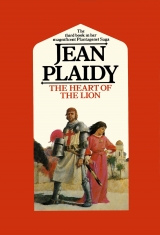

Текст книги "The Heart of the Lion "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

There was no time to lose. If Richard captured him . . . He shivered at the thought.

Taking with him a few of his attendants he rode to Rouen where he knew Richard and Eleanor were; and he managed to find a way into the Queen’s apartments.

He threw himself at her feet and begged her clemency.

‘John,’ cried Eleanor. ‘So you have come then!’

‘Yes, Mother,’ answered John, ‘and in most wretched state as you see.’

‘Oh, John,’ cried Eleanor, ‘what have you done?’

‘I have been foolish, Mother. Do not reproach me, for your reproaches could not match my own. I have been wicked. I have been wrong. I have been led astray by evil counsellors. How can I face my brother?’

The Queen replied: ‘You have in truth been wicked, John. You have plotted against the finest man in the world.’

‘I know it. I know it now. Would to God I had not listened to those evil men.’

‘Aye, would to God you had not.’

‘Mother, you are wise, you are good. I want you to tell me what I must do. Shall I take a sword and pierce my heart? I think that would be best. First though, I would wish to prostrate myself before my brother. I would wish to show him my contrition. I want him to know how miserable I am, how I hate myself, and perhaps to ask his forgiveness and that of God before I take my own life.’

‘You are talking nonsense,’ replied Eleanor sharply. ‘Put thoughts of taking your life out of your head. I would not wish any son of mine to act in such cowardly fashion.’

‘But I have offended . . .’

‘Deeply,’ she cried. ‘Your God, your King and your country.’

‘I must be the most hated man alive. There is no reason for me to live.’

‘Stop such talk! I am your mother and I could not hate you.’

‘You hated my father when he worked against Richard. You have always loved Richard and hated those who worked against him.’

‘I love all my children,’ she answered, ‘and I never truly hated the King, your father. You could not understand what there was between us. But that is of the past. It is the present that matters. You have proved yourself a traitor and there are few kings who would not condemn you to the traitor’s death. But Richard is your brother. He is by nature tolerant. I am your mother and whatever you have done you are still my child.’

‘What should I do then, Mother? I beg you tell me.’

‘Leave this with me. Go away quietly. I will speak to your brother and mayhap he will send for you and perhaps he will find it in his heart to forgive you. If you should be the luckiest traitor in the world, then remember what great fortune is yours and serve him with all your might and heart for as long as he shall live.’

‘Oh, my mother, I would. I swear to God I would.’

‘Then go and leave this matter to me.’

When he had gone Eleanor was thoughtful. She knew him well. He was avaricious; he was weak; he wanted the crown. But he was her son. She could not get out of her mind what a pretty baby he had been and how she had loved him – the youngest, the baby. It had been one of the tragedies of her life that she had not been able to keep her children with her.

He deserved death or imprisonment, but he was her child.

Richard would forgive him if she asked it, she knew. And if he were forgiven, there must be an heir to the throne. Richard was not an old man: he had many years ahead of him. She wanted to see some healthy sons before she died.

Richard might pardon John and if he did he must call Berengaria to his side. He must live with her. It was imperative that he have sons to ensure the succession.

It would be a tragedy for England if John ever came to the throne.

It was Eleanor who brought him to the King.

Richard looked at his brother and thought: As if he could harm me!

John ran to him and threw himself at his feet.

‘You tremble?’ said Richard.

‘My lord, I have sinned against you. I deserve any punishment you should give me. I cannot understand myself. I was possessed by devils. How otherwise could I have gone against the brother whom I revere as does all the world?’

‘’Twas not devils,’ said Richard, ‘but evil counsellors. Come, John, do not fear me. You are but a child and you fell into evil hands.’

He rose and drew John to his feet. He kissed him. It was the kiss of peace and pardon.

‘Come,’ he said, ‘we will go and eat and from now on there shall be harmony between us.’

All those who were present marvelled at the King’s generosity or simplicity. The fact that he had returned and was in power could by no means have diminished John’s ambitions. But Richard seemed to be of the opinion that it did.

One of his servants brought in a salmon which had been presented for the King’s table.

‘A fine fish,’ said the King. ‘Cook it and I will share it with my brother.’

John was relieved but at the same time resentful; he knew that Richard’s leniency meant that he had little respect for him.

Well, he must be quiet for a while. He must watch his actions and wait for the day when the crown would be his.

Eleanor expressed her pleasure that the brothers had been reconciled.

‘You are magnanimous, Richard,’ she said. ‘I do not believe many kings would have been so.’

‘Bah,’ said Richard. ‘What is John but a child? He could never take a kingdom. His only chance of getting one would be if it were handed to him without a fight.’

‘Is that what you intend to do . . . to hand it to him?’

‘I am not dead yet, Mother.’

‘Nay but you are ten years older than John. It is thirty-six years since I bore you. You must get an heir or there will be trouble, Richard. Why do you not send for Berengaria?’

‘There is much yet to be done. I don’t trust Philip. I shall be engaged here in Normandy for some time.’

‘She could be here with you as I am now.’

‘Mayhap,’ he said; and she knew that he did not intend to have her.

The next day he said: ‘I shall send for Arthur. He should be brought up in England.’

‘That you might make him your heir?’ replied the Queen.

‘Is it not wise to have him brought up in the country he may well govern?’

‘He would only be the heir, Richard, if you did not have sons.’

‘It is well to be prepared,’ replied Richard. ‘If he should be displaced it will have done him no harm to have had an English upbringing. Why, Mother, what ails you? You are thinking that it would go ill for England if John were King. That is why we send for Arthur.’

Eleanor understood. Richard meant that he was not going back to Berengaria.

Chapter XX

Chapter XX

REUNION WITH BERENGARIA

The King was riding to the hunt in the Normandy forest. Like his ancestors he loved this sport and found greater relaxation from it than in any other way.

It was a year since he had been released from captivity; it had been a year spent chiefly in fighting, subduing those who would rise against him, regaining those castles which had fallen into other hands while he was away.

He had not seen Philip in that time but there had been opportunities when they might have met. Neither wanted it, certainly not Philip. He could never have faced Richard after all his perfidy; he could never have explained what had prompted him to betray him, to seek an ally in John when Richard was in prison. He thought of him constantly though; and if Richard could not be his loving friend, he found some consolation in being his enemy.

A great deal had happened. Joanna had married and had given birth to a child. She was happy with her Count and Richard was glad of that. The Princess Alice, who had once been betrothed to him and had been the mistress of his father, had been returned to her brother after a treaty he and Richard had made. Poor Alice, she had not had much of a life since the death of King Henry. Perhaps there would be a change when she went to France. And so it had proved to be, for Alice, now thirty-five years of age, was married to the Count of Ponthieu who evidently believed that alliance with the royal house of France was worthwhile even if it meant taking a princess who was no longer young and about whom there had been scandal in her youth.

Richard hoped Alice would at last find peace.

His sister-in-law Constance had refused to send Arthur to him. Clearly she did not trust him. What a fool the woman was! Surely she wanted Arthur to have his rights and there was no doubt that he was the heir to the English throne. Had he lived Geoffrey would have been pleased to see his son so elevated. But an English king should know the English and the best way of doing that was to be brought up among them.

Yet Constance had sensed some intrigue. She did not trust her brothers-in-law. That she did not trust John was understandable as Arthur would displace him, but why not Richard? She had even sought the aid of Philip to help her against Richard, and he had heard that she had sent her son to the Court of France to avoid his being taken by the English.

Richard shrugged his shoulders. If that was what she wanted let her have it. It could well lose her son the throne. John was at least known to the English. Oh God in Heaven, thought Richard, what would happen to England if John were King!

His Mother would say: Get heirs of your own. All that is needed is a son of yours.

No! he cried, and tried not to think of Berengaria lonely in the castle at Poitou. Joanna had gone now and even the little Cypriot Princess had been returned to Leopold’s wife in Austria who was her kinswoman.

Leopold had died recently. He had fallen from his horse and broken his leg which mortified to such an extent that amputation was necessary. Knowing that if it were not removed it would corrupt his whole body he himself held the axe while his chamberlain struck it with a beetle. He had courage, that Duke, thought Richard; but after his leg had been cut off he died in terrible agony which many said was Heaven’s retribution for his treatment of Richard the Lion-hearted who enjoyed favour from above on account of his having brought Acre to the Christians.

One day, thought Richard, I will go back to the Holy Land.

Saladin was dead. His intimate, the Saracen Bohadin, had told how nobly he had died. He was both brave and humble and talked of the perishability of earthly possessions. He told those about him to reverence God and not to shed blood unless it was necessary for the salvation of his country and to the glory of God. ‘Do not hate anyone,’ he had said. ‘Watch how you treat men. Forgive them their sins against you and thus will you obtain forgiveness for yours.’

Oh Saladin, thought Richard, would we could have met in different circumstances! But how could it have been otherwise than it was? I a Christian, you a Saracen; yet I would have trusted you as I could few men and I knew that you felt thus towards me.

Thinking of these matters he had ridden a little ahead of the party. It was often so, for he liked now and then to be alone; and as he came to a clearing in the woods a man ran forward and stood before him.

‘Who are you, fellow?’ demanded the King.

‘None that you would know, sir. But I know who you are.’

‘Who am I?’

‘A king and a sinner.’

Richard laughed aloud.

‘And I would say you are a bold man.’

‘You too, sir, for you will have need of your courage when you are called on to face a King far greater than any on earth.’

‘Oh, you are calling me to task for my wayward life, is that it?’

‘Repent, while there is time.’

‘Am I not a good king?’

‘The life you lead is not a good one.’

‘You are insolent, fellow.’

‘If truth be insolence then I am. Remember the Cities of the Plain. God moves in a mysterious way. Repent, lord King. Turn from your evil ways. If you do not you will be destroyed. The end is near . . . nearer than you think. Repent, repent while there is still time.’

A sudden rage seized Richard. He drew his sword, but the man had disappeared among the trees.

He remained in the clearing staring ahead of him. Thus his friends found him.

‘What ails you, Sire?’ asked one of them.

‘’Tis nought. An insolent fellow . . . a woodman mayhap.’

‘Dost wish us to find him, Sire?’

Richard was silent for a few moments. Find the fellow. Cut out his tongue. Make him remember to his dying day that on which he had insulted the King.

Nay. It was the truth. He had reverted to the wildness of his youth. The manner in which he behaved was truly not becoming to a king. A man should not be smitten for speaking the truth.

‘Leave him,’ he said. ‘Doubtless he was mad.’

It was but a month or so later when he was plagued by an attack of the tertian fever. The ague possessed him more firmly than ever before. He felt sick unto death and as he lay on his bed he remembered the man of the woods.

Pictures of his past life kept flashing before his eyes: Rearing horses, showers of arrows, boiling pitch falling over castle walls, the lust of battle which had sometimes overcome his sense of justice. Now and then he had killed for the sake of killing. He thought of the Saracen defenders of Acre whom he had caused to be slaughtered in a fit of rage because Saladin had delayed keeping to the terms of their agreement. Thousands slaughtered on the whim of a king – and not only Saracens, for Saladin had naturally been obliged to retaliate and slaughter Christians. He had always wanted to be just and honourable in battle. So often he had been lenient with his enemies. Why must he forget those numerous occasions and remember the isolated few when he had lost all sense of honour in order to appease his temper? And there was one other to whom he had caused great suffering. Berengaria! He remembered her at the tournament at Pampeluna, a fresh innocent child. Her eyes had followed him with adoration and he, knowing then of his father’s relationship with his betrothed Alice and determined to have none of her, had decided that he would take Berengaria. Yet he wanted no women and none knew that better than he. He had married her though. Kings must marry whatsoever their inclinations. They must get heirs. If they did not there was trouble. John . . . Arthur . . . what of the future? If he were to die now with his sins upon him . . .

One of his servants came into the room.

‘My lord, there is one without . . .’

Before Richard could answer a man had come into the room. He stood over the bed, the servant cowering in the background. Richard saw him through a haze of fever.

‘Who are you,’ he asked, ‘the angel of death?’

‘Nay, Sire,’ was the answer, ‘he has not come for you yet. It is Hugh, your Bishop of Lincoln.’

Richard closed his eyes. That old man whom many thought a saint; one of those churchmen who was not averse to acting against his own interest in what he believed to be right. Uncomfortable people! His father had found the leader of them all in Thomas à Becket.

Recently he had quarrelled with this man over a priest whom Richard wished to install in Hugh’s See and Hugh had objected to the King’s choice. Richard had told the Bishop that as he did not want this priest, he, Richard, would be prepared to allow things to remain as they were if the See would make him a present of a fur mantle at a cost of a thousand marks. Hugh had replied that he had no knowledge of furs and could not therefore bargain for a mantle but if the King wished to divert the funds of the See to his own use and there was no other way of settling the matter, Hugh had no alternative but to send him one thousand marks.

This incident had created a coolness between them and the King reasoned that Hugh had come to crave his pardon.

‘Why do you come?’ asked Richard.

‘I come to ask that there be peace between us, my son,’ answered Hugh.

‘You do not deserve my goodwill,’ muttered Richard. ‘You have stood against me.’

‘I deserve your friendship,’ answered Hugh. ‘For hearing of your sickness I have travelled far. In what state is your conscience?’

‘Ha, you have decided to kill me off. I tell you this, prelate: my conscience is very easy.’

‘I cannot understand that,’ was the disconcerting answer. ‘You do not live with your Queen whom the whole world knows to be a lady of virtue. You pursue a life which cannot give pleasure to your people. It is becoming notorious throughout the country. You have no heir and you know full well that were you to die there would be conflict in this realm.’

‘I have named Prince Arthur as my heir.’

‘A boy who has never seen this country! Do you think the people will accept him? What of Prince John? Were you to die tonight, my lord King, you would be loaded with sin. The friends you choose, the life in which you indulge, these will never bring you an heir. You have taken money from the poor to buy vanities for yourself; you have taxed your people . . .’

‘That I may fight a holy war and set my kingdom in order,’ Richard defended himself.

‘Think on these things, my lord. Life is short and Death is never far away. If you were taken tonight would you care to go before your Maker weighed down with sin as you are?’

The old man had gone as suddenly as he came.

Richard lay staring after him. He thought: It is true. He is a brave man. I could cut out his tongue for what he has said to me this night, but I would not add that sin to all the others. I must rise from this bed. I must mend my ways. I must subdue my inclinations . . . Oh God in Heaven give me another chance.

Within a few days the King’s health had so much improved that he was able to rise from his bed.

He rode to the castle of Poitou.

Berengaria, sitting at her embroidery, her only consolation now that Joanna and the little Cypriot had gone, was wondering whether this was how she would spend the rest of her life. Few came to the castle; the days followed each other one so like the others that she lost count of time. The excitement of Joanna’s romance was over; there was no longer the little Princess to talk to. Sometimes she wondered whether she could ask to go back to her brother’s court. Her father had died some time before and Sancho would welcome her, but that would be to let the whole world know that Richard had deserted her.

And then there came visitors.

She went down to the courtyard to meet them and at the head of them looking as noble as he had that day at the tournament in Pampeluna was Richard himself.

He leaped from his horse and as she would have knelt he lifted her and embraced her.

‘Come into the castle,’ he said. ‘I have much to say to you.’

Bewildered, her heart beating with a wild emotion she was led into her chamber and there he took her hands and said simply: ‘Berengaria, we have been apart too long. It must be so no more.’

She did not understand why he should so suddenly have changed towards her, but what did it matter? He was here and in the future they were to be together. He had said it.

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXI

THE SAUCY CASTLE

So they were together at last and now it was only war which separated them. Richard was constantly engaged in it, for Philip had made the most of his absence and his alliance with John to take possession of much of Normandy. Richard was going to bring it back to the Dukedom.

He was not sorry – war was his life; and the conflict with Philip gave him a satisfaction which Berengaria never could, not even the talents of his beloved Blondel. Philip was the one who dominated his thoughts; and he knew that Philip felt the same about him. Philip might marry and beget children – he was more successful in this field than Richard could be – and yet it was hatred of Richard, his determination to beat him in conflict that was the major force of his life.

Now on the banks of the Seine where the river winds through the valley past the towns of Les Andelys – Petit and Grand – he was building a castle and he was determined that this castle should be the finest, the most beautiful castle in France. It was to be set up in defiance of France; it was to be the defence of Normandy; it would stand there proclaiming that Richard the Lion-hearted was invincible and that Philip of France could never pass beyond that spot to take Normandy. Every moment Richard could spare he was at Les Andelys watching the building of his castle.

Before it was completed, he had named it the Château Gaillard – the Saucy Castle – and saucy it was, perched on a hill overlooking the Seine, commanding the countryside, inviting the French armies to come and see what they would get if they attempted to invade the Normandy of Richard Coeur de Lion.

He had gloated over his prize with its ten feet thick walls except in the keep where their thickness was twelve feet. It was said that it was built on French blood and to give this credence Richard had actually thrown French prisoners from the rock of Les Andelys on to the stones which were the foundations of the castle.

He loved this castle. There was not another to compare with it in France. Men marvelled at it – impregnable, standing at the gates of Normandy; it was built with all the skill gleaned from experience of defensive warfare in Palestine. It was the wonder of the times.

In France a new saying passed into the language: ‘As strong as the Saucy Castle.’

Philip boasted: ‘One day I will take it, were it made of iron.’

Richard responded: ‘I would hold it were it made of butter.’

When the castle had been completed one year Richard celebrated its anniversary with a great feast to which he summoned all his knights and barons.

‘See how beautiful she is, my child of one year old,’ he cried.

He delighted in the castle. He had failed to win Jerusalem but he had built Château Gaillard.

He continued his wars with Philip and so successful was he that the time came when Philip was obliged to sue for peace.

What peace there could be between them would be temporary and both knew it, but Philip was asking for it and Richard laughed to himself to contemplate the humiliation the French King must feel.

‘The King of France believes that a satisfactory peace can only be made if there is a meeting between himself and King Richard,’ was the message Philip sent to him.

A meeting! They had not seen each other since they had parted at Acre. Richard remembered him then – a sick man Philip had been, for it was true that that pernicious climate had impaired his health. His thinning hair, the pallor of his face, the flaking nails . . . he had not been like the arrogant Philip of their youth.

And now . . . what had the years in France done to Philip? All that time when Richard had been imprisoned Philip had been living his luxurious life in France. Nay, he had been fighting, with John as his ally and only those loyal Norman seneschals had kept Normandy for its Duke.

To see Philip again. Yes, he wanted it. He wanted to remember long ago days when they had been young and had meant so much to each other.

He would meet Philip. Where? He, Richard, would choose the place since it was Philip who sued for the meeting. It should be on the Seine with the Saucy Castle as the background of their meeting place. Not too near; he was never going to allow the French very near his darling. But just so that Philip could see those mighty towers and bastions and realise through them the invincible might of Richard of England.

He would go by boat from Gaillard to the meeting place. He would not leave his boat. He would not go too near Philip. He wanted hate to be uppermost not love. Love! They were enemies. It was true, but once there had been love between them, a love which neither of them had been able to forget throughout their lives.

Philip was on horseback close to the banks of the Seine; Richard was seated in his boat.

‘It is long since we met,’ said Philip, and there was a faint tremor in his voice.

‘I remember it well. You were in a sorry state. You had broken your vows; you were creeping back to France.’

‘It was that or death,’ answered Philip.

‘Your vows broken.’

‘My health was broken.’

‘You have recovered now, Philip.’

‘And you look as healthful as ever,’ replied Philip.

‘War suits me, victorious war.’

‘We were born to fight against each other . . . more’s the pity. I would rather be your friend, Richard.’

‘You have said that before.’

‘’Tis true. I remember . . .’

‘It is not good to remember. We have business to talk. You took advantage of my absence. You worked with my enemies against me. You bribed the Emperor to hold me in his fortress. This I can never forget. It has made me your enemy for life.’

‘If we could talk together . . .’

‘We are talking together.’

‘Alone . . .’

Who could trust perfidious Philip? he asked himself and he answered: ‘You could, Richard, as once you did.’

Richard hesitated just for a moment. He thought of past pleasures. Those youthful days when they had ridden together and lain in the shared bed and talked of crusades.

But Philip was King of France, the proven enemy of the King of England. They did not meet now as friends and lovers – though in their hearts they might have been so – they met as the Kings of two countries who must ever be at war with each other.

The Pope’s legate was on his way to mediate between them. Their wars were devastating the land. There must be a pause in their hostilities. There must be a treaty of peace between them.

If we were at peace, thought Philip, we could be friends. Why should we not be? But the needs of France must be his main concern. Private feelings must not come between him and that. And how beautiful was Richard, seated there in his boat, a little arrogant against the background of his Saucy Castle.

They talked of terms. A marriage between a niece of Richard’s and Philip’s son Louis. Her dowry to be Gisors, that important fortress built by William Rufus and which was always a cause of concern to the side which did not own it.

They came to an agreement. The treaty should be drawn up.

‘We shall meet again for the signing,’ said Philip.