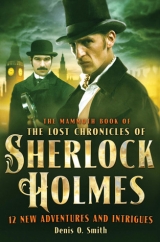

Текст книги "The Mammoth Book of the Lost Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes"

Автор книги: Denis O. Smith

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“What nonsense!” cried the secretary. “This is an outrage! How dare you say such things, Blogg!” Then he turned to Holmes. “I don’t know how you have persuaded this simpleton to lie in this way,” said he in a bitter tone, “but you will not get away with it!”

“It won’t do, Northcote,” returned Holmes, shaking his head. “These displays of outrage and remorse ring equally hollow. You murdered Sarah Dickens and forged the note that was found by the pool, to throw suspicion onto John Reid. You also placed one of his cufflinks, which you had found or stolen, into a pocket of the dead girl’s dress, to make the public suspicions against him even stronger. You then destroyed his father’s letters to him and sent him substitute letters of your own creation, to prevent his responding to the rumours, which you yourself had caused.”

The secretary attempted to laugh, but it was a hoarse, harsh cry that escaped his lips. “Why should I kill Sarah Dickens?” he cried. “Why, she did not interest me at all!”

“No,” said Holmes. “I agree. She did not interest you. Rather, she was a danger to you. She knew something about you that you did not wish anyone else to know.”

“And what was that, pray?” demanded Northcote in a sneering tone.

“That you had been making free with Colonel Reid’s private papers, forging his signature and helping yourself to his money.”

What happened next remains as little more than a blur in my memory. I have mentioned that upon the desk in the centre of the room was a very large globe. Now, with a sudden lunge, Northcote grasped this globe with both hands, lifted it from its stand and hurled it across the room to where we stood. There were cries, Miss Blythe-Headley screamed, and in the same instant the secretary dashed out through the French windows, into the garden. For a split second we all remained transfixed by this sudden eruption of violence, then, with a pitiful cry and an expression of the utmost agony upon his features, Colonel Reid collapsed to the floor like a rag doll.

“Good God!” cried his son in alarm.

“He has had a seizure!” I cried. “Stand back!” Quickly, I bent down and examined the limp, prostrate figure. His haggard face was a dull grey colour and his lips had turned purple. For a moment I feared that he was beyond all human help, but as I loosened his collar and desperately examined him for signs of life, there came the faintest of breaths from his dry lips. “Is there a fire lit in his bedroom?” I asked his son.

“There’s one laid ready,” replied he. “We’ll put a match to it at once.”

“Then help me carry him to his bed. We must keep him warm and make him as comfortable as possible.”

“Northcote will be getting away!” cried someone behind me as we carried the old man from the room and turned up the stairs.

“He will not get far,” I heard Holmes respond. “I have sentries posted in the garden for just such an eventuality.”

It was some time before I was able to return to the library. I had done all I could for Colonel Reid, sent his servant for the family physician and left him in the care of his son and the housekeeper. As I rejoined the company downstairs, they were discussing the apprehension of Northcote. I gathered that he had been brought back to the library, and that Holmes had instructed that he be taken at once to the constable in Topley Cross, with a message of explanation which Holmes himself had written.

“So,” said Admiral Blythe-Headley, “you expected North-cote to flee in this way?”

“I thought it not unlikely,” returned Holmes. “My sentries, as you saw, were Jack Blogg, father of Noah, and John Dickens, brother of the dead girl. He naturally has an interest in seeing the truth established, and justice done. He is employed at Topley Grange, I understand, Admiral.”

“That is so. He assists his father on their own farm in the mornings and works in our gardens in the afternoons. We employ several of the local smallholders in this way at various times of the year. They are by far the best workers, we have found.”

“It was Dickens that damaged your garden bench.”

“What!” cried the admiral. “The blackguard! He will never work for me again!”

Holmes held up his hand. “Do not rush to decisions, I pray you,” said he. “This whole business has been marked by overhasty judgements, almost all of which have been proved wrong. You must understand that Dickens has been sorely afflicted by his sister’s death. He may appear a somewhat rude and unpolished young man, but he has a good heart, and had, I believe, a deep and genuine affection for his sister. I am sure he no more feels the sentiments he carved into your woodwork than would Captain Reid himself, whom you previously accused of it. But on the day last week that Reid visited Topley Grange, Dickens was working in the gardens, and was incensed that this man whom he regarded as morally responsible for his sister’s death should, as he saw it, be renewing his social round as if nothing were amiss. Consumed with rage, he determined to do all he could to further wound Reid’s standing in the district. He correctly judged that if he damaged the bench in the way he did, Reid would be blamed for it.”

“How did you discover that Dickens was responsible?” I asked.

“Mr Yarrow had mentioned to us that Dickens had been employed at Topley Grange on the day of his sister’s death, and I thought it likely that he was still so employed. If so, it seemed a distinct possibility to me that he was responsible for the damage, for I was already convinced that it was he that sent the white feather to Reid.”

“Why so?” I asked

“The yard at Hawthorn Farm, as you no doubt observed, is littered with white duck feathers that are precisely the same as the feather Reid received. In addition, a blank sheet had been torn from the girl’s exercise book, as you yourself remarked, Watson, and this, as I observed, exactly corresponded to the sheet that enclosed the feather, marked with the initials S. D.”

“How came Dickens, a man so full of hatred for Captain Reid, to be your ally?” asked Mary Blythe-Headley in puzzlement. “I should have expected his attitude to you to have been one only of hostility.”

“And so it was, when we spoke to him yesterday, as Dr Watson will confirm. But when I called to see him very early this morning, before he had left the house, I was armed with the knowledge – or conviction, at least – that it was he who had sent the anonymous letter to Reid and damaged the bench, by both of which actions, I assured him, he had laid himself open to criminal proceedings. By this threat I secured his attention and, little by little, managed to convince him that the deep hostility he held towards my client was quite misplaced. It was steep, steep work, I can assure you, but in the end I succeeded. I think you will find, Admiral, that Dickens will henceforth prove to be an honest worker, and if you can forgive him his one lapse, will never again damage your property.”

The admiral appeared unmoved by my friend’s plea for forgiveness on behalf of his errant gardener, but then his daughter spoke out.

“Oh Father,” said she, “have a little charity! It is I who am insulted by the carving on the bench, and I certainly don’t care about it! You fear that you have been led to make a fool of yourself in sending that bill to Colonel Reid, but you should not punish Dickens simply because you feel foolish. None of these things would have occurred if only you and Anthony had had a little more confidence in Captain Reid, and had not been so hasty to think the worst of him.”

Admiral Blythe-Headley appeared angry at this lecture from his daughter. He opened his mouth to speak, but closed it again without saying anything, as Captain Reid re-entered the room.

“How is your father?” asked Mary Blythe-Headley in a voice of concern.

“He is sleeping peacefully now,” returned Reid. “He appears comfortable enough, and we must hope that, with rest, he will recover. But, pray tell me what has happened while I have been absent.”

In a few words, Holmes apprised his client of all that had occurred.

“This is a simply astounding business,” said Reid with a shake of the head, as Holmes finished speaking. “What on earth led you to the conclusion that Northcote lay behind it all? And how did you know that Noah Blogg knew more of the matter than anyone had ever supposed?”

“As it happens, those two aspects of the matter came together in one moment of enlightenment, from my point of view,” Holmes replied. “Dr Watson and I had an appointment yesterday afternoon to meet Mr Yarrow by the Willow Pool in Jenkin’s Clump. We were standing near the pool when he arrived, and as I saw him at the top of the hill, it passed briefly through my mind that we were probably very close to the spot upon which Noah Blogg had been standing when you encountered him last week, and that the vicar, who was on the path from here to the pool, was at the same place as you had been when Blogg first saw you. It was also, I might add, at almost exactly the same time of day, a little after two o’clock in the afternoon. This coincidence might have passed from my mind as swiftly as it had entered it, but for one singular fact: as I looked up the steep pathway, waiting to greet the vicar, I realized all at once that I could not see him.”

“What on earth do you mean?” asked Reid in a tone of puzzlement.

“It was, as I say, shortly after two o’clock on a very sunny day, and the path from here to Jenkin’s Clump runs as you are aware, from south to north. As I looked up the hill, the sun lay almost directly behind Mr Yarrow, and all I could see of him was a black silhouette. It really would have been impossible for me to swear whether the man I saw were he or not. It must have been precisely the same for Blogg when he saw you there last week, on what, as you described it to us, was also a very sunny day. You could see clearly that it was he, but he could not possibly have known that the dark figure he saw at the top of the path was you. Considering that you had been back in the parish for scarcely twenty-four hours, and that Blogg was probably unaware at that time of your return, it becomes even less likely that he recognized you. Yet, as you recounted to us the other day, he looked up at you for only the briefest of moments before letting out a howl of fear and fleeing, as if for his life, through the woods. Clearly, he was in mortal terror of someone, but the more I considered the matter, the more convinced I became that that someone was not you.

“But if not you, then who could it be? What other young man of a roughly similar height and stature might be walking on the path from Oakbrook Hall? Clearly, the most likely candidate was your father’s secretary, Northcote. But this raised further questions: why should Blogg be in such fear of anyone, and why, in particular, should he be in such fear of Northcote? Dr Watson and I had met Blogg earlier in the day, and had found him an amiable and friendly young man. It was clear, however, that despite his fine physique, his simple cast of mind gave him a certain timidity of manner. Such a young man, I judged, might well be cowed into fearfulness by threats from someone with a more powerful character than his own. But why should North-cote, or anyone else, have threatened him? Then I recalled that during his interview with us, by the Willow Pool, in which the subject of Sarah Dickens had been raised, his gaze had continually wandered, involuntarily as it appeared, to a particular spot in the water, close by where we were standing.

“Now, as I was later to learn from Mr Yarrow, this was not the place where the dead girl’s body had been found, and yet it seemed to hold a fascination for Noah Blogg. Could it be, I conjectured, that he had witnessed something there involving Northcote, and that the latter had threatened him in some way, in order to secure his silence? This conjecture, I need hardly add, was strengthened considerably when, by the process of argument I described to you earlier, I concluded that the spot which held such a morbid fascination for Blogg was indeed the very spot on which Sarah Dickens had been murdered. The more I reflected on the matter, the more I became convinced that it was Northcote who had murdered Sarah Dickens, for the hypothesis accorded with every other fact of which I was aware.

“Clearly, it was imperative that I find a way to overcome the fear that had been planted in Blogg’s breast, and persuade him to tell what he knew. I could, I judged, present a reasonably compelling case without Blogg’s testimony, but to have it would undoubtedly strengthen my position considerably. I realized that to gain his trust on such an important matter would be no mean achievement, but I am glad to say I eventually succeeded this morning, with considerable assistance, I must record, from Blogg’s father, whom I had earlier managed to persuade of the truth of the matter.”

“Thank the Lord you did succeed!” cried Reid.

“You have performed a very great service to all of us, Mr Holmes,” said Mary Blythe-Headley. Holmes bowed his head in acceptance of the compliment as she continued, “Those who doubted John’s honesty and integrity, and who doubted, also, your abilities and motives, owe you both a sincere and profound apology.”

There was an uncomfortable silence in the room for a moment, then Admiral Blythe-Headley stepped forward and extended his hand.

“I regret greatly,” said he in a gruff voice, “the manner in which I addressed you last night, Mr Holmes. I was guilty of gross rudeness. Please accept my sincerest apologies.”

Holmes nodded as he took the hand that was offered to him. “You were guilty, perhaps, as I observed earlier, of being a trifle hasty in your judgements.”

“I have often felt, during the last three years,” said Anthony Blythe-Headley abruptly, “that my father’s great animosity towards Reid was borne at least partly from an unstated, and perhaps unacknowledged, fear that I had been involved in some way with the dead girl. No, Father, do not protest! I know it to be true; I have read it often in your eyes. I need hardly say that such a fear was quite groundless, but I resented my father thinking such a thing of me, and in my stupidity I blamed Reid for causing him to have such thoughts.” He paused and shook his head. “I used to think that I was such a clever fellow, but my pretensions to intellect have been shamed by this gentleman,” he continued, indicating Holmes. “He alone has used his brain in an honourable and worthy manner!” He paused again. “It is clear to me now that I am the most stupid dolt in the parish! And to think that all along it was Northcote that had been involved with the girl!”

“I doubt it was as simple as that,” said Holmes with a shake of the head.

“I do not follow you,” said Anthony Blythe-Headley.

“Regrettably, it must be admitted that men and women do sometimes murder those with whom they have been affectionate, but not usually so quickly as in this instance, and we must suspect that the true motives in this case have not yet come to light. What does seem very likely, however, is that Northcote’s involvement with Sarah Dickens was not quite as it appears, and that any display of affection on his part was feigned merely to ensure her silence for a few weeks until he could seal her lips permanently. That he did feign some affection is suggested, I believe, by a page which has been cut from her exercise book of poems: it has been very neatly removed with a pair of nail scissors, and we must suppose it was done by the girl herself. The page is nowhere in evidence now – I have questioned John Dickens on the point – so we may further suppose that she gave it to Northcote. Very likely, that cold and heartless man feigned an interest in her poetry, as he had feigned an interest in the girl herself, and requested it. She would have been flattered by this request, not realizing that he wanted the page only to have a sample of her handwriting from which to prepare the note he intended to leave in Jenkin’s Clump when he had murdered her. If that page ever turns up among his papers, incidentally, I’ll warrant that it contains no instances of the letter ‘f’.”

“You speak of Northcote wishing to ensure her silence,” interrupted Reid in a tone of some puzzlement, “but about what, pray?”

“Something she knew about Northcote himself,” replied Holmes, “something he did not wish anyone to know. It is a point, I admit, which exercised my mind for some time until I hit upon a solution. For how could a local peasant girl like Sarah Dickens learn anything of significance about a man such as Northcote, who occupied a station far removed from her experience and knowledge?”

“It does seem a trifle unlikely,” concurred Reid.

“Indeed; unlikely, but not impossible. It seems to me probable – although here I stray into the realm of conjecture – that this whole business began on the day that Sarah fainted from the heat when picking apples in the orchard here, an incident that Mr Yarrow described to me. If you will recall, Captain Reid, you helped carry her to the house.”

“I remember it well. We brought her into this very room, through the French windows, and laid her on the couch in the corner there.”

“So I understand. Mr Yarrow further mentioned that she was attended by the housekeeper. Now, let us suppose that the housekeeper, having satisfied herself that the girl was comfortable and in no danger of a further attack, had left her alone here for a time. Let us further suppose that, by chance, your father’s secretary happened to enter this room during the period the girl was lying here alone. He would not have known she was here, and she would not yet be fully recovered, so would be lying quite still. Under the circumstances, it is not impossible that he would have failed to see her. His view of the couch as he entered the room would have been partly obscured by this little table and the large vase upon it, and his thoughts would perhaps have been absorbed by his reason for entering the room.”

“What was that, do you suppose?” queried Reid.

“Perhaps to do something which he did not wish anyone to witness,” replied Holmes. “He may have intended to examine or abstract some private papers of your father’s in the desk over there. He would know that you and your friends were all out of the house, working in the orchard, and thus would not interrupt him.

“We may further conjecture that, as he was engaged upon his secret, furtive work, something, some slight movement of the girl’s, perhaps, caused him to look up, and he saw, no doubt to his very great alarm, that she was watching him.”

“I cannot see why the girl’s presence should have caused him any great alarm,” protested Reid. “After all, she could not have appreciated that he was engaged in anything underhand or dishonest.”

“Perhaps not,” returned Holmes. “But knowledge of his own guilt can have a powerful and disturbing effect upon a man’s reason and judgement. The result is not infrequently mental panic, and the conviction that others know more than they in fact do. The panic that would have gripped Northcote at such a moment would have arisen as much, therefore, from his own sense of guilt as from the girl’s presence. He would have seen only that, should she have chosen to do so, Sarah Dickens could have exposed his shameful dishonesty to the world, and this threat would have loomed above every other consideration in his mind. He is, however, a very cunning and deceitful man, and I have little doubt, therefore, that he spoke in a friendly and flattering manner to the girl, and perhaps in the course of the conversation, made an arrangement to meet her again in a few days’ time. That, I suggest, is how the connection between the two of them began. The girl was young and no doubt appeared impressionable. It must have seemed no difficult task to an educated man like Northcote to turn her head and manipulate her affections. On his side the arrangement would have been one of expediency only, a way to gain a little time until he could dispose permanently of the threat that he considered she posed to him. We may imagine he began at once to plan the removal of that threat.”

“It still seems scarcely credible,” I interjected, “that anyone would so swiftly contemplate murder in such circumstances.”

“Perhaps so, Watson, but we do not yet know the extent of Northcote’s dishonesty. Perhaps his hidden crimes are yet greater than I have supposed. He may have been so deeply mired in deceit that he could see no other way out. Nor do we know the true nature of his character. Perhaps, despite the quiet and reserved appearance he presents to the world, he is a man easily moved to violence when his plans are thwarted. The annals of crime are full of such men. I have myself known several.”

“But surely he could have found some other way to prevent the girl speaking of what she had seen,” I persisted. “He could simply have dismissed the matter as of no consequence, for instance, and hoodwinked the girl in that fashion.”

“Perhaps he attempted such a stratagem,” returned Holmes, “and met with no success. Perhaps the girl said something, which indicated to him that she understood all too well the nature of what she had witnessed, and made it clear that any further attempts at deception on his part would be unavailing. As I have frequently had cause to observe, the simplest of people can have surprisingly accurate intuitions as to the motives and character of others. What seems likely, anyway, is that however agreeably he may have spoken to her, and however flattered she may have been by his attentions, she still, nevertheless, considered that she had some hold over him, and was disagreeably pressing in her attentions.”

“Why do you say that?” asked Reid.

“I feel certain that the window that was broken shortly before your departure for India was broken by Sarah Dickens herself. You blamed it on village boys who had been playing in the orchard earlier, but I always thought that unlikely: the broken window was that of the upstairs study, which is on the opposite side of the house from the orchard. I think it more than probable that Sarah, anxious to hear when she would see Northcote again, endeavoured to communicate with him by throwing pebbles up at the lighted window of the study, in which she knew he would probably be working. Unfortunately, we must suppose, her throw was a little over-vigorous.”

“What you are suggesting, then,” said Reid after a moment, “is that Northcote has been swindling my father in some way?”

“I think it highly probable. It is by far the most likely motive for the crime. The account you gave me last week of your family’s affairs suggested that Northcote had advanced quite quickly after his arrival here from simply being your father’s amanuensis to a position of greater confidence and intimacy. I believe he found the temptation to abuse that position too great to resist.”

“Wait a moment!” cried Reid abruptly. “Hidden in the bottom of Northcote’s wardrobe, where I found my satchel, were many bundles of documents and sheets of paper covered with figures. I was so excited then at finding my satchel that I did not give the other things any consideration, but now that I think about it, I am certain they were private papers of my father’s, including a copy of his will. Oh Lord!” he cried all at once in a tone of desperation. “Whatever can I do?”

“You must institute a thorough examination of your father’s affairs at once,” said Holmes in a firm voice, “and seek the advice of the best lawyer in West Sussex. I have little doubt that such an examination will reveal that fraudulent transactions have taken place. You must remember that Northcote has already successfully counterfeited both your father’s hand and that of the dead girl. He may well have signed your father’s name to many things of which no one has any knowledge.”

“This is almost too much for my brain to absorb!” cried Reid, shaking his head. He looked in turn at each of us, an expression of stupefaction upon his features, as if appealing for our help.

“The actions of my family have been shameful,” said Anthony Blythe-Headley abruptly, “and I am sure we would wish to do anything that might help to expunge that shame. I for one should be very pleased to do anything you wish, Reid, to help you to sort out what must be done.”

“Do not falter now, Reid,” said Captain Ranworth, putting his hand upon his friend’s shoulder. “Everything will soon be put to rights, you will see! I’ll go at once and bring all the papers from Northcote’s room, pile them on the desk here, and make a start at sorting them.”

Then Mary Blythe-Headley stepped forward from where she stood beside her father and offered Reid her hand.

“You must be exhausted by all that has happened,” said she. “Let us sit together in the garden for a little while, before the daylight vanishes altogether. I have a great deal of news and other things I wish to tell you, and you, I imagine, have much to tell me.”

“I think it is time for us to make our way back to the village, Watson,” said Holmes to me. “There is no more for us to do here now!”

Outside, in the garden of Oakbrook Hall, Holmes expressed a desire to follow a footpath he had observed earlier, which he thought might offer a route to Topley Cross more direct than the road. It was a pleasant pathway, which passed by field and hedgerow down the hill. The sun was just setting as we left, and behind us the sky was a deep blue and the moon was up. Ahead, the horizon was a glow of reddish-orange, above which, in a turquoise sky, a few fugitive scraps of cloud were tinged pink by the dying sun, and a few late crows were hurrying home to roost. For some time we tramped over the rolling countryside in silence, and it was one of the most memorable walks of my life.

“Such a case as this one,” said Holmes as we passed along the edge of a ploughed field, “never fails to remind me of the old saying, that truth is like water: confine it how you may, it will find a way out.”

“It might have taken somewhat longer to emerge without your efforts in the matter,” I remarked with a chuckle.

“It is kind of you to say so, Watson,” returned Holmes, “but I am conscious sometimes of being, in some mysterious way, but a vessel, a mere conduit down which the truth can pass.”

“I think you do yourself less than justice, Holmes.”

“Well, well, I shall not argue the point. Life is a series of such mysteries, and in solving one, we merely arrive at the next.” Abruptly, my friend stopped and turned to me. “But how is your wound, old man?” he queried. “I really must beg your forgiveness! I have been quite lost in my own reflections, I am afraid. It was unpardonably thoughtless of me to drag you over these fields.”

“Not at all,” I returned. “It is nothing; nothing, at least, that a hot cup of tea at The White Hart will not put right!”

“Good man!” cried my friend with a chuckle. “There is much tragedy in the world, Watson,” he continued after a moment, as we resumed our progress, “and much sorry loss of life, from Maiwand to the Willow Pool. Yet as the night that now creeps over the land quickens our desire for the rising of the sun in the morning, so, perhaps, each dark passage in our lives may teach us to strive always for the light. So, at least, with the help of a merciful Providence, we must hope.”