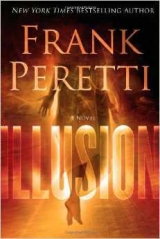

Текст книги "Illusion"

Автор книги: Фрэнк Перетти

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

He went for it. “And I’ll bet you raised doves.”

All right, now, that was just plain creepy. Was it happening again? Her insides hurt the way they used to when her folks would catch her doing something wrong; her fingers were quivering as she groped for her lunch sack and peered inside. “Did you … ? What did you say?”

He was studying her. She felt very looked at. “I said, ‘I’ll bet you raised doves.’”

“Is, is this a magician thing you’re doing?”

“A magician thing?”

She pulled out her apple and cheese slices and didn’t take her eyes off them. “You know, uh, mentalism? Reading my mind? You’re really good. You’ve got me shaking.” She took a big bite. It was easier than talking.

It was time to back off. “Oh, oh, no, no. It’s just luck, just probability. You grew up on a ranch, I just started guessing the animals on it. And the doves”—she never really answered that one, did she?—“well, doves are a staple for most magicians, you were a magician in your youth, on a ranch, so I thought you may have had some doves. I think we’ll be working with doves at some point, so I asked.”

She looked relieved but kept on chewing.

“So … you had doves?”

She looked as if she hated to admit it, but finally she nodded, one cheek still full.

Well, that was enough load for either of them to bear for now and still maintain the agenda that brought them together—oh, yes, there wasthat, wasn’t there? He took a bite from his sandwich and gave them both a break to depressurize. She took several more bites; apparently she was going to extend the silence as long as she could.

Now he cleared his throat. “Anyway, getting around to my little opening sermon …” She was chewing and receptive. The pressure was off for now—soon to return, he feared. “I’ve seen you perform at McCaffee’s twice, and there was that time on the street …”

She winced a little and said, “Right.”

“So I’ve seen you as a Gypsy, I’ve seen you as a Hobett, I’ve seen you as … well, let’s call her the Enigmatic Damsel in Distress … and I’ve seen you as a Secretive Attorney’s Client hiding behind, oh, let’s call it the Downey Doctrine: ‘Teach me and coach me and help me to be somebody but don’t ask me who I am.’ But that issue right there is the one I keep coming back to. Through all of this, I find myself constantly having to face the same fundamental question: who are you?”

She’d run out of apple slices so she had no excuse for her silence. Even so, not a speakableword came to her. She thought, I’d love to know, but dared not tell him. She could only stare at him, tilt her head, and stare some more. One of her minds, one of her brains, one of her selves might know, but by now they were all so mixed up, like scrambled eggs.

And maybe that was his point.

Oh, thank the Lord, he’s going to keep talking.“You have to be sure about that for two big reasons. Number one: because knowing who you are, and liking who you are, are going to read right through to your audience. If you’re hiding from them, they may not be able to pin down what it is they feel about you, but they won’t be able to connect, and if that’s the case, you’ll never rise above that sea of magicians out there who all bought the same trunkful of tricks from the same catalog. Maybe you’ve noticed how a great trick in a bad magician’s hands can be a same old thing, klutzy and boring, while a mundane trick in a great magician’s hands can be a thoroughly entertaining experience. That should tell you something: the magic is in the magician.”

He stopped and looked away, and the silence was awkward. He looked to her again, tried to speak but had to look down, stroking his face. “Anyway …” She got teary-eyed watching him. He drew a deep breath and tried again. “Anyway … getting to my point … you’re a natural. You can connect and charm and enchant better than some of the best performers out there. But I still get the sense you’re working a little too hard to get through and it’s because you’re hiding. All the characters you’ve tried—the Gypsy, the Hobett, the Client—they’re not you. I know that sounds pretty obvious, but any performer who knows herself and isn’t afraid to show it can wear any outfit and be any character and still come through. I’m sensing that you’re afraid to do that, that these other faces are there so you don’t have to be. If we can, I’d like to see if you can drop that barrier and touch your audience directly. You have the nature within you, the wonder, the joy of the experience. We need to turn those things loose so they flow right through without a bulletproof shield in the way. Am I making sense here?”

Now, shewas trying not to cry. He’d not only described her work; he’d also described her life. Her fingers went over her mouth, an unconscious gesture, as if she could bar her real self from bursting out and saying … well, such things simply could not be said.

Dane had been piecing together this little speech for quite some time, gathering it like fallen apples from every moment he’d spent with her up until now. He knew it was right for her as a performer, which justified delivering it. That it was right for her as a person he hadn’t wanted to address, but now her silent gaze, her glistening eyes told him he’d addressed it anyway. His own emotional investment aside, maybe it was still for the best.

He pushed ahead. “The second reason you need to know who you are is the nature of this business. Mark my words: if you ever achieve the level of success I think you’re capable of, you’re going to find yourself in a world that wants to repackage you and make you something you aren’t; they have to sell you, so they’ll put a face and a name on you that will be bigger and more glamorous than you really are. They’ll dress you up, stand you up, light you up, and print you up with the specific aim of squeezing every last possible dime out of you, and if you do not know who you are, you’ll make the same fatal mistake so many others have made: you’ll believe them.You’ll buy what they’re selling, thinking it’s you, and oh, the euphoria, the cloud-nine high you feel!

“But it’s all a lie, and lies don’t last. When the commodity they have made you has outlasted its marketability—when the stores start returning all the T-shirts and school folders and posters and lunch boxes and coloring books that have your face on them—when nobody wants to buy ‘Eloise Kramer’ anymore, they’ll pitch her into the nearest Dumpster, they’ll recycle all the paper and cardboard, and they’ll make room for the next big star, and then who will yoube?

“Ask those who have gone before you, the ones who thought the business, the crowds, the applause defined them. It’s no picnic betting your soul on a personality, an image that is other than you, because when you lose the bet, you end up sitting alone in your room and there’s nobody there.”

She was wiping her eyes with her napkin. He could plainly see he’d stirred up all kinds of little ghosts inside her. Once again, it was time to back off.

“It’s okay,” he said. “Now, I do remember what you said about thinking you’re somebody else, and I wonder if, at least as long as you’re around here, you might not trouble yourself about that? You are somebody. Just be that. That’s how I’m going to play it. During all your training, I’m going to assume that you are not the Gypsy or the Hobett or the Attorney’s Client, or any other face that comes along, but yourself, however you may emerge over the days and weeks. And if you need permission, if you need someone to tell you it’s okay to be who you are, I’ll do that for you. Can you look at me, please?”

Her blue eyes returned from a moment of reflection and he saw in them a longing she’d never shared before, a hunger so deep it seemed a life’s store of wisdom and answers might never satisfy it. “When you are here on this ranch, when you are working, when you are learning from me, you may be yourself. It’s all right. It’s perfectly safe. Do you understand?”

She broke into sobs, her voice quaking. “I don’t know who she is.”

Pay dirt. He got a little excited and pointed. “That. That right there, whoever’s crying right now, whoever’s feeling, whoever just said that, that’s you. Let’s work with her.”

chapter

25

Daddy used to say one of the big rewards in life was looking back at a job well done, and you had to have done it to know. Cleaning out a stall in a barn was not glamorous, definitely not cushy, but in Eloise’s frame of mind on a snowy Tuesday morning, the work had a good old feeling to it, stirring something deep inside that left her better than she would have been.

Being solitary was part of it, by herself in a place by itself, raking, lifting, and pitching, her thoughts free to relay through her mind and no sound in that barn-tainted air but the rustle of the straw and the soft chime of the pitchfork tines.

The memories were part of it, memories this place brought back from not so long ago. They were Mandy’s, but Eloise had permission, so she let them return and drank them in: the quiet nicker of the horses, the steam on their breath, and the thumping of their hooves; the continuous, brown-eyed stare of the llamas; the cooing and head bobbing of the doves; the smell of tractor exhaust and diesel and the black smear of grease on her gloves.

Permission, yes, permission was part of it. Wow.Never mind whether Mr. Collins had the power or right to change the rules, he just did it, and ever since yesterday’s session warm little fires began to glow inside her, thawing things out, waking things up. What had she thought that night when he first came to see her perform, that he was some kind of window to somewhere she’d been? Though she hadn’t a clue whatever gave her such a notion, her first day under his tutelage made her all the more a believer.

Mr. Collins started with conventional stuff right there in the breakfast nook, going through palmings, flourishes, loads, and steals, just talking, teasing, loosening up over coffee until he had an idea what she could do and she had time to get comfortable. He never said that was his plan, but it probably was, and it worked. After an hour of gentle guidance and good laughs, she was sure he wouldn’t bite her and she wouldn’t have to die of embarrassment.

When she was ready, they moved into the makeshift restaurant in his dining room, three tables with tablecloths and dishes set out as if someone were sitting there eating or having coffee. He took a seat at one table and became her audience.

Before she could start she had to know—and she was afraid to ask, “Do I … do we need to talk about how I do the tricks?”

To her surprise, he didn’t care to know. Apart from proper technical execution, he said, the “how” didn’t matter. What mattered was the “magic,” what her audience experienced. If all they brought away from her performance were question marks, she’d shortchanged them. It was never to be a case of “I can do something you can’t” but rather “I’m glad to be with you so we can have a grand time together.”

“It’s not about you or your ego, it’s about them,” he told her. “To categorize it, you’re after three things: rapt attention, laughter, and astonishment, and all three of these have one big thing in common: they’re human. They’re about unique moments and feelings. They create memories, and that’s what good showmanship is all about.”

And that was his guiding principle as she did her show and he commented.

“I love the wonder in your eyes,” he said. “Never lose that. You might do the same trick a thousand times, but if you never lose the wonder, you’ll always pull them into the experience and they’ll feel it with you.”

“Oops, watch your body position; you just lost this table over here. There! Play in that arc right there! Now we can all see you.”

She faltered the first few minutes, but he cured that by giving her attention, laughter, and astonishment, as if he’d never seen her act before. Maybe he was role-playing for teaching purposes, but she bought it and drank in everything he told her.

“Hold the cards up about chest height so I can see them over all these heads in front of me. That’s beautiful. See? Now I can enjoy your facial expressions at the same time.”

“Give those silver dollars names, at least in your mind. That’s what makes Burt so effective—he’s a living thing, like a pet, like a goofy sidekick. When he has a name and a mind, people feel for him so they love to see him win—which is a mark of your genius, by the way. So complete the story: the dollars are mischievous so they get lost, but then they still love you so they come back. Keep it subtle, but humanize them; give them feelings.”

They worked so carefully and talked about so many things it took them close to three hours to work through the first ten minutes of her act.

But what a finish! “Eloise, you can do this. You have the instinct for it, the magic inside you. You’ve made me real proud.”

You’ve made me real proud.Words from Daddy, Mandy’s fondest memory, and hers today. She finished the last stall on that side of the barn, then skipped and pranced to the other side, throwing in a stag leap that wasn’t very good but was okay, she was wearing work clothes and dancing on straw. She sang music for the move “Raindrops keep fallin’ on my head …” But not so much that her eyes would get red because crying wasn’t for her today, and she had no complaints. She had belief in herself and memories she didn’t have to worry about.

She started the first stall, raking and pitching, raking and pitching, and it must have been her mood, because songs kept coming to her. “Do, do, do, lookin’ out my back door!”

Nearly finished with stall one. “She’s just a hawwwwwng keetonk woman!” Daddy would have frowned on that one, so she found another, “I’ll Be There,” by the Jackson 5—come to think of it, little Michael may have become a solo act; she’d heard his name mentioned here and there.

And whatever happened to Elvis? Boy, he’d be really old by now. “Well, since ma babay lef’ me! I foun’ a noo plaze to dwell …” The pitchfork made a great mike stand and she still knew the moves.

Oops. She wasn’t getting work done. Back to it.

Ed Sullivan. She could do a great impression of him—she didn’t bother moving like him because he hardly moved at all and she’d get no work done. “Right heeyer, on our really big shoo! The Bee-uls! Less hear it, less hear it!”

Flip Wilson. “The devil made me buy this dress! I said, ‘Devil, cut it owwwt!’”

Dean Martin. “Everybody … loves somebody … sometime… .”

Laugh-In.“Sock it to me, sock it to me, sock it to me!”

Scrape. Swish. Clunk.

Right when she was having fun. She stopped to listen, stifling her breath. Somebody was in the next stall, raking and pitching straw, same as yesterday.

Come on, now, I didn’t ask for this. I was having a good time here.

But now the sound stopped.

Her heart was racing. She didn’t want to know, but then again she did. She went to the stall door and peered out into the barn.

There was a pile of straw outside the next stall that hadn’t been there before, and now she heard a quiet, almost sneaky kind of padding in the straw next door.

“Hello?”

Just like yesterday, no one answered.

“Is anybody there? Please?”

No answer.

“Pretty please, with peanut butter on top?”

Okay. Time to look.

She held her pitchfork in front of her, tines raised as if she’d ever impale anybody, hands clasping the handle tightly but trembling anyway. The fact that she was scared made her angry, which gave her the gumption to step out of her own stall and look in the other. “Just talk to me.” Her voice was high and quivery. “I won’t hurt you. And if you’re not there, then you don’t have to say anything because you’re not there and it’s all my problem, okay?”

Somebody’d been working in the stall. Half of it was cleaned out, the straw and debris in a heap just outside the stall door. She stopped short of going in. Somebody could be waiting just around the corner of the doorway and jump her if she stuck a toe in there. Better to stay outside and listen, just listen and see if anything moved. She kept the pitchfork straight out in front of her, standing motionless until she felt silly. At last she decided, Well, okay, I looked. If I stop here I won’t hurt anybody, including me, and that’s the big deal in all this, not to hurt myself or anybody else. After that, I just need to not act weird.

And standing out here pointing a pitchfork at an empty stall was weird. What if Shirley came in?

She calmed herself, put on Normal, and went back to her own stall to finish it up. “Let’s go surfin’ now, everybody’s learnin’ how, come on a safari with meeee!” The songs didn’t come quite as easily this time, but they came.

When she’d finished the first stall, she took a peek toward the second.

The heap of straw that used to be in front of the stall’s door wasn’t there anymore. The stall wasn’t cleaned out either, not half of it, not any of it.

Hoo, boy. Second verse, same as the first.

Live with it. Roll with it. Get to work.If this was as bad as it got …

But she’d seen it worse than this, and that was what scared her. That whole levitation thing the other night she probably brought on herself, but some of the other stuff, including this, she never asked for, it just came along and happened to her, and what was she supposed to do, act like it didn’t?

Just don’t hurt anybody. Don’t hurt anybody and they won’t lock you up.

She got to work, unable, unwilling to sing anymore. She just pitched the hay out the door …

“The devil made me buy this dress! I said, ‘Devil, cut it owwwt!’” It was a voice that sounded just like her trying to sound like Flip Wilson.

“Everybody … loves somebody … sometime… .” It was coming from the first stall, her voice being silly and singing like Dean Martin.

“Sock it to me, sock it to me, sock it to me!” She’d heard recordings of her voice, but this was downright, flat-out real. Or wasn’t it? Was it live, or was it Memorex?

Eloise yanked in her pitchfork and it scraped on the ground. The hay swished aside. She flipped the tines upward and the other end hit the ground with a clunk.

The girl in the last stall went silent and still. She was listening, Eloise could just feel it. The straw crunched and squeaked ever so quietly under the girl’s feet as she went to her stall door.

What in the heck am I gonna do? Who is that over there really?

“Hello?” came the voice. It was her. She. Herself.

Get out of sight, that’s what you do, because if you see yourself standing in this stall you’re gonna freak out and you might get stabbed by yourself with a pitchfork and that would be way too freaky, that would be the ultimate implosion of your brain into itself and what are you going to tell Shirley when you’ve stabbed yourself with your own pitchfork, I did it but it wasn’t me?Eloise padded carefully, as silently as she could, to the corner of the stall adjacent to the door, the only place she could hide from anyone looking in. “Hello?”

Oh, God help me, she’s going to come over here, isn’t she?

“Is anybody there? Please?”

What if I did answer?

“Pretty please, with peanut butter on top?”

Here she came. Eloise could hear her stepping through the straw. “Just talk to me.” Her voice was high and quivery. “I won’t hurt you. And if you’re not there, then you don’t have to say anything because you’re not there and it’s all my problem, okay?”

She stopped outside the stall, and Eloise remembered—how totally nuts was this?—that when she was the girl out there she was too afraid to come in and look. Okay, so don’t look. I don’t want to see you either.

She didn’t come in, but she stood there and stood there forever. Get back to work, uh, me.

Finally! The girl who sounded just like her gave it up and headed back to her own stall.

Eloise had to look. She didn’t want to, but she had to. She tiptoed to the stall door, leaned, and stuck one eye and her nose outside.

It was her. She. Herself, in the same clothes with the same pitchfork just slipping out of sight into the other stall. Vivid. Real. Eloise could have touched her.

Would her other self have felt it?

Her other self started singing again, her voice weak and looking for a key, “Let’s go surfin’ now, everybody’s learnin’ how, come on a safari with meeee!”

And then the singing stopped and there was a heap of straw and manure outside that stall and no movement inside. Eloise stepped over and looked, finding what she expected: the stall cleaned out, just the way she left it, and no one there.

Her encounter with herself made it all the more awkward—close to miserable, actually—when Mr. Collins suggested doing the card box routine with Shirley as the volunteer. “You need a live, self-aware, emotional person to work with on this one.”

But Shirley? Her supervisor? Maybe Mr. Collins wanted Eloise to work under stress by working with a fussy volunteer. Wonderful. All Eloise had to do was keep her brain in this universe while poking around in another to do the trick—without having another Eloise show up—and put on a great performance with both Shirley and Mr. Collins watching her every move.

Well, as Daddy would have told her, she could either get back into her hospital scrubs or take this dadgum bull by the horns and wrestle it down.

Shirley came in right after lunch, took off her winter coat, hat, boots, and gloves, and sat at the third table in Mr. Collins’s restaurant. Eloise launched into the routine, putting the deck of cards in Shirley’s hand while Shirley just sat there playing along because her boss asked her to.

What was that Scripture about a prophet being without honor in his own country?

Well, those winning moments do eventually come around. When the cards stood up one after the other and formed a box at Eloise’s finger-wiggling command, Shirley’s stoic face finally broke into a smile, as if she were holding a baby chick.

When Eloise produced the key to the tractor from the box, she had Shirley right in the astonishment zone. “That was clever!”

“Excellent,” said Mr. Collins. “I like you working from both sides, that breaks it up visually, but let’s motivate the moves a little more. Can you manipulate the cards with your other hand as well?”

Eloise could, and did, and Shirley sat there just being the center of focus for Eloise to move around.

“And let’s try a different gesture each time you make one stand up so you aren’t repeating yourself.”

Oh, right.Eloise hadn’t thought of that—among many other things.

“Okay, now, slow down. When each card stands up, give that moment your emotional attention, and your audience will follow you. They need to feel what you’re doing, not just see it.”

Emotional attention?Well, she found it with God’s help and worked it in.

When Shirley got back into her winter coat, hat, boots, and gloves, she cocked her eyebrows at Eloise, nodded to herself, and said, “Huh!”

And then she left.

“That should help,” Dane said.

His student looked relieved. “I’m not sure she likes me.”

“Shirley’s a good gal. I think she’s just looking out for me.”

“Well, she likes how I clean up the stalls.”

“She likes your magic, too, and so do I. Just give her time. So … oh, right! Before we wrap up I wanted to talk about your levitation.”

“Oh, I can’t do that here.” Instant reaction, as if he’d proposed doing a root canal.

“Oh, well, sure, I figured as much. That’s incredible rigging. It’s got me stumped, so give yourself a pat on the back for that.”

“As a matter of fact … I don’t think I ever want to do it again.”

She really was afraid, as if he’d cornered her. “Hey, it’s all right. It’s your illusion, your show. Did you need any kind of help with it?”

She shook her head and he could see a barrier going up. “No.”

“Okay. End of subject. No problem. You look tired.”

It was nearly the same “tired” she displayed after she did the levitation the other night. “I am.”

“And stressed.”

She managed to laugh some of it away. “I am.”

“Well, the stress was planned, as you may have gathered. But you did well, so let’s call it a day. Go home, flop on the couch, and be happy with yourself.”

She managed a weak smile as she reached for her coat. “Thank you.”

“Nice earrings, by the way.”

That brought a better smile, close to her classic, as her hand went unconsciously to her ear. “Why, thank you!”

Hmm.Had she ever worn those before? He couldn’t recall.