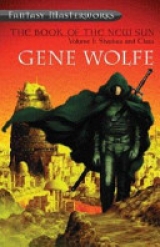

Текст книги "Shadow and Claw"

Автор книги: Джин Родман Вулф

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN – FOOL'S FIRE

I was ringed by faces. Two women took Jonas from me, and promising to care for him carried him away. The rest began to ply me with questions. What was my name? What clothes were those I wore?

Where had I come from? Did I know such a one, or such a one, or such a one? Had I ever been to this town or that? Was I of the House Absolute? Of Nessus? From the east bank of Gyoll or the west? What quarter? Did the Autarch still live? What of Father Inire? Who was archon in the city? How went the war? Had I news of so-and-so, a commander? Of so-and-so, a trooper? Of so-and-so, a chiliarch?

Could I sing, recite, play an instrument? As may be imagined, in such a welter of inquiries I was able to answer almost none. When the first flurry was spent, an old, gray-bearded man and a woman who seemed almost equally old silenced the others and drove them away. Their method, which would surely have succeeded nowhere but here, was to clap each by the shoulder, point to the most remote part of the room, and say distinctly, "Plenty of time." Gradually the others fell silent and walked to what seemed the limits of hearing, until at last the low room was as still as it had been when the doors opened.

"I am Lomer," the old man said. He cleared his throat noisily. "This is Nicarete." I told him my name, and Jonas's.

The old woman must have heard the concern in my voice. "He will be safe, rest assured. Those girls will treat him as well as they can, in the hope that he'll soon be able to talk to them." She laughed, and something in the way she threw back her well-shaped head told me she had once been beautiful. I began to question them in my turn, but the old man interrupted me. "Come with us," he said, "to our corner. We will be able to sit at ease there, and I can offer you a cup of water." As soon as he pronounced the word, I realized that I was terribly thirsty. He led us behind the rag screen nearest the doors and poured water for me from an earthenware jug into a delicate porcelain cup. There were cushions there, and a little table not more than a span high.

"Question for question," he said. "That's the old rule. We have told you our names and you have told us yours, and so we begin again. Why were you taken?" I explained that I did not know, unless it were merely for violating the grounds.

Lomer nodded. His skin was of that pale color peculiar to those who never see the sun; with his straggling beard and uneven teeth, he would have been repulsive in any other setting; but he belonged here as much as the half-obliterated tiles of the floor did. "I am here by the malice of the Chatelaine Leocadia. I was seneschal to her rival the Chatelaine Nympha, and when she brought me here to the House Absolute with her in order that we might review the accounts of the estate while she attended the rites of the philomath Phocas, the Chatelaine Leocadia entrapped me by the aid of Sancha, who—" The old woman, Nicarete, interrupted him. "Look!" she exclaimed. "He knows her." And so I did. A chamber of pink and ivory had risen in my mind, a room of which two walls were clear glass exquisitely framed. Fires burned there on marble hearths, dimmed by the sunbeams streaming through the glass but filling the room with a dry heat and the odor of sandalwood. An old woman wrapped in many shawls sat in a chair that was like a throne; a decanter of cut crystal and several brown phials stood on an inlaid table at her side.

"An elderly woman with a hooked nose," I said. "The Dowager of Fors."

"You do know her then." Lomer's head nodded slowly, as though it were answering the question put by its own mouth. "You are the first in many years."

"Let us say that I remember her."

"Yes." The old man nodded. "They say she is dead now. But in my day she was a fine, healthy young woman. The Chatelaine Leocadia persuaded her to it, then caused us to be discovered, as Sancha knew she would. She was but fourteen, and no crime was charged to her. We had done nothing in any case; she had only begun to undress me."

I said, "You must have been quite a young man yourself."

He did not answer, so Nicarete replied for him. "He was twenty-eight."

"And you," I asked. "Why are you here?"

"I am a volunteer."

I looked at her in some surprise.

"Someone must make amends for the evil of Urth, or the New Sun will never come. And someone must call attention to this place and the others like it. I am of an armiger family that may yet remember me, and so the guards must be careful of me, and of all the others while I remain here."

"Do you mean that you can leave, and will not?"

"No," she said, and shook her head. Her hair was white, but she wore it flowing about her shoulders as young women do. "I will leave, but only on my own terms, which are that all those who have been here so long that they have forgotten their crimes be set free as well." I remembered the kitchen knife I had stolen for Thecla, and the ribbon of crimson that had crept from under the door of her cell in our oubliette, and I said, "Is it true that prisoners really forget their crimes here?"

Lomer looked up at that. "Unfair! Question for question—that's the rule, the old rule. We still keep the old rules here. We're the last of the old crop, Nicarete and me, but while we last, the old rules still stand. Question for question. Have you friends who may strive for your release?" Dorcas would, surely, if she knew where I was. Dr. Talos was as unpredictable as the figures seen in clouds, and for that very reason might seek to have me freed, though he had no real motive for doing so. Most importantly, perhaps, I was Vodalus's messenger, and Vodalus had at least one agent in the House Absolute—him to whom I was supposed to deliver his message. I had tried to cast away the steel twice while Jonas and I were riding north, but had found that I could not; the alzabo, it seemed, had laid yet another spell upon my mind. Now I was glad of that.

"Have you friends? Relations? If you have, you may be able to do something for the rest of us."

"Friends, possibly," I said. "They may try to help me if they ever learn what has happened to me. Is it likely they may succeed?"

In that way we talked for a long time; if I were to write it all here, there would be no end to this history. In that room, there is nothing to do but talk and play a few simple games, and the prisoners do those things until all the savor has gone out of them, and they are left like gristle a starving man has chewed all day. In many respects, these prisoners are better off than the clients beneath our own tower; by day they have no fear of pain, and none is alone. But because most of them have been there so long, and few of our clients had been long confirmed, ours were, for the most part, filled with hope, while those in the House Absolute are despairing.

After what must have been ten watches or more, the glowing lamps in the ceiling began to fade, and I told Lomer and Nicarete I could remain awake no longer. They led me to a spot far from the door, where it was very dark, and explained that it would be mine until one of the other prisoners died and I succeeded to a better position.

As they left, I heard Nicarete say, "Will they come tonight?" Lomer made some reply, but I could not say what that reply was, and I was too fatigued to ask. My feet told me there was a thin pallet on the floor; I sat down and had begun to stretch myself full-length when my hand touched a living body. Jonas's voice said, "You needn't jerk back. It's only me."

"Why didn't you say something? I saw you walking about, but I couldn't break away from the two old people. Why didn't you come over?"

"I didn't say anything because I was thinking. And I didn't come over because I couldn't break away from the women who had me, at first. Afterward, those people couldn't break away from me. Severian, I must escape from here."

"Everyone wants to, I suppose," I told him. "Certainly I do."

"But I must." His thin, hard hand—his left hand of flesh—gripped mine. "If I don't, I will kill myself or lose my reason. I've been your friend, haven't I?" His voice dropped to the faintest of whispers. "Will the talisman you carry . . . the blue gem . . . set us free? I know the praetorians didn't find it; I watched while they searched you."

"I don't want to take it out," I said. "It gleams so in the dark."

"I'll turn one of these mats on its side and hold it to shield us." I waited until I could feel the pallet in position, then drew out the Claw. Its light was so faint I might have shaded it with my hand.

"Is it dying?" Jonas asked.

"No, it's often like this. But when it is active—when it transmuted the water in our carafe and when it awed the man-apes—it shines brightly. If it can procure our escape at all, I don't believe it will do so now."

"We must take it to the door. It might spring the lock." His voice was shaking.

"Later, when the others are all asleep. I'll free them if we can get free ourselves; but if the door doesn't open—and I don't think it will—I don't want them to know I have the Claw. Now tell me why you must escape at once."

"While you were talking to the old people I was being questioned by a whole family," Jonas began.

"There were several old women, a man of about fifty, another about thirty, three other women, and a flock of children. They had carried me to their own little niche in the wall, you see, and the other prisoners couldn't come there unless they were invited, which they weren't. I expected that they'd ask me about friends on the outside, or politics, or the fighting in the mountains. Instead I seemed to be only a kind of amusement for them. They wanted to hear about the river, and where I had been, and how many people dressed the way I did. And the food outside—there were a great many questions about food, some of them quite ludicrous. Had I ever seen butchering? And did the animals plead for their lives? And was it true that the ones who make sugar carried poisoned swords and would fight to defend it?"

"They had never seen bees, and seemed to think they were about the size of rabbits."

"After a time I began to ask questions of my own and found that none of them, not even the oldest woman, had ever been free. Men and women are put into this room alike, it seems, and in the course of nature they produce children. And though some are taken away, most remain here throughout their lives. They have no possessions and no hope of release. Actually, they don't know what freedom is, and although the older man and one girl told me seriously that they would like to go outside, I don't think they meant to stay. The old women are seventh-generation prisoners, so they said—but one let it slip that her mother had been a seventh-generation prisoner as well."

"They are remarkable people in some respects. Externally they have been shaped completely by this place where they have spent all their lives. Yet beneath that are . . ." Jonas paused, and I could feel the silence pressing in all about us. "Family memories, I suppose you could call them. Traditions from the outside world that have been handed down to them, generation to generation, from the original prisoners from whom they are descended. They don't know what some of the words mean any longer, but they cling to the traditions, to the stories, because those are all they have; the stories and their names." He fell silent. I had thrust the tiny spark of the Claw back into my boot, and we were in perfect darkness. His labored breathing was like the pumping of the bellows at a forge.

"I asked them the name of the first prisoner, the most remote from whom they counted their descent. It was Kimleesoong . . . Have you heard that name?" I told him I had not.

"Or anything like it? Suppose it were three words."

"No, nothing like that," I said. "Most of the people I have known have had one-word names like you, unless a part of the name was a title, or a nickname of some sort that had been attached to it because there were too many Bolcans or Altos or whatever."

"You told me once that you thought I had an unusual name. Kim Lee Soong would have been a very common kind of name when I was . . . a boy. A common name in places now sunk beneath the sea. Have you ever heard of my ship, Severian? She was the Fortunate Cloud."

"A gambling ship? No, but—"

My eye was caught by a gleam of greenish light so faint that even in that darkness it was scarcely visible. At once there came a murmur of voices echoing and reechoing throughout the wide low, crooked room. I heard Jonas scrambling to his feet. I did the same, but I was no sooner up than I was blinded by a flash of blue fire. The pain was as severe as I have ever felt; it seemed as though my face were being torn away. I would have fallen if it had not been for the wall. Somewhere farther off the blue fire flashed again, and a woman cried out.

Jonas was cursing—at least, the tone of his voice told me he was cursing, though the words came in tongues unknown to me. I heard his boots on the floor. There was another flash, and I recognized the lightning—like sparks I had seen the day Master Gurloes, Roche, and I administered the revolutionary to Thecla. No doubt Jonas screamed as I had, but by that time there was such bedlam I could not distinguish his voice.

The greenish light grew stronger, and while I watched, still more than half paralyzed with pain and wracked by as much fear as I can recall ever having experienced, it gathered itself into a monstrous face that glared at me with saucer eyes, then quickly faded to mere dark.

All this was more terrifying than my pen could ever convey, though I were to slave over this part of my account forever. It was the fear of blindness as well as of pain, but we were all, for all that mattered, already blind. There was no light, and we could make none. There was not one of us who could light a candle or so much as strike fire to tinder. All around that cavernous room, voices screamed, wept, and prayed. Over the wild din I heard the clear laughter of a young woman; then it was gone.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN – JONAS

I hungered then for light as a starving man for meat, and at last I risked the Claw. Perhaps I should say that it risked me; it seemed I had no control of the hand that slid into my boot-top and grasped it. At once the pain faded, and there came a rush of azure light. The hubbub redoubled as the other wretched inhabitants of the place, seeing that radiance, feared some new terror was to be thrust among them. I pushed the gem down into my boot once more, and when its light was no longer visible began to grope for Jonas.

He was not unconscious, as I had supposed, but lay writhing, some twenty steps from where we had rested. I carried him back (finding him astonishingly light) and when I had covered us both with my cloak touched his forehead with the Claw. In a short time he was sitting up. I told him to rest, that whatever it was that had been in the prison chamber with us was gone.

He stirred and muttered, "We must get power to the compressors before the air goes bad."

"It's all right," I told him. "Everything is all right, Jonas." I despised myself for it, but I was talking to him as if he were the youngest of apprentices, just as, years before, Master Malrubius had spoken to me. Something hard and cold touched my wrist, moving as if it were alive. I grasped it, and it was Jonas's steel hand; after a moment I realized he had been trying to clasp my own hand with it. "I feel weight!" His voice was growing louder. "It must be only the lights." He turned, and I heard his hand ring and scrape as it struck the wall. He began talking to himself in a nasal, monosyllabic language I did not understand.

Greatly daring, I drew out the Claw again and touched him with it once more. It was as dull as it had been when we had first examined it that evening, and Jonas became no better; but in time I was able to calm him. At last, long after the remainder of the room had grown quiet, we lay down to sleep. When I woke, the dim lamps were burning again, though I somehow felt that it was yet night outside, or at least no more than earliest morning.

Jonas lay beside me, still asleep. There was a long tear in his tunic, and I saw where the blue fire had branded him. Recalling the man-ape's severed hand, I made certain no one was observing us and began to trace the burn with the Claw. It sparkled in the light much more brightly than it had the evening before; and though the black scar did not vanish, it seemed narrower, and the flesh to either side less inflamed. To reach the lower end of the wound, I lifted the cloth a trifle. When I thrust in my hand, I heard a faint note; the gem had struck metal. Drawing back the cloth more, I saw that my friend's skin ended as abruptly as grass does where a large stone lies, giving way to shining silver. My first thought was that it was armor; but soon I saw that it was not. Rather, it was metal standing in the place of flesh, just as metal stood in the place of his right hand. How far it continued I could not see, and I was afraid to touch his legs for fear of waking him.

Concealing the Claw again, I rose. And because I wanted to be alone and think for a few moments, I walked away from Jonas and into the center of the room. It had been a strange enough place the day before, when everyone was awake and active. Now it seemed stranger still, a ragged blot of a room, frayed with odd corners and crushed under its lowering ceiling. Hoping that exercise would set my mind in motion (as it often does), I decided to pace off the room's length and width, treading softly so as not to wake the sleepers.

I had not gone forty paces when I saw an object that seemed completely out of place in that collection of ragged people and filthy canvas pallets. It was a woman's scarf woven of some rich, smooth material the color of a peach. There is no describing the scent of it, which was not that of any fruit or flower that grows on Urth, but was very lovely.

I was folding this beautiful thing to put in my sabretache when I heard a child's voice say, "It's bad luck. Terrible luck. Don't you know?"

Looking around, then down, I saw a little girl with a pale face and sparkling midnight eyes that seemed too large for it; and I asked, "What's bad luck, Mistress?"

"Keeping findings. They come back for them later. Why do you wear those black clothes?"

"They're fuligin, the hue that is darker than black. Hold out your hand and I'll show you. Now, do you see how it seems to disappear when I trail the edge of my cloak across it?" Her little head, which small though it was seemed much too big for the shoulders below it, nodded solemnly. "Burying people wear black. Do you bury people? When the navigator was buried there were black wagons and people in black clothes walking. Have you ever seen a burying like that?" I crouched to look more easily into the solemn face. "No one wears fuligin clothes at funerals, Mistress, for fear they might be mistaken for members of my guild, which would be a slander of the dead—in most cases. Now here is the scarf. See how pretty it is? Is it what you call a finding?" She nodded. "The whips leave them, and what you ought to do is push them out through the space under the doors. Because they'll come and take their things back." Her eyes were no longer on mine. She was looking at the scar that ran across my right cheek.

I touched it. "These are the whips? The ones who do this? Who are they? I saw a green face."

"So did I." Her laughter held the notes of little bells. "I thought it was going to eat me."

"You don't sound frightened now."

"Mama says the things you see in the dark don't mean anything—they're different almost every time. It's the whips that hurt, and she held me behind her, between her and the wall. Your friend is waking up. Why are you looking so funny?"

(I recalled laughing with other people; three were young men, two were women of about my own age. Guibert handed me a scourge with a heavy handle and a lash of braided copper. Lollian was preparing the firebird, which he would twirl on a long cord.)

"Severian!" It was Jonas, and I hurried over. "I'm glad you're here," he said when I was squatting beside him. "I . . . thought you'd gone away."

"I could hardly do that, remember?"

"Yes," he said. "I remember now. Do you know what this place is called, Severian? They told me yesterday. It's the antechamber. I see you already knew."

"No."

"You nodded."

"I recalled the name when you pronounced it, and I knew it was the right one. I . . . Thecla was here, I think. She never considered it a strange place for a prison, I suppose because it was the only one she had seen before she was taken to our tower, but I find I do. Individual cells, or at least several separate rooms, seem more practical to me. Perhaps I'm only prejudiced." Jonas pulled himself up until he was sitting with his back to the wall. His face had gone pale under the brown, and it shone with perspiration as he said, "Can't you imagine how this place came to be?

Look around you."

I did so, seeing no more than I had seen before: the sprawling room with its dim lamps.

"This used to be a suite—several suites, probably. The walls have been torn away, and a uniform floor laid over all the old ones. I'm sure that's what we used to call a drop ceiling. If you were to lift one of those panels, you'd see the original structure above it."

I stood and tried; but though the tips of my fingers brushed the rectangular panes, I was not tall enough to exert much force on them. The little girl, who had been watching us from a distance of ten paces or so, and listening, I feel sure, to every word, said, "Hold me up and I'll do it." She ran toward us. I lifted her and found that with my hands around her waist I could easily raise her over my head. For a few seconds her small arms struggled with the square of ceiling above her. Then it went up, showering dust. Beyond it I saw a network of slender metal bars, and through them a vaulted ceiling with many moldings and a flaking painting of clouds and birds. The girl's arms weakened, the panel sunk again, with more dust, and my view was cut off. When she was safely down, I turned back to Jonas. "You're right. There was an old ceiling above this one, for a room much smaller than this. How did you know?"

"Because I talked to those people. Yesterday." He raised his hands, the hand of steel as well as the hand of flesh, and appeared to rub his face with both. "Send that child away, will you?" I told the little girl to go to her mother, though I suspect she only crossed the room, then made her way back along the wall until she was within earshot of us.

"I feel as if I were waking up," Jonas said. "I think I said yesterday that I was afraid I would go mad. I think perhaps I'm going sane, and that is as bad or worse." He had been sitting on the canvas pad where we had slept. Now he slumped against the wall just as I have since seen a corpse sit with its back to a tree.

"I used to read, aboard ship. Once I read a history. I don't suppose you know anything about it. So many chiliads have elapsed here."

I said, "I suppose not."

"So different from this, but so much like it too. Queer little customs and usages . . . some that weren't so little. Strange institutions. I asked the ship and she gave me another book." He was still perspiring, and I thought his mind was wandering. I used the square of flannel I carried to wipe my sword blade to dry his forehead.

"Hereditary rulers and hereditary subordinates, and all sorts of strange officials. Lancers with long, white mustaches." For an instant the ghost of his old humorous smile appeared. "The White Knight is sliding down the poker. He balances very badly, as the King's notebook told him." There was a disturbance at the farther end of the room. Prisoners who had been sleeping, or talking quietly in small groups, were rising and walking toward it. Jonas seemed to assume that I would go as well, and gripped my shoulder with his left hand; it felt as weak as a woman's. "None of it began so." There was a sudden intensity in his quavering voice. "Severian, the king was elected at the Marchfield. Counts were appointed by the kings. That was what they called the dark ages. A baron was only a freeman of Lombardy."

The little girl I had lifted to the ceiling appeared as if from nowhere and called to us, "There's food. Aren't you coming?" and I stood up and said, "I'll get us something. It might make you feel better."

"It became ingrained. It all endured too long." As I walked toward the crowd, I heard him say, "The people didn't know."

Prisoners were walking back with small loaves cradled in one arm. By the time I reached the doorway the crowd had thinned, and I was able to see that the doors were open. Beyond it, in the corridor, an attendant in a miter of starched white gauze watched over a silver cart. The prisoners were actually leaving the antechamber to circle around this man. I followed them, feeling for a moment that I had been set free.

The illusion was dispelled soon enough. Hastarii stood at either end of the corridor to bar it, and two more crossed their weapons before the door leading to the Well of Green Chimes. Someone touched my arm, and I turned to see the white-haired Nicarete. "You must get something," she said. "If not for yourself, then for your friend. They never bring enough." I nodded, and by reaching over the heads of several persons I was able to pick up a pair of sticky loaves. "How often do they feed us?"

"Twice a day. You came yesterday just after the second meal. Everyone tries not to take too much, but there is never quite enough."

"These are pastries," I said. The tips of my fingers were coated with sugar icing flavored with lemon, mace, and turmeric.

The old woman nodded, "They always are, though they vary from day to day. That silver biggin holds coffee, and there are cups on the lower tier of the cart. Most of the people confined here don't like it and don't drink it. I imagine a few don't even know about it."

All the pastries were gone now, and the last of the prisoners, save for Nicarete and me, had drifted back into the low-ceilinged room. I took a cup from the lower tier and filled it. The coffee was very strong and hot and black, and thickly sweetened with what seemed to me thyme honey.

"Aren't you going to drink it?"

"I'm going to carry it back to Jonas. Will they object if I take the cup?"

"I doubt it," Nicarete said, but as she spoke she jerked her head toward the soldiers. They had advanced their spears to the position of guard, and the fires at the spearheads burned more brightly. With her I stepped back into the antechamber, and the doors swung closed behind us. I reminded Nicarete that she had told me the day before that she was here by her will, and asked if she knew why the prisoners were fed on pastries and southern coffee.

"You know yourself," she said. "I hear it in your voice."

"No. It's only that I think Jonas knows."

"Perhaps he does. It is because this prison is not supposed to be a prison at all. Long ago—I believe before the reign of Ymar—it was the custom for the Autarch himself to judge anyone accused of a crime committed within the precincts of the House Absolute. Perhaps the autarchs felt that by hearing such cases they would be made aware of plots against them. Or perhaps it was only that they hoped that by dealing justly with those in their immediate circle they might shame hatred and disarm jealousy. Important cases were dealt with quickly, but the offenders in less serious ones were sent here to wait—" The doors, which had closed such a short time ago, were opening again. A little, ragged, gap-toothed man was pushed inside. He fell sprawling, then picked himself up and threw himself at my feet. It was Hethor.

Just as they had when Jonas and I had come, the prisoners swarmed around him, lifting him up and shouting questions. Nicarete, soon joined by Lomer, forced them away and asked Hethor to identify himself. He clutched his cap (reminding me of the morning when he had found me camping on the grass by Ctesiphon's Cross) and said, "I am the slave of my master, far-traveled, m-m-map-worn Hethor am I, dust-choked and doubly deserted," looking at me all the while with bright, deranged eyes, like one of the Chatelaine Lelia's hairless rats, rats that ran in circles and bit their own tails when one clapped one's hands.

I was so disgusted by the sight of him, and so concerned about Jonas, that I left at once and went back to the spot where we had slept. The image of a shaking, gray-fleshed rat was still vivid as I sat down; then, as though it had itself recalled that it was no more than an image purloined from the dead recollections of Thecla, it flicked out of existence like Domnina's fish.

"Something wrong?" Jonas asked. He appeared to be a trifle stronger.

"I'm troubled by thoughts."

"A bad thing for a torturer, but I'm glad of the company."

I put the sweet loaves in his lap and set the cup by his hand. "City coffee—no pepper in it. Is that the way you like it?"

He nodded, picked up the cup, and sipped. "Aren't you having any?"

"I drank mine there. Eat the bread; it's very good."

He took a bit of one of the loaves. "I have to talk to somebody, so it has to be you even though you'll think I'm a monster when I'm done. You're a monster too, do you know that, friend Severian? A monster because you take for your profession what most people only do as a hobby."

"You're patched with metal," I said. "Not just your hand. I've known that for some time, friend monster Jonas. Now eat your bread and drink your coffee. I think it will be another eight watches or so before they feed us again."

"We crashed. It had been so long, on Urth, that there was no port when we returned, no dock. Afterward my hand was gone, and my face. My shipmates repaired me as well as they could, but there were no parts anymore, only biological material." With the steel hand I had always thought scarcely more than a hook, he picked up the hand of muscle and bone as a man might lift a bit of filth to cast it away.