was not as easy to throw off as it had been on other occasions. He was a little delirious. Once more he fancied he was with his father and he felt a terrible remorse because of the ill feeling between them. It was only when he was ill that he felt this. When he was strong he was convinced that his sons’ enmity was entirely their father’s fault.

Philip haunted his mind. He had at first believed that Philip was feigning illness because he wanted an excuse to go home. But this had proved to be untrue. He had heard that Philip’s hair was falling out and his nails flaking off and that he was in a very poor condition. ‘It’s this climate,’ he wailed continuously. ‘This accursed climate . . . this dust . . . these insects . . . they are killing me.’

It was said that his longing for France was an illness in itself.

Are we both going to die? wondered Richard.

If so, they would die with their sins forgiven for how could a man die in more sanctified state than in a campaign to bring the Holy Land back to Christianity?

There was Saladin. A great man, a good man. Who could believe that a man who was not a Christian could be good? Yet it seemed so. He had noticed how Saracen prisoners spoke and thought of their leader. If my men think thus of me I am happy, thought Richard. How could a man who was not great and just inspire such respect?

They did not believe in Christ, these Saracens. But they believed in Mahomet. He it seemed was a holy man. He had laid down a set of rules even as Moses had, and it seemed they were good rules.

And yet how could a man who was not a Christian be a good man? Yet were all Christians good? Richard found himself laughing in a hollow way.

Then he thought: I am dying. This accursed fever has caught up with me at last. I should never have camped in the swamping ground all those years ago. How the insects plagued me! Those maddening mosquitoes. And here they are again . . . worse than ever!

And if I die what will become of England, of Normandy? Philip will take Normandy. He is waiting for the chance. What of John? Will John try to take England? And what of young Arthur whom I have named as my heir?

As the waves of fever swept over him he started up, for it seemed to him that someone had slipped into his tent. It was one of the guards.

‘My lord, there is one who says he must speak with you. He is unarmed. Will you see him?’

I am too ill, thought Richard. But he said: ‘Bring him in.’

The man knelt by the bed and laid a hand on his brow. It seemed cool and soothing. There was a certain magic in its touch.

‘Who are you?’ asked Richard.

‘One who comes in friendship.’

‘You are not an Englishman.’

‘Nay. I would speak with you alone.’

‘Leave us,’ cried Richard to the guard. The man hesitated but Richard cried: ‘Begone.’

When they were alone Richard said: ‘What brings you?’

‘You are near to death and I come in friendship.’

‘Tell me who you are.’

‘Perhaps you know.’

‘It cannot be.’

‘Do you feel this bond between us? I have heard much of you. I craved to see you. You are in a high fever.’

‘I am seeing visions,’ said Richard.

‘It could be so.’

‘Saladin . . . why are you here?’

‘I felt the need to come. I have a magic talisman. If I touch you with this and God wills it, the fever will pass.’

‘You are my enemy.’

‘Your enemy and your friend.’

‘Is it possible to be both?’

‘Lo, we have shown it to be.’

Richard felt something cool pass over his brow. ‘I have touched you with my talisman. The fever may now pass. There are foods you need now to strengthen you – fruit and chicken, such things as you do not possess in the camp. These will be sent to you. You will recover.’

‘Why do you come to me with succour?’

‘I understand not my feeling except that I must. We shall fight together and one of us will be victorious. It may be that we shall die in battle. Yet this night we are friends. We could love each other but for barriers between us. Your God and my God have decreed that we shall be enemies, and so must it be. But for this night we are friends.’

‘I feel comforted by your presence,’ said Richard.

‘I know it.’

‘If you are he whom I believed you to be, I am filled with wonder. While you are near me the fever slips from me. But I have suffered such delirium that I tell myself I am in delirium now.’

The cool hand once more touched his brow.

‘This is no delirium.’

‘Then if you are who I think you are . . . why did you come here . . . right into our midst?’

‘Allah protected me.’

‘I shall add my protection to his when you go back. You shall not be harmed by any man of mine while on such a mission.’

‘We shall meet again,’ was the answer.