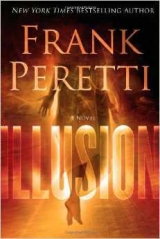

Текст книги "Illusion"

Автор книги: Фрэнк Перетти

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

chapter

7

The black Lexus entered the parking lot of Christian Faith Center with the inertia of a yacht easing into a marina, rolling up the first row of parked vehicles, then down the next row, then up the third, then down the fourth, chrome wheels lazily rotating without blur, brake lights mostly on, the turning engine barely audible. There were plenty of empty parking spaces by about the seventh row, but the Lexus didn’t go there, not without its occupants viewing every occupied space first.

The driver called himself Mr. Stone, an apt name for a man whose face looked like he just woke up from a nap on a bed of pea gravel. He was blond, masked behind black sunglasses, and well dressed in black. He drove with his left hand, and with his right hand he held a digital camera propped in the open window, discreetly recording every license plate of every vehicle.

Mr. Mortimer, his associate in the passenger seat, made a near opposite: handsome, Mediterranean, dressed in expensive black. He was also using a digital camera, capturing every license plate on his side, the back ends of the cars reflecting and distorting in the lenses of his designer shades.

The Lexus moved steadily, efficiently, recording every vehicle, and finally came to rest in a parking space of its own. Stone and Mortimer got out, put on a personable, respectful demeanor, and headed for the church doors.

A nice lady with a white corsage greeted them in the foyer and handed each a folded bulletin: In Loving Memory of Mandy Eloise Collins. A voice came through the open doors to the sanctuary, what sounded like a testimonial: “… always remember her wonderful sense of humor, her way of finding the up side to just about anything …”

They smiled at the lady, then strolled to a large display, a collection of photographs from the life of the deceased set up among bouquets of flowers in baskets, stands, and vases. Memories. Great moments. The men smiled, nodded to each other, pointed and acted in every way like two old friends of the deceased now remembering how great it was to know her. “Hey, remember that?” “She looks great, doesn’t she?” “Now, that illusion baffled everybody!” “Is that her mom and dad? She really takes after her mother, doesn’t she?”

And with an appearance of fondness, love, and whatever else would make the act seem natural, Mr. Mortimer took out his camera and started recording the photographs: Mandy the teenager, straight-haired and tie-dyed; Mandy no older than twelve, sitting between her mom and dad with a new puppy; Mandy in her high school talent show performing the Chinese Sticks illusion; Mandy at eighteen, in jeans shorts and One Way T-shirt with four white doves perched on her arm.

Mr. Stone made his way through the door into the sanctuary. Neither he nor Mortimer was a churchgoer, but the venue was not unfamiliar, comparable to a theater or Vegas showroom without the lavish theme and decor. Pews were arranged in a fan-shaped room sloping toward a central stage set up for a band and possibly a choir. On the back wall was a large cross and above that the words “Jesus Is the Same Yesterday, Today, and Forever.” At front center stage was a diminutive Plexiglas pulpit where the minister delivered his sermons. At the moment, no one stood there. The voice was coming from an attractive young woman down in front, probably a friend in show business, speaking into a wireless mike: “… and I will always smile and laugh when I think of Mandy. I know she’d want it that way.”

She set the mike on the edge of the stage and then bent and gave a hug to a silver-haired man in the front row, recognizable as Dane Collins, the bereaved husband. From this position in the back of the room, Stone could catch only a glimpse of Collins’s profile before the man looked forward again, but Stone determined to get close enough, perhaps during the reception following, to study the face and get to know it.

A video began to play on two large screens on either side of the stage. Stone gave it his full attention because it was a collection of scenes from Mandy Collins’s life. The first clip was a grainy, scratchy film—the original had to be Super 8—of Dane and Mandy, two kids barely in their twenties, performing on a truckbed before what appeared to be a company picnic, pulling white doves out of sleeves, from under silk handkerchiefs, from an audience volunteer’s hat, out of nowhere. Stone noted Mandy’s hair in curls, medium length, and her figure youthful, slender.

As the video played in the sanctuary, Mortimer continued recording photos in the foyer and noting when they may have been taken: Dane and Mandy’s wedding in June 1971—beautiful bride, long hair in graceful waves and lacy ribbons; Dane and Mandy with his folks and her father, 1975, Mandy looking about the same.

Stone edged halfway down an aisle and found a seat as he watched a grainy VHS recording from somewhere in the 1980s: Mandy in an evening dress, hair magnificently coiffed atop her head and jeweled earrings dangling, drawing laughs from an audience as she fumbles with two narrow tubes, a glass, and a pop bottle on a table. “Now, you put this tube over the glass and this tube over the bottle and they will magically trade places …” The tubes go out of control, producing a bottle where the glass should have been “… Oops! You weren’t supposed to see that! …” then producing bottles, bottles, and more bottles. “No no no, let me try that again!”

Mortimer recorded a 1990 photo of Mandy in jeans, shirt, and baseball cap with her aging father and two llamas. Mandy was thirty-nine at the time and still looked great: big smile, engaging eyes, neck-length haircut.

Somehow the video historian found a clip of Dane and Mandy appearing on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.That had to be prior to 1992. Mandy could have been entering her forties or still in her late thirties; it was hard to tell.

“Now, I’ve seen you do this,” Carson was saying, sitting behind his host’s desk and holding a Rubik’s Cube. “And of course there’s a magician’s way of solving it instantly, a magical effect, but you can solve a real one—”

Mandy, in the chair closest to Carson, gave a playful nod, “Uh-huh,” which got the audience stirring and squealing. Dane sat in the next chair, exuding full confidence. Ed McMahon sat to his right.

“How long does it take you?”

“Depends on my fingernails.”

“Well, how are they?”

She looked. “About right.”

“Less than a minute?” Carson offered her the cube.

Mandy rolled her eyes, but the audience cheered and goaded her and she took it from him.

Carson, a magician himself, assured the audience there was no trickery involved; the cube was genuine. He said “Go” and clicked a stopwatch, the audience counted down as her fingers became a blur, and she held up the solved cube, every side totally one color, in thirteen seconds. Not a world record, but good television.

Mortimer was especially interested in the family photos, the informal shots of Mandy the gal: Mandy and Dane on a fishing trip, holding some admirable salmon they’d caught; on a bike trip, although the helmet and sunglasses made Mandy’s features hard to see; a later promo photo commemorating Dane and Mandy’s thirtieth year in show business presented plenty of detail: the laugh lines around her eyes, the subtle lines in her face, the glint of white in her blond hair. The big-eyed smile was still there, just as in the photos of Mandy at eight, at twelve.

The video was a mother lode of information showing facial expressions, mannerisms, vocal tones, reactions. In an HD clip from only a few years ago, Dane was levitating Mandy a good twenty feet above the stage at the MGM Grand when she suddenly woke up from her magical hypnotic state, looked at the stage lights, and observed, “Boy, talk about dead bugs!” and produced a portable hand vacuum from nowhere. Her playful smile came through the video as well as it must have reached the back rows in that theater, and the rest of the illusion was a well-timed, well-planned catastrophe for her husband.

Mortimer finished up by surreptitiously recording the signatures in the guest book. It didn’t take long.

Stone finished up by requesting a copy of the video from the tech in the sound booth.

They stayed for the reception afterward, but only long enough to apprise themselves of Dane and Mandy Collins’s circle of friends and peers. They slipped out quietly, before they could be noticed enough to be introduced to Dane Collins.

chapter

8

Dane limped off the plane at Spokane International and found this once-familiar piece of ground where Mandy grew up was suddenly, strangely unfamiliar. He and Mandy came to visit regularly until her father passed away in ’92. After she sold the ranch in ’98 they still returned simply because it was Idaho and Mandy loved Idaho. When they came here recently to scout out a new place to call home, it felt like home.

But this trip felt entirely first-time.

He’d bought one ticket, packed one bag, carried only one boarding pass. There was no one to wait for while going through security and no one to wait for him. He had no one to meet in any particular place when he came out of the restroom and no one to keep in touch with by cell phone; he bought only one Starbucks coffee and a blueberry muffin for only himself. There was no one to watch their stuff while he walked around and no one to walk around while he watched their stuff; he went through doors first with no one to open them for.

While waiting for his one bag to slide onto the carousel, grief overcame him as it often did, on a schedule all its own, unpredictable, unavoidable. Maybe it was standing here alone, picking up one bag. Maybe it was the memory of her calling her dad from this very spot to let him know they’d arrived. Maybe there was no reason at all. Grief just came when it came, worked its way through, and receded quietly until the next time. That was the way it worked.

On the other side of the carousel, Mr. Stone and Mr. Mortimer stepped through the waiting bodies to pluck up their bags. They had shed the cool, pretentious look of Las Vegas and put on duds that said laid-back, outdoorsy Idaho, but they weren’t feeling it yet.

Dane’s rental car had a GPS. He punched in the address of the Realtor in Hayden, Idaho, and the route popped up on the screen. I-90 most of the way, very easy. He remembered it from the last time they were here.

The last time, theywere here. Theywere on their way to close the deal when the wreck happened.

“Well, let’s get it done,” he said to himself and to her as he turned the key in the ignition.

Mandy had had a better room the past few days, thanks to Bernadette, who recommended it, and Dr. Lorenzo, who okayed it. It wasn’t a whole lot different from the room she had in intensive: the bed was a mattress on a wooden box with no metal parts, the light fixture was a breakaway design that would not bear the weight of anyone trying to hang herself, and the door could be locked from the outside only. Two nice differences were that the bed had no restraints installed and that Nurse Baines and Dr. Lorenzo saw no need to lock the door—as long as Mandy kept it open and gave them no cause to decide otherwise. So she had moved up in the world, sort of, with a bit more freedom and trust, but at the same time, anyone standing at the nurses’ station could take just a few steps away from the counter and see right into her room.

Well, it was a hospital. What didn’t they know about her?

She twisted and buried her face in the pillow. Was it really crazy to be Mandy Whitacre? Could she, should she ever, everallow herself to think that her entire life, everything she had ever been and known, was only a delusion? How could that be? She couldn’t have made up her mom and dad, the schools she went to, the friends she had, the ranch, their church, getting saved and baptized, raising her doves, learning and showing her magic, grilling hamburgers in the backyard with the youth group, taking classes at NIJC. All of that was real and every day was a new discovery, something she never thought up before she got there. Life happened to her and she lived it.

She sighed. Okay, then. She really was Mandy Whitacre, and nobody was going to change that.

So what about waking up in the year 2010? It was easy to make up a wild sci-fi explanation, something like an Outer Limitsepisode: some wacky scientist at the fair was showing off a time warp generator and she’d accidentally walked into its vortex and been transported forty years into the future. It made a great explanation. Everything she was experiencing fit right into it. The only problem was, it was loony above loony.

So, could it all be a delusion? Could she really have imagined and made up things like a CAT scanner, computers, cell phones, flat TV screens, Google (she still didn’t know what that was), and little square plastic things that put out music without playing a tape or a record? She couldn’t have imagined Dr. Angela and June and Dr. Lorenzo and stony Nurse Baines. She couldn’t have conceived of the questions they asked and the words they used, and how her whole world could shrink down to this sterile, hypercontrolled cluster of little rooms.

Or … could she? She’d always had a creative imagination. She liked making up stories. Had she slipped a gear and put herself into a story she was making up? Maybe she’d slipped a gear and put herself into her own magic trick, the queen imprisoned in a stranger’s pocket.

She rolled onto her back and stared at the flat, white ceiling, featureless except for the hangingproof light fixture. Could she be imagining that light fixture? Was it part of a delusion? It looked real enough. How could she tell the difference?

Well, she would start with what was real. Daddy was real. The ranch was real. Maybe she was wrong about the dates, but she knew where home was, and that would be the place to sort all this out—not here. In this place, she was crazy; at home, she was Mandy Whitacre and nobody there would look at her funny or jot down little notes or make her take pills. And she didn’t have to be afraid. If she could get home, she could have all the time she wanted to work out this mess.

With her eyes focused on the bare white ceiling above her—in other words, on nothing in particular—Mandy’s mind drifted over memories of homecomings throughout her life: getting off the school bus and walking along the white paddock fence that bordered North Lakeland Road and always noticing the height of the hay in the field: short, taller, ready, then mowed short again; short, taller, ready, then mowed short again. It was a long walk when she was in the first grade wearing a dress, tights, and Mary Janes. The walk was shorter when the hayfield became the llama pasture and she was wearing fishnets and a skirt to her midthigh. By the time the white fence was replaced and the llama pasture divided off for some horses, she was in an embroidered blouse, flared jeans, and sandals and didn’t think about the distance; she was driving a Volkswagen Beetle and too busy thinking about everything else.

The mailbox grew a little more rust each year and went through several sets of reflective, stick-on letters and numbers: WHITACRE, 12790. From there the gravel driveway with the potholes and rain ruts went up a hill between two pastures toward the big white house with the gabled roof and wraparound veranda. Every time she walked or drove up that driveway her line of sight would clear the crest of the hill and she would see the dove house Daddy made for her out of a secondhand tool shed they brought in on a trailer, then the horse barn, and across the alleyway from that, the smaller barn for the llamas. The last thing to peek over the brow of the hill would be Daddy’s machine shop, with the old tractor parked alongside …

Dane wore his sunglasses to drive, checking out the city of Spokane as he drove through on I-90. On the left was downtown, with its classic brick buildings and modern vestiges of the 1974 World’s Fair. To the right, on a hill overlooking the city, were the hospitals: Shriners Hospital for Children, Deaconess Medical Center, Spokane County Medical Center. He looked back to the freeway. He’d had quite enough of hospitals, they only brought back all the memories … although the Spokane County Medical Center caught his interest for no particular reason. He looked back once.

Above Mandy, the ceiling went blue, like a cloudless summer sky. She blinked. Still blue. Maybe she’d been staring at all that white too long. Her eyes fell toward the wall …

She saw—she didn’t think she was imagining it—a white paddock fence running along a two-lane country road, the uncut grass obscuring the bottoms of the posts and reaching past the first rail; a gravel-lined ditch between the fence and the road shoulder; a robin perching on a fence post.

She did a double take, then sat halfway up, resting on her elbows. Her lazy stream of memories had come to a close at the old tractor next to the machine shop. This white fence was here without her remembering it, and so was the robin until it flew away.

She tried to relax the very interested look from her face as she peered past the white fence and out the doorway to the nurses’ station, now sitting in the high grass of the pasture.

Freaky. Not scary, freaky. How was her acting? Convincing? She couldn’t let them find out about this!

Rolling onto her side and passively resting her chin on her hand, she took in the double exposure, or more like a double location, two places sitting right on top of each other. Three aspens with white-striped trunks and quaking green leaves stood in the community area—she could see them through the wall.

It was all so lovely and so much what she wanted to see that she was captivated, not frightened. She lay there quietly, motionless for several minutes, just watching the grass wave in the breeze and the robins, blue jays, and finches flit about in search of worms and wild seeds.

The vision faded. The blue sky surrendered to the white ceiling, the grass faded from the nurses’ station; the white fence and the white-striped aspens dissolved as the walls of her room became solid … almost. Maybe it was Mandy’s eyes not used to the darker room after being “outside,” but everything in the room looked dimmer, and the edges of things—the edge of the doorway, the edge of the counter at the nurses’ station, the edges of Tina, the nurse now standing there—were shimmering, as if Mandy were watching them through little heat waves.

Things sounded different too, muffled, as if she had her hands over her ears, which she didn’t, with a low, rumbly hum like a big appliance whirring away somewhere deep under the floor. And there was a smell—pungent, like singed hair, like something burning. She crinkled her nose.

Trying to relax and not look weird in any way, she sat up and swung her feet down to the floor. The floor was cold linoleum, but now it felt soft and warm, as if her feet had come to rest on a thin, fuzzy carpet. Looking down, she marveled at how the floor gave a little under her feet, as if it had turned to rubber.

Shelooked fine, not dim, not wavering. The edges of her legs, arms, and feet were sharp and clear, and stood out in stark relief against everything else. So she was there, but everything else was only sort ofthere.

Well. Maybe this was good news. Maybe it meant she was real and the room, Tina at the counter, the hospital—and Dr. Lorenzo and Dr. Angela and Bernadette and the tables and chairs and pills and yucky sandwiches and scrubs—might not be.

She could live with that.

But she’d better be careful.

She reached for her slippers—they looked like they were submerged under weak, wavy tea, so she reached just an inch at a time until she actually touched them. They were soft and spongy, but didn’t dissolve her hand or zap her with a lightning bolt. She took hold of one and it blinked on, crisp and clear, as real as she was. The other slipper did the same. She slipped them onto her feet and, looking casual, rose from the bed. The doorframe gave under the pressure of her hand, warping like an image in a fun house mirror. She withdrew her hand, and it wobbled back into shape again. Nurse Tina kept working behind the counter and didn’t look up. Mandy waved at her, smiling.

Tina didn’t seem to notice.

Nurse Baines jostled behind the counter, digging out some charts and looking like she hated it. The nurses’ station was shimmering like a mirage, and so was Nurse Baines.

Well, Nurse Baines was no game player, no sir. If there was one way to find out for sure … She had to hurry, before she woke up and the dream was over.

She didn’t rush but she did stride briskly up to the counter. “Nurse Baines?”

Nurse Baines looked at Tina and asked, “What happened to Forsythe?”

“Who?” Tina asked.

That was a perfect response to make Nurse Baines angry. “For. Sythe. The chart I asked for?”

“I asked Carol to make a copy.”

Mandy jumped in place. She waved a little wave.

Well, Nurse Baines could have been ignoring her.

“Nurse Baines!” Mandy called.

“Well, you see this?” Nurse Baines slapped a red filing folder on the counter. “When you get that copy, it goes in here and the folder goes back on the shelf—under F. We clear?”

“Yes, ma’am!”

The electronic lock whirred and the big double doors swung open. Clive, from billing, came in with some paperwork, tossed it on the counter, then turned and went out the doors while they lingered in a programmed pause—and Mandy stood and stared down that long, open hallway illuminated with sunlight through a row of big windows. Through those windows she could see the tops of trees lining the parking lot and some of the city beyond that, the whole, big, outside world. The doors began to swing shut. Three-quarters open. Half open.

Mandy stood there. Oh, that beautiful hall! That beautiful outside world!

The ranch. Home. Daddy.

She looked at Nurse Baines. At Tina. Were they really ignoring her? She could see Tina’s coat on a hook in an alcove near the doors.

The doors were still closing, closing …

She made a timid movement toward the alcove …

Oh, God help me!She grabbed for the coat. It was wavy like everything else, dim and fuzzy as if Mandy were seeing it through a tea-stained window. She grabbed hold. The coat felt like warm plasticine in her fingers. She pulled it toward her—

The coat broke through the tea-stained window and shimmering heat waves and became clear, crisp, and real in her hands.

Almost closed.

“I’ll bring it back, I promise!” she called, dashing through the narrow opening a millisecond before the doors would have clamped on her foot.