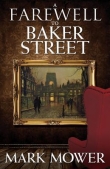

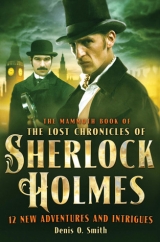

Текст книги "The Mammoth Book of the Lost Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes"

Автор книги: Denis O. Smith

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“It’s no good anyone looking at me,” remarked Mrs Claydon. “I can’t shed any light on it, for I didn’t send the telegram.”

“Have you told anyone about the money in the tobacco jar?” asked Holmes.

“Certainly not,” replied Mrs Claydon.

“Then how could anyone know about it?” Holmes asked the housekeeper again.

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Is it possible, do you think, that you have misremembered the matter, and that the telegram did not actually mention the tobacco jar at all?” queried Holmes. “Perhaps it merely instructed you to bring some money, without specifically mentioning where the money was to be found. Could that have been the case?”

I saw the housekeeper hesitate and frown, but I could not tell what was passing in her mind.

“Perhaps, sir,” said she at length.

“But you are not certain upon the point?”

“No, sir, I am certain. I remember now: it did not mention the tobacco jar, but of course I knew that was where Mrs Claydon kept the money.”

“I see. Some people might think it surprising that in a communication which was doubtless less than a dozen words, you should have been unsure as to whether the words ‘tobacco jar’ occurred or not, but I pass over that. The message instructed you to take five pounds from the jar. Is that correct?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And was that amount in the jar?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In sovereigns?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Here is another mystery, then: how could a stranger to the household have known that such a sum would be available? There cannot be many households in which a sum as large as five pounds is left in an unlocked jar on a mantelpiece.”

“No, sir; it is a lot of money. I was anxious all the time I had it with me, in case I lost any of it, and gave it over to Mrs Claydon as soon as we met, at Waterloo station. I took very great care of it, sir.”

“I do not doubt it, but that is not the point at issue, which is, rather, how anyone outside of this household could have known of the money. Of course, if such a telegram had in fact been sent by Mrs Claydon, the question would not arise, as she must be presumed to know how much money is in her own house, but Mrs Claydon did not send the telegram. You see the problem?”

“Yes, sir,” responded the housekeeper, nodding her head.

“Fortunately, I have a solution.”

“Sir?”

“Yes. What I suggest is that the telegram stipulated neither the tobacco jar nor the sum of five pounds, nor, for that matter, Portsmouth, nor anything else that you mentioned, for the simple reason that the telegram never existed. It is a figment of your imagination, designed to explain your own apparent absence from the house this afternoon.”

“No, sir!” cried the housekeeper in protest, taking a step backwards.

“I imagine that you waited until the maid, Susan, was busy elsewhere in the house, then you opened the front door and rattled the knocker yourself. Moments later, you informed her that a telegram had arrived for you, necessitating a journey to Portsmouth, and that she would therefore have to return home for the day. She is very young, I understand, and would accept what you told her without query. Once she was out of the way, your plan could proceed.”

“No, sir! It’s not true!” cried the housekeeper.

“I further suggest that you did not travel to Portsmouth at all, but were busy in London all afternoon. Later you went down to Waterloo station specifically to intercept Mrs Claydon, which you thought would help to confirm your make-believe story.”

“Madam!” cried the housekeeper, turning to her employer in entreaty. “This is unjust! Why is this gentleman accusing me?”

“You have a sister, I believe?” continued Holmes, ignoring the woman’s protest.

At this she hesitated. Her mouth opened, but she did not speak.

“Come, come,” said Holmes in a genial tone. “It is no crime in this country to have a sister. You need not fear arrest on the grounds of having a sister. You have a sister?”

“Yes, sir,” responded the housekeeper at length, in a reluctant tone.

“Her name, I believe, is Violet,” continued Holmes.

The housekeeper’s jaw dropped, her eyes opened wide with surprise and fear and she flung her hands up to her face.

“How can you know that?” asked she in a strained, cracked voice.

“It is my business to know things,” responded Holmes calmly, regarding her face very closely. “They are pretty names, Violet and Rosemary. Your parents must have been very fond of wild flowers. Your sister, Violet, was, I believe, married to Percival Slattery in 1870, that is to say, seventeen years ago. He later deserted her and treated her very shamefully.”

For a moment, the housekeeper seemed to sway unsteadily on her feet, then she fell to her knees on the floor, clutched her head in her hands and burst into a storm of sobbing.

“Is this true, Rosemary?” asked Henry Claydon after a moment.

She tried to answer, but was sobbing so heavily and loudly that she was unable to form the words. Instead, she nodded her head vigorously.

“Perhaps you could describe to us exactly what occurred today,” suggested Holmes in a soft, kindly tone, “and then we might understand it a little better.”

Again the housekeeper nodded her head, but it was several minutes before she had composed herself sufficiently to begin her account. Then, seated on a chair that Claydon had brought in for her from the dining room, she made the following statement:

“My sister, Violet, is two years older than me. She and I were born and raised here in London, the only children of Patrick and Mary Quinn. When she was fourteen and I was twelve, the family moved to Melbourne, Australia, where my father had hopes of good employment in the gold fields. I became a kitchen maid, then later cook, in the household of Colonel Hayward, who was posted out there at the time. When he and his family returned to England, he asked me to accompany them, which I agreed to do. My sister, meanwhile, had married Percival Slattery at St Paul’s Church in Melbourne when she was twenty-one. Percy was a fine figure of a man, I must say, and I could not fault her decision in that respect. But although fine to look at, and a grand talker, he never achieved anything. He was always speaking of great schemes, and making glorious predictions for their future, but nothing ever seemed to come of any of it. Then, when they had been married a little over two years, he took himself off to some newly discovered gold fields, hundreds of miles from Melbourne, declaring that he would return home a wealthy man. Alas, he never returned at all, and my sister heard a year later that he had been killed in an avalanche. By that time she had a baby girl, for she had been with child when he left her. Her life in Melbourne, where she worked as a nurse, was not an easy one, as I learned from her letters.

“Many years passed. My employer, Colonel Hayward, died, but I was by then very experienced and had no difficulty in finding fresh employment, first with a family at Greenwich, and later with Lord Elvington, who kept a very grand establishment in the West End. His connections with the very highest level of society were extensive, and many great and noble guests would grace his table of an evening. Sometimes I would hear the gentlemen discussing politics, and although I cannot claim that I really understood all that they were saying, I was fascinated by their manner of discourse, and by the weighty matters under discussion. One evening, I heard a visitor mention the name of Percy Slattery, and comment upon something he had said in a recent speech. The name struck my ear with a particular resonance, as you will imagine, but I could not really believe that the man referred to was the same as I had known all those years ago.

“A few days later, however, Lord Elvington gave a dinner for a large number of parliamentarians, and among the names on the guest list was that of Percival Slattery. Impelled by curiosity, I contrived to get a view of this man without being seen myself, and almost fainted with shock when I did. He was somewhat more stolid in appearance now than when I had known him as a young man, but there could be no doubt in my mind that this was indeed my sister’s husband, long presumed dead. It seemed clear what had happened: he had failed in his search for fortune in the gold fields and, no doubt unable to bear the shame, as he saw it, of returning home empty-handed, had taken himself halfway round the world to seek anew for fame and fortune in England. That his personal pride at failing in the gold fields should have been a weightier consideration for him than any bond, either of duty or of affection, for his wife, was entirely consistent with what I knew of his character.

“I hesitated for several weeks before informing my sister of this discovery, for I knew how deeply it would shock and grieve her to think that her husband, and the father of her daughter, was living comfortably in England without a thought for her, while she endured a hard, struggling existence in Australia. Eventually, however, I decided that the truth must be told. What my sister’s feelings were upon learning this news, I will not burden you with. Suffice it to say that she poured out her heart to me in many, many letters. From that day forward, she was determined that she would one day come to England, and confront her faithless spouse.

“More time passed, then, six months ago, having saved up sufficient money to pay for the passage of herself and her daughter, Victoria, my sister arrived in England. After some time spent fruitlessly seeking employment in Southampton, her experience as a nurse eventually helped her secure a position at a doctor’s dispensary in Portsmouth. At the same time, she succeeded in placing her daughter as a tweeny in the household of a retired admiral there. Since then, we have met and discussed the question of her husband several times. The chief difficulty in approaching him lay in what we knew of his character. He has always had such grand social aspirations, such a keen nose for sniffing out the wealthy and titled, among whom he had always desired to move, that to approach him with an appearance of beggary would, as likely as not, elicit only scorn, if not contempt. But if Violet could present herself as comfortably off, then she would, she felt, possess a greater influence over him.

“My employment with Lord Elvington ended, as he took up a post as governor of one of the Indian provinces, and I did not wish to leave England. Mr and Mrs Claydon very kindly offered me employment here, and it was then that Violet and I had the idea that if, on some occasion when my employers were away, Violet could invite Percy here and pretend that it was her own residence, it would exactly suit her purpose. Of course, having devised this scheme, we were impatient to put it into practice. Then, when I learned that Mr Claydon would be absent from home this evening, it seemed the very chance we had been waiting for. If it could be arranged that my mistress, too, was absent for a few hours, then Violet would have the perfect opportunity to meet her husband here.

‘‘I had heard Mrs Claydon speak often, with some concern, of her brother, Leonard, in America, and knew that she would respond readily to any communication from him. My sister therefore sent the telegram this morning from Portsmouth as if from Leonard. Before catching the train to London, she also handed in at the station the brief letter that Mrs Claydon was later given there. I had previously written this myself, copying his hand as well as I could from his letters, which are in the bureau, and sent it down to my sister. She, meanwhile, had composed a letter to her husband, which she sent to me here, so that I could post it at the local post office.

‘‘It was still possible, we thought, that Percival would treat my sister in a high-handed and scornful manner, would adopt a brazen attitude and simply dare her to make any accusation against him. But if he had cause to fear that the whole story of his desertion would inevitably become public knowledge, then he might act differently. To this end, I wrote a letter to Mr Falk, inviting him to come here today, a little after the time set for Percy’s appointment. I had seen Mr Falk’s name in the newspaper, and knew he was a parliamentary reporter, for Mr Claydon generally takes the Standard, and I have sometimes glanced through it when he has finished with it, looking for any mention of my sister’s husband. Mr Falk’s presence here would, I felt, force Percy to act more decently than he otherwise might.”

At this point, Miss Quinn abruptly stopped and burst once more into a torrent of sobbing.

“I am sorry,” she cried at length in a heartfelt tone, her eyes brimming with tears. “I am sorry for all the trouble and anxiety I have caused to everyone. Would that I had never heard the name of Percival Slattery! Would that my sister had never clapped eyes on him again after he had left for the gold fields!”

“Your scheme did not go quite as planned,” remarked Holmes after a moment, as the housekeeper sobbed quietly before us.

“That is correct, sir,” responded she after a moment. “Percival Slattery arrived on time, I stayed out of sight and Violet received him in this room. She had brought with her the old picture of the church, which you see on the wall there. It is the church in Melbourne where they were married. She had hoped that such a reminder of the vows he had made might stir some embers of decency in his soul, but I think that the hope was a vain one. Then she reminded him of the presents they had given each other when they became engaged to be married, and she showed him the little jewelled brooch that she still wore, and asked him if he still had the watch she had given him. Reluctantly, he pulled his watch from his waistcoat pocket and she saw that it was indeed the very one she had given him, inscribed with their names, all those years ago. At that point, Violet’s daughter, dressed in her maid’s uniform, brought in a tray of tea for them.

“‘There is something that you don’t know,’ said Violet to her husband then.

“‘Oh?’ replied he in an unconcerned manner. ‘And what might that be, pray?’

“‘You have a daughter,’ said she.

“At first he dismissed what she said and would not believe her, but as she gave him the details of the matter, he fell silent, and it was evident that he accepted she was speaking the truth. After a moment, she spoke again:

“‘It is she who just served you with your tea.’

“‘No!’ cried he. ‘That was your maid.’

“‘That is she,’ said Violet, and called Victoria back into the room. ‘Percival, meet your daughter! Victoria, meet your father!’

“At this, he sprang to his feet, but the shock of the occasion proved too much for him. He coughed and spluttered and began to weep, but then all at once clutched his chest and cried out in pain. A moment later he had fallen to the ground in a heap.

“I dashed into the room as Violet cried out in alarm, but it was clear at once that there was nothing we could do for him. He had stopped breathing, his eyes were wide and staring, and he was stone dead.

“At that very moment there came a sharp knock at the front door. ‘It must be Mr Falk, the newspaperman,’ said Violet in alarm. ‘Quickly! Help me get Percy into the back room!’

“We dragged him through there as quickly as we could, then Victoria went to admit the visitor. Violet had brought with her from the dispensary at Portsmouth a small bottle of chloral, in case of emergencies, and she decided at once that she would put some into Mr Falk’s tea. ‘It will not hurt him,’ said she. ‘It will just put him to sleep for a little while.’

“A minute or two later, she joined Mr Falk in the sitting room, and shortly afterwards Victoria took in the tea, with a few drops of chloral already in one of the cups. Within a few moments, Mr Falk had fallen into a deep sleep, and we were just carrying him out into the garden when there came another sharp rap at the front door. Victoria ran to answer it as we laid Mr Falk out on the lawn, then Violet joined her daughter at the front door, and found to her horror that the caller was the rightful occupier of the house, Mr Claydon, who had come home after all. Not only that, but she saw that a policeman was at that moment passing down the street. She decided, on the spur of the moment – Lord forgive her for her lies! – to brazen it out. Well, as you know, she succeeded and Mr Claydon departed. Then the three of us, Violet, Victoria and myself, left by the back door, through the garden and out into the back lane behind the house. So hurried was our departure that we forgot to remove the pictures Violet had brought with her, as you will have noticed. I travelled with Violet and her daughter as far as Waterloo, and saw them onto the train there. Then, seeing that a train from Southampton was due within the hour, I waited there until it arrived, when I met up with Mrs Claydon.”

“What did you intend to do about the body of Mr Slattery?” asked Holmes.

“I thought that Mrs Claydon and I could find it when we got back here, and then notify the authorities,” replied Miss Quinn. “As everything that could have gone wrong with our scheme seemed to have done so, I did not think that anything further could go amiss, until we reached Kendal Terrace and saw a police van waiting there and a huge crowd of people in the street.”

“This is a very grave business,” said Inspector Spencer, rising to his feet. “I must ask you to accompany me to the station and make a full statement there,” he continued, addressing Miss Quinn. “Failure to notify the authorities of a death is a very serious offence.”

“I was going to do so,” returned the housekeeper.

“So you say. But so everyone says who is arrested for not doing so. Then there is the question of the wilful assault on the person of Mr Falk by the administration of a dangerous drug, not to mention a possible charge of blackmail, extortion or demanding money with menaces from the deceased.”

“The woman was his wife, Spencer,” interjected Holmes, “and as such was surely entitled to some claim for financial support from him.”

“Perhaps so – if she really was his wife,” returned the policeman in his most official tone, “but that will be for others to consider. I will make my report and pass it to my superiors and they will decide what action should be taken.”

“Well, I’m off, anyhow,” said Linton Falk, springing to his feet. “What a story! I am obliged to you, Mr Holmes, for suggesting that I delay my departure. I thought I had a story then, but I have an even better one now!”

“You just make sure you stick to the facts, young man!” said Spencer in a stern tone, as the newspaperman made to leave the room. “You reporters are all the same: give you one fact and you make up three!”

A minute later, Holmes and I had left the house that had been the scene of such mysterious and surprising events, and were walking up the main road in the twilight.

“You can hardly maintain, after the events of this evening,” I remarked, “that the present age has ceased to produce interesting mysteries.”

“That is true,” conceded my companion. “And yet, after all, it was a simple affair.”

“I confess it did not strike me in that way,” I returned with a chuckle.

“Well, of course, it possessed a certain superficial complexity, but beneath the surface it was simple enough.”

“What do you think will become of Miss Quinn?”

“It is hard to say. Claydon strikes me as a decent and forgiving soul, so I don’t imagine he will press charges of any kind; but I doubt he will keep her on, for the bond of trust, which is essential between those sharing a household, has been broken. Besides, he has his wife’s opinion to accommodate, and she is, I perceive, made of somewhat sterner metal than her husband.”

“You are probably right,” I concurred. “What led you to suspect that the housekeeper was at the bottom of it all? And how on earth did you know she had a sister called Violet, and all the rest of it?”

“Ah! There you touch on the one really interesting point in the whole business,” replied my friend with enthusiasm. “Should you ever include an account of this case in that chronicle of my professional life which you have threatened for so long, Watson, you must ensure that you stress the importance of the slivers of glass on the sitting-room carpet, and the fact that there were two clocks in the room. These things constitute a perfect example – a text-book illustration, one might say – of the maxim that the solution of a problem is generally to be found by a close examination of its details.

“You see,” he continued, “when we entered the sitting room for the first time, upon our arrival at the house, Claydon remarked almost at once upon the unknown picture on the wall, the photograph upon the piano and the missing roses. But the first thing that caught my own eye was a reflected glint of light from something upon the floor. When I examined it, I found that it was a tiny sliver of glass. Then I saw a second, and a third, nearby, beneath one of the chairs. The glass was thin, but seemed fairly strong, and each of the slivers had a slight curve to it. It struck me that they might be from a broken wine glass, but I kept an open mind on the matter.

“When we discovered Slattery’s body, a quick investigation revealed that the glass on the face of his watch was broken. As I examined what remained of it, I could not doubt that the particles of glass in the sitting room were from the same source. Clearly the damage to the watch had occurred in the other room. I tried to close the cover of the watch, which was open, and found that I could not do so, as it had been twisted slightly on its hinges. This would have required some force, and I conjectured that the damage to the watch had been caused when its owner had fallen unconscious to the floor. I tried the watch in the waistcoat pocket. It was a tight fit and would not have slipped out as he fell. Therefore he had had it in his hand at the time he fell. This was suggested also by the damage to the hinge, which must have occurred while the lid was open.

“The shards of glass informed me that it was in the sitting room that Slattery had fallen. But why did he have his watch in his hand in the sitting room? For in the sitting room there is not one clock, but two, both working and both showing the correct time.”

“He might have taken it from his pocket by sheer force of habit,” I suggested, “oblivious to the presence of other timepieces in the room.”

“Yes, that is possible. It is also possible that he had taken it from his pocket not to see the time but to make a gesture, to indicate, say, that he was a busy man, whose time was of some value. But what seemed equally possible was that he had been consulting the watch for some other purpose altogether.”

“I cannot imagine what that could have been.”

“No more could I. But one must always allow in one’s calculations not merely for the unknown, but for the unimagined. I inspected the watch closely, with the aid of a lens. Upon the underside of the lid, rubbed almost to invisibility, was an inscription. At the top were two large letters, ‘P’ and ‘S’, twined together in a monogram. These initials, of course, matched those I had already observed on the dead man’s cuff-links. Below the monogram was a date, 1870, and, below that, two lines of writing, which I deciphered only with considerable difficulty. The first said ‘fond affection’, and the second ‘Violet Q’. Of course, the initial ‘Q’ at once suggested the surname ‘Quinn’, and the fact that ‘Violet’ and ‘Rosemary’ are both flower-names seemed too much of a coincidence to be the result of mere chance. I therefore conjectured that the woman, Violet, who had evidently given the watch to the dead man, was the sister of Rosemary Quinn, the Claydons’ housekeeper. There was one other possibility, I considered, which was that these two were one and the same person, namely Violet Rosemary Quinn, who had perhaps been known as ‘Violet’ when she was younger, but chose now to be known as ‘Rosemary’. But considering that there was definitely another woman involved in the matter – the woman whom Claydon had found to be in possession of his house when he returned from work – I discounted this possibility. The suggestion that that woman was indeed the sister of Claydon’s housekeeper was given added support by his observation that her appearance struck him as vaguely familiar. So already, you see, I had established a probable link between one of the usual members of the household and the apparent strangers who had taken possession of the house this afternoon.”

“Your reasoning seems very sound,” I remarked. “I am fascinated!”

“Thank you,” said Holmes. “Now, when Falk came to examine the body, and identified it as that of Percival Slattery, he informed us that Slattery had been born and bred in Australia. This instantly strengthened my theory, for Claydon had remarked that the woman who met him at his front door, although well spoken, had had an accent that he had been unable to place. Perhaps, I conjectured, her accent was an Australian one, and perhaps she had known Slattery when they both lived there. If so, she had probably given the watch to him then. As I considered this, the meaning of the photograph of the child on the piano became all at once very clear to me. There was, if you recall, a pencilled inscription on the mount of the photograph, which read ‘Victoria, O Victoria’. This appeared to be an ejaculation or lament of some kind, although the significance was not clear. But what if the ‘O’ in the inscription was not an ejaculatory ‘O’, as it appeared to be, but had been intended as an abbreviation of the word ‘Of’? I examined the photograph closely through my lens and, sure enough, immediately after the ‘O’ was the very faintest of pencil marks, a mere tick, but one which had clearly been intended as an apostrophe. The child’s name was therefore Victoria, and, evidently in a moment of whimsy, someone, probably the child’s mother, had inscribed the photograph ‘Victoria of Victoria’, Victoria being, of course, one of the colonies of Australia. That, therefore, was where the child had been living at the time the photograph was taken.

“But the presence of this mysterious and previously unseen photograph in the room where Slattery was met by Rosemary Quinn’s sister could, realistically, mean only one thing: that the child was his. The presence, furthermore, of the old picture of a church suggested that something to do with a wedding was the issue between them. Either he had married her and then deserted her, or he had perhaps jilted her at the altar rail. In either event, the whole case seemed now as clear as crystal, and I was able to conjecture – accurately as it turned out – the reason Falk had been invited there, and what it was that had caused Slattery to have a seizure. The only task that remained was to unsettle the housekeeper’s composure, so that when I mentioned her sister she would already be in a nervous state, be unable to conceal her surprise, and would very likely give herself away. She herself had presented me with the opportunity to ask unsettling questions by her somewhat vague description of the telegram she claimed to have received, and its unlikely contents.

‘‘Of course, logically speaking, if the telegram really had included a reference to the tobacco jar on the mantelpiece, it would, although surprising, not necessarily have proved anything one way or the other against the woman. But I perceived as soon as I questioned her on the point that she herself could see that it sounded distinctly unlikely. At that moment, her edifice of untruth began to collapse about her, and the rest you know.”

I stopped, turned to my companion and held out my hand. “Congratulations!” said I warmly.

“What is this?” returned he with a puzzled smile, shaking my hand.

“Your conduct of the case was exemplary,” I explained. “I have known you some years now, Holmes, and have seen you solve a good many cases – many, no doubt, of greater difficulty than this one. But I don’t know that I have ever seen a more accomplished and workmanlike demonstration of the art of detection!”

“Well, thank you, Watson,” said my friend, and I could see that he was quite affected by my sincere approbation. “It is kind of you to say so. Now, here is something else for you to consider,” he continued in a lighter tone, “as we traverse these seemingly endless streets of south London. Many of them are not entirely unattractive – indeed, Kendal Terrace itself is only wanting a tree or two to make it a very pleasant little thoroughfare – but they are, in the main, somewhat banal and unromantic. That can scarcely be denied. Is it not strange, then, that in such unpromising terrain should bloom such brilliant and fascinating flowers as these cases, which it is my delight to investigate, and yours to record? For it cannot be denied that the dull grey streets of London present the finest field there is for those who take pleasure in such things. It is as if Nature must always find a way of compensating, just as, in the densest of tropical jungles, so I am informed, where the trees grow so closely together that the ground is in constant shade, there flourish the brightest and most spectacular blooms that nature can show.”

“It seems a somewhat fanciful notion,” I remarked. “What about sparrows? The sparrow is undoubtedly the most common bird in cities and towns, and should, therefore, on your theory, be surpassingly beautiful. But whatever other good points it may have, the sparrow is undoubtedly the dullest-looking bird imaginable.”

Holmes laughed, in that strange, silent way that was peculiar to him.

“You are a good fellow, Watson,” said he at length. “You anchor me to reality when my flights of fancy threaten, like a runaway balloon, to carry me off to the dangerous reaches of the upper atmosphere! But here is a cab, trundling empty back to town!” he continued, stepping to the edge of the pavement and holding up his hand. “Let us take a ride to the Strand. I understand that a new restaurant has recently opened there, of which very favourable reports have been given!”