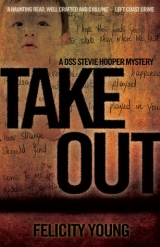

Текст книги "Take Out"

Автор книги: Felicity Young

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

CHAPTER FOUR

Lilly Hardegan turned off her TV and leaned back in the chair with the lacy armrests, pausing for a moment to listen to the drumming of the rain on the orange tiles of her roof. Through her open window the metallic smell of fresh rain on bitumen gusted in. Forcing herself to try to relax and enjoy the scent, she attempted to block out today’s disturbing events, closed her eyes and began to compose the letter she would never write to a person who would never be able to read it.

When she was writing in her head, she saw the words as clearly as if they were printed on a blackboard. But when she tried to say them aloud, it was as if the board had become coated with butter, and the words slid from it and flew around the room and all she had to catch them with was a large-holed net.

She began to compose, leaning back in her chair, fingers of each hand touching, here’s the church here’s the steeple, like the childhood game.

My Dear ... she began, setting the letter out in her head as if it were on a page. I trust this finds you...

A noise from the front of the house disturbed the flow of words. Surely the police wouldn’t be calling on her again when they knew she had so little to tell? She dimmed the table lamp and prised open the venetians. The Pavels’ house was lit like the Gloucester Park trots. The police were still there: she could see silhouettes in the cars, sheltering from the rain, and an officer standing on the front porch, but it had been a while since she’d seen anyone in the street.

Her body tensed. She continued to strain for alien sounds, one hand creeping down the gap between the side of her chair and the wall under the window. The carved texture of the samurai sword’s handle was a comfort, despite the weakness of her grip upon it.

When no more strange sounds seemed forthcoming, she let go of the sword and sank back into her chair. Sometimes she relished the idea of a fight, a chance to get even, with whom or what she still did not rightly know.

There had to be someone, there always was.

My Dear, I hope this finds you in a better state than when we last met

There it was again, a distinct thump, the sound of the front door closing. The passageway light clicked and shone under the door of her room—her sight and hearing were as acute as they’d ever been. The floorboards creaked more softly than usual, as if the person was treading on the tips of his toes, a sneaking teenager home well after curfew. Only two people had keys to the front door, and Skye said she was going home after her last visit. It could only be him.

Oh God, him.

Perhaps if she pretended to be asleep he would go away.

I very much regret everything that has happened and the part I have played in your misery

No, too syrupy, too sentimental. Not like you at all, Lilly, you can’t write that nonsense. Too much too soon; get back to that part later.

The door of the room announced his entrance with a slow moan. She ceased her composing as if, like an EEG, he might sense the activity in her brain. She kept very still in her chair, her eyes closed, keeping her breathing firm and even. His footsteps were softer than usual, as if he were trying to keep silent. A silent little mouse creeping across the lino, scritch scritchity scritch.

A shadow flickered through the red of her closed eyes. She willed her lids to remain steady and not betray her with vibrations. Her ears strained for the sound of his movement. The shadow stilled; he was very close now.

A feeling of dark warmth descended upon her from above.

‘Bloody Japs Bloody Japs!’ the parrot squawked.

Her heart gave an extra thud, her eyes shot open and she sat bolt upright in her chair. ‘You, boy—shock!’

He leapt back as if he’d been stung, clutching a green velvet cushion to his chest. ‘Christ, Moth, I thought you were asleep. I was just fixing your cushion, wanted to make you more comfortable.’

‘Doesn’t need fixing. Fine.’ In hospital she’d overheard the nurses joke about giving a troublesome patient the ‘Tontine treatment’. It didn’t seem funny now.

‘Well you shouldn’t leave it on the floor, it’ll get dirty,’ he said, frisbeeing the cushion onto the bed. He turned to the parrot. ‘And as for you, it’s about bloody time you fell off the perch.’ He tossed a blanket over the cage and made it rock. The parrot let out a final curse and fell silent.

Too vain for glasses, Ralph peered closely at her face. ‘God, Moth, you’re as white as a sheet, are you alright?’

‘Of course we’re alright, just a shock, you shouldn’t call at this time of night, tired, worried, must go to bed...’

‘It’s not late; it’s not even six o’clock. I’m here because the police called me. They said you were upset, said the Pavels have gone missing—does that mean the cops finally got round to checking up on them? I rang them several times you know, like you asked, but I think they thought I was some kind of crank. So what’s happened—no sign of the Pavels at all?’

She shook her head; it was so much easier.

‘I’ll make you a cup of tea.’

She didn’t want a cup of tea; she wanted to go to bed.

‘So ... what exactly did you tell the police?’ he asked as he bustled about the kitchenette. People often remarked upon her son’s resemblance to Sir Richard Branson—tousled grey hair and neatly trimmed goatee beard—and it was an image he seemed determined to cultivate, even adopting a similar dress style to the multi-billionaire. There weren’t many engagements grand enough to get him out of those bright figure-hugging shirts and designer jeans and into a suit. He probably wouldn’t even wear a suit to his mother’s funeral, she thought without sentiment. His ersatz Branson image had won and lost him three wives quicker than the real Branson could polish one of his jets.

He told everyone he was a businessman, but to Lilly Hardegan, her son Ralph would never be anything more than a trumped-up greengrocer.

He put her tea on the table next to her sewing and settled himself on the footstool at her feet. He often complained about the stool, said she should have another chair for visitors, said he hated sitting at her feet like a child. It kept him in his place, Lilly liked to think.

‘Listen, Moth,’ he said as he took one of her hands.

She used to have such pretty hands, she reflected without self-pity. These days they looked more like something found under the lino—too much sun maybe?

‘It’s really important that you tell me exactly what you said to the police,’ Ralph went on. ‘It would be awful if they were given the wrong impression of the Pavels, or of me for that matter, wouldn’t it?’

‘Your friends.’

‘Well, not exactly, Jon Pavel is a business associate really. It’s not necessary to mention my connection with him at all. You see, if you mention me...’ He paused, his eyes becoming sharp slits, nothing like Branson’s at all. ‘You’ll be dropping yourself in it too.’

I was stupid. A stupid, naïve, ignorant old woman. Lilly’s head began to pound. She felt as if she might be having another stroke. Maybe it would be easier for everyone if she did.

His clammy hand gripped hers once more. He was worried now, really worried, but only for himself. No, erase that. He wasn’t merely worried; he was bloody terrified; she could smell the fear in his sweat.

‘I might have to go away for a while, Moth, just to be safe, just until this business with the Pavels calms down. I won’t tell you where I’m going; I think it’s best you don’t know in case they come here looking for me.’

Who did he mean ‘they’—the police? Or was he talking about those awful people he’d got himself mixed up with?

‘Don’t worry, they won’t want you, they know you can’t tell anyone about anything. In the meantime, I’m getting things in motion to get power of attorney. It’s a pain I didn’t organise it before your stroke. Things are tricky now, but I should be able to get it sorted—it’s the only way, you can see that, can’t you?’

No, Lilly couldn’t see it at all. Skye had said she was making a splendid recovery. Her right leg had improved to the extent that she didn’t need a stick any more, and her hand was now good enough to let her tackle a basic cross-stitch. Skye said her speech was sure to follow, and when that happened, she would be taught to read and write again. No, he didn’t need power of attorney. She drummed her feet ineffectually upon the lino. He didn’t, he didn’t, he didn’t! (Image 4.1)

Image 4.1

CHAPTER FIVE

Stevie tried the other window in the room, but like the one overlooking Mrs Hardegan’s place, it was locked and she couldn’t find the key. ‘What a bloody idiot,’ she cursed aloud, kicking at the heavy door. Lucky she didn’t get claustrophobia; lucky, too, the smells from downstairs couldn’t reach her in this hermetically sealed room. On the other hand, could any air get in at all? She panicked for a moment, not daring to breathe. Then she spotted the two air-conditioning vents in the ceiling. The aircon was switched off, but at least it meant that a certain amount of air could get through from the roof space. She let out her pent up breath, whew.

Stay calm, she muttered to herself, pacing the room. You’ve got your mobile with you and you must use it. You don’t get claustrophobia. Someone will get you out, and when that happens you’ll just have to come clean and face the consequences.

But maybe, just maybe, she could find a way around this.

She reached into her overalls for her mobile, relieved to see she had plenty of battery power left. Her first call was to Monty.

‘I’m going to be late home,’ she told him. ‘Skye called with a problem. I need to stick around a bit longer and sort something out for her.’

‘Fine, no worries—where are you?’

‘I’ll explain later. There’s something I need to know, though.’

‘Shoot.’

‘Do you remember a guy called William Trotman? A general duties officer when you were with Joondalup Detectives.’

‘Blinky Bill? What’s he got to do with Skye?’

‘For now I just need his mobile number.’

‘Hang on I’ll check my phone.’

He seemed to be gone an age. When he finally returned he told her he no longer had Trotman’s number in his phone. She started to swear.

‘But I did find it on the old Cardex in the study.’ She tried to ignore the infuriating smile in his voice, remaining calm as he read out the number, returned his ‘love you’ and hung up.

A police car pulled away from the curb. Stevie prayed Trotman was in the remaining one, that he still had the same mobile number.

He answered on the second ring. ‘William Trotman.’

‘It’s Stevie Hooper, Bill. Don’t say a word. Just get out of the car and get away from the others. I need a private chat.’

The car door opened and she saw Trotman’s gangly form unfold into the street. ‘It’s fucking raining, Stevie.’

‘I’m trapped in the upstairs room. Come and get me out without telling anyone.’

Trotman let out a whooping laugh.

‘Just do it, you bastard!’

The door opened easily from the outside. To stop Trotman from asking what she was doing in the upstairs bedroom, she quickly pointed out the missing doorhandle, asking if it had been noted.

‘No idea,’ he said as they thumped down the stairs. ‘That’s the first I heard about it.’ They paused on the front porch, waiting for a break in the rain. A van pulled up alongside the police car. Stevie recognised the high-heeled form of the woman from the deli, hauling herself out with a box of snacks for the troops. Stevie’s stomach gave a hungry moan. It seemed hours since she’d eaten that salad sandwich.

‘But the room was like a prison,’ Stevie said. ‘I still think you should point it out to Fowler, just in case. Get yourself some brownie points.’ God knows he must need them. Fifty-five if he was a day and still a constable first class.

‘It’s probably just something to do with the redecorating that’s been going on,’ Trotman said, as if she should know what he was talking about.

‘Redecorating? What do you mean?’

Trotman took off his glasses and wiped them thoughtfully on his uniform jacket, making them streakier than they already were. ‘The neighbours told one of the lads about a fire here last year. Apparently an electrical fault damaged quite a bit of the inside of the house and they’ve been slowly getting the place reorganised. I guess they were just waiting on some more doorhandles.’

That would account for the fresh paint and lack of personal effects around the house; possibly, too, the boxed items in the storeroom. But what of the dirt, Stevie thought, the neglect of a beautiful house by a family who could easily afford to pay someone to clean it? And more importantly, how could the state of the baby be explained? A figure ran through the rain towards the porch before she could continue with the thought.

Her heart sank. Luke Fowler.

It seemed that during her absence her kitchen had been transformed into a Chinese laundry. Stevie blinked as she looked around the place, at the sheets of pasta draped over every available surface, from the oven doorhandle to the chair backs, the kitchen shelving to the wooden clotheshorse. Limp doughy strips even hung from Monty’s tropical fish tank. ‘See, curtains for the fish!’ Izzy proclaimed.

Stevie finally found the words. ‘I don’t believe this...’

Monty, with flour on the end of his nose and a generous dusting through his rust-coloured hair, put out two placating hands. ‘Don’t say anything, not one more thing. When you said you’d be home late we decided to cook dinner ourselves. It’ll be the best lasagne you’ve ever tasted—low fat everything, so don’t freak out—and you’ll enjoy it more if you don’t see any of the cooking process. Grab a drink, have a shower or check your email or whatever you want to do and leave dinner to us.’

‘But how can you say that? Just look at all the mess!’

‘Get out of the kitchen, Mum,’ Izzy commanded with a swish of strawberry-blonde curls. She was becoming more like her father in hair colour as well as temperament as the years passed, quick to anger but just as quick to defuse. A lot healthier than Stevie’s own anger, which tended to curl inside her like a spring. ‘We don’t need you!’ Izzy stated the obvious, giving the pasta machine a couple of decisive cranks and sending several more sheets flopping to the floor.

Jesus Christ.

Monty pressed a tin of Emu into Stevie’s hand. ‘Go and relax.’ Relax? That was easier said than done. After what she’d just been through with Fowler she felt about as relaxed as a car chase. But she was too tired for further argument. The beer was good, icy and cold. She took it with her into their living room, the stripped floorboards rough and splintery under her bare feet. With an uncommon flash of despair, she took in the room, a microcosm of the rest of their recently purchased, run-down house near the beach.

Unlike the Pavels’, theirs was single storey and authentic Federation, with many more years of neglect under its belt. That was the challenge, Stevie liked to think, of putting it to rights, making up for the sins of the past. The beauty of art was in its imperfection. With this in mind she’d opted to keep the original character of the house as much as practically possible. Crooked doors, sloped floors, the outside dunny, would remain. Obvious dangers like the sagging veranda roof and floor would have to be fixed up; the electrical wiring replaced, the plumbing modernised. It would be a long, painstaking job. In some ways the process was much like the circuitous road she and Monty had taken to arrive at this point in their lives. The house they would do together; it was their future.

The renovation plans were with the council now, waiting for the official stamp of approval before the structural changes could commence. Stevie had been doing what she could to make the place more comfortable, though none of it was necessary in this time of limbo. But pulling up mouldy carpets, stripping wallpaper and painting selected parts of the outside at least gave her restless energy some direction. Monty had said it was a useless exercise, a waste of time, seeing the builders would probably destroy most of her hard work. But she’d bulled ahead regardless and had so far enjoyed every minute of the process.

Her workstation was tucked into a corner of the lounge room. The study was only big enough for one desk and Monty dominated that. His need was greater as he worked mostly from home at the moment, writing reports for the Corruption and Crime Commission, a desk job to lead him gently up to his heart bypass surgery—if he went through with the operation, that is. He’d pulled out a couple of months ago using the state of their new house as an excuse. And he’d given Stevie no guarantees that he’d go through with the rescheduled operation either, leaving her in another form of limbo.

This one she filled with police work.

Her squad had recently arrested three Perth men involved in an international paedophile ring. The highly publicised court case demonstrated that it was not as easy as it used to be for predatory scum like these to hide on the Internet. She had spent the previous week in court, using the weekend for catching up on paperwork and team meetings at Central. The end was in sight, the prosecution going well, with most thinking they’d have a verdict by the end of next week. When her part was finished, further legalities would be handed over to the Australian Federal Police and the appropriate international authorities, and then she would commence three weeks of well-deserved leave.

Her desk was even more of a mess than usual. It looked like Izzy had been playing here again despite its out-of-bounds zoning. While she waited for her computer to boot up she attempted to create some order in the chaos, sliding Lego pieces into their box, picking up scattered crayons and textas. At least Izzy had had the foresight to protect the desk with a newspaper, Stevie thought, until she saw the page it was open at—the personal columns. Various lurid pleas and advertisements had been singled out and decorated with rainbow borders, love hearts and stars. Shit. She could only hope Izzy hadn’t been able to read any of it. Imagine if she’d planned on taking this artwork to school for show and tell?

2 hot chicks wet and waiting

Buxom blonde eager for your call...

Asian babes for all tastes

She snatched the paper from her desk and crushed it into a tight ball. Christ, she thought, I’m officer in charge of the cyber predator team and I can’t even keep this junk out of my own home, away from my own daughter. Although this wasn’t quite what she dealt with at work, the core elements were still the same, it was all a question of exploitation. Sometimes she wondered what chance in hell they had in stemming this flood.

She looked at the picture of Izzy on the mantelpiece. It was her first day at school, her school dress stiff and new. The wide, gap-toothed smile seemed to say, look at me, I’m about to take over the world. Like her dad before his health scare, she thought she was ten feet tall and bullet-proof. Stevie saw a row of little faces in the photo album of her mind, exploited little boys and girls she’d come across during the course of her career, many who would have once been like Izzy. Her mind went to the abandoned Pavel baby—God, how could she protect them all?

She took a swig of beer and tried to calm down. The day had left her overwrought. Things weren’t all doom and gloom, she tried to console herself; her team in the cyber predator unit had proved that the system could work.

She scrolled through her mail and found the memo telling her what time she was expected in court tomorrow. It looked like it was to be an all day session, which meant nearly ten hours of skirt-suit and heels. Shit.

Luke Fowler’s face filled the TV screen in their bedroom, pleading to the public for information regarding the whereabouts of Delia and Jon Pavel. The woman at the deli thought they sounded Russian: close—the newsreader said they were Romanian. Photos of the couple were broadcast along with their car rego and a picture of a green Jaguar similar to the one missing from their garage.

Earlier, between bites of lasagne—Monty had been right, it was one of the best she’d ever tasted—Stevie had recounted the details of her afternoon, including her brief imprisonment in the upstairs bedroom.

‘Good old Blinky Bill, coming to the rescue,’ Monty said again, killing the TV with the remote and plunging them into darkness.

She wriggled further into the covers; the nights were still chilly despite the warmer days. ‘Yeah, well he may have got me out of there, but he didn’t do anything to help when I had the blow-up with Fowler.’

‘How could he? You were blatantly out of line.’

Stevie snorted. ‘I thought you at least would support me. Fowler seems to think he can get me sacked for tampering with a crime scene.’

‘Bullshit, it’ll just get brushed under the carpet. You’re the hero of the hour, the flavour of the month, walking on bloody water in fact.’

Ice clinked as he drained the last of his whisky then thunked the empty glass upon his bedside table—more than a little drunk, she suspected. He shouldn’t have been drinking so close to his operation, but she couldn’t chastise him now, not when he was saying things she needed to hear. ‘There’s not much you can do wrong at the moment,’ he went on. ‘Milk it while you can, it won’t last.’ He said it with no bitterness, despite the uncertain direction of his own career.

She snuggled into his back. He was a large man who carried his weight well. She had always thought he was fit too, despite the cigarettes. Until the onset of angina last year, he had jogged along the beach most mornings. It was hard to reconcile this outwardly fit body with its inner frailties.

‘I managed to get a bit more from Trotman when Fowler finally climbed back under his rock,’ she said. ‘According to the people in the street, neither of the Pavels has been seen for four days.’

‘The baby can’t have survived alone for four days.’

‘I know that. But the date corresponds to when Jon Pavel was last seen at work and Delia was seen at the supermarket. It doesn’t necessarily mean that was when they last tended to the baby, though going by the state of him I’d say he’d been on his own for some time. ’

‘What does Jon Pavel do?’

‘Businessman.’

Monty grunted. ‘That covers a multitude of sins.’

‘Runs a couple of restaurants in West Perth and a nightclub in Fremantle.’

The phone by their bed rang. Monty swore. Stevie groped for the light and leaned over him to answer it.

With no preamble, Skye gave her a rundown on baby Pavel’s condition. She said he was improving and the doctors were cautiously optimistic he’d get through the physical ordeal with no lingering ill effects. ‘But what about his mental condition?’ Skye said with a hitch in her voice. ‘That’s what I want to know. Can you imagine the psychological effect this will have on him? I mean, the poor kid was obviously adopted in the first place, so who knows what hell he’s already been through?’

Stevie sat up in bed. ‘Adopted? Who told you that?’

‘I don’t need to be told, it’s obvious. I noticed it straight off, didn’t you? The kid’s Asian.’

Stevie paused and thought back to their discovery. Yes, come to think of it, she had noticed Asian features under the dirt and grime. But as she hadn’t known anything about the child’s parents at the time, she hadn’t given the matter much thought. The penny should have dropped when the deli woman mentioned that the parents were eastern European. She chided herself—she was usually more on the ball than this. Just as well this wasn’t her case, that her leave was almost due. Monty, the cyber-predator case, the house; the stressors were adding up. She was more tired than she’d thought.

With her hand over the receiver, she told Monty Skye’s news. He lay on his back with his hands under his head and stared at the ceiling, his face mirroring her own perplexed look.

Stevie listened to Skye a while longer and tried to reassure her that everything was being done to locate the baby’s parents. ‘She’s not handling this very well,’ she said to Monty when she finally extracted herself from the phone. ‘This baby business has really upset her, she’s a sensitive soul.’

Monty turned and raised an eyebrow as if to say: and you’re not?

‘At least I can detach,’ she said, flipping the light off again. Despite almost half an hour under the hot shower, she could still detect the sour odour of the baby on her skin. In some ways, she reflected, its associations made it worse than the scent of decay.

Monty said, ‘You’ve always said Skye was a bit, what was it, unbalanced?’

‘No, not unbalanced, just highly strung and with a keen sense of moral justice.’

‘Sounds like someone else I know.’

She didn’t rise to the bait. ‘I get the feeling Luke Fowler and Skye know each other. She certainly doesn’t seem to have much faith in his abilities. There’s some history there, I’m sure of it. He strikes me as a bully—he’d better not be giving her a hard time over this.’

‘I’ve come across him once or twice; did a course with him in Adelaide. He seemed okay to me.’

‘He might be okay to prop up a bar with after a day of lectures, but you’ve never had to actually work with him.’

‘True. He must have seriously pissed off someone to land Peppy Grove. Never mind, if it does turn out there’s a homicide behind this case, it might end up on my desk at SCS, which means Peppy Grove can be ousted.’

‘You’re not on active duty,’ she reminded him.

‘But at least I’ll be able to find out what’s going on and you won’t have to rely on gathering information by devious means.’

The conversation faded; they lay in silence. He rolled over and she spooned into his solid back once more. His pragmatism, though sometimes an irritant, was a comfort tonight. She wondered again why it had taken her so long to agree to set up house with him, wondered how she’d ever thought she could do without him.

But then her thoughts drifted to the negative, the dialogue in her mind of ‘what ifs’ that refused to shut down. Monty’s upcoming heart procedure was a dangerous operation. The blockage was in the left anterior descending artery, the one the doctors called ‘the widow maker’. What if the operation was a failure? He could become an invalid or die under the anaesthetic; which was something he’d probably prefer, she contemplated morbidly. And they weren’t married, even though they were engaged and they lived together—would she still qualify as a widow? She wondered if she’d ever be able to revert back to the old Stevie, the one who didn’t need him or any other man in her life. The thought of being without Monty grabbed hold of her and shook her like a pitbull.

His muscles began to relax, his breathing to deepen. She breathed with him. Images of neglected babies, lonely old women, letters of dismissal and flatlining heart monitors faded. Finally she began to drift off.

Then Monty started awake with a sharp intake of breath. ‘Stevie, I’m so scared,’ he said. (Image 5.1)

Imgae 5.1