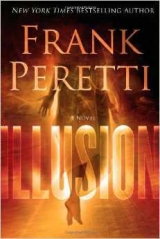

Текст книги "Illusion"

Автор книги: Фрэнк Перетти

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

chapter

49

At 5:00 A.M., March 25, Parmenter was at the command console of the Machine, running simulations of what might be to come and checking the readings that resulted. He could tell Mandy was still asleep. The monitors were void of activity and, apart from maintaining Mandy’s secondary timeline, the Machine was at rest, allowing him a limited but sufficient access to its functions. This would be his only opportunity.

At 5:20, having double-checked his times, readings, and figures, he weighed himself, holding the box containing his notes, printouts, and hard drives. He’d lost one pound during the night, probably due to dehydration and elimination.

At 5:50 he accessed the Machine. The processing time was snail-paced but he got the input prompt he wanted and entered 14:24:09, two-twenty-four and nine seconds in the afternoon, today.

He added a book to the box and weighed himself and the box again. Within limits.

At 5:54, based on a conversation with Dane regarding when Dane planned to get up that morning, he entered some presets to initiate a function at precisely 6:00 A.M.

At 5:55 he went up the steps to the glass enclosure and, for the first time since Mandy’s reversion, opened the door. The stench of the bloodied sheet brought back the gruesome memory of September 17, but Parmenter’s disgust was mixed with a scientist’s regret. To put forward a theory, these molecules staining the sheet—skin cells, fluids, blood—did not revert with Mandy because they no longer composed something living in the present and possibly because they were not part of the arrangement of molecules that composed the living Mandy in 1970. Under any other circumstances he would have devoted himself to testing the theory and confronting the plethora of riddles and questions that remained, but that was only the scientist side of him. The human side, prevailing, could only do the right thing.

He stepped inside the enclosure, closing the door behind him, then sat on the bench holding his box of knowledge and secrets. He waited.

At 6:00 A.M., Dane’s alarm jolted him. He reached over and shut it off, then sagged back upon the pillow, waking up to the burden of this day and the visceral wrenching that left him only during his few precious hours of sleep.

Oh, Lord, is this day really happening? It’s the stuff of bad dreams, not real life. If I don’t get out of bed, maybe I’ll wake up for real in a little while.

Such words, such thoughts. This day had to happen, as unavoidable as life always was. He flopped over on his back and stared at the real ceiling fan above him, still there just like everything else. He got up and got started.

At 06:00:00, March 25, the Machine awakened, the enclosure glowed an eerie blue, the interdimensional core beneath the bench hummed with energy. Parmenter sat still, letting the program run, recording his mass, his exact location, and exactly when in the course of time this event occurred. After five seconds, the program completed, the Machine went dark, and Parmenter found himself in a strange, nontypical state of mind: he’d just done the last thing he could have done.

By 7:30 A.M., Andy’s stage crew was onsite, giving the bleachers a final cleanup and dressing up the stage, placing a few more artificial plants, trees, and stones to suggest a medieval, fairy-tale forest and replacing the burned trees around the volcano with fresh ones.

The sound man was running the sound effects and music cues, making sure they all lined up with the script, which they did. The ground-shaking rumble of a volcano, the explosive thud of a pod landing in the volcano’s crater, the whoooosh!of a hang glider circling to earth, all playing against a thrilling musical sound track, were great people attractors. Curious tourists and passersby paused at the ribbon barriers around the parking lot to see what was going on, and from there could read the splashy signage telling them there would be a spectacle on this very spot at two that afternoon.

On the roof of the Orpheus, the three-man hang glider crew gave Mandy’s glider one more preflight while monitoring the wind sock on the roof and the wind sock on the ground. So far so good, but even mild breezes boiled and swirled around and between the high structures on the Strip, and if the winds got too intense, Mandy would have to fall back on her rappelling routine.

One block away, Preston and his crew unfolded a sixty-foot platform that spanned the top of one truck and trailer, and on top of this they carefully laid out a foot-thick, sixty-foot-long cluster of fine fibers bound with Velcro loops. They had a wind sock as well, installed on the other truck’s radio antenna. Right now it barely stirred, but that could change as the day warmed up.

By 8:00 A.M. Dane had made the rounds checking on everything and now stood with Emile on the stage, “preflighting” the pod prior to hoisting it aloft and second-guessing his own design. I could have … maybe I should have … this is a little awkward, I could have put it over here …

But the design, as it was, was sound and the escape hatch was functional. Given that, the greatest danger today, if any, would be human error.

Which put it all on Mandy, and if there’d been an easier way he would have taken it.

At 9:00, Mandy arrived with Seamus, and while Seamus oversaw everything and took videos, she squeezed into the pod for one last go-through with Dane and Emile.

While she squirmed inside the pod, testing the petal doors, shedding the shackles and cuffs and tripping the escape hatch, she remained detached and clinical, never suggesting through tone or action that there were any galactic-size issues overshadowing this whole day, never showing that there had ever been or would ever be a love between herself and Dane, the clearest and farthest opposite of the truth. Dane followed the same script, to the point that she hungered for assurance, for one moment when they could say something … anything.

Maybe when it was over. For now, with the clock ticking, there was only the Grand Illusion—the timing, the devices, the costume change, the winds, getting it right.

And, of course, there was Seamus.

At 10:05, Seamus called Mandy, Dane, and Emile together and suggested they run one more test flight of the hang glider. Mandy was agreeable, but given that it was the surprise ending for the stunt and that people were beginning to linger around the perimeter of the parking lot, they decided to forgo it. Everything else was ready. The pod was safe and sound with the stage crew keeping an eye on it, ready to hoist into position at the top of the show.

At 11:23, Parmenter and Loren Moss were seated at the command console, monitoring the readings as they had been doing for days on end, and of course, until the Grand Illusion actually took place, there wouldn’t be much to monitor. At the moment, Mandy’s readings were predictable: quivering, fluctuating, exerting small flashes and distortions on the space-time fabric as if she were troubled and nervous. Parmenter and Moss found it easy to stray to other topics of conversation. Two staff members, by now indifferent to this whole monotonous process, sat at the table eating some fresh doughnuts and talking about sports.

At 12:00 noon, as the signs and the newspaper and television ads all promised, the ribbons around the parking lot came down and folks were allowed to drift in, find a spot in the bleachers, get comfortable, and wait. They arrived in small trickles at first, but there was no doubt the trickle would turn to a flood as two in the afternoon approached.

Along with the people came the news trucks. Vahidi had seen to that. Mandy’s Grand Illusion would be broadcast live on two stations and on the evening news on all of them, which was the greatest free publicity the Orpheus Hotel could ask for, and all the more reason to give them a real show.

At 12:30, Moss and Parmenter availed themselves of microwaved sandwiches from the kitchen and nibbled at them as they watched the monitors showing nothing interesting. One of the staff had brought in a television so they could watch the live broadcast, but right now the station was carrying a network show, six political pundits sitting around a table interrupting each other. When Parmenter turned down the sound, no one complained.

“What are we expecting, anyway?” Moss finally asked.

Parmenter had to think to come up with something. “I suppose we could be seeing the Machine approach its limits. From what I understand, this is going to be one heck of a stunt.”

“Ohhh, that’s for sure.”

Moss’s tone was a bit elevated when he said that. It made Parmenter wonder what he meant.

Moss piped up, “Bigger than what we’re planning in the desert?”

What?Parmenter put up a hand of caution. “Not here.”

Moss looked at the two staff members finding something to do at another station. “They can’t hear us.”

“We don’t discuss it here.”

“Well … maybe in cloaked terms …”

“Not in any terms!”

“But it does look promising.”

Parmenter answered, if only to end the topic, “Yes. I would say the theory’s working.”

“But”—Moss looked all around the lab—“does it ever bother you? Do you ever consider the cost in terms of the progress we’ve made? We would lose all of this.”

“We’ve already lost it. We can’t contain or control what this is, what it means, what it can do.”

“What it can do. You can imagine how that looks through my eyes.”

Parmenter nodded. “I realize—”

“Do you? I’m dying, and this”—he looked around the room at the amazing Machine—“this could have saved me … and come on, being realistic, of course I have to wonder if there isn’t something we don’t know yet, some tiny, hidden secret yet to be discovered that could change the rules.”

Well,Parmenter thought, it’s happened.“Loren, you do remember all the steps we went through where we talked just as you’re talking now, and how those steps brought us to this pitiful point. Ifwe hadn’t stolen Mandy’s body and reverted it without anyone’s permission or knowledge; ifwe’d not tried a cover-up of Watergate proportions instead of admitting our error; ifwe hadn’t, from the start, chosen the Machine over every human life we entangled with it; ifwe hadn’t reached the point where we were actually plotting to retrace and kill an innocent young woman …”

“But you’re fine with letting your own friend and colleague die.”

Parmenter’s heart sank. “It’s more than your life and Mandy’s. It’s the nature of the Machine coupled with the nature of mankind. We’ve already demonstrated the results in this very lab, in our own choices and actions.”

“I see it differently.”

“I can understand that. I was expecting it, to be honest.”

“Is that why you didn’t trust me with Mandy’s reversion data?”

Well, now we’re getting down to it.“Loren, I would hardly trust myself, and it was an extreme act of trust for Mandy to do so. She trusted me with her life.”

Just then the hallway door opened and several men came into the room. Parmenter recognized Martin DuFresne, Carlson, and three other physicians in DuFresne’s camp– speak of the devil!There were three other men he’d seen maybe once before. They were the government interests who stayed deep in the background, unnamed, unseen, making things happen, definitely not to be trusted. Last through the door were two men he’d not seen before: one was dark, Mediterranean, perhaps Middle Eastern, the other blond, with a ruddy, pockmarked face.

He nodded at the men in greeting. They didn’t nod back or say a word as they assembled in a rough line behind the command console, eyes unfriendly, wary.

Parmenter eyed them all, then Moss. “Don’t tell me. You’ve changed sides.”

Moss gave his hand a little turn upward. “It’s my life, Jerry. If we keep going with the Machine recalibrated and Mandy no longer a factor, we might find a way to make a reversion stick.”

“Yours, I take it.”

Moss jerked his head in the direction of DuFresne and company. “They put me first in line.”

Parmenter knew he had little or nothing with which to bargain. “I could never betray Mandy’s trust. I can’t give you the information.”

Moss only smiled. “We have it.”

Mandy let Seamus walk her to her dressing room—the new one above and behind the big room stage, the one with the rich carpet, mile-long makeup counter, huge, illuminated mirror, full bath with walk-in shower, and separate lounge area where she could relax, do interviews, entertain guests. He seemed particularly pleased to show her her name on the door, just the way she liked it: Mandy Whitacre.

Facing her, his hands on her shoulders, he told her, “This is it, sweetie. But don’t think of this as an arrival; think of it as a beginning. This is where we place the bar and we rise from here.”

“I hope I can do you proud,” she said.

“I have every confidence that you will—”

She cut off his sentence with a kiss, then gave him a look she hoped would show her appreciation. “Gotta get ready.”

He enjoyed the kiss, she could tell. “We’ll all be waiting.” He threw her a little salute and backed down the hall, keeping her in sight until she closed the dressing room door.

Once inside, she rushed into the luxurious, marble-floored bathroom and washed the kiss from her face.

* * *

Parmenter didn’t have to ask; DuFresne seemed nearly bursting to tell him. “Seamus Downey was hired by our friends here, which meant he had all the inroads and connections with the government he could have needed. He got her a new identity so she’d blend into the system unnoticed, be able to work for a living and have as normal a life as possible, and most especially, confide in him when the time came.”

Moss was allowed to finish the revelation. “When she visited the fairgrounds, he was there, taking note of the time, the date, and the exact location. We ran the information through the simulator and with a little finessing we got the numbers to jibe. We can recalibrate.”

Parmenter pushed Moss to say it, maybe think it. “And then?”

“And then we recover full control of the Machine and a space-time fabric free of deflection, a blank slate. From there, we continue to explore, and I promise, we willwork out the problems.”

“You made no mention of what will happen to Mandy.”

Moss only gave his head a dismissive tilt. “It’s a foregone conclusion.”

Parmenter looked at the gathering. “Or what will happen to me.”

DuFresne spoke. “It would be impossible to ignore your immeasurable value to this project. We can only hope that, in time, you’ll be able to put the greater good above these momentary difficulties. I can assure you, you’ll be kept safe and the process will be painless.”

“As a matter of fact,” Moss added, “this is one way your invention can do you a world of good. When you wake up, you’ll be a year younger, and as far as you’ll remember, all this trouble never happened.”

The thought of fleeing had no sooner entered Parmenter’s head than a lightning bolt shot through his body and every motor nerve seemed to short out. He saw the pockmarked face above him and felt the prick of a needle in his neck, but he could do nothing about it.

At 12:54, Mandy sat alone at the oversize makeup counter where she really had to get going on her showbiz face and her showbiz hair, but had to be sure, had to try things first. Cradling her chin in one hand and keeping the other in her lap, she toyed with the lipsticks, makeup brushes, eyeliner, foundation, and blush, making them scoot about the counter like little bumper cars, each one independently controlled. A tube of mascara, an eyebrow pencil, and a lipstick brush did a drag race, popping wheelies at one end of the counter and zipping down the counter until the mascara spun out, the eyebrow pencil sputtered out, and the lipstick brush won, screeching around a tight victory circle and then dancing in victory. The foundation and a lipstick were doing a figure eight and about to collide in the middle; she made the lipstick jump over the foundation and continue on. She closed her eyes and placed herself aboard each little item as it scurried around the counter. This would have been a load of fun any other day.

As the makeup kept moving around the counter, she eyed a chair, reached invisibly, and lifted it, holding it in space. Beyond the chair, the three aspens jutted up through the floor and disappeared through the ceiling; the white paddock fence divided the room.

Sure would like to bethere right now.

“Looks like our magician friend is rehearsing,” said Moss, now in charge at the command console as his cohorts observed with unbroken attention. The monitors were showing small deflections as Mandy multiplied herself and made things move. “She is really good at this! She has twelve separate timelines working right now, each one controlling a different object.”

DuFresne expressed the sentiments of all. “We have got to master this! We need to achieve this level of control.”

“We will—or may I say, Iwill?”

“So what happens when we recalibrate? Will that kill her ability?”

“Now’s when we find out.” Moss entered the vital numbers. “We enter the ending point, 13:05:23, September 12, 1970, and have the Machine reverse-calculate from there back to 10:17:24, September 17, 2010. That should bring the Machine back to its original setting and we can regain control.” He entered some more commands until the cursor blinked on the final field, Initiate. “Hang on to your hats.” He hit the Enter key. The monitors filled with a flurry of numbers and graphic patterns moving faster than the eye could follow.

Clunk! The chair landed on the floor and toppled over. Mandy’s mind went spinning away from the objects on the counter, and she could no longer see herself piloting each one. A lipstick and a makeup brush fell on the floor. The vision of the aspens and the fence dissolved. The room was deathly quiet, and Mandy felt as if she were totally, really there in the room, a solid floor beneath her, solid walls around her, no sense of drifting, no invisible currents and eddies swirling around her.

What happened?

She felt strangely awake, as if she’d been in a trance for the past several months. Was this how normal really felt? She forcefully blinked her eyes and looked about the room, just trying to perceive and understand it. So this is where I am?She could smell the newness of the carpet, the sweet smell of the makeup for the first time; there was no burning smell to cover it.

Is this normal? Maybe it is.

But … I can’t have normal, not today.

She looked in the mirror and saw the same Mandy Whitacre she’d been since the county fair. That hadn’t changed.

But something had.

chapter

50

The bleachers were filling up: a busload of bald and blue-rinsed retirees making a special stop, moms, dads, and restless kids, younger couples without kids, slightly seasoned couples away from their kids, single guys on a lark, single girls eyeing the single guys, older guys with younger women, tourists with all sizes and types of cameras. The crowd was buzzing, eyeing the stage, the whimsical forest, the volcano intermittently grumbling and burping smoke. The TV crews were setting up their cameras along the top of the bleachers, down on the ground, anywhere they could get a good shot, and Emile was advising them what would be happening and where.

Dane blended with the crowd, sitting on the top row of the bleachers but about to surrender his spot as the crowd pressed in. From here everything looked ready to roll, but he was making sure of the last few items on his checklist: cable cinch, tight; escape hatch packing bolt, removed; release hook, functional; stage clock—the oversize hourglass that ran for one minute—operative. The winds were favorable.

One thing still unchecked: the call he would have to get from Parmenter by 1:30 if, and only if, there was no need to go ahead. He checked his watch: 1:10.

In the makeshift sleeping quarters adjacent to the lab, Parmenter lay on the bed unconscious, his phone in his pocket.

In the lab, as Moss and DuFresne watched and the others wondered, streams and columns of numbers counted down and graphs jittered until finally, with an electronic warble, the Machine rebooted and the original control interface filled the screen, the fields clear.

With one victorious clap of his hands Moss announced, “Gentlemen, we are back online. I’ll keep the fields open for her input and let her have control. We want her confident.”

DuFresne spoke to Mr. Stone and Mr. Mortimer. “Let’s get it done.”

They hurried out the door.

He asked Moss, “So what if she tries to go interdimensional to escape?”

Moss wagged his head. “We won’t give her that. The moment she’s in the pod, we retrace.” He puffed a little sigh of relief. “And with her total weight no more than 112, she won’t have anywhere else she can go.”

“Except the volcano,” DuFresne suggested, amused at his own wit.

“What more could we ask for?”

One of the staff set a video monitor atop the console. “Seamus is sending video.”

The monitor lit up and after some snow and flicker the picture appeared. Seamus was shooting from the parking lot, looking up at the bleachers, panning across the stage.

DuFresne donned a headset. “Seamus, can you hear me?”

Seamus, wireless earpiece in place, kept taking in the scene as he replied, “Loud and clear.”

“Excellent,” came DuFresne’s reply. “Be advised, we have control of the room and the Machine is recalibrated. Stone and Mortimer are on their way.”

“Very good,” Seamus replied, giving them a view of the crane. “No problems here. They’re going ahead with it.”

Mandy stood in the middle of the dressing room, eyes closed, a silver, glimmering hula hoop in her hands, feeling the texture and weight, the curve of the circle, smelling the plastic. Her palms were sweating.

All right, now remember… remember!

She set the hoop against a chair, backed away, and tried to reach across space and time. The hoop just sat there, far away, untouchable, unreachable.

She looked at Bonkers, Carson, Maybelle, and Lily, perched peacefully in their cage, nibbling on seeds, preening. She tried to reach … she couldn’t feel them, they didn’t sense her.

What a fine fix to be in: she was normal, in the solid, real world, and hereshe was panicking. Dear God, no! I’ve got to find it, I’ve got to find it—

A gentle knock on the door. It opened.

Keisha, with costumes on hangers. “Hi. Guess it’s time.”

It was 1:20 when Dane stood beside the crane checking the zip line, the illusion’s secret avenue back to the ground. From any angle of view the audience would have, it was obscured by the crane’s boom and allowed the performer to descend to the ground unseen and finish the escape. The thing was a real pain to get right, but Emile managed. Dane’s cell phone hummed on his belt.

“Yeah.”

“Dane”—Mandy sounded troubled—“could you talk to me just a little bit?”

He sighed, and she probably heard it. He wanted to talk with her, touch her, open his heart more than anything else in the world, but would that achieve the effect they needed?

“Are you sure you should—”

“Dane, I just need …” She wastroubled. “I need to see something, just feelsomething.”

Oh, no. Not this late in the game.“Are you all right? Are you—”

“Tell me how we met.”

He checked his watch. “Uh … you mean, at the fair?”

“Yes, tell me.”

It would be all right to tell her, even the best thing he could do. He brought back the memory—not at all difficult, it was one of his favorites. “It was in the middle of Marvellini’s dove routine. I was in the wings setting up the levitating table when I saw you in the front row—just you. Joanie and Angie were there, but the sunlight was on you, you were the one glowing. Your hair was like, well, like a sun-washed wheat field in summer, and the wonder in your eyes … I couldn’t look away.”

Keisha sat waiting, entirely patient.

Mandy sat on the edge of her chair, dabbing tears from her eyes, drinking in the sound of Dane’s voice and every detail she wished she could remember.

“You loved those doves,” he told her. “I could tell. You watched them more than Marvellini, and then … that dove—his name was Snickers—he must have picked up on that because he chose you over Marvellini. He came flying out of Marvellini’s sleeve and headed straight for you. He landed on your finger like you already knew each other and he was really happy there. I think he would have stayed.”

Dane could still feel what he felt that day, and it came through his voice. “It was my job to patch up the gaffes, so I ran down to get Snickers back, but when you stood up with that dove on your hand, and his little head right next to your cheek … I wished I had a camera, but that’s okay, I can still see it, that image of you, just so perfect I had to get you up on that stage and …” A flood of emotion overtook him too quickly to disguise it, but maybe that was just as well. “When you danced across the stage and took a bow, I felt my future was determined from that moment. I felt, I knew, you were the one.”

She’d have to do her makeup over again. But from somewhere, some part of her could feel him, even hear his voice without the phone. She looked across the room at the hula hoop and reached. It stood up, rolled back and forth, did a spin in place.

“Thank you, Mr. Collins.” A quick, tear-blurred glance at ever-patient Keisha. “I gotta go.”

Dane clicked off his phone and slipped it back on his belt. He cleared his eyes just as three people appeared on the stage: Seamus Downey and …

Dane edged behind the crane, out of sight. Remarkable. Shocking, actually. The other two were dressed in uniforms to make them look as if they were from the fire department. One carried a clipboard, and they seemed to be giving the stage an additional, last-minute once-over. The olive-skinned guy he was seeing for the first time, but the blond guy … he was wearing sunglasses and a fireman’s dress hat, supposedly to hide his appearance, but his war-torn face Dane remembered vividly—he’d almost had a knock-down, drag-out fight with him back in his pasture in Idaho, and come to think of it, Mandy actually had.

Dane could see Emile in his control booth on the third level of the parking garage behind the bleachers. Dane got on his radio. “Emile, this is Dane.”

“Emile. Go ahead.”

“Who are those guys on the stage?”

“Fire inspectors.”

“We’ve already passed inspection.”

“Seamus called for it. He wanted to be sure.”

“Oh, he did, did he?”

“I just got off the phone with the fire department. They didn’t send them.”

“I’ll get right back to you.”

So Seamus Downey, who miraculously produced a fifty-thousand-dollar settlement from the Spokane County Medical Center for hiring those two guys, was now in their company as they snooped around the effects. Bernadette Nolan was right: the hospital in Spokane never hired them.

But DuFresne and his government backers did, along with Seamus Downey, Mandy’s bighearted manager who made it a point to find out exactly where and when Mandy’s reversion placed her.

The three men were spending a noticeable amount of time checking out the pod.

Dane checked his watch. It was 1:30, and there had been no call from Parmenter. They all agreed that Parmenter would have to remain at his post for the plan to work, and the scientist said he had a contingency plan, but now Dane had to abide by Parmenter’s final admonition, “If I don’t call by 1:30, if you don’t hear from me …”

He got on the radio again. “This is Dane. We have a go. Please acknowledge.”

“This is Emile. We have a go.”

“This is Preston. We have a go.”

Atop the semi, Preston and three crewmen unfastened the Velcro loops from around the bundle of webbing and carefully lifted the top edge of what looked like a huge fishnet woven from fine, nearly invisible fibers.

In the lab, Moss and DuFresne received a quick message in their headsets from Mr. Stone. “All set.”

By 1:30 Mandy had slipped on the white, angelic costume and then, with Keisha’s help, folded and secured its flowing edges inside a black leather bodysuit.

Keisha closed up the last breakaway seam of the bodysuit and asked, “All right, how’s that?”

Mandy did some stretches, went through a few dance moves, waved her arms about. “It’s working.”

“Looks good from here.” Then she lowered her voice as if sharing a secret. “I allowed for a few extra pounds.” She winked.

Mandy slipped a silvery tunic over the bodysuit and looked in the mirror, seeing once again Keisha’s signature touch.

“Just like old times,” Keisha said. “You look as marvelous as ever you did.”

Mandy turned to face her. This was good-bye. “I wish I could have remembered you.”

Keisha placed a hand on each side of her face. “I do earnestly hope to see you again.”

At 1:40, Dane, Mandy, Emile, Max, Andy, and Carl met under the stage for a word of prayer. Mandy figured it was a prayer meeting one would only see in show business: she dressed in silver and black like a fantasy hero; Dane and Emile looking tense, still wearing radio headsets; enormous Max dressed like an executioner, Mandy’s shackles draped around his neck; Andy and Carl dressed like slithery henchmen from the dark side, Carl carrying Mandy’s handcuffs. Dane and Mandy were the only Christian believers. Emile was agnostic, Andy was into Scientology, Max was searching and thinking his family ought to find a church somewhere, Carl didn’t give religion much thought at all.

But they all prayed together because they were a team, and she could feel it: this was her moment, they’d all worked very hard to make it happen, and their hearts were with her.

Dane said the Amen and then let them know, “Gentlemen, it’s been a privilege.”

“Right on,” “Same here,” “Back at you,” “Let’s do it again sometime” … they dismissed to their stations.

“And lady,” Dane said.

She gazed into eyes she needed time, precious time, to fully understand. A moment, an eternity, passed, and there were no words. He finally looked to make sure they were alone and said quietly, “It’s a go. God be with you.” He turned his eyes away and without another word, walked out, leaving her alone in the semidark amid the panels and rigging and girders, alone to take hold, finish the show, and find her way back.