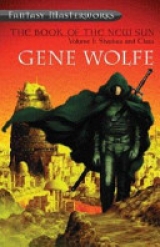

Текст книги "Shadow and Claw"

Автор книги: Джин Родман Вулф

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Dr. Tabs said, "Come on, both of you. If we're to eat and talk and get anything done today – why, we must be at it. Much to say and much to do." Baldanders spat into the corner.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN – THE RAG SHOP

It was on that walk through the streets of still slumbering Nessus that my grief, which was to obsess me so often, first gripped me with all its force. When I had been imprisoned in our oubliette, the enormity of what I had done, and the enormity of the redress I felt sure I would make soon under Master Gurloes's hands, had dulled it. The day before, when I had swung down the Water Way, the joy of freedom and the poignancy of exile had driven it away. Now it seemed to me that there was no fact in all the world beyond the fact of Thecla's death. Each patch of darkness among the shadows reminded me of her hair; every glint of white recalled her skin. I could hardly restrain myself from rushing back to the Citadel to see if she might not still be sitting in her cell, reading by the light of the silver lamp.

We found a cafe whose tables were set along the margin of the street. It was still sufficiently early that there was very little traffic. A dead man (he had, I think, been suffocated with a lambrequin, there being those who practice that art) lay at the corner. Dr. Talos went through his pockets, but came back with empty hands.

"Now then," he said. "We must think. We must contrive a plan." A waitress brought mugs of mocha, and Baldanders pushed one toward him. He stirred it with his forefinger.

"Friend Severian, perhaps I should elucidate our situation. Baldanders – he is my only patient – and I hail from the region about Lake Diuturna. Our home burned, and needing a trifle of money to set it right again we decided to venture abroad. My friend is a man of amazing strength. I assemble a crowd, he breaks some timbers and lifts ten men at once, and I sell my cures. Little enough, you will say. But there's more. I've a play, and we've assembled properties. When the situation is favorable, he and I enact certain scenes and even invite the participation of some of the audience. Now, friend, you say you are going north, and from your bed last night I take it you are not in funds. May I propose a joint venture?"

Baldanders, who appeared to have understood only the first part of his companion's speech, said slowly, "It is not entirely destroyed. The walls are stone, very thick. Some of the vaults escaped."

"Quite correct. We plan to restore the dear old place. But see our dilemma we're now halfway on the return leg of our tour, and our accumulated capital is still far from sufficient. What I propose-"

The waitress, a thin young woman with straggling hair, came carrying a bowl of gruel for Baldanders, bread and fruit for me, and a pastry for Dr. Talos. "What an attractive girl!" he said.

She smiled at him.

"Can you sit down? We seem to be your only customers." After glancing in the direction of the kitchen, she shrugged and pulled over a chair.

"You might enjoy a bit of this – I'll be too busy talking to eat such a dry concoction. And a sip of mocha, if you don't object to drinking after me." She said, "You'd think he'd let us eat for nothing, wouldn't you? But he won't. Charges everything at full price."

"Ah! You're not the owner's daughter, then. I feared you were. Or his wife. How can he have allowed such a blossom to flourish unplucked?"

"I've only worked here about a month. The money they leave on the table's all I get. Take you three, now. If you don't give me anything, I will have served you for nothing."

"Quite so, quite so! But what about this? What if we attempt to render you a rich gift, and you refuse it?" Dr. Talos leaned toward her as he said this, and it struck me that his face was not only that of a fox (a comparison that was perhaps too easy to make because his bristling reddish eyebrows and sharp nose suggested it at once) but that of a stuffed fox. I have heard those who dig for their livelihood say there is no land anywhere in which they can trench without turning up the shards of the past. No matter where the spade turns the soil, it uncovers broken pavements and corroding metal; and scholars write that the kind of sand that artists call polychrome (because flecks of every color are mixed with its whiteness) is actually not sand at all, but the glass of the past, now pounded to powder by aeons of tumbling in the clamorous sea. If there are layers of reality beneath the reality we see, even as there are layers of history beneath the ground we walk upon, then in one of those more profound realities, Dr. Tabs's face was a fox's mask on a wall, and I marveled to see it turn and bend now toward the woman, achieving by those motions, which made expression and thought appear to play across it with the shadows of the nose and brows, an amazing and realistic appearance of vivacity. "Would you refuse it?" he asked again, and I shook myself as though waking.

"What do you mean?" the woman wanted to know. "One of you is a carnifex. Are you talking about the gift of death? The Autarch, whose pores outshine the stars themselves, protects the lives of his subjects."

"The gift of death? Oh, no!" Dr. Talos laughed. "No, my dear, you've had that all your life. So has he. We wouldn't pretend to give you what is already yours. The gift we offer is beauty, with the fame and wealth that derive from it."

"If you're selling something, I haven't got any money."

"Selling? Not at all! Quite the contrary, we are offering you new employment. I am a thaumaturge, and these optimates are actors. Have you never wanted to go on the stage?"

"I thought you looked funny, the three of you."

"We stand in need of an ingenue. You may claim the position, if you wish. But you must come with us now – we've no time to waste, and we won't come this way again."

"Becoming an actress won't make me beautiful."

"I will make you beautiful because we require you as an actress. It is one of my powers." He stood up. "Now or not at all. Will you come?" The waitress rose too, still looking at his face. "I have to go to my room . .

."

"What do you own but dross? I must cast the glamour and teach you your lines, all in a day. I will not wait."

"Give me the money for your breakfasts, and I'll tell him I'm leaving."

"Nonsense! As a member of our company, you must assist in conserving the funds we will require for your costumes. Not to mention that you ate my pastry. Pay for it yourself."

For an instant she hesitated. Baldanders said, "You may trust him. The doctor has his own way of looking at the world, but he lies less than people believe." The deep, slow voice seemed to reassure her. "All right," she said, "I'll go." In a few moments, the four of us were several streets away, walking past shops that were still for the most part shuttered. When we had gone some distance, Dr. Talos announced, "And now, my dear friends, we must separate. I will devote my time to the enhancement of this sylph. Baldanders, you must get our collapsing proscenium and the other properties from the inn where you and Severian spent the night – I trust that will present no difficulties. Severian, we will perform, I think, at Ctesiphon's Cross. Do you know the spot?" I nodded, though I had no notion of where it might be. The truth was that I had no intention of rejoining them.

Now, as Dr. Talos quick-stepped away with the waitress trotting behind him, I found myself alone with Baldanders on the deserted street. Anxious that he leave too, I asked him where he meant to go. It was more like talking to a monument than speaking with a man.

"There is a park near the river where one may sleep by day, though not by night. When it is nearly dark, I will awaken and collect our belongings."

"I'm afraid I'm not sleepy. I'm going to look around the city."

"I will see you then, at Ctesiphon's Cross."

For some reason I felt he knew what was in my mind. "Yes," I said. "Of course." His eyes were dull as an ox's as he turned away to lumber with long steps toward Gyoll. Since Baldanders's park lay east and Dr. Talos had taken the waitress west, I resolved to walk north and so continue my journey toward Thrax, the City of Windowless Rooms.

Meanwhile, Nessus, the City Imperishable (the city in which I had lived all my life, though I had seen so little of it), lay all about me. Along a wide, flint-paved avenue I walked, not knowing or caring whether it was a side street or the principal one of the quarter. There were raised paths for pedestrians at either side, and a third in the center, where it served to divide the northbound traffic from the southbound.

To the left and right, buildings seemed to spring from the ground like grain too closely planted, shouldering one another for a place; and what buildings they were -nothing so large as the Great Keep and nothing so old; none, I think, with walls like the metal walls of our tower, five paces through; yet the Citadel had nothing to compare with them in color or originality of conception, nothing so novel and fantastic as each of these structures was, though each stood among a hundred others. As is the fashion in some parts of the city, most of these buildings had shops in their lower levels, though they had not been built for the shops but as guildhalls, basilicas, arenas, conservatories, treasuries, oratories, artellos, asylums, manufacturies, conventicles, hospices, lazarets, mills, refectories, deadhouses, abattoirs, and playhouses. Their architecture reflected these functions, and a thousand conflicting tastes. Turrets and minarets bristled; lanterns, domes, and rotundas soothed; flights of steps as steep as ladders ascended sheer walls; and balconies wrapped facades and sheltered them in the par-terre privacies of citrons and pomegranates. I was wondering at these hanging gardens amid the forest of pink and white marble, red sardonyx, blue-gray, and cream, and black bricks, and green and yellow and tyrian tiles, when the sight of a lansquenet guarding the entrance to a casern reminded me of the promise I had made the officer of the peltasts the night before. Since I had little money and was well aware that I would require the warmth of my guild cloak by night, the best plan seemed to be to buy a voluminous mantle of some cheap stuff that could be worn over it. Shops were opening, but those that sold clothing all appeared to sell what would not fit my purpose, and at prices greater than I could afford.

The idea of working at my profession before I reached Thrax had not yet occurred to me; if it had, I would have dismissed it, supposing that there would be so little call for a torturer's services that it would be impractical for me to seek out those who required them. I believed, in short, that the three asimis, and the orichalks and aes in my pocket would have to carry me all the way to Thrax; and I had no idea of the size of the rewards that would be proffered me. Thus I stared at balmacaans and surtouts, dolmans and jerkins of paduasoy, matelasse, and a hundred other costly fabrics without ever going into the places that displayed them, or even stopping to examine them.

Soon my attention was seduced by other goods. Though I knew nothing of it at the time, thousands of mercenanes were outfitting themselves for the summer campaign. There were bright military capes and saddle blankets, saddles with armored pommels to protect the loins, red forage caps, long-shafted khetens, fans of silver foil for signaling, bows curved and recurved for use by cavalry, arrows in matched sets of ten and twenty, bow cases of boiled leather decorated with gilt studs and mother-of-pearl, and archers' guards to protect the left wrist from the bowstring. When I saw all these, I remembered what Master Palaemon had said before my masking about following the drum; and although I had held the matrosses of the Citadel in some contempt, I seemed to hear the long rattle of the call to parade, and the bright challenge the trumpets sent from the battlements.

Just when I had been wholly distracted from my search, a slender woman of twenty or a little more came out of one of the dark shops to unfasten the gratings. She wore a pavonine brocade gown of amazing richness and raggedness, and as I watched her, the sun touched a rent just below her waist, turning the skin there to palest gold.

I cannot explain the desire I felt for her, then and afterward. Of the many women I have known, she was, perhaps, the least beautiful – less graceful than her I have loved most, less voluptuous than another, less reginal far than Thecla. She was of average height, with a short nose, wide cheekbones, and the elongated brown eyes that often accompany them. I saw her lift the grating, and I loved her with a love that was deadly and yet not serious. Of course I went to her. I could no more have resisted her than I could have resisted the blind greed of Urth if I had tumbled over a cliff. I did not know what to say to her, and I was terrified that she would recoil in horror at the sight of my sword and fuligin cloak. But she smiled and actually seemed to admire my appearance. After a moment, when I said nothing, she asked what I wanted; and I asked if she knew where I might buy a mantle.

"Are you sure you need one?" Her voice was deeper than I had expected. "You've such a beautiful cloak now. May I touch it?"

"Please. If you wish to."

She took up the edge and rubbed the fabric gently between her palms. "I've never seen such a black – so dark you can't see folds in it. It makes my hand look as though it's disappeared. And that sword. Is that an opal?"

"Would you like to examine that too?"

"No, no. Not at all. But if you really want a mantle . . ." She gestured toward the window, and I saw that it was filled with articles of worn clothing of every kind, jelabs, capotes, smocks, cymars, and so on. "Very inexpensive. Really reasonable. If you'll just go in, I'm sure you'll find what you want." I entered through a jingling door, but the young woman did not (as I had so much hoped she would) follow me inside.

The interior was dim, yet as soon as I looked about I thought I understood why the woman had not been disturbed by my appearance. The man behind the counter was more frightening than any torturer. His face was a skeleton's or nearly so, a face with dark pits for eyes, shrunken cheeks, and a lipless mouth. If it had not moved and spoken, I would not have believed he was a living man at all, but a corpse left erect behind the counter in fulfilment of the morbid wish of some past owner.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN – THE CHALLENGE

Yet it did move, turning to look at me as I came in; and it did speak. "Wery fine. Yes, very fine. Your cloak, optimate – may I see it?" I walked across a floor of worn and uneven tiles to him. A slash of red sunshine alive with swarming dust stood stiff as a blade between us.

"Your garment, optimate." I caught up my cloak and extended my left hand, and he touched the fabric much as the young woman had outside. "Yes, very fine. Soft. Wool-like, yet softer, much softer. A blend of linen and vicuna? And wonderful color. A torturer's vesture. One doubts the real ones were half so fine, but who can argue with a textile like that?" He ducked beneath his counter and emerged with a handful of rags. "Might I examine the sword? I'll be extremely careful, I promise you."

I unsheathed Ternunus Est and laid her on the rags. He bent over her, neither touching her nor speaking. By that time my eyes had become accustomed to the dimness of the shop, and I noticed a narrow black ribbon that stretched forward a finger's width from the hair above his ears. "You are wearing a mask," I said.

"Three chrisos. For the sword. Another for the cloak."

"I didn't come here to sell," I told him. "Take it off."

"If you like. All right, four chrisos for the sword." He lifted his hands and the death's-head fell into them. His real face, flatcheeked and tanned, was remarkably like that of the young woman I had seen outside.

"I want to buy a mantle."

"Five chrisos for it. That's positively my last offer. You'll have to give me a day to raise the money."

"I told you, this sword is not for sale." I picked up Terminus Est and resheathed her.

"Six." Reaching across the counter, he took me by the arm. 'That's more than it's worth. Listen, it's your last chance. I mean it. Six."

"I came in to buy a mantle. Your sister, as I would assume she was, said you would have one at a reasonable price."

He sighed. "All right, I'll sell you a mantle. Will you tell me first where you got that sword?"

"It was given me by a master of our guild." I saw an expression I could not quite identify flicker across his face, and I asked, "You don't believe me?"

"I do believe you, that's the trouble. Just what are you?"

"A journeyman of the torturers. We don't often get to this side of the river, or come this far north. But are you really so surprised?" He nodded. "It's like encountering a psychopomp. Can I ask why you're in this quarter of the city?"

"You may, but it's the last question I'm going to answer. I'm on my way to Thrax, to take up an assignment there."

"Thank you," he said. "I won't pry any more. I don't have to, really. Now since you'll want to surprise your friends when you take off your mantle – am I right?

– it ought to be of some color that will contrast with your vesture. White might be good, but it's a rather dramatic color itself, and terribly hard to keep clean. What about a dull brown?"

"The ribbons that held your mask," I said. "They're still there." He was dragging down boxes from behind his counter and did not reply. After a moment or two we were interrupted by the tinkling of the bell above the door. The new customer was a youth whose face was hidden in an inlaid close helmet, of which downcurving and intertwined horns formed the visor. He wore armor of lacquered leather; a golden chimera with the blank, staring face of a madwoman fluttered on his breastplate.

"Yes, hipparch." The shopkeeper dropped his boxes to make a servile bow. "How may I assist you?"

A gauntleted hand reached toward me, the fingers pinched as though to give me a coin.

"Take it," the shopkeeper said in a frightened whisper. "Whatever it is." I extended my own hand, and received a shining black seed the size of a raisin. I heard the shopkeeper gasp; the armored figure turned and went out. When he was gone, I laid the seed on the counter. The shopkeeper squeaked,

"Don't try to pass it to me!" and backed away.

"What is it?"

"You don't know? The stone of the avern. What have you done to offend an officer of the Household Troops?"

"Nothing. Why did he give me this?"

"You've been challenged. You're called out."

"To monomachy? Impossible. I'm not of the contending class." His shrug was more eloquent than words. "You'll have to fight, or they'll have you assassinated. The only question is whether you've really offended the hipparch, or if there's some highly placed official of the House Absolute behind this."

As clearly as I saw the shopkeeper, I saw Vodalus in the necropolis standing his ground against the three volunteer guards; and though all prudence told me to toss aside the avern stone and flee the city, I could not do it. Someone perhaps the Autarch himself or shadowy Father Inire – had learned the truth about Thecla's death, and now sought to destroy me without disgracing the guild. Very well, I would fight. If I were victorious he might reconsider; if I were killed, that would be no more than just. Still thinking of Vodalus's slender blade, I said, "The only sword I understand is this one."

"You won't engage with swords – in fact, it would be best if you left that with me."

"Absolutely not."

He sighed again. "I see you know nothing about these matters, yet you are going to fight for your life at twilight. Very well, you are my customer, and I've never yet abandoned a customer. You wanted a mantle. Here." He strode to the back of his shop and came forward carrying a garment the color of dead leaves.

"Try this one. It will be four orichalks if it fits." A mantle so large and loose could not but fit unless it was grossly short or long. The price seemed excessive, but I paid, and in donning the mantle took one step further toward becoming the actor that day seemed to wish to force me to become. Indeed, I was already taking part in more dramas than I realized.

"Now then," the shopkeeper said, "I must stay here to look after things, but I'll send my sister to help you get your avern. She has often gone to the Sanguinary Field, so perhaps she can also teach you the rudiments of combat with it."

"Did someone speak of me?" The young woman I had met at the front of the shop now came from one of the dark storerooms at its rear. With her upturned nose and strangely tilted eyes, she looked so much like her brother I felt sure they were twins, but the slender figure and delicate features that seemed incongruent in him were compelling in her. Her brother must have explained what had befallen me. I do not know, because I did not hear it. I was looking only at her. Now I begin again. It has been a long time (twice I have heard the guard changed outside my study door) since I wrote the lines you read only a moment before. I am not certain it is right to record these scenes, which perhaps are important only to me, in so much detail. I might easily have condensed everything: I saw a shop and went in; I was challenged by an officer of the Septentrions; the shopkeeper sent his sister to help me pluck the poisoned flower. I have spent weary days in reading the histories of my predecessors, and they consist of little but such accounts. For example, of Ymar:

Disguising himself, he ventured into the countryside, where he spied a muni meditating beneath a plane tree. The Autarch joined him and sat with his back to the trunk until Urth had begun to spurn the sun. Troopers bearing an oriflamme galloped past, a merchant drove a mule staggering under gold, a beautiful woman rode the shoulders of eunuchs, and at last a dog trotted through the dust. Ymar rose and followed the dog, laughing.

Supposing this anecdote to be true, how easy it is to explain: the Autarch had demonstrated that he chose his active life by an act of will, and not because of the seductions of the world.

But Thecla had had many teachers, each of whom would explain the same fact in a different way. Here, then, a second teacher might say that the Autarch was proof against those things that attract common men, but powerless to control his love of the hunt.

And a third, that the Autarch wished to show his contempt for the muni, who had remained silent when he might have poured forth enlightenment and received more. That he could not do by leaving when there was none to share the road, since solitude has great attractions for the wise. Nor could he when the soldiers passed, nor the merchant with his wealth, nor the woman, for unenlightened men desire all those things, and the muni would have thought him one more such man. And a fourth, that the Autarch accompanied the dog because it went forth alone, the soldiers having other soldiers, the merchant his mule and the mule his merchant, and the woman her slaves; while the muni did not go forth. Yet why did Ymar laugh? Who shall say? Did the merchant follow the soldiers to buy their booty? Did the woman follow the merchant to sell her kisses and her loins? Was the dog of the hunting kind, or such a short-limbed one as women keep to bark lest someone fondle them while they sleep? Who now shall say? Ymar is dead, and such memories of his as lived for a time in the blood of his successors are long faded.

So mine in time shall fade too. Of this I feel sure: not one of the explanations for the behavior of Ymar was correct. The truth, whatever it may have been, was simpler and more subtle. Of me it might be asked why I accepted the shopkeeper's sister as my cornpanion – I who in all my life had had no true companion. And who, reading only of "the shopkeeper's sister," would understand why I remained with her after what is, at this point in my own story, about to happen? No one, surely.

I have said that I cannot explain my desire for her, and it is true. I loved her with a love thirsty and desperate. I felt that we two might commit some act so atrocious that the world, seeing us, would find it irresistible. No intellect is needed to see those figures who wait beyond the void of death every child is aware of them, blazing with glories dark or bright, wrapped in authority older than the universe. They are the stuff of our earliest dreams, as of our dying visions. Rightly we feel our lives guided by them, and rightly too we feel how little we matter to them, the builders of the unimaginable, the fighters of wars beyond the totality of existence.

The difficulty lies in learning that we ourselves encompass forces equally great. We say, "I will," and "I will not," and imagine ourselves (though we obey the orders of some prosaic person every day) our own masters, when the truth is that our masters are sleeping. One wakes within us and we are ridden like beasts, though the rider is but some hitherto unguessed part of ourselves. Perhaps, indeed, that is the explanation of the story of Ymar. Who can say?

However that may be, I let the shopkeeper's sister help me adjust the mantle. It could be drawn tightly about the neck, and when it was worn so, my fuligin guild cloak was invisible beneath it. Still without revealing myself, I could reach through the front or through slits at the sides. I unfastened Terminus Est from her baldric and carried her like a staff for as long as I wore that mantIe, and because her sheath covered most of her guard and was tipped with dark iron, many of the people who saw me no doubt thought it was one.

It was the only time in my life when I have covered the habit of the guild with a disguise. I have heard it said that one always feels a fool in them, whether they succeed or not, and surely I felt a fool in that one. And yet it was hardly a disguise at all. Those wide, old-fashioned mantles originated with shepherds (who wear them still), and were passed from them to the military in the days when the fighting with the Ascians took place here in the cool south. From the army they were taken up by religious pilgrims, who no doubt found a garment that could be converted into a more-or-less-satisfactory little tent very practical. The decline of religion has no doubt done much to extinguish them in Nessus, where I never saw any other than the one I wore myself. If I had known more about them when I put on mine in the rag shop, I would have bought a soft, wide-brimmed hat to go with it; but I did not, and the shopkeeper's sister told me I looked a good palmer. No doubt she said it with that twinkle of mockery with which she said everything else, but I was concerned with my appearance and failed to notice it. I told her and her brother that I wished I knew more of religion.

Both smiled, and the brother said, "If you mention it first, no one will want to talk about it. Besides, you can get the reputation of being a good fellow by wearing that and not talking about it. When you meet someone you don't want to talk to at all, beg alms."

So I became, in appearance at least, a pilgrim bound for some vague northern shrine. Have I said that time turns our lies into truths?