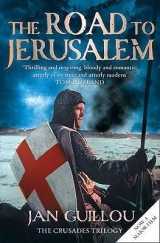

Текст книги "The Road to Jerusalem"

Автор книги: Jan Guillou

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Arn rode a long time across fens and bogs where there was no human dwelling. It had already grown dark by the time he reached the slopes of Billingen. He knew that he needed only to continue north and he would soon come upon the fields of Varnhem, where he would either recognize the way or be able to ask directions. But it was risky to ride in the hills at night, and the sky was overcast, with neither moon nor stars lighting his way. He continued on listlessly for as long as he could see where he was steering Shimal, but he soon had to prepare to stop for the night. It was going to be cold, since he had no sheepskins with him and only a thin cloak, but he took this as only the beginning of the tests and the penance that he knew lay before him. He wanted to suffer much, if only it shortened the time of punishment, so that with God's help he would be able to fulfill his holy vow to fetch Cecilia from Gudhem.

In the dusk he found a little hut where a fire was glowing, and next to it stood a tumbledown stable where a cow lowed restlessly when he approached. He surmised that freed or escaped thralls lived here, but he would rather sleep in their hut than out in the cold woods.

He boldly entered the hut to ask for shelter for the night. He now feared nothing, since he could imagine nothing worse than what had already befallen him, and he had silver to offer as payment, which was the honorable and Christian thing to do instead of showing his sword as reason enough for his visit.

Yet he was somewhat shocked by the stooped old woman who sat by the fire stirring a kettle. She spoke in a croaking voice and greeted him not at all politely but with scorn and words that he didn't understand, saying that such as he should fear the dark, while such as she was a friend of the dark.

Arn answered her calmly and explained that he simply sought shelter for the night so that his horse might not be injured by continuing over the mountain in the dark. He added that he would pay her well for this service. When she didn't answer he went outside and removed the saddle from Shimal and put him in the stable with the lone skinny cow. When he came back to the hut he unbuckled his sword and tossed it on an empty bunk as a sign that this was where he intended to sleep. Then he pulled a little three-legged stool up to the fire and sat down to warm his hands.

The old woman peered at him suspiciously for a long while before she finally asked if he was someone who had a right to bear a sword, or one who bore a sword anyway. Arn replied that there were various opinions on that matter, but that she in any case had nothing to fear from his sword. As if to calm her he took out the little leather purse Eskil had given him when he left and fished out two silver coins, which he put down next to the fireplace so that they were lit by the glow. She picked up a coin and bit it, which Arn found incomprehensible, as he could not understand how anyone could doubt his word or good intentions. But she seemed satisfied with what her few teeth told her and asked if like all the others he had come here to find out what awaited him in the future. Arn replied that the future lay in God's hands, and no one else could predict it. She laughed so loud at this that she revealed her gaping mouth with only a few blackened teeth. She stirred her pot in silence for a while and then asked whether he would like some of the soup. Arn politely declined. He was already resigned to a long penance on bread and water.

"In what lies ahead for you in life I see three things, boy," she said suddenly, as if her alleged vision was pushing forward despite Arn's lack of interest. "I see two shields; would you like to know what I see?" she went on, squeezing both eyes shut as if to look inside herself. Arn's curiosity was already aroused, and maybe she saw that too behind her closed eyelids.

"What shields do you see?" he asked, sure that she would now say something foolish.

"One shield has three golden crowns against the sky and the other shield has a lion," she replied in a new singsong tone, her eyes still shut.

Arn was dumbstruck. He couldn't conceive of how a solitary old woman far out in the wilderness could have the slightest idea of such things, and even less that she could know who he was, or had been able to guess anything by looking at his clothes. He remembered a story to which he had given little credence, a story told to him by Knut, who said that his father Erik Jedvardsson, out on a crusade, had received a prophecy about the three crowns. But that had happened far away, on the other side of the Eastern Sea.

"What is the third thing you see?" he asked cautiously.

"I see a cross and I hear words with the cross, and what I hear are the words 'In this sign shalt thou conquer,'" she continued in her singsong way, without any expression on her face or opening her eyes.

Arn thought first that she must have been more sharp-eyed than he realized and read the Latin inscription on the hilt of his sword.

"You mean, 'In hoc signo vinces'?" he asked to test her. But she merely shook her head as if the Latin words meant nothing to her.

"Do you see a woman in my future?" he asked with some trepidation, which could probably be heard in his voice.

"You will get your woman!" she shrieked in a shrill voice and opened her eyes, staring wildly at him. "But nothing will be as you think, nothing!"

She laughed at him in her hoarse, cackling voice, but it was as if her mood had been broken and he could no longer get a sensible word out of her. Soon he gave up and lay down to sleep on the bunk where he'd tossed his sword. He wrapped his mantle around him, turned to the wall, and closed his eyes, but he couldn't fall asleep. He tossed and turned for a while, thinking of what the old woman had said, and found that it was both true and meager. The fact that she could see the Folkung and Erik clans inside him was strange, he had to admit. But she hadn't said anything that he didn't know for himself. That he would have Cecilia back was reassuring, and that was what he believed. At last he must have fallen asleep.

When he awoke at dawn she was gone, but Shimal was in his place out in the little stable and neighed a welcome as if nothing had happened.

It was after midday when he rode in through the gate of Varnhem cloister, and all the familiar smells washed over him from the gardens and Brother Rugiero's cookhouse. His arrival was expected but it also aroused some commotion, and two brothers ran to meet him; one led Shimal away and the other escorted him in silence to the lavatorium and then pointed to his clothes. When Arn did not understand, the brother said peevishly that since he was excommunicated he could not be spoken to before he at least washed up a bit. After that he would be given a lay brother's clothing.

Arn washed himself long and thoroughly and trimmed his long hair as he said the appropriate prayers. In his lay brother's attire, which felt oddly familiar, he then reported to Father Henri at his favorite place in the arcade. Father Henri looked at him with much sternness but also love. Then he sighed heavily and took out his prayer stole and motioned for Arn to prepare himself for his confession. Arn fell to his knees and prayed to Holy Saint Bernard to give him the strength and honesty to perform this confession, which would not be easy to make.

King Knut Eriksson arrived at Arnäs with a royal retinue and Birger Brosa. They were many men and it would take some time to see to it that they were all properly quartered. But they were expected, and it was said in the nearest village that the many hungry and weary men would be received well.

Birger Brosa was impatient for them to hold a council as soon as possible instead of pouring ale into themselves first. Even with King Knut present, arrangements were made immediately as Birger Brosa desired, and those involved with the matter gathered in the hall of the longhouse with only a little ale in their bodies.

They prayed first for the Lord to bless this meeting, and that wise words would be spoken here and not foolish ones. Those phrases sounded so awkward and almost simpleminded that Arn's absence was felt like a gust of wind passing through the entire hall. But the question of Arn was only one of the many topics they had to discuss.

Birger Brosa was the one who took the floor when they had settled down to begin the council, and he believed that the first concern had to be the landsting in Western Götaland, since much depended on Knut obtaining his second crown, and the sooner the better. No one was opposed.

They then spent a good while deliberating what messages should be sent and how knowledge of the ting should be disseminated best and as rapidly as possible. Since nothing that was said on this matter was either new or unfamiliar, this question was also swiftly resolved.

According to Birger Brosa, the next item involved the best way for Knut, once he was elected king, to proceed in order to lift the shame that had befallen the Folkungs with an excommunicated member of the clan. This, said Birger Brosa, was a matter that Knut himself must address.

Knut Eriksson began by assuring them that Arn, as they all knew, was his dearest friend, and that Arn had also done him very great services that had to be reciprocated. In addition, all the good that the Eriks and the Folkungs could do each other had to take precedence above all else. After saying this and more in the same vein, he got to the heart of the matter.

As far as he understood it, an archbishop could without difficulty annul the excommunication ordered by Bishop Bengt in Skara. The problem was that the archbishop had left his see and no one knew where he was. At least he was not in Linköping, and it would be unfortunate if he had been seized by the Sverker clan, but he was not in Svealand either. Knut's informants would have heard of this, because an archbishop was not that easy to hide.

Now, these men of God could sometimes prove obstinate. So even if they got hold of the missing archbishop, it was not easy to predict how things would turn out if his king required a decision on matters over which the church claimed authority. Priests could always be threatened, that was clear. The clergy were cov etous and jealous of their lands, and they strove to gain new gifts of property, which could sometimes make them soft in negotiations. Yet it was impossible to say anything more about this before two things had occurred. First, Knut had to be elected king in Western Götaland as well, just as his dear kinsman and wise adviser Birger Brosa had said. Then he could negotiate from a position of strength with the archbishop. Besides, the prelate must be fished out from his hiding place before they would have a sense of what stand he might take.

Magnus sadly agreed and confirmed that in this matter they could go no further just now. But he wanted to move on to the next most important concern. With such cases undertaken by the church that had to be documented and sent to Rome, much was unclear for ordinary Christian folk. What they knew was that such complicated negotiations could take time. So they had to think about Arn and Cecilia's child. According to what the womenfolk said, Cecilia would give birth to Arn's son sometime after midwinter. And the Sverker hag at Gudhem would see to it that the child was cast out as soon as possible; they could certainly count on that. So what should be done?

Knut Eriksson spoke first, saying that if he was quickly elected king in Western Götaland, he would not without a certain satisfaction engage in a tussle with the Sverker hag at Gudhem. She would be made to understand that she no longer inhabited a safe vessel, which should make her vulnerable in negotiations.

Birger Brosa frowned. First, he pointed out, Knut should think carefully before he inflamed the church as his father had done. It would be better to take another tack, trying to persuade by hook or by crook, rather than using threats. Second, no child born of an unlawful bed could be held in a cloister. That would be too much to ask, and no one would be served by the malicious gossip that would result from such an eventuality. With that, the question seemed quite straightforward: Who would take care of Arn Magnusson's son? And for that matter, did unlawful sons become lawful when a marriage was later entered into?

Eskil had the answers to both these questions. To make arrangements so that Arn and Cecilia's child—whether it was a son or not, and he didn't understand how they all could be so certain of that—ended up with Algot Pålsson was not a good idea. Algot was already reported to have muttered that instead of a son-in-law he was going to have a bastard in his house. Such words did not testify to a good attitude. So the child would have to be cared for by the Folkung clan.

And as far as the other matter was concerned, whether unlawful children could become lawful, the answer was simple. If the excommunication could be lifted and the wedding ale that was envisioned between Arn and Cecilia celebrated, then all would be in its proper order once again.

Birger Brosa then said thoughtfully that since he too had infant children and a mother and two extra wet nurses to take care of them, it seemed best if the boy was allowed to come to Bjälbo. No one objected to that.

The last question they had to contend with was of lesser importance but still as vexing as a chafed foot. Algot Pålsson had not only grumbled about a bastard in the house, he had also complained out loud and bitterly that a son of Arnäs had so mucked up a good business deal that it was obvious it would come to naught. Algot of course was no dangerous foe, and he would think twice before drawing a sword against the Folkungs. Still, it was ill advised for him to be grumbling publicly like that.

Magnus replied with some melancholy that this was merely a matter of the priests' written report to Rome, and all the associated complications could take a great deal of time. If things moved quickly, then all would be arranged as it was intended from the start. But if the matter dragged on for several years, which such things had been known to do, then the situation would be much worse. In that case, Magnus thought, they ought to make the same bargain as originally intended, although with Katarina as bride and Eskil as bridegroom. For Katarina had just been released from the convent in Gudhem.

A sense of gloom settled over the table. Everyone knew that it was Katarina who was the actual cause of this trouble that had now befallen not only Arn and Cecilia but the whole Folkung clan. It seemed wrong, Eskil said with a sigh, to reward Katarina so highly for her malicious deed.

Birger Brosa responded coldly that it sounded like a wise thing to do, and that young Eskil ought to realize that they were speaking only of business, and not of emotions. So if Arn was not released, Eskil must be prepared to go to the bridal bed with a woman to whom he might not care to turn his back, for fear of inviting a dagger.

There the matter was left. At this table the issues were business and the struggle for power, and love by no means had the final word.

Father Henri had not made the slightest move to give Arn absolution for his sins as he listened to his confession. Nor had Arn expected that he would, because he was excommunicated, and not even a prior like Father Henri could annul an excommunication. In brief Father Henri had explained the nature of Arn's sin and then sent him to a cell for meditation on bread and water and all the other acts of penance he might expect.

During his time in the base world Arn had managed to commit three grave sins. First, he had killed two drunken peasants; second, drunk himself, he'd had carnal relations with Katarina; and third, he'd had carnal relations with Cecilia.

Of these three sins the first two had been forgiven so easily and simply that Arn himself had wondered about it. But the third sin, which arose because he had carnal relations with Cecilia as well, the woman he loved and wanted to live with as man and wife forever, had been such a grave sin that he had been excommunicated, dragging her to her own ruin. It was incomprehensible. Killing two men was nothing, and having carnal relations with a woman he didn't love was nothing. But doing the same thing with a woman he loved above all else on earth, as the Holy Scriptures described love—that was the gravest of sins.

They had sent him the text of the law from the archive at Varnhem, and in the text everything stood clear and inexorable. In the archive were kept only such law texts as the church itself had pushed through, of course; everything else, such as single combat, defamation, and monetary fines if one slew someone else's thralls or stole someone else's livestock, were of minor interest to the church.

But the law that Arn had broken was something that the church had fought for and ultimately pushed through. In the text of the marriage act for Western Götaland it said:

If a man lies with his daughter, the case shall be re ported in writing and sent to Rome. If father and son own the same woman, if two brothers own the same woman, if two brothers' sons own the same woman, if mother and daughter own the same man, if two sisters own the same man, if two sisters' daughters own the same man, it is an abomination.

So it was written. The passage was beautifully printed in Latin while the subsequent translation into the vernacular was written in cursive. Arn had no difficulty recognizing the prohibition, for he knew it had been taken from the Pentateuch of Moses in the Holy Scriptures.

But there were all sorts of senseless and peculiar prohibitions to be found in the Holy Scriptures, and everything that Arn thought he knew about how to interpret such things now fell flat on the ground. That it was abomination if someone lay with his daughter was easy to understand. But it was impossible to comprehend how lying with Katarina once when he was drunk could be considered the same as what he and Cecilia had done together out of love—while physically there might be a resemblance, there was none in spirit.

Arn brooded for a long time over God's law. He tested his theological reasoning on the regulations from the Old Testament, comparing his crime to similar prohibitions such as wearing clothing of a certain color during the month of mourning or having one's hair cut in a certain way. But it made no difference and all such ruminations were useless because the same prohibition had been written into the laws of Western Götaland. He remembered well the respect that his kinsmen had displayed when Judge Karle recited the law regarding slander. There was so little room for interpretation that his own father had been prepared to die as prescribed by law.

But according to this law, he had committed a crime that was equivalent to the abomination of lying with his own daughter.

Yet it was God's holy church that would judge. And among men of God the thoughts and intentions behind a crime were given different consideration than among the West Goths.

No matter how Arn twisted and turned this question, everything finally came down to what Father Henri would decide. For it was clear that Arn would not be judged by any ting; he snorted at the thought of how easily he would be able to defend himself either with a sword or a countless number of Folkung oath-swearers.

He would be judged by God's holy church, and that meant there was at least a reasonable chance of weighing good against evil. So he hovered between hope and despair.

His hope grew even greater when a brother came to fetch him to a meeting with Archbishop Stéphan. Arn had no idea that the archbishop was at Varnhem, and at first he thought that it might have something to do with his own case, since the archbishop had once told Arn that he would always have a friend out there in the other world, a friend who would stand by him, and who was none other than the archbishop himself.

Arn hurried to the arcade where he found Father Henri in his usual place, and to his joy also Archbishop Stéphan. He fell to his knees at once to kiss the archbishop's hand and did not take a seat until he was told to do so.

Yet it was not kindness that Arn saw in the archbishop's eyes as the prelate studied him for a while in silence. And with that, Arn felt the warmth of his hope swiftly cool.

"These are no small lapses that you have managed during your brief time out there in the base world," the archbishop began at last. He sounded very stern, and Father Henri sitting next to him did not look at Arn but seemed to be examining his own sandals.

"You know very well," continued the archbishop in the same stern tone, "that the power of the church must not be intermingled with earthly power. And yet that is just what you have done, and you have now placed me in quite a quandary. With open eyes you did this, and even with some cunning."

The archbishop paused as if to hear what excuses or explanations the young man might offer. But Arn, who had been completely prepared to take part in a discussion of his carnal sins, now felt utterly bewildered. He didn't understand what the archbishop was talking about, and he said so, apologizing for his stupidity. The archbishop then heaved a great sigh, but Arn caught the trace of a smile on the face of the venerable man, as if he did indeed believe Arn's plea of ignorance.

"You can't have such a short memory that you've forgotten that we saw each other not so long ago up in Östra Aros, can you?" asked the archbishop in a voice that was both agreeable and harsh.

"No, Your Excellency, but I don't understand how I then should have sinned," replied Arn uncertainly.

"That's remarkable!" snorted the archbishop. "You show up with a man in tow who was one of those contenders for the crown who are unfortunately so numerous in this part of the world. You join in his request that I in some way should make haste and practically crown him on the spot. When I then refuse this request, for reasons which you surely knew in advance, what do you do then? You fairly fool the robe off me and leave me standing with my bare rump showing, that's what you do. And since you are one of us, and will remain so forever, both Father Henri and I have conducted lengthy and sincere deliberations, trying to decide what you were thinking when you acted as you did."

"I wasn't thinking about much at all," Arn replied, since it now began to dawn on him what they were talking about. "As Your Excellency so truly says, I did know that there could be no talk of the church immediately announcing its support of Knut Eriksson. But I found no fault in the fact that Your Excellency himself should present this view of the matter to my friend. And that was what happened."

"Well, but then, what were you thinking later when you staged the spectacle that caused the stupid crowd outside to believe that I had anointed and crowned the cunning devil?"

"I didn't understand much of what went on out there," Arn replied in shame. "We hadn't talked about what would happen if Your Excellency should refuse to approve Knut Eriksson's wishes. He thought he was presenting a simple request, and I couldn't persuade him otherwise, since he felt that he was already king. So I thought that Your Excellency would have to explain the whole matter, just as you did."

"Yes, yes, yes!" snapped the archbishop, waving his hand impatiently. "You already said that. But now I'm wondering about what happened after I put the scamp in his place!"

"Then he wanted me to ask Your Excellency whether the two of us might have the honor of receiving Holy Communion from Your Excellency in person at the next day's mass. I found nothing un-Christian in such a request. But I didn't know that—"

"So the two of you hadn't talked about that beforehand? You didn't know a thing about what trickery would follow?" the archbishop interrupted him sternly.

"No, Your Excellency, I didn't know," replied Arn, shamefaced. "My friend had not expected that his first request would be refused at once. But the request to receive Holy Communion was not something we had spoken about at all."

The two older men now looked intently at Arn, who did not avert his eyes or show the least hesitation, since what he'd said was entirely true, as surely as if he were under the oath of confession.

Father Henri cleared his throat lightly and looked up at the archbishop, who met his gaze and nodded in agreement. They had drawn definite conclusions about something they had discussed in advance, that much Arn could see.

"Well, well, my young friend, sometimes you are more than a little childish, I must say," said the archbishop in a different and much friendlier tone of voice. "You took your sword with you and handed it to me, and you knew that I could do nothing but bless it, and you were both dressed for battle. What was your intention?"

"My sword is sanctified, and I have never broken its oath. I felt pride when I could bear such a sacred sword to Your Excellency. I also thought that you, Your Excellency, would feel the same way, since the sanctification of the sword occurred right here with the Cistercians," replied Arn.

"And you had no idea how your friend, Knut Eriksson, was going to exploit the occasion?" asked the archbishop with a weary smile, shaking his head at the same time.

"No, Your Excellency, but afterward I did understand—"

"Afterward there was a great commotion all over Svealand!" snapped the archbishop. "The rumors made it look as though I, from my see, had blessed the sword that was supposed to have murdered King Karl Sverkersson, as if I furthermore had blessed Knut Eriksson and practically anointed and crowned him. Since then I haven't had a peaceful moment, for now all the petty kings and half kings and king pretenders are after me! I'm going to be leaving the country for a while; that's why I'm here and not for your sake, as you may have thought. However, I believe what you've said about everything that happened up in Östra Aros, and you have my forgiveness."

Arn fell to his knees before the archbishop and kissed his hand again. He thanked him for showing such forgiving kindness, no matter how undeserved, since ignorance was not a sufficient defense. In a brief moment of happiness Arn imagined that everything was now over, that his sin was not having lain with Cecilia in love but rather that he had sinned by helping Knut Eriksson, who for dishonest purposes had made a fool of the archbishop himself.

But it was not over. When Arn stood up at the archbishop's kind exhortation and sat down in his place facing the two old friends, he received his judgment.

"Listen to me carefully," said the archbishop. "Your sins are forgiven with regard to the trick you played on your own archbishop. But you have broken God's law by having lain with two women who are sisters, and for such a sin, which is abomination, there is no easy grace. It would be normal for us to sentence you to penance for the rest of your life. But we shall show you mercy because we believe that it is the intention of the Lord. Your penance you shall serve for half a lifetime, twenty years, and the same applies to your mistress. You shall serve your penance as a Knight Templar of the Lord, and your name henceforth shall be Arn de Gothia and nothing else. Go now to your penance, and may the Lord guide your steps and your sword, and may His Grace shine upon you. Brother Guilbert will explain everything to you in more detail. I will be leaving now, but we will see each other on the road to Rome, which is where you must go first."

Arn's head was spinning. He realized that he had been shown mercy, and yet not. For half a lifetime was longer than he had been alive, and he could not even imagine himself as an old man, at the age of thirty-seven, when his sins would be absolved. He gave Father Henri a look of entreaty though without saying a word, and it seemed as though he could not bring himself to leave before Father Henri had said something to him.

"The road to Jerusalem took many turns in the beginning, my dear, dear Arn," Father Henri said quietly. "But this was God's will, of that we are both convinced. Go now in peace!"

When Arn with head bowed and almost staggering had left them, the two men sat there for a long time, becoming entangled in an ever deeper conversation about God's will. Because it was clear to them both that God's intention was to send yet another great warrior to His Holy Army.

But what if Knut Eriksson had become king somewhat earlier, and Arn and Cecilia had already been blessed as man and wife? What if Cecilia, who seemed to be as equally good-hearted and childish as Arn, had not visited her sister Katarina? What if Prioress Rikissa had not been of the Sverker clan and had not used her power and great determination to instigate this whole disturbance?

If all this and much else had not happened, God's Holy Army would have been missing one warrior. On the other hand, the philosopher had already shown that this type of reasoning was never tenable. If this were not so, the archbishop would have been a horse. But God had clearly shown His will, and before His will they must bow.

Brother Guilbert proceeded cautiously with Arn over the next few days as he set about the task of making him understand what now and for a long time to come would be his fate. He did not allow Arn to start talking about his punishment or all that he would have to leave behind; he kept to the practical matters.

Arn would ride with Archbishop Stéphan to Rome, but there their ways would part, since the archbishop had things to work out with Pope Alexander III, while Arn would report to the castle of the Knights Templar in Rome, which was the largest such castle in the world. That was because it was in Rome that all who sought admittance to the order would be either approved or rejected. Naturally there were many who felt themselves called to fight in God's Holy Army, not least since they would thereby do penance for all their sins and gain entry to Heaven if they died with sword in hand. Consequently it was only one out of ten aspirants who were accepted after testing.