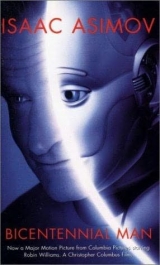

Текст книги "The Bicentennial Man and Other Stories"

Автор книги: Isaac Asimov

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Isaac Asimov

The Bicentennial Man and Other Stories

Dedicated to:

Judy-Lynn del Rey,

And the swath she is cutting in our field

Here I am with another collection of science fiction stories, and I sit here and think, with more than a little astonishment, that I have been writing and publishing science fiction now for just three-eighths of a century. This isn't bad for someone who only admits to being in his late youth-or a little over thirty, if pinned down.

It seems longer than that, I imagine, to most people who have tried to follow me from book to book and from field to field. As the flood of words continues year after year with no visible signs of letting up, the most peculiar misapprehensions naturally arise.

Just a few weeks ago, for instance, I was at a librarian's convention signing books, and some of the kindly remarks I received were:

"I can't believe you're still alive!"

"But how can you possibly look so young?"

"Are you really only one person?"

It goes even beyond that. In a review of one of my books [ASIMOV ON CHEMISTRY (Doubleday, 1974), and it was a very favorable review.] in the December 1975 Scientific American, I was described as: "Once a Boston biochemist, now label and linchpin of a New York corporate authorship-"

Dear me! Corporate authorship? Merely the linchpin and label?

It's not so. I'm sorry, if my copious output makes it seem impossible, but I'm alive, I'm young, and I'm only one person.

In fact, I'm an absolutely one-man operation. I have no assistants of any kind. I have no agent, no business manager, no research aides, no secretary, no stenographer. I do all my own typing, all my own proofreading, all my own indexing, all my own research, all my own letter writing, all my own telephone answering.

I like it that way. Since I don't have to deal with other people, I can concentrate more properly on my work, and get more done.

I was already worrying about this misapprehension concerning myself ten years ago. At that time, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (commonly known as F amp; SF) was planning a special Isaac Asimov issue for October 1966. I was asked for a new story to be included and I obliged [That story was THE KEY, and it appears in my collection ASIMOV'S MYSTERIES (Doubleday, 1968).], but I also wrote a short poem on my own initiative.

That poem appeared in the special issue and it has never appeared anywhere else-until now. I'm going to include it here because it's appropriate to my thesis. Then, too, seven years after the poem appeared, I recited it to a charming maiden, who, without any sign of mental effort, immediately suggested a change that was so inevitable, and so great an improvement, that I have to get the poem into print again in order to make that change.

I originally called the poem I'M IN THE PRIME OF LIFE, YOU ROTTEN KID! Edward L. Ferman, editor of F amp; SF, shortened that to THE PRIME OF LIFE. I like the longer version much better, but I decided it would look odd on the contents page, so I'm keeping the shorter version. (Heck!)

The Prime of Life

It was, in truth, an eager youth

Who halted me one day.

He gazed in bliss at me, and this

Is what he had to say;

"Why, mazel tov, it's Asimov,

A blessing on your head!

For many a year, I've lived in fear

That you were long since dead.

Or if alive, one fifty-five

Cold years had passed you by,

And left you weak, with poor physique,

Thin hair and rheumy eye.

For sure enough, I've read your stuff

Since I was but a lad

And couldn't spell or hardly tell

The good yarns from the bad.

My father, too, was reading you

Before he met my Ma.

For you he yearned, once he had learned

About you from his Pa.

Since time began, you wondrous man,

My ancestors did love

That s.f. dean and writing machine

The aged Asimov."

I'd had my fill. I said, "Be still!

I've kept my old-time spark.

My step is light, my eye is bright,

My hair is thick and dark."

His smile, in brief, spelled disbelief,

So this is what I did;

I scowled, you know, and with one blow,

I killed that rotten kid.

***

The change I mentioned occurs in the first line of the second stanza. I had it read, originally, "Why, stars above, it's Asimov," but the aforementioned maiden saw at once it ought to be "mazel tov." This is a Hebrew phrase meaning "good fortune" and it is used by Jews as a joyful greeting on jubilant occasions-as a meeting with me should surely be..

Ten years have passed since I wrote the poem and, of course, the impression of incredible age which I leave among those who know me only from my writings is now even stronger. When this poem was written, I had published a mere 66 books, and now, ten years later, the score stands at 175, so that it's been a decade of constant mental conflagration.

Just the same, I've kept my old-time spark even yet. My step is still light and my eye is still bright. What's more, I'm as suave in my conversations with young women as I have ever been (which is very suave indeed). That bit about my hair being "thick and dark" must be modified, however. There is no danger of baldness but, oh me, I am turning gray. In recent years, I have grown a generous pair of fluffy sideburns, and they are almost white.

And now that you know the worst about me, let's go on to the stories themselves or, rather (for you are not quite through with me), to my introductory comments to the first story.

The beginning of FEMININE INTUITION is tied up with Judy-Lynn Benjamin, whom I met at the World Science Fiction Convention in New York City in 1967. Judy-Lynn has to be seen to be believed-an incredibly intelligent, quick-witted, hard-driving woman who seems to be burning constantly with a bright radioactive glow.

She was managing editor of Galaxy in those days.

On March 21, 1971, she married that lovable old curmudgeon Lester del Rey, and knocked off all his rough edges in two seconds flat. At present, as Judy-Lynn del Rey, she is a senior editor at Ballantine Books and is generally recognized (especially by me) as one of the top editors in the business. [You may have noticed that this book is dedicated to her.]

Back in 1968, when Judy-Lynn was still at Galaxy, we were sitting in a bar in a New York hotel and she introduced me, I remember, to something called a "grasshopper." I told her I didn't drink because I had no capacity for alcohol, but she said I would like this one, and the trouble is I did.

It's a green cocktail with creme de menthe, and cream, and who knows what else in it, and it is delicious. I only had one on this occasion, so I merely graduated to a slightly higher than normal level of the loud bonhomie that usually characterizes me and was still sober enough to talk business. [A year or so later during the course of a science fiction convention, Judy-Lynn persuaded me to have two grasshoppers and I was instantly reduced to a kind of wild drunken merriment, and since then no one lets me have grasshoppers any more. Just as well!]

Judy-Lynn suggested I write a story about a female robot. Well, of course, my robots are sexually neutral, but they all have masculine names and I treat them all as males. The turnabout suggestion was good.

I said, "Gee, that's an interesting idea," and was awfully pleased, because Ed Ferman had asked me for a story with which to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of Fantasy and Science Fiction and I had agreed, but, at the moment, did not have an idea in my head.

On February 8, 1969, in line with the suggestion, I began FEMININE INTUITION. When it was done, Ed took it and the story was indeed included in the October 1969 Fantasy and Science Fiction, the twentieth-anniversary issue. It appeared as the lead novelette, too.

Between the time I sold it, however, and the time it appeared, Judy-Lynn said casually to me one day, "Did you ever do anything about my idea that you write a story about a female robot?"

I said enthusiastically, "Yes, I did, Judy-Lynn, and Ed Ferman is going to publish it. Thanks for the suggestion."

Judy-Lynn's eyes opened wide and she said in a very dangerous voice, "Stories based on my ideas go to me, you dummy. You don't sell them to the competition."

She went on to expound on that theme for about half an hour and my attempts to explain that Ed had asked me for a story before the time of the suggestion and that she had never quite made it clear that she wanted the story for herself were brushed aside with scorn.

Anyway, Judy-Lynn, here's the story again, and I'm freely admitting that the suggestion of a female robot was yours. Does that make everything all right? (No, I didn't think so.)

Feminine Intuition

The Three Laws of Robotics:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

For the first time in the history of United States Robots and Mechanical Men Corporation, a robot had been destroyed through accident on Earth itself.

No one was to blame. The air vehicle had been demolished in mid-air and an unbelieving investigating committee was wondering whether they really dared announce the evidence that it had been hit by a meteorite. Nothing else could have been fast enough to prevent automatic avoidance; nothing else could have done the damage short of a nuclear blast and that was out of the question.

Tie that in with a report of a flash in the night sky just before the vehicle had exploded-and from Flagstaff Observatory, not from an amateur-and the location of a sizable and distinctly meteoric bit of iron freshly gouged into the ground a mile from the site and what other conclusion could be arrived at?

Still, nothing like that had ever happened before and calculations of the odds against it yielded monstrous figures. Yet even colossal improbabilities can happen sometimes.

At the offices of United States Robots, the hows and whys of it were secondary. The real point was that a robot had been destroyed.

That, in itself, was distressing.

The fact that JN-5 had been a prototype, the first, after four earlier attempts, to have been placed in the field, was even more distressing.

The fact that JN-5 was a radically new type of robot, quite different from anything ever built before, was abysmally distressing.

The fact that JN-5 had apparently accomplished something before its destruction that was incalculably important and that that accomplishment might now be forever gone, placed the distress utterly beyond words.

It seemed scarcely worth mentioning that, along with the robot, the Chief Robopsychologist of United States Robots had also died.

Clinton Madarian had joined the firm ten years before. For five of those years, he had worked uncomplainingly under the grumpy supervision of Susan Calvin.

Madarian's brilliance was quite obvious and Susan Calvin had quietly promoted him over the heads of older men. She wouldn't, in any case, have deigned to give her reasons for this to Research Director Peter Bogert, but as it happened, no reasons were needed. Or, rather, they were obvious.

Madarian was utterly the reverse of the renowned Dr. Calvin in several very noticeable ways. He was not quite as overweight as his distinct double chin made him appear to be, but even so he was overpowering in his presence, where Susan had gone nearly unnoticed. Madarian's massive face, his shock of glistening red-brown hair, his ruddy complexion and booming voice, his loud laugh, and most of all, his irrepressible self-confidence and his eager way of announcing his successes, made everyone else in the room feel there was a shortage of space.

When Susan Calvin finally retired (refusing, in advance, any cooperation with respect to any testimonial dinner that might be planned in her honor, with so firm a manner that no announcement of the retirement was even made to the news services) Madarian took her place.

He had been in his new post exactly one day when he initiated the JN project.

It had meant the largest commitment of funds to one project that United States Robots had ever had to weigh, but that was something which Madarian dismissed with a genial wave of the hand.

"Worth every penny of it, Peter," he said. "And I expect you to convince the Board of Directors of that."

"Give me reasons," said Bogert, wondering if Madarian would. Susan Calvin had never given reasons.

But Madarian said, "Sure," and settled himself easily into the large armchair in the Director's office.

Bogert watched the other with something that was almost awe. His own once-black hair was almost white now and within the decade he would follow Susan into retirement. That would mean the end of the original team that had built United States Robots into a globe-girdling firm that was a rival of the national governments in complexity and importance. Somehow neither he nor those who had gone before him ever quite grasped the enormous expansion of the firm.

But this was a new generation. The new men were at ease with the Colossus" They lacked the touch of wonder that would have them tiptoeing in disbelief. So they moved ahead, and that was good.

Madarian said, "I propose to begin the construction of robots without constraint."

"Without the Three Laws? Surely-"

"No, Peter. Are those the only constraints you can think of? Hell, you contributed to the design of the early positronic brains. Do I have to tell you that, quite aside from the Three Laws, there isn't a pathway in those brains that isn't carefully designed and fixed? We have robots planned for specific tasks, implanted with specific abilities."

"And you propose-"

"That at every level below the Three Laws, the paths be made open-ended. It's not difficult."

Bogert said dryly, "It's not difficult, indeed. Useless things are never difficult. The difficult thing is fixing the paths and making the robot useful."

"But why is that difficult? Fixing the paths requires a great deal of effort because the Principle of Uncertainty is important in particles the mass of positrons and the uncertainty effect must be minimized. Yet why must it? If we arrange to have the Principle just sufficiently prominent to allow the crossing of paths unpredictably-"

"We have an unpredictable robot."

"We have a creative robot," said Madarian, with a trace of impatience. "Peter, if there's anything a human brain has that a robotic brain has never had, it's the trace of unpredictability that comes from the effects of uncertainty at the subatomic level. I admit that this effect has never been demonstrated experimentally within the nervous system, but without that the human brain is not superior to the robotic brain in principle."

"And you think that if you introduce the effect into the robotic brain, the human brain will become not superior to the robotic brain in principle."

"That, " said Madarian, "is exactly what I believe." They went on for a long time after that.

The Board of Directors clearly had no intention of being easily convinced.

Scott Robertson, the largest shareholder in the firm, said, "It's hard enough to manage the robot industry as it is, with public hostility to robots forever on the verge of breaking out into the open. If the public gets the idea that robots will be uncontrolled…Oh, don't tell me about the Three Laws. The average man won't believe the Three Laws will protect him if he as much as hears the word 'uncontrolled.' "

"Then don't use it, " said Madarian. "Call the robot-call it 'intuitive.' "

"An intuitive robot, " someone muttered. "A girl robot?" A smile made its way about the conference table.

Madarian seized on that. "All right. A girl robot. Our robots are sexless, of course, and so will this one be, but we always act as though they're males. We give them male pet names and call them he and him. Now this one, if we consider the nature of the mathematical structuring of the brain which I have proposed, would fall into the JN-coordinate system. The first robot would be JN-1, and I've assumed that it would be called John-10…I'm afraid that is the level of originality of the average roboticist. But why not call it Jane-1, damn it? If the public has to be let in on what we're doing, we're constructing a feminine robot with intuition."

Robertson shook his head, "What difference would that make? What you're saying is that you plan to remove the last barrier which, in principle, keeps the robotic brain inferior to the human brain. What do you suppose the public reaction will be to that?"

"Do you plan to make that public?" said Madarian. He thought a bit and then said, "Look. One thing the general public believes is that women are not as intelligent as men."

There was an instant apprehensive look on the face of more than one man at the table and a quick look up and down as though Susan Calvin were still in her accustomed seat.

Madarian said, "If we announce a female robot, it doesn't matter what she is. The public will automatically assume she is mentally backward. We just publicize the robot as Jane-1 and we don't have to say another word. We're safe."

"Actually," said Peter Bogert quietly, "there's more to it than that. Madarian and I have gone over the mathematics carefully and the JN series, whether John or Jane, would be quite safe. They would be less complex and intellectually capable, in an orthodox sense, than many another series we have designed and constructed. There would only be the one added factor of, well, let's get into the habit of calling it 'intuition.' "

"Who knows what it would do?" muttered Robertson.

"Madarian has suggested one thing it can do. As you all know, the Space Jump has been developed in principle. It is possible for men to attain what is, in effect, hyper-speeds beyond that of light and to visit other stellar systems and return in negligible time-weeks at the most."

Robertson said, "That's not new to us. It couldn't have been done without robots."

"Exactly, and it's not doing us any good because we can't use the hyper-speed drive except perhaps once as a demonstration, so that U. S. Robots gets little credit. The Space Jump is risky, it's fearfully prodigal of energy and therefore it's enormously expensive. If we were going to use it anyway, it would be nice if we could report the existence of a habitable planet. Call it a psychological need. Spend about twenty billion dollars on a single Space Jump and report nothing but scientific data and the public wants to know why their money was wasted. Report the existence of a habitable planet, and you're an interstellar Columbus and no one will worry about the money."

"So?"

"So where are we going to find a habitable planet? Or put it this way-which star within reach of the Space Jump as presently developed, which of the three hundred thousand stars and star systems within three hundred light-years has the best chance of having a habitable planet? We've got an enormous quantity of details on every star in our three-hundred-light-year neighborhood and a notion that almost every one has a planetary system. But which has a habitable planet? Which do we visit?…We don't know."

One of the directors said, "How would this Jane robot help us?"

Madarian was about to answer that, but he gestured slightly to Bogert and Bogert understood. The Director would carry more weight. Bogert didn't particularly like the idea; if the JN series proved a fiasco, he was making himself prominent enough in connection with it to insure that the sticky fingers of blame would cling to him. On the other hand, retirement was not all that far off, and if it worked, he would go out in a blaze of glory. Maybe it was only Madarian's aura of confidence, but Bogert had honestly come to believe it would work.

He said, "It may well be that somewhere in the libraries of data we have on those stars, there are methods for estimating the probabilities of the presence of Earth-type habitable planets. All we need to do is understand the data properly, look at them in the appropriate creative manner, make the correct correlations. We haven't done it yet. Or if some astronomer has, he hasn't been smart enough to realize what he has.

"A JN-type robot could make correlations far more rapidly and far more precisely than a man could. In a day, it would make and discard as many correlations as a man could in ten years. Furthermore, it would work in truly random fashion, whereas a man would have a strong bias based on preconception and on what is already believed."

There was a considerable silence after that Finally Robertson said, "But it's only a matter of probability, isn't it? Suppose this robot said, 'The highest-probability habitable-planet star within so-and-so light-years is Squidgee-17" or whatever, and we go there and find that a probability is only a probability and that there are no habitable planets after all. Where does that leave us?"

Madarian struck in this time. "We still win. We know how the robot came to the conclusion because it-she-will tell us. It might well help us gain enormous insight into astronomical detail and make the whole thing worthwhile even if we don't make the Space Jump at all. Besides, we can then work out the five most probable sites of planets and the probability that one of the five has a habitable planet may then be better than 0.95. It would be almost sure-"

They went on for a long time after that.

The funds granted were quite insufficient, but Madarian counted on the habit of throwing good money after bad. With two hundred million about to be lost irrevocably when another hundred million could save everything, the other hundred million would surely be voted.

Jane-1 was finally built and put on display. Peter Bogert studied it -her-gravely. He said, "Why the narrow waist? Surely that introduces a mechanical weakness?"

Madarian chuckled. "Listen, if we're going to call her Jane, there's no point in making her look like Tarzan."

Bogert shook his head. "Don't like it. You'll be bulging her higher up to give the appearance of breasts next, and that's a rotten idea. If women start getting the notion that robots may look like women, I can tell you exactly the kind of perverse notions they'll get, and you'll really have hostility on their part."

Madarian said, "Maybe you're right at that. No woman wants to feel replaceable by something with none of her faults. Okay."

Jane-2 did not have the pinched waist. She was a somber robot which rarely moved and even more rarely spoke.

Madarian had only occasionally come rushing to Bogert with items of news during her construction and that had been a sure sign that things were going poorly. Madarian's ebullience under success was overpowering. He would not hesitate to invade Bogert's bedroom at 3 A.M. with a hot-flash item rather than wait for the morning. Bogert was sure of that.

Now Madarian seemed subdued, his usually florid expression nearly pale, his round cheeks somehow pinched. Bogert said, with a feeling of certainty, "She won't talk."

"Oh, she talks." Madarian sat down heavily and chewed at his lower lip. "Sometimes, anyway," he said.

Bogert rose and circled the robot. "And when she talks, she makes no sense, I suppose. Well, if she doesn't talk, she's no female, is she?"

Madarian tried a weak smile for size and abandoned it. He said, "The brain, in isolation, checked out."

"I know," said Bogert. "But once that brain was put in charge of the physical apparatus of the robot, it was necessarily modified, of course."

"Of course," agreed Bogert unhelpfully. "But unpredictably and frustratingly. The trouble is that when you're dealing with n-dimensional calculus of uncertainty, things are-"

"Uncertain?" said Bogert. His own reaction was surprising him. The company investment was already most sizable and almost two years had elapsed, yet the results were, to put it politely, disappointing. Still, he found himself jabbing at Madarian and finding himself amused in the process.

Almost furtively, Bogert wondered if it weren't the absent Susan Calvin he was jabbing at. Madarian was so much more ebullient and effusive than Susan could ever possibly be-when things were going well. He was also far more vulnerably in the dumps when things weren't going well, and it was precisely under pressure that Susan never cracked. The target that Madarian made could be a neatly punctured bull's-eye as recompense for the target Susan had never allowed herself to be.

Madarian did not react to Bogert's last remark any more than Susan Calvin would have done; not out of contempt, which would have been Susan's reaction, but because he did not hear it

He said argumentatively, "The trouble is the matter of recognition. We have Jane-2 correlating magnificently. She can correlate on any subject, but once she's done so, she can't recognize a valuable result from a valueless one. It's not an easy problem, judging how to program a robot to tell a significant correlation when you don't know what correlations she will be making."

"I presume you've thought of lowering the potential at the W-21 diode junction and sparking across the-"

"No, no, no, no-" Madarian faded off into a whispering diminuendo. "You can't just have it spew out everything. We can do that for ourselves. The point is to have it recognize the crucial correlation and draw the conclusion. Once that is done, you see, a Jane robot would snap out an answer by intuition. It would be something we couldn't get ourselves except by the oddest kind of luck."

"It seems to me," said Bogert dryly, "that if you had a robot like that, you would have her do routinely what, among human beings, only the occasional genius is capable of doing."

Madarian nodded vigorously. "Exactly, Peter. I'd have said so myself if I weren't afraid of frightening off the execs. Please don't repeat that in their hearing."

"Do you really want a robot genius?"

"What are words? I'm trying to get a robot with the capacity to make random correlations at enormous speeds, together with a key-significance high-recognition quotient. And I'm trying to put those words into positronic field equations. I thought I had it, too, but I don't. Not yet."

He looked at Jane-2 discontentedly and said, "What's the best significance you have, Jane?"

Jane-2's head turned to look at Madarian but she made no sound, and Madarian whispered with resignation, "She's running that into the correlation banks."

Jane-2 spoke tonelessly at last. "I'm not sure." It was the first sound she had made.

Madarian's eyes rolled upward. "She's doing the equivalent of setting up equations with indeterminate solutions."

"I gathered that," said Bogert. "Listen, Madarian, can you go anywhere at this point, or do we pull out now and cut our losses at half a billion?"

"Oh, I'll get it, " muttered Madarian.

Jane-3 wasn't it. She was never as much as activated and Madarian was in a rage.

It was human error. His own fault, if one wanted to be entirely accurate. Yet though Madarian was utterly humiliated, others remained quiet. Let he who has never made an error in the fearsomely intricate mathematics of the positronic brain fill out the first memo of correction.

Nearly a year passed before Jane-4 was ready. Madarian was ebullient again. "She does it," he said. "She's got a good high-recognition quotient."

He was confident enough to place her on display before the Board and have her solve problems. Not mathematical problems; any robot could do that; but problems where the terms were deliberately misleading without being actually inaccurate.

Bogert said afterward, "That doesn't take much, really."

"Of course not. It's elementary for Jane-4 but I had to show them something, didn't I?"

"Do you know how much we've spent so far?"

"Come on, Peter, don't give me that. Do you know how much we've got back? These things don't go on in a vacuum, you know. I've had over three years of hell over this, if you want to know, but I've worked out new techniques of calculation that will save us a minimum of fifty thousand dollars on every new type of positronic brain we design, from now on in forever. Right?"

"Well-"

"Well me no wells. It's so. And it's my personal feeling that n-dimensional calculus of uncertainty can have any number of other applications if we have the ingenuity to find them, and my Jane robots will find them. Once I've got exactly what I want, the new JN series will pay for itself inside of five years, even if we triple what we've invested so far."

"What do you mean by 'exactly what you want'? What's wrong with Jane-4?"

"Nothing. Or nothing much. She's on the track, but she can be improved and I intend to do so. I thought I knew where I was going when I designed her. Now I've tested her and I know where I'm going. I intend to get there."

Jane-5 was it. It took Madarian well over a year to produce her and there he had no reservations; he was utterly confident.

Jane-5 was shorter than the average robot, slimmer. Without being a female caricature as Jane-1 had been, she managed to possess an air of femininity about herself despite the absence of a single clearly feminine feature.

"It's the way she's standing," said Bogert. Her arms were held gracefully and somehow the torso managed to give the impression of curving slightly when she turned.

Madarian said, "Listen to her…How do you feel, Jane?"

"In excellent health, thank you," said Jane-5, and the voice was precisely that of a woman; it was a sweet and almost disturbing contralto.

"Why did you do that, Clinton?" said Peter, startled and beginning to frown.

"Psychologically important," said Madarian. "I want people to think of her as a woman; to treat her as a woman; to explain."

"What people?" Madarian put his hands in his pockets and stared thoughtfully at Bogert. "I would like to have arrangements made for Jane and myself to go to flagstaff."

Bogert couldn't help but note that Madarian didn't say Jane-5. He made use of no number this time. She was the Jane. He said doubtfully, "To flagstaff? Why?"