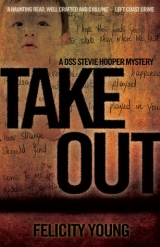

Текст книги "Take Out"

Автор книги: Felicity Young

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Table of Contents

PRAISE FOR FELICITY YOUNG

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LIST OF SHORTENED FORMS USED IN THIS NOVEL

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

OTHER STEVIE HOOPER TITLES

PRAISE FOR FELICITY YOUNG

An Easeful Death is a delightful pot pourri of police corruption, injustice, tangled emotions, treachery and misunderstanding— Mary Martin website

An Easeful Death is bound to keep you up at night— Scoop Magazine

[An Easeful Death] is tight and well-written— Adelaide Advertiser

An Easeful Death is an exciting whodunnit page-turner from a talented West Australian writer, and a welcome addition to Australian crime fiction— Western Suburbs Weekly

Felicity Young is an intriguing new addition to the upper echelons of Australian thriller writing... Harum Scarum is a well-crafted page turner that explores themes that concern every parent— Sun-Herald

Harum Scarum is an enjoyable read with considerable credibility—Aussiereviews.com

Harum Scarum is a gripping, chilling thriller. A page turner—www.eurocrime.co.uk

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Felicity Young was born in Hanover, Germany, in 1960 and went to boarding school in the United Kingdom while her parents were posted around the world with the British Army. When her father retired from the army in 1976 the family settled in Perth. Felicity married at nineteen while she was still doing her nursing training and on completion of training had three children in quick succession. Not surprisingly, an arts degree at The University of Western Australia took ten years to complete. In 1990, Felicity and her family moved from the city and established a Suffolk sheep stud on a small farm in Gidgegannup where she studied music, reared orphan kangaroos and started writing.

Having a brother-in-law who is a retired police superintendent, it was almost inevitable she would turn to crime writing. Felicity Young’s first novel, A Certain Malice, was published in Britain by Crème de la Crime in 2005. An Easeful Death (2007) and Harum Scarum (2008) were published by Fremantle Press. Take Out is her third Stevie Hooper crime novel.

To Ben, Tom and Pip

And to Mick, as always, with love

LIST OF SHORTENED FORMS USED IN THIS NOVELAFPAustralian Federal PoliceAPBall points bulletinCCCCorruption and Crime CommissionCODcause of deathDCPDepartment for Child ProtectionEEGelectroencephalogramET tubeendotracheal tubeGBHgrievous bodily harmICUintensive care unitID cardidentity cardMCISMajor Crash Investigation SquadOICofficer in chargePDQpaint data queryRANRoyal Australian NavySCSSerious Crime SquadSOCOscene of crimes officerUNIFEMUnited Nations Development Fund for WomenUWAThe University of Western AustraliaWACAWestern Australian Cricket AssociationWAPOLWestern Australian PoliceTable A

PROLOGUE

Mai and the other planters follow the farmer and his ‘mechanical buffalo’ as it chug chugs along, ploughing the ground into soupy mud. They separate the tied bundles of rice seedlings and then plant them individually into the furrows. It is back-breaking work, but neighbour helps neighbour. Soon a carpet of dazzling green will cover the paddies. The rice shoots will grow, the weather will dry the seeds and after the harvest there will be much celebrating in the village.

Mai thinks of the fun times to come and they are the only things that keep her going. She works alongside her mother and sisters. Her father leaves before the short lunch break. He tells them his back is sore. Mai’s mother says nothing, but Mai knows she will be blushing with shame under the scarf that covers most of her face. With the help of these neighbours their own family paddy was planted several days before.

They break for lunch, flick the mud from their feet like cats and find a patch of ground a little less soggy than the rest to sit on. Mai’s three younger sisters eat sticky rice and play jacks with the other children on a scrap of timber. Mai rolls her shorts further up her legs and steps into the tepid water of the drainage ditch to hunt for frogs and small fish to add to their evening meal of steamed rice. The liquid movement of a snake glides across the skin of her calf. She stands rigid, like a water bird on one leg, and concentrates on the buffalo on the bank. The buffalo’s ears flick ineffectually at the surrounding halo of flies. Grass shoots are stretched and snapped by his lips and tongue, teeth crush and grind upon the pulp. The scent of his breath sweetens the metallic tang of mud from the surrounding fields. Damp air presses against Mai’s skin. In the dishwater sky, heavy clouds roil. Only when she is sure the snake has gone, does Mai move again and continue with her lunchtime hunting.

When the day’s planting is finished, Mai and her mother and sisters get a lift in the farmer’s pick-up to their house in the village on the banks of the river Pai. The house is built on stilts to protect it from floods. A colourful assortment of open umbrellas hangs underneath the floor and sways in the weak breeze. Bicycles lie on top of one another under the shelter, chickens perch on rusty handlebars. All around the village, buffalos bellow at the approaching storm.

A satellite dish on the tin roof makes the roof tilt to one side. Mai’s father says they are a privileged family. No one else in the village has a satellite dish and because of this he is a very big man.

But there is no noise from the TV tonight. Mai climbs the steps to find her father with the usual can of Singha beer in his hand, sitting on a fruit crate watching an Elvis Presley movie with the sound turned down. A stranger in an embroidered silk dress sits on a crate next to him. She wears dainty red shoes and carries a bag that sparkles like diamonds under the single light globe. The woman must be very rich: the TV doesn’t get turned down for anyone.

Her mother places her hands together and gives the woman a little bow. Her father hauls himself up from the crate. ‘See this woman, Mai?’ he says. ‘She used to live in a village like ours and came from a poor family too. She went to Bangkok and made lots of money.’

Mai bows to the woman as her mother has done.

‘Would you like to come to Bangkok with me, Mai? Would you like to be rich like me?’ the woman asks in a high fluting voice.

There is a long silence. Mai’s mother starts to cry. Mai doesn’t understand why. This is the most exciting thing she has ever heard and she finds herself gulping air like a frog. She is twelve years old and cannot take her eyes off the woman’s diamond purse. She wants so badly to have a purse like that.

‘You go with this woman, Mai,’ her father says, ‘and you will never be hungry again. You will have all the jewels and fine clothes a young girl could ever want.’

Mai glances across the room towards her three younger sisters. The food she has caught in the field today will never fill those hungry bellies. Her own belly begins to growl; perhaps it is the spirits giving her a sign. She lowers her eyes and nods her head to her father.

He pulls her into his arms. His skin is slick and he smells of smoke and beer. ‘You are a good girl, Mai. You go with this woman. Help yourself and then you can help all of us.’

Mai knows of girls in other villages who have been visited by beautiful strangers. Their families boast about it, saying how rich the girls have become. Mai realises she must have been very special in her previous life to be chosen as one of the lucky few in this one.

Her mother hugs her. ‘You will come back to visit?’

Mai looks to the beautiful stranger for an answer. The stranger nods her head and says ‘yes’ with a solemn promise.

As Mai is led to the door by the stranger’s small manicured hand, she hears her father say, ‘DVD players are going cheap in the market. I can buy one now.’

MONDAY

CHAPTER ONE

The dead cycad might look like a rusty buzz-saw in a pot, Stevie thought, but it was hardly a portent for disaster.

‘Have you been inside?’ she asked Skye, who had joined her on the front porch. Stevie’s fingers grazed one of the plant’s leaves. ‘Ouch!’ She pulled away, beads of blood welling along the small cut.

‘Tetanus up to date?’ Skye asked.

Stevie pulled her stinging finger from her mouth. ‘Yes, Nurse Williams.’

‘If I’d had the guts to go inside,’ Skye went on, ‘I wouldn’t have bothered calling you, would I?’ She gave a characteristic eye roll that made Stevie smile despite her irritation. ‘Mrs Hardegan’s positive no one’s been home for days. I mean come off it, look at all this.’ She waved her hand at the overflowing letterbox and the rolled newspapers cast about the lawn.

‘And the grass needs a mow,’ said Stevie, ‘I can see all that, but why didn’t you just wait for the local cops?’

‘I told you,’ said Skye. ‘They never showed. ‘C’mon, you owe me. Let’s get this over with. I’ve still got another three home visits to make and she’s watching.’ Skye tilted her head towards the squat pre-war bungalow next door. Stevie caught a shadow of movement from a window, the snap of venetian blinds. With a resigned sigh she gave the lion-head doorbell three sharp jabs.

Skye fumbled in the pocket of her uniform for the key Mrs Hardegan had given her and reached for the doorknob. ‘I rang before and got no answer, had a look around the garden, the back shed, looked through the windows—there isn’t anyone about.’

To their surprise the door opened under her touch.

They found themselves in a cool front entrance with a high ceiling. A stained-glass skylight shone down on them and a black and white tiled floor chequered its way down the passageway to the left and right. There were plenty of larger mansions in the area, but this Federation-style reproduction was the biggest in the block. Stevie regarded the spacious lounge room ahead. Two modular sofas gripped the walls, the type found in airport lounges or hotel lobbies, not really designed for lounging. Not even a coffee table filled the void between them. The room was bare: there were no paintings, no TV, books or magazines. Stevie had seen display homes that looked more homey.

‘Police! Is anyone here?’ she called out, her voice echoing down the passageways.

No response.

‘Nice place,’ Skye mumbled.

‘What exactly did the old lady say?’ Stevie asked as they headed down the right hand passage, footsteps scuffing on the gritty tiles.

‘Mrs Hardegan said she hasn’t seen the couple for several days, and they always tell her if they’re going away. She likes to keep an eye on things. It gives her something to do.’

‘Good neighbour,’ said Stevie, glancing into an open-plan dining room that contained a dusty antique table and no chairs. A picture window, designed to capture rolling farmland or sweeping cityscape, revealed a cramped backyard.

‘She said she’d got her son to call the local cops—several times—and they promised they’d look into it, but they haven’t. I tried them too, also with no luck. I reckon the old dear might’ve cried wolf one too many times.’

‘So you called me instead.’

‘Mrs Hardegan’s recovering from a serious stroke and I don’t want her having another. She’s been getting more and more anxious over this and I can’t see the harm in putting her mind to rest. Besides,’ Skye added with an ironic smile, ‘we were planning on catching up anyway.’

‘This isn’t exactly what I had in mind.’ Stevie pulled at her paint-spattered overalls. ‘I was doing the eaves of my house.’

Skye shrugged. ‘Give a girl a spanner.’

Stevie thumped on the closed door of what she assumed to be the master bedroom, expecting and receiving no reply. ‘Has Mrs Hardegan told you anything about the couple?’

‘Delia and Jon Pavel, early thirties, filthy rich.’

Stevie opened the door and saw an unmade bed, scattered shoes, dirty carpet. The windows were shut and the room smelt sour.

‘Filthy seems to be the operative word,’ she said as she approached the bed. She poked for a moment among the tangle of forget-me-not blue sheets and floral pillows, noting the absence of doona or blankets.

Skye tugged at an earlobe peppered with empty holes. ‘Stevie, maybe we shouldn’t be doing this…’

Stevie barely heard her. She was in full cop mode now and it was too late for second thoughts. She indicated an open satin box on the dressing table containing a magpie’s nest of jewellery: gold chains, silver, diamonds and pearls, ‘Look at all this—they obviously haven’t been robbed.’ Nodding to a plasma TV on the wall opposite the bed she said, ‘And that would’ve been easy enough to take.’ A knot formed in the pit of her stomach. Robbery was now the least of her concerns. ‘Wait outside if you like, Skye.’

‘No, no, you might need me, I’d better stay.’ A tremolo underscored Skye’s earlier confident tone. A uniformed constable would be a lot more useful than this skinny girl with the dark rings under her eyes, Stevie thought as she flicked her friend an unenthusiastic smile.

They picked their way around piles of unwashed clothes in the doorway of the ensuite bathroom. Scattered beauty products oozed over the vanity, blobs of dried toothpaste dotted the green marble top. The taps of the claw-foot bath were edged with slime, the tub ringed greasy grey.

Skye shuddered. ‘Looks like my sister’s bathroom,’ she said as she toed a towel with a white Doc Marten, releasing an invisible cloud of mould into the air.

‘What you might expect from a teenager, but not a wealthy couple in their thirties,’ Stevie said.

A tap dripped a steady pulse into one of the double basins. The basin would have flooded over if the plug had been more securely rammed in the drain. Stevie reached for the faucet and stopped the flow. ‘Their toothbrushes are still there, his shaving stuff, her make-up. Maybe they had toilet bags packed and ready to go?’

‘Maybe. I only saw one car in the triple garage.’

‘What kind of car?’

‘A new Range Rover, very dirty, filled with burger wrappers and junk. Why bother going to the tip when you can carry it around with you?’

They continued to look around the east wing of the house, taking in the few pieces of expensive but carelessly arranged furniture, the layers of dust and the rippled oriental runners in the passageway. It seemed to Stevie as if the trappings of wealth were of little consequence to these people; things in this household were taken for granted, neglected. They passed a sweeping wooden staircase. ‘We’ll search downstairs first,’ she said.

The family room and kitchen were cavernous. Stevie folded her arms and slowly pivoted on her heel. There wasn’t enough furniture to fill the room or muffle their footsteps. There were no curtains on the windows or ornaments on the jarrah fire surround other than a mute carriage clock, hands stopped at 10.15. Possessions tended to give off echoes to Stevie but the few objects in this room told her nothing. All was silent except for the faint humming of the fridge and the popping of blowflies against the windows.

She ran a finger across a windowsill. The paintwork looked fresh under the dust. ‘Have the Pavels lived here long?’

‘Long enough for Mrs Hardegan to get to know them. The house is obviously fairly new, not bad for a reproduction.’ Skye pointed out a row of brass light switches and the tracked ceiling lights. ‘Expensive, too.’

Stevie’s eyes were drawn to the adjacent kitchen area some metres away. The rancid smell of old food became sharper as she zeroed in on the kitchen table. Laid for two, it held the remains of an unfinished meal—TV dinners by the looks of the empty food packets on the granite bench top. Both plates contained thin slices of drying beef, crusty cauliflower and half nibbled cobs of corn. Flies skated on ponds of solidified gravy splashed across the tray of a baby’s highchair.

The knot in Stevie’s stomach tightened. ‘ Mary Celeste, ’ she whispered.

‘What?’

Stevie waved her hand. ‘Forget it.’ As she walked she kicked a scattering of shrivelled peas across the floor. A glass of pale liquid teetered on the table’s edge, too close for comfort. She lifted the glass to her nose and sniffed.

‘Stale wine,’ she said, sliding the glass into a less precarious position. ‘Looks like this food has been here for several days.’ She pointed to the table. ‘The meal’s only half finished, the chairs are skewiff, as if someone left in a hurry.’

Heat still radiated from the electric oven. In it she found a baking dish containing several charred spheres.

‘They never got their pies,’ Skye said, voice hushed as she pointed out the carton of ready-made apple pies next to the other empty food containers.

Stevie replaced the oven tray and chewed on her bottom lip, trying to make sense of it all. At once she became aware of a strange sensation at the back of her neck, a warm breeze, the feathering of a breath.

Her sudden turn towards its source caused Skye to clap herself on the chest. ‘Holy shit! Don’t do that!’

Stevie spotted the open gap in the sliding window behind the sink and let out her own pent-up breath. ‘Sorry, I thought for a minute someone else was in the room.’

‘Look, I don’t feel right about this—this place gives me the creeps,’ Skye said, drawing a breath and exhaling with an unmistakable wheeze. ‘I think we should leave and call the proper police. I reckon they’ll listen to you rather than me.’

The ‘proper’ police, jeez.

‘I’m not pulling out now,’ Stevie snapped back. ‘Wait outside if you like while I check out the rest of downstairs.’

Skye reached into her pocket for a Ventolin inhaler, took a couple of puffs and sidled a step closer to Stevie.

Two of the bedrooms in the west wing were empty and dusty with spider webs parachuting from the cornices. Another room served as a study. A computer on a fake antique desk stood next to a single bed with nothing on it but a bare mattress. A scraggly bottlebrush from the garden bed outside scratched against the window. Stevie cringed at the sound. Blood-red flowers pressed against the glass—as if anyone or anything would want to get into this desolate, inhospitable house.

There was still one room left to check at the end of the passageway, next to a bathroom. She sniffed at the odour leaking through the gaps of the closed door and felt nausea rise. Skye dug her bitten fingernails into Stevie’s arm. The door creaked as Stevie eased it open. She drew a sharp breath.

‘Oh my God,’ Skye said.

CHAPTER TWO

The room was as bare as a prison cell. The only item in it was an old safe cot of the style now deemed politically incorrect. Like an old-fashioned meat safe its walls were made of tough flyscreen topped by a heavy wooden lid.

The cot reeked, the bedding a jumble of urine-soaked sheets, flyscreen walls clogged with lumps of faeces. A soiled disposable nappy had been flung to the far end of the saturated mattress.

The naked baby inside lay still.

With trembling fingers, Stevie fumbled with the latch and flung back the door, making the wooden frame rattle.

Skye pushed her aside before Stevie could reach for the child. ‘Wait a minute,’ she said. Leaning over the wall of the cot she gently inserted her finger into the baby’s mouth. ‘Airway’s clear but the inside of his mouth is dry—he’s very dehydrated.’ Her finger pressed the side of his neck. ‘Pulse rapid, but not too bad. We’re not too late.’

The baby stirred, whimpered and sucked his thumb with increasing vigour. Skye ran her fingers over his dark, matted hair and looked desperately around the room.

‘Here.’ Stevie grabbed a cot blanket from the floor and handed it to Skye who wrapped it around the baby and clasped him to her chest. ‘Let’s get out of here,’ Stevie gasped, as the movement of the bedclothes disturbed the foul air.

In the kitchen they made the necessary phone calls. Stevie reported the incident to the local police, stressing the emergency and then took the baby from Skye so Skye could call for an ambulance. After consulting with the on-call medico Skye decided the baby could be given a small amount of water. She filled a cup from the kitchen tap and put it to his lips. He drank greedily, snatching at the cup with stained fingers, mewling like a kitten when she wouldn’t let him hold it himself. ‘Poor little bugger’s still thirsty,’ she said as she pulled the cup away and placed it on the kitchen table. ‘We’d better not let him have any more, he might vomit it up—this should get him by until he reaches hospital. They’ll need to know how much fluid we gave him, put an IV in.’

The baby didn’t have the strength to yell; his eyes were sunken, his skin hot and dry. He soon gave up his fight to reach the water and flopped his head against Stevie’s shoulder. ‘How could anyone leave a baby like this?’ Skye asked, rubbing soothing circles on his back, eyes glistening with unshed tears.

Don’t go sentimental on me now, Stevie thought. ‘Here take him.’ She passed the baby back to Skye. ‘Wait in the fresh air for the ambulance, I want to make sure no one’s upstairs.’

She had a quick look around the upstairs of the house, relieved to find just three deserted, almost empty rooms.

Back in the family room rays of light shone through the French doors, highlighting the dusty coating of the tiles, sticky patches and faint footprints. Stevie slowly examined the tracks on the floor from different angles, all the while conscious of the smell of the baby on her clothes. It was during one of these shifts of position that she noticed a clean area of tiles in front of a leather chesterfield, as if the tiles had recently been washed. She pushed the couch back, the sudden draft making the dust-bunnies underneath tumble. Earwigs hiding from the light scampered away across ominous brown splats. She dropped to her knees to examine the stains. Could be spilled Milo or tomato sauce; could be dried paint. Or blood.

It was tempting to search the floor for further evidence, but fear of contaminating a possible crime scene held her back. French doors led from the family room to the small back garden; she’d cause less damage out there, she decided, as she opened the doors up.

The walled garden seemed as badly kept as the inside of the house, although the surrounding flowerbeds, crowded with roses as tall as Stevie herself, suggested a time when it had been well maintained. Somewhere in the distance she heard the wail of an ambulance.

At the swimming pool’s fence she stopped. An ominous bulge pressed up from under the pool’s cover.

Shit.

The gate creaked as Stevie opened it, hurrying across the weed-choked paving to the cover’s reel. The pool surface gradually appeared as she wrestled with the stiff mechanism, and she found herself breaking into a sweat despite the mild temperature. Leaves and dirt swished from the bubbly blue surface, leaving black scum upon the green water. The reason for the bulge, a pink lilo, sprang from the confines of the cover. Globs of algae bobbed on the water’s surface next to the body of a disintegrating blue-tongued lizard. It was impossible to see through the murk to find out what else might be down there and she decided she didn’t want to know either; the rest of the job could be left to the police search team. Finding an abandoned baby was enough for one day.

She heard the ambulance pulling up outside the gate and walked a brick-paved path to meet it at the front of the house. The baby had fallen asleep against Skye’s shoulder. She continued to rub his back, cooing something tuneless under her breath. Stevie explained the situation to the ambulance attendant and asked where the baby would be taken.

‘Straight to PMH. Lucky you found him when you did.’

Skye pushed past him into the back of the ambulance before he’d finished swinging open the doors and settled on the seat with the baby tight in her arms. She cut the man off before he could voice his protest. ‘I’m a nurse, I’m going with him.’ She swung defensively to Stevie as if expecting to be challenged by her too.

Stevie shrugged. ‘Good idea, you can tell me what the doctors say.’

Skye held up a hand as the doors were closing. ‘Look in on Mrs H for me, Stevie, make sure she’s okay, yeah? And call me: I want to know what’s going on here—none of your secret police business.’

Easier said than done, Stevie thought. This was out of her jurisdiction; she’d be lucky if the local police confided in her at all. She pulled her blonde ponytail through her fingers as she watched the ambulance speed away, and tried to remember which police division covered the Peppermint Grove area, pondering the likelihood of knowing anyone in it. No names sprang to mind.

As she stepped out of the front garden gate, a small colourful object caught her eye. She squatted down to take a closer look and found a silk-covered button. Making a mental note of its location she reminded herself to point it out to the police when they arrived.

It had been about fifteen minutes since her call and there was no sign of them yet. A dark slit appeared in the venetians of the house next door. Perhaps Mrs Hardegan was anxiously waiting for the police too? Skye had asked her to check up on the old lady—surely a quick word wouldn’t do any harm?

Rows of peppermint trees bordered the wide street, filling the air with a minty odour cut through by the tang of the sea to the west. Mrs Hardegan’s was one of the few untouched houses left in the area, most having been extensively renovated or knocked down and replaced by modern concrete monoliths and elegant reproductions such as the Pavels’. Her Californian bungalow was characteristically squat with tapered columns supporting a heavy front veranda, and a gabled roof with winking leadlight windows. Stevie detected the smell of camphor before the front door was even opened.

‘Where have you been, boy?’ the old woman demanded. She wore a simple linen dress enlivened with screen-printed green fish and secured with a tight leather belt. She stood ramrod straight, her bright, level eyes fixed unwaveringly upon Stevie. Stevie may have been wearing workman’s overalls, but she didn’t think her gender was that ambiguous. She began to explain. ‘Mrs Hardegan? I–’

‘We’ve been waiting here for days. What’s wrong with the smudgin’ fullets these days, why so long?’

It took a moment for Stevie to realise the woman’s peculiar speech must be the result of the stroke Skye had mentioned. It might also explain why she’d been unable to call the police herself, getting her son and Skye to do it for her.

‘I’m a friend of Skye’s, Mrs Hardegan.’ Stevie consciously slowed down her usual rapid-fire speech. ‘She asked me to look into the Pavels’ house for you. She said you hadn’t seen them for a while and were worried about them. I am with the police, but not from Peppermint Grove. The Peppy Grove police are on their way.’

‘A lovely boy, but the others are useless, quite useless. You’d better come in, have a cup of tea and tell us what’s going on.’ Despite the oddness of her speech, she had the cultured pronunciation of another era, almost English but not quite. Newsreel ABC.

Mrs Hardegan turned and clasped one of the bookcases in the dark hallway. As she eased herself down the passageway, Stevie noticed one leg lagging slightly behind the other. Seeing no sign of a Zimmer frame or stick Stevie instinctively reached for the woman’s elbow, but the well-intentioned gesture was shrugged away with an impatient scowl. On the wall above a bookcase, a black and white photo of a young Mrs Hardegan caught Stevie’s eye; the hooked nose was unmistakable. She was dressed in the uniform of a wartime RAN nurse—it figured.

Mrs Hardegan led Stevie past several closed doors to a lighter, self-contained room with kitchenette at the back of the house, where it appeared she did most of her living. Recycling was sorted and stacked in tidy piles on one of the benches. The surfaces of the kitchenette were clean; soapsuds popped on the drying plastic dishes spread across the draining board. The single bed in the corner of the room was made after a fashion, the lumps disguised by an intricately embroidered cotton counterpane. Stevie found herself wondering how long it had taken the old lady to make the bed, how frustrating the disability must be to someone who probably required everything around her to be shipshape. Every free surface of the room was crowded with various arts, crafts and sewing paraphernalia: crushed tubes of fabric paint, bottles of varnish, glue, jars of bristling paintbrushes. A wooden contraption, like an old printing press, stood near one of the windows. It would be used for screen-printing, Stevie guessed. Several bright cushions of the same fish design as the old lady’s dress were arranged in a precise line down one side of the bed.

An open door led into a bathroom. Stevie glimpsed a toilet and railed bath before Mrs Hardegan moved with surprising speed to close it.

‘Bloody Japs!’ The mechanical voice made Stevie whirl towards the source, a parrot, hanging in a dome-shaped cage from a ceiling beam toward the back of the room.

‘Hello, who’s this?’ Stevie said as she approached, resisting the urge to poke a finger through the bars. The parrot stared back. It had bright black eyes and a beak similar to its owner’s—it could probably shear a finger with a single snip. Bald in places, its patchy arrangement of feathers looked as washed-out as a favourite summer shirt.

‘Captain Flint, our feathered friend,’ Mrs Hardegan said.

The tea was made with only a few minor mishaps—Stevie given three lumps of sugar when she asked for none—and settled by Mrs Hardegan on a tapestried footstool in front of a high-backed easy chair next to the window. One side of the Pavel residence was visible from this vantage point and the binoculars resting on a shelf nearby were no doubt used for further surveillance.