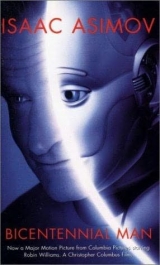

Текст книги "The Bicentennial Man and Other Stories"

Автор книги: Isaac Asimov

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

3.

Anthony was waiting on the roof reception area to greet the incoming expert. Not he by himself, of course. He was part of a sizable delegation-the size itself a rather grim indication of the desperation to which they had been reduced-and he was among the lower echelons. That he was there at all was only because it was he who had made the original suggestion.

He felt a slight, but continuing, uneasiness at the thought of that. He had put himself on the line. He had received considerable approval for it, but there had been the faint insistence always that it was his suggestion; and if it turned out to be a fiasco, every one of them would move out of the line of fire and leave him at point-zero.

There were occasions, later, when he brooded over the possibility that the dim memory of a brother in homology had suggested his thought. That might have been, but it didn't have to be. The suggestion was so sensibly inevitable, really, that surely he would have had the same thought if his brother had been something as innocuous as a fantasy writer, or if he had had no brother of his own.

The problem was the inner planets-The Moon and Mars were colonized. The larger asteroids and the satellites of Jupiter had been reached, and plans were in progress for a manned voyage to Titan, Saturn's large satellite, by way of an accelerating whirl about Jupiter. Yet even with plans in action for sending men on a seven-year round trip to the outer Solar System, there was still no chance of a manned approach to the inner planets, for fear of the Sun.

Venus itself was the less attractive of the two worlds within Earth's orbit. Mercury, on the other hand

Anthony had not yet joined the team when Dmitri Large (he was quite short, actually) had given the talk that had moved the World Congress sufficiently to grant the appropriation that made the Mercury Project possible.

Anthony had listened to the tapes, and had heard Dmitri's presentation. Tradition was firm to the effect that it had been extemporaneous, and perhaps it was, but it was perfectly constructed and it held within it, in essence, every guideline followed by the Mercury Project since.

And the chief point made was that it would be wrong to wait until the technology had advanced to the point where a manned expedition through the rigors of Solar radiation could become feasible. Mercury was a unique environment that could teach much, and from Mercury's surface sustained observations could be made of the Sun that could not be made in any other way.

– Provided a man substitute– a robot, in short– could be placed on the planet.

A robot with the required physical characteristics could be built. Soft landings were as easy as kiss-my-hand. Yet once a robot landed, what did one do with him next?

He could make his observations and guide his actions on the basis of those observations, but the Project wanted his actions to be intricate and subtle, at least potentially, and they were not at all sure what observations he might make.

To prepare for all reasonable possibilities and to allow for all the intricacy desired, the robot would need to contain a computer (some at Dallas referred to it as a "brain," but Anthony scorned that verbal habit– perhaps because, he wondered later, the brain was his brother's field) sufficiently complex and versatile to fall into the same asteroid with a mammalian brain.

Yet nothing like that could be constructed and made portable enough to be carried to Mercury and landed there– or if carried and landed, to be mobile enough to be useful to the kind of robot they planned. Perhaps someday the positronic-path devices that the roboticists were playing with might make it possible, but that someday was not yet.

The alternative was to have the robot send back to Earth every observation it made the moment it was made, and a computer on Earth could then guide his every action on the basis of those observations. The robot's body, in short, was to be there, and his brain here.

Once that decision was reached, the key technicians were the telemetrists and it was then that Anthony joined the Project. He became one of those who labored to devise methods for receiving and returning impulses over distances of from 50 to 40 million miles, toward, and sometimes past, a Solar disk that could interfere with those impulses in a most ferocious manner.

He took to his job with passion and (he finally thought) with skill and success. It was he, more than anyone else, who had designed the three switching stations that had been hurled into permanent orbit about Mercury– the Mercury Orbiters. Each of them was capable of sending and receiving impulses from Mercury to Earth and from Earth to Mercury. Each was capable of resisting, more or less permanently, the radiation from the Sun, and more than that, each could filter out Solar interference.

Three equivalent Orbiters were placed at distance of a little over a million miles from Earth, reaching north and south of the plane of the Ecliptic so that they could receive the impulses from Mercury and relay them to Earth-or vice versa-even when Mercury was behind the Sun and inaccessible to direct reception from any station on Earth ' s surface.

Which left the robot itself; a marvelous specimen of the roboticists' and telemetrists' arts in combination. The most complex of ten successive models, it was capable, in a volume only a little over twice that of a man and five times his mass, of sensing and doing considerably more than a man– if it could be guided.

How complex a computer had to be to guide the robot made itself evident rapidly enough, however, as each response step had to be modified to allow for variations in possible perception. And as each response step itself enforced the certainty of greater complexity of possible variation in perceptions, the early steps had to be reinforced and made stronger. It built itself up endlessly, like a chess game, and the telemetrists began to use a computer to program the computer that designed the program for the computer that programmed the robot-controlling computer.

There was nothing but confusion. The robot was at a base in the desert spaces of Arizona and in itself was working well. The computer in Dallas could not, however, handle him well enough; not even under perfectly known Earth conditions. How then

Anthony remembered the day when he had made the suggestion. It was on 7-4-553. He remembered it, for one thing, because he remembered thinking that day that 7-4 had been an important holiday in the Dallas region of the world among the pre-Cats half a millennium before– well, 553 years before, to be exact.

It had been at dinner, and a good dinner, too. There had been a careful adjustment of the ecology of the region and the Project personnel had high priority in collecting the food supplies that became available-so there was an unusual degree of choice on the menus, and Anthony had tried roast duck.

It was very good roast duck and it made him somewhat more expansive than usual. Everyone was in a rather self-expressive mood, in fact, and Ricardo said, "We'll never do it. Let's admit it. We'll never do it."

There was no telling how many had thought such a thing how many times before, but it was a rule that no one said so openly. Open pessimism might be the final push needed for appropriations to stop (they had been coming with greater difficulty each year for five years now) and if there were a chance, it would be gone.

Anthony, ordinarily not given to extraordinary optimism, but now reveling over his duck, said, "Why can't we do it? Tell me why, and I'll refute it."

It was a direct challenge and Ricardo's dark eyes narrowed at once. "You want me to tell you why?"

"I sure do." Ricardo swung his chair around, facing Anthony full. He said, "Come on, there's no mystery. Dmitri Large won't say so openly in any report, but you know and I know that to run Mercury Project properly, we'll need a computer as complex as a human brain whether it's on Mercury or here, and we can't build one. So where does that leave us except to play games with the World Congress and get money for make-work and possibly useful spin-offs?"

And Anthony placed a complacent smile on his face and said, "That's easy to refute. You've given us the answer yourself." (Was he playing games? Was it the warm feeling of duck in his stomach? The desire to tease Ricardo?…Or did some unfelt thought of his brother touch him? There was no way, later, that he could tell.)

"What answer?" Ricardo rose. He was quite tall and unusually thin and he always wore his white coat unseamed. He folded his arms and seemed to be doing his best to tower over the seated Anthony like an unfolded meter rule. "What answer?"

"You say we need a computer as complex as a human brain. All right, then, we'll build one."

"The point, you idiot, is that we can't-"

"We can't. But there are others."

"What others?"

"People who work on brains, of course. We're just solid-state mechanics. We have no idea in what way a human brain is complex, or where, or to what extent. Why don't we get in a homologist and have him design a computer?" And with that Anthony took a huge helping of stuffing and savored it complacently. He could still remember, after all this time, the taste of the stuffing, though he couldn't remember in detail what had happened afterward.

It seemed to him that no one had taken it seriously. There was laughter and a general feeling that Anthony had wriggled out of a hole by clever sophistry so that the laughter was at Ricardo's expense. (Afterward, of course, everyone claimed to have taken the suggestion seriously.)

Ricardo blazed up, pointed a finger at Anthony, and said, "Write that up. I dare you to put that suggestion in writing." (At least, so Anthony's memory had it. Ricardo had, since then, stated his comment was an enthusiastic "Good ideal Why don't you write it up formally, Anthony?")

Either way, Anthony put it in writing.

Dmitri Large had taken to it. In private conference, he had slapped Anthony on the back and had said that he had been speculating in that direction himself– though he did not offer to take any credit for it on the record. (Just in case it turned out to be a fiasco, Anthony thought.)

Dmitri Large conducted the search for the appropriate homologist. It did not occur to Anthony that he ought to be interested. He knew neither homology nor homologists-except, of course, his brother, and he had not thought of him. Not consciously.

So Anthony was up there in the reception area, in a minor role, when the door of the aircraft opened and several men got out and came down and in the course of the handshakes that began going round, he found himself staring at his own face.

His cheeks burned and, with all his might, he wished himself a thousand miles away.

4.

More than ever, William wished that the memory of his brother had come earlier. It should have…Surely it should have.

But there had been the flattery of the request and the excitement that had begun to grow in him after a while. Perhaps he had deliberately avoided remembering.

To begin with, there had been the exhilaration of Dmitri Large coming to see him in his own proper presence. He had come from Dallas to New York by plane and that had been very titillating for William, whose secret vice it was to read thrillers. In the thrillers, men and women always traveled mass-wise when secrecy was desired. After all, electronic travel was public property– at least in the thrillers, where every radiation beam of whatever kind was invariably bugged.

William had said so in a kind of morbid half attempt at humor, but Dmitri hadn't seemed to be listening. He was staring at William's face and his thoughts seemed elsewhere. "I'm sorry," he said finally. "You remind me of someone."

(And yet that hadn't given it away to William. How was that possible? he had eventual occasion to wonder.)

Dmitri Large was a small plump man who seemed to be in a perpetual twinkle even when he declared himself worried or annoyed. He had a round and bulbous nose, pronounced cheeks, and softness everywhere. He emphasized his last name and said with a quickness that led William to suppose he said it often, "Size is not all the large there is, my friend."

In the talk that followed, William protested much. He knew nothing about computers. Nothing! He had not the faintest idea of how they worked or how they were programmed.

"No matter, no matter," Dmitri said, shoving the point aside with an expressive gesture of the hand. "We know the computers; we can set up the programs. You just tell us what it is a computer must be made to do so that it will work like a brain and not like a computer."

"I'm not sure I know enough about how a brain works to be able to tell you that, Dmitri," said William.

"You are the foremost homologist in the world," said Dmitri. "I have checked that out carefully." And that disposed of that.

William listened with gathering gloom. He supposed it was inevitable. Dip a person into one particular specialty deeply enough and long enough, and he would automatically begin to assume that specialists in all other fields were magicians, judging the depth of their wisdom by the breadth of his own ignorance…And as time went on, William learned a great deal more of the Mercury Project than it seemed to him at the time that he cared to.

He said at last, "Why use a computer at all, then? Why not have one of your own men, or relays of them, receive the material from the robot and send back instructions."

"Oh, oh, oh," said Dmitri, almost bouncing in his chair in his eagerness. "You see, you are not aware. Men are too slow to analyze quickly all the material the robot will send back– temperatures and gas pressures and cosmic– ray fluxes and Solar-wind intensities and chemical compositions and soil textures and easily three dozen more items– and then try to decide on the next step. A human being would merely guide the robot, and ineffectively; a computer would be the robot.

"And then, too," he went on, "men are too fast, also. It takes radiation of any kind anywhere from ten to twenty-two minutes to take the round trip between Mercury and Earth, depending on where each is in its orbit. Nothing can be done about that. You get an observation, you give an order, but much has happened between the time the observation is made and the response returns. Men can't adapt to the slowness of the speed of light, but a computer can take that into account…Come help us, William."

William said gloomily, "You are certainly welcome to consult me, for what good that might do you. My private TV beam is at your service."

"But it's not consultation I want. You must come with me."

"Mass-wise?" said William, shocked.

"Yes, of course. A project like this can't be carried out by sitting at opposite ends of a laser beam with a communications satellite in the middle. In the long run, it is too expensive, too inconvenient, and, of course, it lacks all privacy-"

It was like a thriller, William decided. "Come to Dallas," said Dmitri, "and let me show you what we have there. Let me show you the facilities. Talk to some of our computer men. Give them the benefit of your way of thought."

It was time, William thought, to be decisive. "Dmitri," he said, "I have work of my own here. Important work that I do not wish to leave. To do what you want me to do may take me away from my laboratory for months."

"Months!" said Dmitri, clearly taken aback. "My good William, it may well be years. But surely it will be your work."

"No, it will not. I know what my work is and guiding a robot on Mercury is not it."

"Why not? If you do it properly, you will learn more about the brain merely by trying to make a computer work like one, and you will come back here, finally, better equipped to do what you now consider your work. And while you're gone, will you have no associates to carry on? And can you not be in constant communication with them by laser beam and television? And can you not visit New York on occasion? Briefly."

William was moved. The thought of working on the brain from another direction did hit home. From that point on, he found himself looking for excuses to go-at least to visit-at least to see what it was all like…He could always return.

Then there followed Dmitri's visit to the ruins of Old New York, which he enjoyed with artless excitement (but then there was no more magnificent spectacle of the useless gigantism of the pre-Cats than Old New York).William began to wonder if the trip might not give him an opportunity to see some sights as well.

He even began to think that for some time he had been considering the possibility of finding a new bedmate, and it would be more convenient to find one in another geographical area where he would not stay permanently.

– Or was it that even then, when he knew nothing but the barest beginning of what was needed, there had already come to him, like the twinkle of a distant lightning flash, what might be done

So he eventually went to Dallas and stepped out on the roof and there was Dmitri again, beaming. Then, with eyes narrowing, the little man turned and said, "I knew-What a remarkable resemblance!"

William's eyes opened wide and there, visibly shrinking backward, was enough of his own face to make him certain at once that Anthony was standing before him.

He read very plainly in Anthony's face a longing to bury the relationship. All William needed to say was "How remarkable!" and let it go. The gene patterns of mankind were complex enough, after all, to allow resemblances of any reasonable degree even without kinship.

But of course William was a homologist and no one can work with the intricacies of the human brain without growing insensitive as to its details, so he said, "I'm sure this is Anthony, my brother."

Dmitri said, "Your brother?"

"My father," said William, "had two boys by the same woman-my mother. They were eccentric people."

He then stepped forward, hand outstretched, and Anthony had no choice but to take it…The incident was the topic of conversation, the only topic, for the next several days.

5.

It was small consolation to Anthony that William was contrite enough when he realized what he had done.

They sat together after dinner that night and William said, "My apologies. I thought that if we got the worst out at once that would end it. It doesn't seem to have done so. I've signed no papers, made no formal agreement. I will leave."

"What good would that do?" said Anthony ungraciously. "Everyone knows now. Two bodies and one face. It's enough to make one puke."

"If I leave-"

"You can't leave. This whole thing is my idea."

"To get me here?" William's heavy lids lifted as far as they might and his eyebrows climbed.

"No, of course not. To get a homologist here. How could I possibly know they would send you?"

"But if I leave-"

"No. The only thing we can do now is to lick the problem, if it can be done. Then-it won't matter." (Everything is forgiven those who succeed, he thought.)

"I don't know that I can-"

"We'll have to try. Dmitri will place it on us. It's too good a chance. You two are brothers," Anthony said, mimicking Dmitri's tenor voice, "and understand each other. Why not work together?" Then, in his own voice, angrily, "So we must. To begin with, what is it you do, William? I mean, more precisely than the word 'homology' can explain by itself."

William sighed. "Well, please accept my regrets…I work with autistic children."

"I'm afraid I don't know what that means."

"Without going into a long song and dance, I deal with children who do not reach out into the world, do not communicate with others, but who sink into themselves and exist behind a wall of skin, somewhat unreachably. I hope to be able to cure it someday."

"Is that why you call yourself Anti-Aut?"

"Yes, as a matter of fact."

Anthony laughed briefly, but he was not really amused.

A chill crept into William's manner. "It is an honest name."

"I'm sure it is," muttered Anthony hurriedly, and could bring himself to no more specific apology. With an effort, he restored the subject, " And are you making any progress?"

"Toward the cure? No, so far. Toward understanding, yes. And the more I understand-" William's voice grew warmer as he spoke and his eyes more distant. Anthony recognized it for what it was, the pleasure of speaking of what fills one's heart and mind to the exclusion of almost everything else. He felt it in himself often enough.

He listened as closely as he might to something he didn't really understand, for it was necessary to do so. He would expect William to listen to him.

How clearly he remembered it. He thought at the time he would not, but at the time, of course, he was not aware of what was happening. Thinking back, in the glare of hindsight, he found himself remembering whole sentences, virtually word for word.

"So it seemed to us," William said, "that the autistic child was not failing to receive the impressions, or even failing to interpret them in quite a sophisticated manner. He was, rather, disapproving them and rejecting them, without any loss of the potentiality of full communication if some impression could be found which he approved of."

"Ah," said Anthony, making just enough of a sound to indicate that he was listening.

"Nor can you persuade him out of his autism in any ordinary way, for he disapproves of you just as much as he disapproves of the rest of the world. But if you place him in conscious arrest-"

"In what?"

"It is a technique we have in which, in effect, the brain is divorced from the body and can perform its functions without reference to the body. It is a rather sophisticated technique devised in our own laboratory; actually-" He paused.

"By yourself?" asked Anthony gently. "Actually, yes," said William, reddening slightly, but clearly pleased. "In conscious arrest, we can supply the body with designed fantasies and observe the brain under differential electroencephalography. We can at once learn more about the autistic individual; what kind of sense impressions he most wants; and we learn more about the brain generally."

"Ah," said Anthony, and this time it was a real ah. "And all this you have learned about brains– can you not adapt it to the workings of a computer?"

"No," said William. "Not a chance. I told that to Dmitri. I know nothing about computers and not enough about brains."

"If I teach you about computers and tell you in detail what we need, what then?"

"It won't do. It-"

"Brother," Anthony said, and he tried to make it an impressive word. "You owe me something. Please make an honest attempt to give our problem some thought. Whatever you know about the brain-please adapt it to our computers."

William shifted uneasily, and said, "I understand your position. I will try. I will honestly try."