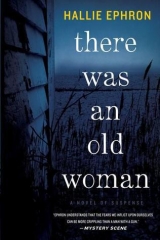

Текст книги "There was an old woman"

Автор книги: Hallie Ephron

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Dedication

For Jerry, whose love of old things inspires me

Acknowledgments

Stories come in fits and starts, and this one took its good sweet time to build, untangle, smooth, and interconnect. I have many people to thank for help along the way.

For technical detail and background, thanks to Kathleen Hulser, senior curator at the New York Historical Society; Clarissa Johnston, MD; Michele Dorsey, Esq.; and Shilo Hebert, RN. For inspiration, thanks to Jane Zevy, who survived her own fire in the Bronx, and Harlene Caroline, who let me visit her when she was cleaning up her mother’s house. Thanks to David Fitzgerald and Naomi Rand for helping me find the perfect geographic location to set the fictional neighborhood of Higgs Point—a real salt marsh with a view of the Manhattan skyline. The amazing history of the neighborhood was worth bonus points.

Thank you so much, Roberta Isleib and Hank Phillippi Ryan, my writing pals. Thanks, Anne LeClaire, for helping me decide where to begin.

Special thanks to my agent, Gail Hochman, and my editor, Katherine Nintzel. I could not be in better hands. Thanks to Danielle Bartlett, Shawn Nicholls, Seale Ballenger, and so many others at HarperCollins for the support, hard work, and good wishes that helped launch this book.

And thank you, Jerry Touger, for having my back and making it possible for me to have this life.

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Chapter Fifty-six

Chapter Fifty-seven

Chapter Fifty-eight

Chapter Fifty-nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-one

About the Author

Also by Hallie Ephron

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Mina Yetner sat in her living room, inspecting the death notices in the Daily News. She got through two full columns before she found someone older than herself. Mina blew on her tea, took a sip, and settled into her comfortable wing chair. In the next column, nestled among dearly departed strangers, she found Angela Quintanilla, a neighbor who lived a few blocks away.

Angela had apparently died two days ago at just seventy-three. After a “courageous battle.” Probably lung cancer. When Mina had last run into Angela in the church parking lot, she’d been puffing away on a cigarette, so bone thin and jittery that it was a miracle she hadn’t shaken right out of her own skin.

Mina leaned forward and pulled from the drawer in her coffee table a pen and the spiral notebook that she’d bought years ago up the street at Sparkles Variety. A week after her Henry died, she’d started recording the names of the people she knew who’d taken their leave, beginning with her grandmother, who was the first dead person she’d known. Now four pages of the notebook were filled. Most of the names conjured a memory. A face. Sometimes a voice. Sometimes nothing—those especially upset her. Forgetting and being forgotten terrified Mina almost more than death.

Mina found lists calming, even this one. These days she couldn’t live without them. Some mornings she’d pick up her toothbrush to brush her teeth and realize it was already wet. She kept her Lipitor in a little plastic pillbox with compartments for each day of the week, though sometimes she had to check the newspaper to be sure what day it was.

Now she started a new page in the notebook. At the top she wrote the number 151, Angela’s name, and the date, then she opened the drawer to tuck the notebook back in. There, in the bottom of the drawer, were her sister Annabelle’s glasses. Mina picked them up. The narrow white plastic frames had seemed so avant-garde back in the 1960s when Annabelle had decided she needed a new look. She’d worn them every day since. It was probably time—good heavens, past time—to throw them away, along with Annabelle’s long nightgowns, flowered cotton with lovely lace collars that she used to order from the Nordstrom catalog. Mina preferred short gowns that didn’t get all twisted around her legs when she turned in her sleep.

It was odd, the things one could and couldn’t throw away. She’d kept Henry’s New York Yankees cap, the one he’d worn to Game 5 of the 1956 World Series when Don Larsen pitched a perfect game in Yankee Stadium, and she wasn’t even a baseball fan.

And then there were the things you had no choice but to carry with you. She touched the side of her face, feeling the scar, raised numb flesh that started at her cheekbone and ran down the side of her neck, across her shoulder blade, and down into the small of her back.

Mina tucked Annabelle’s glasses back into the drawer along with her catalog of the dead. She picked up her cane and stood carefully. What she really didn’t need was to fall again. She already had one titanium hip, and she had no intention of going for a pair. She knew too many people who went into a hospital for a so-called routine procedure and came out dead.

She carried her tea outside to the narrow covered porch that stretched across the back of the house. After an icy, miserable winter and a soggy spring, it was finally warm and dry enough to sit outside. Her unreplaced hip ached, and the old porch glider screeched an appropriate accompaniment as Mina settled into the flowered cotton cushions she’d sewn herself. She took off her glasses to rub the bridge of her nose, and the world around her turned to a blur. She was legally blind without her glasses, but she’d been secretly relieved when the doctor told her she was far too myopic for that laser surgery everyone talked about.

“Oh, shush up,” she said when Ivory gave a plaintive mew from inside the storm door. “You know you’re not allowed out here.”

She put her glasses back on, and the porch and the marsh beyond snapped into focus. Mina rocked gently, taking in the view from Higgs Point, across the East River and Long Island Sound, and on to the Manhattan skyline. As a little girl, she’d watched from this same spot behind the house where she’d lived all her life as, one after the other, Manhattan’s skyscrapers had gone up. When the Chrysler Building poked its needle nose into the sky, she’d imagined that her bedroom was in the topmost floor of its glittering tiara. Then up went the Empire State, taller and without all that frippery at the top. It had been a dream come true when Mina, single “still” (as her mother so often reminded her) and just out of school, got her first job there.

Mina remembered wearing a straight skirt with a kick pleat, a peplum jacket, a crisp white collared shirt, and a broad-brimmed lady’s fedora that dipped down in the front and back, thinking that was all it took to make her look exactly like Ingrid Bergman. Movies, the war, and where you could find cheap booze were all anyone talked about in those days.

Two years later, the dream turned into a nightmare. For years after, the roar of an airplane engine brought the memory back, full force, and yet there she had been living and there she remained, right in the flight path of LaGuardia Airport. It was only after the long days of even more terrifying silence after 9/11 that the waves of sound as airplanes took off, one after the other, had become reassuring. All is well, all is well, all is well.

Right now, what she heard was a buzz that turned into a whine, too high pitched to be an airplane. Probably Frank Cutler, her across-the-street neighbor. Installing marble countertops or a hot tub. Making a silk purse or . . . what was it they called it these days? Putting lipstick on a pig.

At least he wasn’t rooting around in her trash or practicing his golf swing again. The last time she’d asked him to please, please stop using her marsh as his own personal driving range, he’d grinned at her like she’d cracked a particularly funny joke.

“Your marsh?” he’d said. Then added something under his breath. And when she politely asked him to repeat what he’d said, he told her to turn up her hearing aid. Ha, ha, ha. Mina’s eyesight might be fading, but her hearing was as sharp as it had ever been.

The buzz grew louder. Perhaps he was using a band saw. When he got around to adding dormers to the second floor, maybe he’d find the front tooth she’d lost playing under the eaves with Linda McGilvery when they were five years old. Linda, who’d been fat and not all that bright but awfully sweet, and who’d died of leukemia, what, at least forty years ago, though it still seemed impossible to Mina that she could remember so clearly something that happened so long ago. Insidious disease. Mina had been a bridesmaid at Linda’s wedding. Awful dress—

The sound morphed into a whinny, and then into whap-whap-whap, yanking Mina from a billow of pink organza. It was a siren, not a saw. And it was growing louder until she knew it had to be right there in her neighborhood. On her street.

As Mina hurried off the porch and up the driveway, the sound cut off. An ambulance was stopped in front of the house next door, its lights flashing a mute beacon. Sandra Ferrante lived in that house, alone for the past ten years since her daughters moved out. Two dark-suited EMTs jumped out of the ambulance and hurried across grass that hadn’t been mowed in months, pushing their way past front bushes that reached the decaying gutters and nearly met across the front door.

A third EMT—a man in a dark uniform who nodded her way—opened the back doors of the ambulance, unloaded a stretcher, and wheeled it up to the house. Had the poor woman finally managed to kill herself? Because as sure as eggs is eggs, drinking like that was slow suicide.

Mina stood there, hand to her throat, waiting. Remembering the ambulance that had arrived too late for her Henry. It didn’t seem possible that that had been thirty years ago. He’d died in his sleep. By the time she’d realized anything was wrong, he was stone cold. Still, she’d called frantically for help, as if the medics who arrived could restart him like a car battery. A massive pulmonary embolism, the doctors later told her. Even if he’d suffered it at the hospital, they said, he wouldn’t have survived. That was supposed to make her feel better.

Finally Sandra Ferrante was wheeled out. A yellow blanket was mounded over her. Mina found herself drifting closer, trying to overhear. Was she alive? Coherent?

Sandra lifted her head and looked right at Mina. She raised her hand and signaled to her. Asked the EMT to wait while Mina made her way over.

Up close now, Mina could see that the whites of her neighbor’s watery eyes were tinged yellow, and she could smell the sour tang of sweat and urine mixed with cigarette smoke.

“Please, call Ginger,” Sandra said.

Ginger? Then Mina remembered. Ginger was one of the daughters.

Sandra grasped Mina’s hand. Mina gasped. Arthritis made her fingers tender.

“Six four six, one . . .”

Too late, Mina realized Sandra was whispering a phone number. Mina tried to repeat the numbers back, but they wouldn’t stick. The EMT pulled out a notebook, wrote the numbers down, tore out the page, and handed it to Mina. She’d also written Bx Met Hosp and underlined it. Bronx Metropolitan Hospital.

“Please, tell Ginger,” Sandra said, pulling Mina close. “Don’t let him in until I’m gone.”

Chapter Two

The freight elevator of the Empire State Building descended slowly, bouncing a little as it landed. A maintenance worker pulled open the scissor gate and Evie Ferrante, her colleague Nick Barlow, and the team of four movers they’d brought with them emerged from the car—like clowns, Evie thought, spewing out of one of those tiny circus cars—along with a rolling platform loaded with tools and packing equipment. An officer from building security had escorted them down, presumably to make sure they took only the old jet engine that the Five-Boroughs Historical Society had been authorized to remove.

In this cavernous sub-subbasement, the ceilings were low and the lighting meager. Here none of the art deco architectural detailing of the building was present, just the structural bones. Evie had to watch out to keep from tripping over coal cart rails embedded in the floor or banging her head on the yellow pipes that snaked along overhead. A roach the size of a silver dollar skittered past her feet and into the shadows.

They followed the security officer into the core of the building, past massive support columns of bare concrete with veins where moisture had hardened into lime deposits. If she closed her eyes, the cool dampness and the smell could have convinced her that she was walking through ancient catacombs.

Evie’s heart quickened. There, sitting on the floor among some cardboard boxes, was a battered Wright Whirlwind engine, or what was left of the one from the B-25 bomber that had lost its way on a foggy Saturday morning in 1945 and slammed into the north side of the building. The wings and propeller had sheared off on impact. The plane itself had turned into a fireball, feeding on its own fuel and taking out offices on four floors.

Evie crouched beside the engine, savoring the moment. She was about to bring to light an artifact that no one had thought to look for. She hadn’t made history—that wasn’t her job—but she was about to preserve an important piece of it.

“Holy shit,” said Evie’s onetime mentor, Nick. “That’s it, isn’t it?” The expression on his face was of unabashed delight. “You did it. Congratulations.”

“Thanks.” Nick had been so incredibly generous to her. He’d been stoic if not supportive when she’d gotten promoted over him to senior curator, her academic degree trumping his many years of experience. “That means a lot to me, coming from you.”

The engine was round, about five hundred pounds of metal, five feet in diameter and caked with dust. With its center crank and rusting cylinders that radiated out, the thing resembled a miniature space station that had been through an intergalactic war. Upon impact with the building, the engine had been pulled right out of its cowling, and it had shot partway across the seventy-ninth floor before plunging to the bottom of an elevator shaft. It was miraculously still intact, not twenty feet away from where workers had hauled it from the elevator pit days after the accident.

It surprised Evie that so few people knew about the spectacular crash. Maybe it was because a few days later the United States had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

“This is so cool,” Nick said. He crouched beside her. “They’re just going to let us take it?”

Evie waved the release and letter of agreement she’d worked so hard to get. Finding the engine had been a reward for persistence. She’d been looking for artifacts to feature in the upcoming Seared in Memory exhibit, the first she’d curated solo, and it had occurred to her to wonder what had happened to the plane engines after the fire. From Alice Chen, a friend from college and now director of community relations for the Empire State Building, Evie had learned that not only did one of the engines still exist, it hadn’t been moved. Getting the building owners to agree to let the Historical Society feature the engine in the exhibit had taken months of diplomacy. It helped that one of the Historical Society board members was the wife of a senior partner in the property management company that ran the building.

While the movers got started assembling the polyurethane-sheathed cage that Evie had designed to protect the engine during transport, Nick set up lights and Evie started to take pictures. Of the engine. Of Nick standing over the engine, his arms spread to give a sense of scale. Of the closed door just beyond with white stenciled letters that read AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY. Of that door open, shooting down into the pit where the engine had landed. It must have sounded like a bomb exploding, a quarter of a ton of burning metal plummeting from more than a thousand feet overhead.

It took the rest of the morning to get the engine wrapped and hoisted onto a platform. By the time they were ready to leave, Evie’s arms and legs were coated with dirt and rust—and those were just the parts of her that she could see. She was glad she’d worn jeans and steel-toed work boots.

As they were bringing the engine up in the service elevator at the Historical Society, her cell phone vibrated. Maybe it was Seth. He’d promised her dinner at her favorite soup dumpling restaurant in Chinatown for a change. Handsome in a Colin Farrell kind of way, without the mustache, he and Evie had met at an auction. He’d outbid her for a gold-and-pearl tie tack that had belonged to Stephanus Van Cortlandt, New York’s first American-born mayor. It was a refreshing change to date someone who’d actually heard of Stephanus Van Cortlandt or knew that the pattern tooled on those gold cuff links was acanthus leaf. It wasn’t the worst reason she’d had to go to bed with a man.

The doors opened on the second floor, where the main exhibit hall was located. A minute later there was a chime. A text message. Evie fished out the phone.

The message was short and sweet. It was not from Seth; it was from her sister, Ginger, and it was so not what she wanted to see.

Chapter Three

It’s mom. Call me. xx Ginger

Why now? Not again. Evie knew she should return the call right away, and as she and Nick entered the Great Hall of Five-Boroughs Historical Society, pushing ahead of them a platform truck with the B-25 Wright Whirlwind engine wrapped up on it like a gigantic pastrami sandwich, that’s what she was intending to do. But her boss’s reaction to their arrival sidetracked her.

“Wow. Is that what I think it is?” Connor Kennedy’s familiar voice boomed behind her. A moment later, he was in her space and she could smell his cologne and cigarette breath. He stood absolutely still and silent, staring at the engine. Moving the thing had eaten up a good chunk of Evie’s budget, but judging from Connor’s reaction, it had been worth it.

“So this is going to be sensational,” he said, doing a 360 and surveying the disarray in the exhibit hall with apprehension. “We are going to make it, aren’t we?”

“Of course we’ll make it. We always do,” Evie said, sounding more confident than she felt.

The parquet floor of the Great Hall was awash in packing crates. The other two members of Evie’s small staff were assembling bases and plexi mounts for the installation. The museum’s resident electrician was drilling into the wall and wiring one of six massive flat-screen monitors. One of the janitors was sweeping up wood and plaster dust with a wide push broom.

Outside, beyond a row of narrow two-story arched windows, bright yellow banners for the upcoming exhibit snapped in the breeze. Dramatic red-orange letters on them read: SEARED IN MEMORY. Below that and smaller: June 10–November 17. Just three weeks until it opened.

Evie could envision the room, silent and cleared of debris. Each of four historic fires would have its own timeline and photographs, audio and video. Artifacts she’d culled from their own collection and borrowed from others would be mounted, lit, and documented. Together, each grouping would tell its own story.

She walked Connor through the half-finished installations. Greeting visitors and already in place was a magnificent red-and-black steam-powered pumper like the one used to fight the Great Fire of 1776 that destroyed the Stock Exchange and much of lower Manhattan. The next section, commemorating the fire during the ugly 1853 Civil War Draft Riots, would feature blowups of inflammatory broadsides (“We are sold for $300 whilst they pay $1000 for negroes”) that stoked passions so much that anyone with dark skin risked being chased through the streets, beaten, and even killed. One of her favorite pieces in that section was a long speaking trumpet, the kind that would have been used to shout orders to firefighters over those five hellish summer days when the city burned.

Another section remembered the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, arguably the saddest of all time. In the center was a raised platform where they’d set a battered fireman’s net that couldn’t save the young, mostly immigrant women who’d thrown themselves from the windows of the upper floors of the Asch Building. Foam-core mounted photographs, showing views of the devastated factory interior filled with charred sewing machines and coffins lined up tidily on the floor like fallen soldiers, were already on the wall. Something about the photographs from that one always did her in, filling her head with the gut-wrenching smell of smoke, a smell seared in her own memory.

The list of the 146 who died in that fire was particularly heartbreaking. Mary Goldstein had been only eleven; Kate Leone, fourteen; most of the rest were in their teens and early twenties. A few of the bodies remained unidentified a hundred years later.

Journalists back in those days were allowed, encouraged even, to write unabashedly emotional prose, and Evie had selected a quote from a reporter’s viscerally melodramatic eyewitness account:

I learned a new sound—a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk. . . . Thud-dead, thud-dead—together they went into eternity.

Thud-dead, thud-dead, together they went into eternity. The elegiac passage, more poetry than prose, moved Evie profoundly. She couldn’t imagine today’s Daily News or New York Times printing anything like that.

As she finished showing Connor around, taking notes on his suggestions for ways to tweak the displays and adding to her to-do list, she was reminded what being senior curator meant. Much as she might delegate, she was the one responsible for seeing that every little detail, down to the spelling on the signage and the training of security guards, was done properly and completed in time for the opening gala.

When Connor stopped to chat with Nick, who was carefully cutting away the protective covering they’d built around the airplane engine, her phone chimed again. Evie reached into her pocket and turned it off.

Evie meant to call Ginger back. Really, she did. But she got pulled into one meeting and then another. Two hours later, eating a midafternoon granola bar instead of lunch, she was back in her office, the door closed, trying to finish editing transcripts of eyewitness accounts of the fires before the voice-over actors arrived to record them. When her cell phone rang, she recognized the number with its Connecticut area code and for only an instant considered not answering it.

“Didn’t you get my message?” Ginger started right in.

“I’m sorry. I was tied up. I was going to call back but . . .” Evie bit her lip and took a breath. She didn’t want to make it sound as if her time was more important than Ginger’s. “Listen, I am sorry. I should have called you right back. How’s Ben? The kids?”

“You know that’s not what I called about. It’s Mom.”

“Again,” Evie said, at the same time as Ginger.

Even though there was nothing even remotely funny about that, and even though she knew that laughing was wildly inappropriate, Evie couldn’t stop herself. A moment later, Ginger was laughing, too, and that made Evie laugh even harder until she nearly dropped the phone and had to sit down to keep from peeing in her pants.

At last, laughed out and gasping for breath, she wiped tears from her eyes. “So how bad is it?”

“She fell and dislocated her shoulder this time. And I guess it was a while before she managed to call for help. Mrs. Yetner left me a message. She’s at Bronx Metropolitan. The shoulder’s not all that serious. It’s everything else that’s the problem.”

Evie thought she had a pretty good idea what that meant. “You saw her?”

“Just for a few minutes. She was barely conscious. Stabilized is what the doctor called it.”

“Stabilized,” Evie said. Did that mean she was going to get better? Or was she going to stay as sick as she was?

“On top of everything else, the EMTs who pulled her out alerted the health department. They sent an investigator over to the house. They say the place is a health risk. If it gets condemned—”

“Condemned? You’ve got to be kidding.”

“I guess it’s gotten that bad. If Mom can’t go back, she won’t have anywhere to go and, well . . .”

Evie finished the thought: then she’ll have to move in with one of us. Ginger couldn’t be thinking that Mom could move into Evie’s one-bedroom apartment. Ginger was the one with a house. A guest room.

“Evie, I can’t always be the one,” Ginger said.

“Why does it have to be either of us? She’s a grown-up.”

“She’s never been a grown-up, and you know it. And now she’s in the hospital. All alone.”

Right. Alone because one after the other she’d pissed off the friends she and their father had once had. Alone because she hadn’t been able to hold a job for years. Thinking about her mother made Evie furious and unbearably sad at the same time. Talking to her was even worse. And seeing her?

“No way.” Evie looked down at the pile of audio scripts, sitting on her desk, deadline looming. At her to-do list that only seemed to grow longer, no matter how much got checked off. “Come on, Ginger, I can’t take time off right now. This exhibit is my first. It has to be great. It’s opening in three weeks, and there is still so much to do. I promise as soon as I’m done, the very minute it opens, I will pitch in.”

“Pitch in?” There was a long silence. Then Ginger sniffed, and Evie realized she was crying.

“Ginger?”

“I don’t want you to pitch in,” Ginger said, her voice a harsh rasp. “I want you to take charge.”

“I will. I will.”

“And not in three weeks. Now.”

“But—”

“Surely you’re not the only person who works over there. No one is irreplaceable.”

“I . . . I just can’t. I’m sorry.”

“Sorry? Sorry? Sorry doesn’t cut it. I have a life, too. In case you’ve forgotten”—Ginger’s voice spiraled up—“I’m taking classes. The paralegal certification exam is in four weeks. Ben is working two jobs. Lisa’s got dance classes and soccer practice. And . . . and . . .” Ginger blew her nose. “And why is it that every time, every fucking time she crashes, I’m the one who has to drop everything?”

There was a knock at Evie’s door, and Nick stuck his head in. He pointed to his watch. The voice-over actors must have arrived, which meant the meter was ticking—they charged for their time whether the script was ready or not.

Evie put up her hand, fingers splayed. Five minutes. Nick nodded and disappeared.

Ginger was saying, “—can’t do it, Evie. Not this time. I’m tapped out. Completely tapped out. It’s your turn. I’m sorry, but this time you don’t have the luxury of cutting her off unless you’re planning to cut me off, too.”

In the silence that followed, Evie could hear the massive schoolhouse clock behind her desk tick-tick-ticking. The last time she’d seen her mother, they’d arranged to meet for brunch at Sarabeth’s in Manhattan, halfway between Evie’s Brooklyn apartment and her mother’s house at the edge of the Bronx. They were supposed to meet at noon. When Mom hadn’t shown up, and hadn’t shown up, Evie had tried calling her. No answer at home. No answer on her mother’s cell.

As minutes ticked by, Evie had gone from being furious with her mother, late as usual, to being hysterical and in tears, imagining the worst as she tried to flag a taxi to take her to Higgs Point. Good luck with that. Three cabs refused before she snagged one that would.

When she got to the house, her mother was passed out in front of the TV. “I must have lost track of time,” she said when Evie finally managed to rouse her. Later, as Evie made an omelet, she caught her mother sneaking some vodka into her orange juice. She’d tried to talk to her mother about her drinking, but her mother flat-out denied it, like she always had. Evie was the delusional one, she’d insisted, then screamed at Evie for butting in and trying to run her life.

On the bus and subway ride home, Evie had seethed with anger. That was it, she promised herself. Never again. If her mother couldn’t stop drinking long enough to get herself to Manhattan for a lunch date with her daughter, wouldn’t even admit that she drank, then to hell with her. Evie was finished. Finished taking care of her. Finished talking to her even.

After that, Evie stopped returning her mother’s calls. Screened out her e-mails. Maybe if she cut her off completely, she told herself, her mother would get serious about drying out. But the truth was, it was a huge relief to sever the cord, to allow herself to give up responsibility for caring.

That had been months ago. And now Ginger was finally fed up, too, but she couldn’t walk away. She wasn’t wired that way.

“Okay, okay.” Evie couldn’t believe she heard herself saying it. “I’ll take care of it. I’ll go up to the house tomorrow and start getting things cleaned up. I’ll go over to the hospital in the afternoon. Stay—”

“And stay? Oh, would you?”

“Just for the weekend.”

“But—”

“Then we’ll see.” Evie swallowed. “And you’re right. It is my turn.”