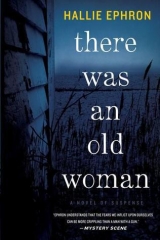

Текст книги "There was an old woman"

Автор книги: Hallie Ephron

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-nine

Mina turned down Evie’s offer to stay and help clean up. It was the last thing the poor girl needed after the day that she’d been through. Besides, Mina was far too embarrassed by what had happened.

With all the windows and doors open, the smoke began to clear, though the odors of burned chicken and tomato were still pungent in the air. She scraped what she could into the garbage. Filled the pot with hot water and a few squirts of dishwashing liquid. Maybe it was salvageable. She stood there, staring into suds that rapidly turned black. Maybe not.

How could this have happened? She always, always, always set the burner to low when she made chicken cacciatore. But when she’d fought her way through the smoky kitchen to turn off the burner, she found the dial cranked well past medium.

On top of that, despite thick smoke, the alarm hadn’t sounded. Hadn’t it gone off yesterday when her teapot went up? Wasn’t it supposed to reset itself automatically? Mina took out a broom and jammed the end of the stick up into the smoke alarm’s test button, expecting to hear the shrill alarm sound. But nothing happened.

Maybe the battery had run down, though that made no sense either. It was supposed to at least chirp for a while before it died. She was sure she had a replacement battery, and she knew exactly where it was in the storage closet in the bag where she kept lightbulbs. But even standing on her kitchen step stool she wasn’t nearly tall enough, never mind steady enough, to reattach the wires and replace the battery. Tomorrow, she’d get someone—Brian or Finn—to give her a hand.

She wrote a reminder on a Post-it and stuck it to her refrigerator door. Then, wearily she took down her calendar and continued the list she’d started, writing more items in today’s block:

5. Burned chicken

6. Smoke alarm dead

She hung her calendar back on its hook. Maybe it was just as well that she’d broken down and agreed to visit nursing homes with Brian. She hated the idea that she’d end up in one of those places, but at least there she wouldn’t be burning down the neighborhood.

Back when Annabelle was still lucid most of the time, Mina had taken her to visit several nursing homes that took care of people with dementia. Annabelle had chosen Pelham Manor. True, it was a bit shabby, but it was clean and well run, and she’d wanted to be nearby, so Mina could get there easily. Annabelle had been fortunate to have had particularly kind caregivers.

Mina remembered the day she’d moved Annabelle into a freshly painted room. She’d loaded her sister’s few meager suitcases and some boxed-up framed photographs and personal items into the trunk of her car. Even though it had been swelteringly hot that day, Annabelle insisted on riding with the car windows rolled up. She had sat bolt upright in the passenger seat, her eyes bright as buttons, to use one of their mother’s expressions, as their old neighborhood streamed by.

“Are you sure there’s enough gas?” Annabelle had asked. She asked the same thing every time she got in the car with Mina—or in a cab, or even on a bus, for that matter.

“We’re going to run out of gas,” Annabelle said for the third time as they passed a gas station. A half block later, “Shouldn’t we get gas?”

“Look,” Mina said, pointing to the needle that showed well over half a tank. “There’s plenty. Relax.”

But relax was one of the many things that Annabelle could no longer do. Sitting there in her coat, sweat streaming down her face, she’d clutched the armrest and twisted in her seat, watching the blue-and-yellow Sunoco sign recede behind them, so agitated that the knuckles on the hand Mina could see turned white. With the other hand, she pulled at her hair, yanking out pins that Mina had so carefully put in not twenty minutes earlier.

Irrational anxiety—the doctor had already warned Mina about that and told her that it was likely to increase as dementia deepened. Mina had learned from experience that it was immune to reasoning or hard evidence. Distraction was the only strategy that seemed to work, even temporarily.

So, when they came to a stop at a red light, Mina pointed to the opposite corner. “Oh Annabelle, look. What happened to the movie theater that used to be over there on that corner?”

It took Annabelle a few seconds to refocus—as if gears were shifting and cogs falling into place. But when she did, her expression softened, and the lines of tension eased from around her eyes. “Oh yes, the Halcyon.”

Mina had forgotten that the movie theater, with its gilded ceiling and massive crystal chandelier, had been called the Halcyon—from halcyon days, how appropriate. The light turned green, and Mina accelerated.

“Popcorn,” Annabelle said. “Can I get a large?”

At least Annabelle had died first, as Mina had hoped and prayed she would, with Mina sitting by her side and holding her hand. Would anyone be there with Mina to hold her hand at the end?

Chapter Thirty

Getting old sucked, Evie thought as she crossed back to her mother’s house. She left behind wet footprints in the tall grass, already flattened by the heavy rain. Would she go out flailing and dwindling like her mother or fighting—she noticed the open garage with the light on—and sweeping up cat litter like Mrs. Yetner?

She detoured to the garage. The pile of litter was mounded on the floor near the back, and the smell of gas had completely vanished. She’d deal with it tomorrow. She turned off the light, pulled down the door, and returned to the house. The minute she’d unlocked the front door and pushed it open, an overpowering smell, both acrid and sweet, sent her reeling back. Roach bombs. She’d forgotten all about them.

She took a deep breath before plunging in and racing from window to window, throwing them open. When she got to the back door, she pulled it open, stepped outside onto the back porch, and gasped for breath. The light mist and stiff breeze that whipped off the marsh felt good on her face. She stayed out there for a few minutes, giving the house and her own lungs time to air out before going back inside.

In the bedroom she found a sweatshirt and sweatpants in her mother’s bureau and a pair of warm socks. She shucked her damp clothes and changed. Returning to the living room, she stood there, looking around. Something felt off, but she couldn’t put her finger on what.

The photos were still in their places on the mantel. The pattern of dust on the coffee table showed where Evie had cleared away ashtrays and papers. The TV was still on the wall. Still, she couldn’t shake a feeling of unease.

Her neck prickled as she realized what it was. The TV’s shipping box with the SONY logo was no longer leaning against the side of the sofa. It was gone. What else?

Evie walked through the dining room and into the kitchen. Slowly she did a 360. Cabinets and drawers were open. She’d left them that way. The bills and statements were still in orderly rows on the kitchen table. Or . . . not quite. The rows looked as if they’d been slightly disturbed. She could easily have done that herself when she went crashing through to open the windows.

But when she looked more carefully at the piles, she realized it was more than that. The phone bill on the top of one of them was six months old. When she’d finished sorting, the newest one would have been on top.

Someone had been in the house, and it only now occurred to her that it was just possible that the person was still there. Evie grabbed her purse, ran out of the house, and dialed 911.

Evie waited outside in a light drizzle for the police, wondering if the officer who’d rousted Mrs. Yetner off Mr. Cutler’s porch would show up. But the two officers who climbed out of the cruiser that arrived after a ten-minute wait were strangers. One, barrel chested and straight backed, was not much older than Evie. She followed his gaze as he took in the house, reminded again of how appalling it looked: graffiti, sodden bags of trash, and a soiled mattress leaning up against the side, and landscaping that belonged in a vacant lot.

The other officer, an older man, tall with a stiff gait, went into her mother’s house while the younger one came over to talk to her. Evie felt silly telling him about the missing packing box and that papers had been rearranged. But he didn’t seem to think it was silly at all. He wrote down everything she said.

The older officer emerged from her mother’s house and strode over to them. “It’s okay. No one’s inside. There’s no sign of a forced entry. You sure you left the house locked?”

“Absolutely.”

“When did you leave?”

“At around eleven this morning.”

“Anyone else have keys to the house?” he asked.

“My sister. She’s in Connecticut. And”—Evie swallowed a twinge of guilt—“the man who runs the convenience store up the street has keys to the garage. Maybe to the house, too. I don’t know. He was over here this morning, helping me with my mother’s car.”

“You were right to get out of there and call us,” the older officer said. “I’m going to talk with your neighbors. See if anyone saw anything.”

He strode next door where Mrs. Yetner was peering out from behind her screen door.

The younger officer said, “So a cardboard box is missing?”

“I didn’t really have time to check. There might be more.”

“Why don’t we go in and you have a look around?”

Evie agreed, glad not to be going back inside by herself. The officer hung back, following her from room to room. In her mother’s bedroom, she checked her jewelry drawer. There, amid a jumble of rhinestones and fake pearls, were her grandmother’s diamond wedding ring and the sapphire earrings that her dad had given her mother on their twentieth anniversary. In the dining room, her mother’s few pieces of good silver were still there. Beyond that, there wasn’t much of value to take. Not any longer.

“Up until this morning,” Evie told the police officer, “there was a fair amount of cash in the house.”

That got his attention. “Really?”

“Thousands of dollars. I’d taken it with me.”

“Lucky thing you did. Who knew your mother was keeping cash in the house?”

“Obviously whoever gave it to her. But I have no idea who that was, and she’s not telling.”

“She didn’t have any friends?”

“There’s the man across the street. He came over to ask me if he could do anything to help. I got the impression that he and my mother were good friends.”

“What about the man with the keys to her garage? Was he a good friend, too?” he asked, raising his eyebrows.

Evie felt herself flush. “Not that kind of friend.”

When they got back outside, Evie glanced across the street to where the second officer was ringing Frank Cutler’s bell. That house was dark, and the garage was open and empty. The officer gave up and tried the house next door.

“Okay, then. I guess that about wraps it up,” the younger officer said, handing her his card. He put away his notebook and looked as if he was anxious to be off. “Call if you discover anything else missing. And if I were you, I’d get the locks changed immediately.”

The older officer came back. “Just the old woman living next door is around. She has an interesting theory. She says the man who lives over there”—he indicated across the street toward Mr. Cutler’s house—“was out in front of your house earlier today. Talking to a tow truck driver who picked up a car. She thinks she saw a box in the driveway. Says she’s sure the man took it with him. But you can take that with a grain of salt. She calls us all the time, almost always with some complaint about that neighbor.”

Evie looked next door. Mrs. Yetner was still standing in her doorway, the screen pushed open. Was she a reliable witness or did she see what she wanted to see?

“Besides,” the officer added, “I’m not sure her eyesight is all that good.”

Evie waved at Mrs. Yetner. Her neighbor certainly saw her well enough to wave back.

Chapter Thirty-one

Mina had been surprised to see the police officers next door talking to Evie. Even more surprised when one of them came over to talk to her. As often as she called the police, she couldn’t remember the last time they’d actually stopped and questioned her. She was lucky if they slowed down when they rolled by.

Now she watched as the pair got back into their cruiser and drove off. Sandra Ferrante’s daughter was still out on her mother’s front steps, standing there like the poor thing didn’t have the good sense to come in out of the rain.

Mina pulled an umbrella from the stand and walked next door, picking her way across the wet lawn. “You had a break-in?”

“That’s what it looks like. Did you see anyone trying to get into the house?”

“I didn’t. But I was busy.” She’d gotten the chicken started, sat down to read, and then fallen asleep. The rain had woken her. When it let up, she’d taken the kitty litter over and sprinkled it over the gasoline spill. Young people had no idea how easy it was for a fire to get started. “What did they take?”

“Nothing, really.”

“What kind of nothing?”

The girl squirmed under Mina’s gaze. “A brown shipping box. Who’d bother with that?”

The girl must have been talking about the box that Mina had seen sitting at the end of the driveway getting rained on. Or maybe it had been in the grass. Weeds, really. Mina doubted if there was even a single sprout of actual bluegrass or fescue left in that yard. Then she’d gotten distracted by the sound of the winch raising the car and the spectacle of the truck driving off with the car in tow. After that, Frank had disappeared and she couldn’t recall seeing the box again.

“A big box?” Mina stretched her arms wide. “And flat?”

“Where did you see it?”

“Out in front of your house when he”—she tipped her head in the direction of the house across the street—“was out there chatting up the tow truck driver. I don’t know what he’s up to but he’s a schemer, that one.” Mina felt her face grow warm. “And he’s been hanging around your mother.” Like smell on a dead fish, as her father liked to say. “Helping out.” Mina sniffed.

As if that man were capable of helping anyone other than himself. Oh, he’d been pleasant enough when he first moved in. Brought her a bottle of sweet sherry that she’d never even opened. Even her grandmother hadn’t had a taste for sherry. Offered to clear the leaves off her lawn when she’d complained about the infernal noise of his leaf blower.

“He thinks I haven’t heard him, going through my trash in the middle of the night.” Mina caught the girl’s skeptical look. “More than once.”

“I know you don’t like him very much.” The girl had her arms folded in front of her as she pinched and tweaked her sleeves. “Are you sure you saw him actually walk off with that box?”

“Well.” Mina dropped her gaze. “Maybe not walk off with it.”

“Mrs. Yetner, whoever got in didn’t break in. I know Finn has a key to the garage. But maybe you know if my mother gave house keys to anyone else.”

Mina fastened the top button of her blouse and pulled her sweater around her. The question flustered her, because somewhere, deep in the recesses of her memory, she did recall that Sandra Ferrante had, once upon a time, given her a key to her front door. It was years and years ago, when the girls were little and sometimes locked themselves out. Mina had a vague memory of slipping the key into an envelope and writing Ferrante on it. But where it had gotten to, she had no idea.

“You don’t think I—” Mina started. “Because I would never—”

“You? Of course not,” the girl said, her cheeks blazing. “It’s just that whoever got in must have a key. Which means they can get in whenever they want to. And I might not even have noticed except the papers were—” Her voice cracked and she took a breath. “And I don’t know if it’s random or what.” The poor girl was trembling.

“Shhhh,” Mina said, putting her arm around her. “The thing to do is get the locks changed. Right away. And why don’t you stay overnight with us? Ivory will be delighted.” She could read Evie’s guarded look. “I promise not to leave a pot on the stove and burn the house down.”

Chapter Thirty-two

It had been so sweet of Mrs. Yetner to invite Evie to stay over, and though Evie had no intention of taking her up on it, knowing that she had the option made her feel safer and less alone. It was chilly and damp when she got back inside. The insecticide smell hadn’t vanished completely, and in the kitchen a single pantry moth fluttered drunkenly about. With her bare hand, she smacked it against the wall.

It took four calls to locksmiths listed in her mother’s 2008 copy of the Yellow Pages before she found one that was still in business and taking calls on a Sunday night. In return for payment in cash, the woman who took her call promised someone would be there in an hour.

Evie hung up and called Ginger. “The house got broken into,” Evie said as soon as Ginger picked up, “but they didn’t take anything valuable.”

“Oh my God. What next? Are you okay?” Ginger asked, her voice rising. “Did you call the police?”

“I’m fine. Of course I did.”

“Did they make a mess?”

“No. In fact, if I wasn’t so anal about the way I sorted Mom’s papers, I never would have realized the house was broken into. And before you ask, I’ve got someone coming to change the locks.”

“Tonight?”

“In an hour.”

“You sure you’re okay?”

“Other than a headache—” Evie put her hand to her temple and massaged the spot that had started to throb. Headaches that started that way usually turned into doozies. She started for the bathroom where she’d seen some Excedrin in the medicine cabinet. “—I’m fine.”

“It’s a good thing you had all that money with you,” Ginger said.

“Good thing,” Evie said as she ran water in the bathroom sink and splashed her face with one hand. “I’ll deposit it first thing tomorrow.”

“You’re sure nothing else is missing?”

“Ginger, I checked everywhere.” Evie opened the medicine cabinet. “I’m sure—”

But the words died on her lips, and the phone dropped into the sink with a clatter. Except for the tube of Crest toothpaste that she was sure she’d left on the sink, the bottom shelf of the medicine cabinet was empty.

She picked up the phone. “You’re not going to believe this. Everything that was on one shelf of Mom’s medicine cabinet is missing.”

“That’s weird. Were there any prescription drugs?”

“I don’t remember anything like that.” Evie conjured a visual image of what else she’d seen. “She had Excedrin. Vitamins. Maybe some cold medicine. I can’t remember what else.”

“Excedrin and vitamins?” After a long silence, Ginger added, “You know, I’d find it more reassuring if whoever broke in had taken her jewelry and her goddamned TV. Because this is just plain creepy. I don’t think you should stay there.”

“I can’t leave now. I’ve got a locksmith on his way over. At least when he’s done, I’ll be the only one with a key.”

“Then I’m coming to stay with you.”

“You are not.” The doorbell rang. “That’s the locksmith. Don’t worry. Mrs. Yetner invited me to stay with her, and I will if I need to.”

“How do you know she wasn’t the one who broke in?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Evie said and disconnected the call.

Chapter Thirty-three

Brian arrived the next morning, hours earlier than Mina expected him. She was still eating her breakfast and reading the paper.

“You remembered I was coming, didn’t you?” he said. “You’re up to looking at residences?”

Of course she did. Of course she was. She took a drink of tea, scraped up a last mouthful of oatmeal, and walked the dishes to the sink.

“I’ve arranged for us to see a few places.” He read from a piece of paper. “Pelham Manor. Golden Oaks—”

She took the paper from him and adjusted her glasses. “I can read, for heaven’s sake.”

He had four addresses written down. Pelham Manor was where Annabelle had spent her final days. Golden Oaks was also in the Bronx. Briarfield Gardens was on Saw Mill River Road, over into Westchester. The fourth place she’d never heard of. Visiting four in a single day seemed awfully ambitious.

She handed him back the paper. “Have you eaten? Can I get you anything?”

“I’m fine.” He looked at his watch. “We’ve got to step on it, Aunt Mina. They’re expecting us at Pelham Manor in thirty minutes.”

Mina folded the newspaper, slapped it down on the table, and stood. “All right then. I’ll be ready in a minute.”

She closed herself in the bathroom, even though she didn’t need to go. Then she sat on the closed toilet seat trying to calm herself. She’d thought she’d be fine, visiting old age homes. But she wasn’t. She did not want to leave her house. Her neighborhood. Her marsh. Besides, she was nowhere near that far gone. Or am I? she wondered as she stared down at the backs of her hands, the veins popping beneath skin that was shriveled like loose latex.

“Aunt Mina, you haven’t forgotten I’m out here waiting for you, have you?”

“Not yet.” Mina reached back and flushed the toilet.

“Do you need any help?”

“Don’t be ridiculous.” She stood and checked her face in the mirror, relaxing the frown lines as much as she still could and smoothing her chins. She splashed her face with warm water and dried it.

From the other side of the door, Brian called, his voice sounding more urgent, “I’ll go start the car and meet you—”

She banged out of the bathroom. “Don’t bother. I’ll drive.” She found her purse sitting on the placemat in the kitchen, snagged her cane, and stumped out the door. Immediately she realized it had started to rain again. She should have picked up an umbrella, but she’d be damned if she was going to go back for it now.

She waited until Brian got in the car and had shut the door, too, before releasing the brake and slamming the car into drive. Let him sulk. He’d been doing that since he was three years old, whenever things didn’t go precisely his way. Once on the street she accelerated, holding on to the wheel to pull herself up a little taller to see over the steering wheel. Had she shrunk more? With relief, she noticed a cushion from the seat was on the floor. The girl must have left it there.

When they’d emerged from her little pocket of residential streets, Brian said, “So you know where you’re going?”

She harrumphed. Did he think she could forget how to drive to a place she’d gone every day for two years? When Brian put in an occasional appearance there, he’d acted as if he deserved a medal.

She bypassed the highway on-ramp, and he asked again if she knew how to get there.

“This is the way I go.” She wanted to say, Shall I let you off and you can take the bus? She chuckled to herself, imagining him standing on the street corner and receding in her rearview mirror.

Mina didn’t take highways. Not anymore. Whenever she tried to, it seemed as if they’d repainted the lines to make the lanes even narrower, while those big rigs that rumbled along at top speed and tailgated her had grown longer and wider.

She didn’t drive at night, either. Ever. It wasn’t so much that she couldn’t see, though that was a piece of it. She could swear that some oncoming headlights on new cars were brighter than brights. Apparently those new blue headlights were legal, though she couldn’t imagine why, because they were blinding. Those seconds it took for her eyes to recover from them were terrifying. Plenty of time to run someone over or give herself a heart attack.

No, she’d stick to daytime driving, thank you very much. As Mina drove up the street, the phantom smell of yeast teased her nose. A Wonder Bread factory had once been nearby.

“You’d better lock your door,” she told Brian as they passed a row of derelict houses. Those had been brand-new when she was in elementary school, but now their perimeters were surrounded by battered chain-link fencing. A stout dog, tied to a front porch railing, barked as they drove by.

It was a little farther to Pelham Bay Park, where her mother used to take Mina and Annabelle to play when they were little. There, in the distance, were the Co-op City towers, standing on the banks of the Hutchinson River on land that had been a broad flat expanse her father used to call “the dump.” He’d taken them there to swim back in the day when you still could.

Mina pulled into Pelham Manor’s familiar entryway. Could it be only six months since she was there? Her last visit had been a week after Annabelle died. Mina had gone in to remove what remained of Annabelle’s few possessions. She’d given away most of Annabelle’s clothes. Donated her unused medications. And left with a few forlorn cardboard boxes.