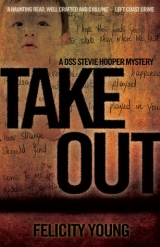

Текст книги "Take Out"

Автор книги: Felicity Young

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

SUNDAY

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Most of the flowers in the vases had died and the green tinge of stagnant water overrode the smell of disinfectant in the hospital room. ‘It’s a sign,’ Monty said, wrinkling his nose. ‘I knew it; I’ve outstayed my welcome.’

The surgeon, following closely on Stevie’s heels that morning, had announced that Monty could go home the next day.

Stevie had been waiting anxiously for days for Monty to be given the all clear. Now, after everything that had happened, she wished he could remain in hospital just a bit longer, out of harm’s way. At least until she could drag herself from the mire into which she felt she had sunk. It didn’t seem to worry him that they would have to stay with Dot, but it worried her. Despite her bricks and mortar mantra, it felt as if they’d taken a step back in their relationship.

While her mind had been shooting off at dozens of tangents ranging from people traffickers to medications, physios to paedophiles to pornographic magazines, house fires to change-of-address notifications, Monty’s thoughts were focused on the minibus crash. He turned from where he had been standing at the window watching the traffic crawling below, hands deep in his dressing gown pockets.

‘Any news about the two dead men from the bus?’ he asked, lowering himself gingerly onto the hard chair alongside Stevie’s.

‘The fingerprint results are back,’ Stevie said, rocking back with her feet resting on the bed, attempting a look of relaxed calm. ‘The one with the slashed throat was Rick Notting. He’d been in and out prison for most of his life for a variety of charges ranging from GBH, possession with intent to sell and, in later years, procurement. The other guy, Jimmy Jack Robinson, is a known pimp, but clever or lucky enough to have avoided doing time, so we don’t have much on him.’

‘Where are they from?’

‘Both of their driver’s licences list false names and addresses. But through their real names and social security records, Fowler has been able to trace their last known abode as a Northbridge address with Robinson’s name on the lease. When Fowler and his people arrived, the joint was being thoroughly gone over by a group of professional cleaners who told them a woman phoned the job in and paid by credit card. She said her name was Joyce Grenfell.’ That name. Stevie tugged at a thought that remained hidden. How many people out there, under a certain age, would even know who the old British actress was?

‘Someone was having a laugh at our expense?’ Monty said.

She frowned, still puzzled by the choice of alias. ‘Yeah, surprise, surprise—but the transaction did go through.’

‘Stolen card.’

‘Fowler’s following that lead too.’

‘What about the knife?’

‘We think it belonged to Robinson—his prints are all over it. Wayne put word out on the street for information and one of his sources came back to him saying they vaguely knew of this Robinson guy—Wayne said his informant was very careful about distancing himself—said that Robinson always carried a distinctive fishing knife...’ Stevie paused, pulled at her ponytail. ‘But another print, also isolated from the handle, belonged to one of the girls.’

Monty’s eyebrows shot up. ‘They think one of the girls might’ve done Rick Notting in?’

Stevie shrugged. ‘Melissa Hurst hasn’t finished the autopsy, but I guess when she examines the throat wound, she’ll be able to work out the angle of entry. We might be able to figure it out from there.’

‘Do you have a seating plan for the bus?’

‘No one was wearing seat belts, bodies were flung all over the place, with the two men and the body of a girl ending up outside. SOCO and MCI are dealing with the problem now.’

‘Wouldn’t the steering wheel have stopped the driver from going through the window?’

‘The bus door slid open, they think the driver fell out.’

Monty got up from his chair and began scooping up the get well cards that filled every available surface in the room. After glancing through them all, he put a handmade creation from Izzy into his pocket and tossed the others into the bin. ‘You and Fowler getting on a bit better these days?’

Stevie made a balancing motion with her hands.

‘Sounds like he’s doing a good job on all this following up. Angus was in to see me yesterday; he’s still pissed with you, even if Fowler isn’t.’

‘He’ll get over it.’ Stevie moved over to the bin, pulled out the discarded cards and shuffled through them before tucking them into her bag. Monty made no comment except to turn his eyes upwards.

‘Back to the Northbridge house,’ she said, thinking it was a good thing they still had so much to talk about; the last thing she wanted to discuss now was office politics. ‘It was obviously being used as a brothel, fitted out with several cubicles as well as a dormitory-like bedroom and a bar downstairs. Fowler managed to get hold of some prints before the cleaners wiped the place clean. Some of them matched those of Notting and Robinson; the others are still being compared to the dead and surviving girls. Which reminds me.’ She looked at her watch. ‘Fowler and I have a meeting with the interpreter in about five minutes. The doctors says one of the girls is well enough now to be questioned.’

Monty moved to follow Stevie from the room, but she stopped him with a hand upon his shoulder. ‘The girl’s been traumatised enough, Mont. She’s already going to have to face me, Col, Fowler and the interpreter—one more person will be one too many.’

Monty gave her one of his dog-in-the-pound looks. ‘Of course I wasn’t going to participate in the questioning. I was merely going to accompany you upstairs. I do need to exercise, you know.’

Stevie knew he would try get away with it if he could. No matter how much Monty had been talking about retirement, being a cop was as natural to him as breathing, and he couldn’t help himself.

He walked with her to the lifts where they met Fowler and Col and the pathologist, Melissa Hurst. Fowler explained that the interpreter was running late, but as they’d run into Hurst in the foyer just after she’d finished the autopsy on Rick Notting, they’d decided to hold an impromtu case conference. Wayne and Angus were to meet them shortly in the doctors’ common room downstairs.

‘I suppose I’d better get back to bed,’ Monty said, making no move other than to look expectantly from one face to another.

‘If I were your surgeon,’ Hurst regarded him sharply over her half-moon glasses,’ I wouldn’t want you wandering around the hospital, discharge tomorrow or not—there’s no resuss trolley in the common room, y’know.’

Monty looked down at the diminutive older woman, opened his mouth and closed it again. Turning on his slippered heel he muttered, ‘I know when I’m not wanted.’

Hurst shot Stevie a wink. They both watched as he made his way back to his room, growing taller and straighter with every step he took.

Hurst took them downstairs to the semi-deserted common room where they met with Angus and Wayne. Wayne acknowledged Stevie with a bear-like clap to her sore shoulder, which almost made her cry out. Angus gave her a smile, not quite as frosty as it could have been. ‘Sorry to hear about your house,’ he said, pulling up a chair beside her. ‘The arson squad seems to have it under control, but I still want to look into it.’

‘Me too, just as soon I come up for air. But please, Angus,’ she put her hand on his arm, ‘don’t tell Monty what caused it. He’s doing so well, a shock like this could set him back.’

‘He’ll need to know it was a deliberate attack.’

‘I’ll tell him when he’s fully recovered or when this case is wrapped, but not ’til then. Have you had any luck with tracing the man who gave the mag to Izzy?’

Angus frowned. ‘No one outside the school seems to remember seeing the man at all, can’t tell us anything...’

‘Thanks for meeting me here,’ Hurst broke in, addressing the team gathered around the table. ‘The Notting autopsy is the only one I’ve had the chance to complete so far, and I’ve still got a queue of trolleys in the basement waiting for me.’

‘Wish I was that popular,’ Wayne said.

Unsmiling, Hurst reached into her briefcase and handed out colour photos of the deceased, some taken at the scene and some from Notting’s autopsy itself.

Stevie examined the pictures, interior shots of the bus showing portions of dark-haired girls squeezed between crumpled seats and twisted metal, another girl thrown free and clearly dead. She focused mainly on a shot of Notting lying on his back outside the bus. In his case, the sadness she usually felt at viewing such scenes was absent. He reminded her of a wolf, his lupine grin eerily mimicked by the deep red slash in his throat, exposing slashed blood vessels and a gaping trachea. Flies spotted the pool of congealing blood in which he lay; the vivid stains of his shirt looked alive and creeping under her gaze. A limp male hand, presumably belonging to Jimmy Jack Robinson, was visible at the very edge of the frame, the knife on the ground between them.

Col put down the pile of photos he’d been leafing through. ‘The cause of death looks pretty obvious to me; what else have you got for us, Melissa?’

‘His blood contained a cocktail of chemicals—high doses of amphetamines, sedatives and marijuana, which could explain the randomness of the accident. The guy was as high as a kite and would have been totally out of control. And if he was the driver, well ... he was an accident waiting to happen.’

‘That makes sense,’ Angus said. ‘Pruitt’s report states there were no signs of brake marks on the bitumen. It was as if he deliberately drove straight over the ravine.’

‘But how do we know he was the driver?’ Stevie asked.

‘MCI are still busy working out body projectiles, but they think from the position he was lying in, he most probably fell out of the driver’s side door,’ Angus told her.

‘But they can’t be certain, surely,’ Wayne queried the pathologist. ‘If he was alive, might he not have moved or crawled away from where he landed when he first hit the dirt?’

‘Unlikely, Sergeant, given that his spinal cord was severed in the T3 and T4 region,’ Hurst said.

‘So he was paralysed?’

‘If he’d lived he’d have been a paraplegic from the lesion down. At the time of the accident, due to shock and swelling, he probably wouldn’t have been able to move a muscle.’

Everyone around the table paused to consider this.

‘Is it possible that someone cut his throat while he was still driving the bus?’ Stevie queried.

‘Only if someone had a death wish,’ Wayne scoffed.

‘These girls might not feel they had much to live for,’ Stevie said, exchanging a glance with Hurst, who agreed with a barely perceptible nod of her head.

‘Okay then, could Jimmy Jack have threatened him by putting the knife against his throat? It’s a sharp knife—his hand might have slipped if the bus hit a bump,’ Angus suggested.

Hurst allowed a slight smile; she enjoyed listening to the detectives trying to work it out for themselves. Stevie knew that she probably had the correct card up her sleeve, but wouldn’t produce it until she was sure every possibility had been covered, and then her word would be final. As well as Chief of Forensics, she lectured in pathology at UWA. She loved to teach, and could never let an opportunity pass her by. They had all learned a lot from Professor Melissa Hurst.

‘What about the angle of the wound?’ Angus asked.

‘Left to right slash,’ Hurst replied.

‘Left to right,’ he mused. ‘Meaning our offender was right handed.’

Stevie pushed away from the table and stood behind Wayne. ‘I need to get something clear here.’ Reaching for a butter knife from the table, she told him to hold still. With her left hand pulling back upon his forehead, she held the knife above his throat and made a left to right slashing motion.

Angus smacked his hands together. ‘I’ve been wanting to do that for years.’

Stevie pulled a disconcerted Wayne to his feet. ‘Okay, now, lie on the ground,’ she commanded. Wayne looked around the empty common room to reassure himself no one else was watching and positioned himself on the hard carpet squares as if rigor mortis had already set in.

Stevie positioned herself behind his head and went through the same motions as when he was sitting. When she’d finished Wayne heaved himself from the floor returned to his seat and flexed his shoulders. ‘Well, I hope that was worth my pain and humiliation.’

‘It was, Wayne,’ Hurst said, ‘well done. Stevie was demonstrating how similar the throat cutting technique is, irrespective if the victim is lying or sitting when the attack is made from behind. The knife wounds would be almost identical too, which means we can’t rely on them.’

‘If Notting was driving, let us assume Robinson was in the passenger seat—he did go through the front window—so if he did the throat slashing surely the cut would have been more like a jab to the left side of the neck,’ Angus said.

‘But still possible for the passenger to angle himself and slash from behind with negligible difference to the slash mark provided it was performed in one swift motion, left to right.’ Hurst switched her gaze from Angus to a woman bearing down on them with a tray of coffee. The hospital worker’s gaze slipped to photos strewn across the table. Hurst hastily bundled them underneath the file. The woman’s complexion took on the green hue of her hospital uniform. Stevie wondered how long she had been eavesdropping and waited for her to leave before she continued.

‘So the angle of the blade in these two scenarios can’t tell us whether he was killed in or out of the bus. What about blood spatter?’

‘We’re getting there,’ the pathologist said. ‘There was some of Notting’s blood on the bus, but also some of Robinson’s. The lab concluded it was from the impact of their heads on the windscreen. The spatter patterns are just trickles and drops and not indicative of a powerful spray.’ She removed the photo of Notting once more, this time tapping it with a neatly trimmed fingernail. ‘The neck was pulled back, making the muscle and the trachea more prominent, protecting the carotid artery but exposing the jugular. He would have died of suffocation from the severed trachea before he bled out; still, there would have been a massive gush of blood. It flowed away from the wound when he was lying down, as dictated by gravity. If you look at this photo you can see the pattern flow down either side of the neck and across the ground. The clothing along the victim’s back was also saturated, but as you can see, there is only a little on his shirt front. If he was sitting on the bus when he was killed most of the blood would be on the front of his shirt and in his lap.’

‘Would it have got on the murderer?’ Fowler asked.

‘If the carotid artery had been damaged, yes, most probably; but since only the jugular was affected here, the spray wouldn’t have been as powerful. The murderer might have been able to avoid it if he or she was careful.’

‘She,’ Angus mused. ‘The girl, Mai, was the only one conscious when the paramedics arrived. She was lying alongside her friend Lin on what was left of the floor of the bus with a badly broken leg.’

‘Could either of the girls have done the deed after the accident and crawled back into the bus?’ Stevie asked Hurst.

Hurst tapped her pen thoughtfully on the table. ‘Well, there was a considerable amount of red dust found on Mai’s clothes—much more than on the other survivor...’ She shook her head as if to silence the improbable thought. ‘But I don’t see how she could have done it. The pain from her broken femur would have been excruciating. Even if she was thrown clear of the bus during the accident, I don’t see how she could have crawled back into it after having slit Notting’s throat. And the Lin girl is out of the equation totally. She has serious head injuries. She would have lost consciousness on impact.’

Stevie drew circles through the coffee rings of the table. ‘But if Mai was determined enough...’

Fowler’s phone rang and he climbed to his feet: the interpreter was ready for her appointment. Speaking to Col and Stevie, he said, ‘Let’s go and meet this young lady. Find out how determined she might have been.’ (Image 27.1)

Image 27.1

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

The interpreter from the Thai Consulate, a straight-backed young woman in a raspberry-coloured skirt suit, met them at the nurses’ station. They were told they could stay with the patient for fifteen minutes maximum. Stevie saw the head nurse look at her watch. She envisioned a stopwatch and a starter’s gun and had to hold back from sprinting to Mai’s room.

It was decided that Stevie would conduct the interview. Their footsteps clattered down the corridor. They must sound like approaching storm-troopers to the frightened girl in the room, Stevie thought. While it was unavoidable that Fowler and Col accompany her, she would have given a month’s pay to see Mai alone.

A uniformed AFP guard jumped to his feet as they approached. Col showed his ID even though it was obvious the young man knew exactly who he was. Mai could be an important witness against the people-trafficking mob and they weren’t taking any chances over her safety.

Fowler and Col sat as far away from the bed as the small room would allow; Stevie and the interpreter, Pimjai Sarangrit, on chairs pulled up close to the bed. A plastic bag containing the green housedress sat on the floor between them.

Mai’s face was as pale as the pillow on which she lay propped and highlighted the darkness of her deep-set eyes. A cascade of eggplant-black hair framed her face. Her bandaged leg rested in a splint that looked like a medieval torture contraption, exposing bare toes, swollen and blue. It seemed the overworked nurses had not yet had time to give her a thorough wash. Streaks of red dirt were still visible between her toes. To Stevie, the sight of the dirt made Mai’s presence in the clean white bed less surreal. It served as a vivid reminder of what might have happened out there in the desert.

Stevie introduced herself through Pimjai, pulled her notebook from her bag and with Pimjai’s help carefully wrote down the girl’s complete name, Mai Prawanrum. She explained that the interview was to be recorded. Out of the corner of her eye she saw Col tap the record button of the camcorder.

When Stevie asked the girl how she was feeling, Mai’s shrug said it all: how do you think I’m feeling?

‘Can you tell me where you were going on the bus?’ Stevie asked, careful to keep her eyes on Mai and not Pimjai.

The delay between question and answer was like an overseas telephone conversation on a faulty line. ‘She says she was going to Broome,’ Pimjai said at last.

‘Why were you going to Broome, Mai?’

A quick reply.

‘To work,’ Pimjai said.

Stevie glanced at the two men in the corner of the room. ‘And what is your work?’

‘She works at...’ Pimjai hesitated while she listened to Mai, then lowered her eyes, ‘at pleasing men.’

Mai seemed to share none of Pimjai’s embarrassment. Her sloe eyes remained fixed and unwavering upon Stevie, clear proud eyes that seemed to be challenging her to react as Pimjai had done.

Stevie had no trouble keeping her expression neutral; in her job, this was just par for the course. ‘You were brought into this country illegally. Did you want to come here or were you forced?’

Mai looked at Pimjai as she answered Stevie’s question. The interpreter from the consulate sat straight in her chair, stockinged legs clamped at the knees. ‘They said they would kill her baby if she did not come to Australia with them.’

‘And where is your baby now?’

Mai turned her head away, her voice cracking with her first sign of emotion.

‘Somewhere in Australia,’ Pimjai said. ‘She doesn’t know where, but she thinks he is safe now. She saw him on the television news after he was found in the house.’

Mai pointed to Fowler as Pimjai spoke.

‘She saw that man on the news too,’ Pimjai said.

Stevie reached for Mai’s hand and noticed streaks of red dirt embedded in the creases of the girl’s fingers. She wondered what those hands had been up to, if this young girl really was capable of cold-blooded murder. Could that delicate hand have pulled a knife across a man’s throat? As she looked at Mai she attempted to smile away the thoughts. She must diffuse the suspicion in her eyes and keep the girl on side. For the time being she would stick to those least likely to cause distress: get details; clarify what they already suspected. And meanwhile, any minute now, the nurse might appear and ask them to leave.

‘Your baby is safe, and soon you will have him back.’ Stevie leaned toward the housedress in the bag on the floor. Stopped. That was another thing that would have to wait. Timing, strategy and interpretation was what it was all about, with everything to gain and everything to lose.

The temperature had risen in the overcrowded room; the antiseptic air tinted with the metallic smell of dried blood and Pilbara dirt. Unbuttoning her shirt cuffs, Stevie slid her sleeves up her arm.

Pimjai clapped her tiny hands as she translated Stevie’s words, telling the girl her baby was safe. This interpreter was showing more emotion than she should, Stevie thought; then again, so was she.

Bugger it.

When Mai’s face transformed with a joyful smile; Stevie grinned back.

‘But there are still some things we need to ask you,’ she said, wishing she didn’t have to dispel the euphoria by getting to the heart of the case. ‘I know you’re tired, but I need to know everything that happened, starting with how you came here to Australia.’

She waited patiently for the echo of her question. Mai’s reply seemed to take forever. Crossing her legs, Stevie relaxed back into her chair as if she had all the time in the world. Inside, her pulse ticked like a clock. She tried to focus on the soothing rhythms of the girl’s voice, the swooping movements of Mai’s delicate hands, small and pale except for the creases of Pilbara dirt.

Earlier she’d googled the Thai language, discovering that it contained forty consonants and twenty-four vowels—not an easy language to learn, surely. When spoken, it relied on five tones: middle, high, low, rising and falling, meaning that up to four different words might have the same spelling. Being an experienced interrogator was not enough, a different set of skills was needed to analyse this translated version of events. Tone and innuendo did not exist in the same manner as they did with an English speaker. As she continued to sit on the hard hospital chair, hearing but not understanding, she could have been listening to someone speaking from under the sea.

‘She was sold to a brothel in Bangkok when she was a small girl,’ Pimjai eventually translated. ‘She stayed there for a few years and sent money home to her parents. Then a few years later she had her baby and was sold to a different group. They said if she didn’t go overseas to work for them they would kill the baby. They said she could take him with her. But then, when she came to Australia, they took him away from her. They said it was the only way they could be guaranteed that she would work for them and not run away.’

‘What happened to her baby?’ Stevie asked as Mai flopped back against her pillows and closed her eyes. Stevie still hadn’t reached the questions at the forefront of their minds. She glanced over to Col who made hurry-up motions with his hands.

‘The man who arranged for her to be brought over,’ Pimjai said, ‘decided to keep Mai’s baby for himself because his wife could not give him a child.’

Fowler and Col straightened in their chairs; Stevie sensed them all asking the same question—Jon Pavel? But she couldn’t feed the girl the answer; for legal reasons she still had to ask the name of the man.

When Mai answered, there was no need for translation. A collective sigh of relief reached Stevie from the corner of the room.

‘Do you know what happened to Jon Pavel?’ Stevie asked.

She heard the word ‘Australian’ in Mai’s reply.

‘They killed him. They also killed his wife and the Australian man, Ralph,’ Pimjai said.

Stevie moistened her dry lips with her tongue. ‘Who killed them?’

‘Mamasan and The Crow.’ No hesitation. Mai did not seem to be frightened of recrimination.

Fowler hissed out a breath.

‘Why did they kill them?’ Stevie inched to the edge of her chair.

‘Pavel brought the girls over for the Mamasan,’ Pimjai said, ‘but he also brought others of his own, using the Mamasan’s network of contacts, even the Mamasan’s money—he lied to her about what he paid for them. He kept them at his house while he waited to sell them on. Mai was one of the ones he organised to keep for himself. Then the Mamasan found out. His excuse was that he didn’t think she’d mind because she had never been interested in girls who’d given birth...’ The pale skin of Pimjai’s neck flushed. ‘She says the clients don’t like them as much...’

These girls were investment commodities, Stevie reflected, items to be bought, sold, stolen and devalued.

‘Mamasan warned him to stop and set his house on fire to make him listen. He gave Mai back to the Mamasan, thinking that would be enough to please her. But he and the Australian, Ralph Hardegan, continued to bring the girls in. They were making so much money it was like a drug to them, they couldn’t stop. When the Mamasan found out, she killed Pavel, his wife and the man Ralph as an example to anyone else who tried to cross her.’

Just as they had suspected, Pavel and Hardegan had paid the price for undercutting the Mamasan. You take my girls and I take you: skin for skin.

‘We haven’t been able to locate Jon Pavel’s body yet,’ Stevie said.

Pimjai listened to Mai. ‘Mai saw them kill him,’ she said with a shudder. ‘They tortured him, burned off his skin, and then took his body out to sea in a boat, weighted it down and dumped it over the side.’

No wonder they hadn’t found the body. Stevie decided not to press for details of the torture, not yet, even though they would have to be documented later. Looking from one pale face to the other, she wondered how much more either girl could take.

Col beckoned her over and handed her a computer image of an aged Jennifer Granger, a picture Stevie had not yet seen. Pulling a photo of the young Granger from her jeans pocket she compared the peachy round face, wide innocent eyes and gap-toothed smile to the woman in the age-enhanced picture. Could the cherub really have turned into this dugong-faced creature? Stevie’s inability to spot a single shared feature made her sceptical of the picture’s value. She knew the age-enhancing process involved a mixture of science, art, facial growth data and heredity, and had often been invaluable in the hunt for long-term missing persons. But she had trouble coming to terms with the idea that an artist or scientist could predict the influence of lifestyle and experience on a face, when he had no idea what those influences might be. In this instance, he certainly seemed to have expected the worst.

She made eye contact with Col. ‘Surely this doesn’t take plastic surgery into account? You said she’d had various makeovers.’

He shrugged—God only knows—and urged her back to Mai with a firm nod of his head.

‘Do you know who this woman is, Mai?’ she asked, forsaking her chair to perch on the edge of the bed.

Mai’s head dipped as she examined the picture of the older Granger, a veil of hair falling over her face, hiding it. Pimjai took a peep at the picture too and said something to Mai who returned a single word answer. Pimjai responded with an uneasy laugh.

‘Well, Pimjai?’ Stevie asked.

‘She said the woman is very ugly.’

Stevie blew out a breath of impatience. ‘Yes, but does she recognise her?’

‘Wait, give her longer.’

Shit, how long does she need? Stevie fidgeted with her shirtsleeves while she waited, trying to roll them into neat folds of military precision, ending up making uncomfortable knots at her elbows instead. Her gaze dropped once more to the picture Mai held in her hand.

And then her breath caught.

She bent over the picture and examined it again, her cheek almost touching Mai’s. She knew that face, she was certain, there was something about the mouth. Must be a known Madam, she reasoned, familiar from one of the reams of mugshots imprinted on her mind. She would send this composite to her colleagues in Sex Crimes and see if it rang any bells.

Mai took a bolstering breath. ‘Mamasan.’ The single word needed no translation. Col pointed a told-you-so finger at Stevie before indicating for her to continue with the questions. ‘But now she looks different,’ Pimjai added after listening again to Mai.

‘Different, how?’ Stevie asked.

‘Mai, do you know an old woman called Mrs Hardegan?’ Fowler asked simultaneously. Stevie could have murdered him.

‘No!’ Mai gasped in English, having obviously recognised the name. Her dark eyes flitted in panic away from Stevie’s. She pulled the sheet over her head and lay as inert as a body under a shroud.

‘She’s an old woman who lives next door to the Pavels.’ May as well finish what Fowler had started, Stevie decided. ‘Mai, you must know who she is.’

Mai shook her head vigorously under the sheet, making a low, keening sound. Stevie glanced toward Fowler, who looked on with exasperation.

Pimjai turned on Stevie. ‘This must end now—you, your questions, you are upsetting her.’ Before Stevie could react, Pimjai gave the nurses’ call button three sharp jabs—emergency—then let rip with a rapid stream of Thai.

‘Hey, wait on a minute...’ Stevie began.

‘No more talk,’ Pimjai said, ‘If she has to speak to you again it must be with a lawyer.’

Stevie plucked at the sleeve of Pimjai’s Audrey Hepburn suit and shook her head in desperation. ‘Pimjai, Mai’s not in trouble, she’s a witness only—you’re hardly being professional about this...’

A nurse dashed into the room and pulled up short when she realised it wasn’t an emergency. Despite Fowler jabbing his thumb accusingly at Pimjai, they were told they had to leave.

‘Shit,’ Fowler said as they stepped into the passageway, his lower lip jutting with disappointment. ‘What an obstructive little cow, she doesn’t miss much does she? Talk about the sisterhood. We’re going to have to lodge a complaint against that one.’