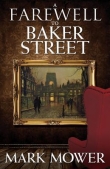

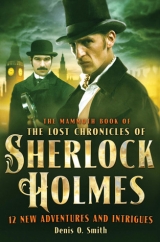

Текст книги "The Mammoth Book of the Lost Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes"

Автор книги: Denis O. Smith

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

CEDRIC, THE EDUCATED LION:

will amaze and amuse you!

THE LAST OPPORTUNITY THIS SEASON

TO SEE

THE FINEST SPECTACLE IN LONDON!

NEAREST STATION: HAMMERSMITH.

“I rather fancy, from your description of the men that these are your abductors,” remarked Holmes to Townsend. “The man with the knives would be this man, Tadeusz, and his immensely strong companion Vigor, ‘the Hammersmith Wonder’. The woman whose charms so struck you might well be this Hippolyta. Indeed, it appears you were only wanting ‘Cedric, the educated lion’ to make up a complete troupe! Have you visited Ostralici’s circus this summer?”

Townsend shook his head. “No,” said he, “but I have heard that it is very good. The horses, especially, are said to be most spectacular.”

“There have been posters advertising the circus outside Paddington station all summer,” I remarked, “and there was an article about it in one of the illustrated papers last week-end, which my wife showed me. Several of the leading performers are, I understand, Polish. The woman who goes under the name of ‘Queen Hippolyta’ is in fact Vera Buclevska, who at one time had a well-known riding act with her sister. She is said to be the finest horsewoman in Europe.”

“But if these are the men who abducted me,” said Townsend in a puzzled tone, “what possible motive could they have had? Why should they seize me in broad daylight in Oxford Street? I have done nothing to them. The whole business is quite pointless!”

“It appears certain,” responded Holmes, “that their kidnapping of you was a mistake. The woman’s reaction when she saw you, and the quarrel that ensued, is clear enough evidence of that, as is the fact that they then deposited you unharmed in Hyde Park. You did not give them your address?”

“They never asked me for it,” replied Townsend, shaking his head.

“And yet you heard them mention ‘Gloucester Terrace’ when they were talking together. They therefore knew the address already, and had quite possibly followed you from there until an opportunity presented itself for them to accost you. You say that your fellow lodger’s name is Smith?”

“Yes, Jacob Smith. I have occasionally seen his post lying on the hall table.”

“There are no other lodgers in the house?”

“No.”

“Then it must be Smith that they were after. You usually leave the house before nine o’clock in the morning, but yesterday you left at ten and encountered Smith on the stair. He appeared about to leave the house until you startled him. The inference is that ten o’clock is his usual time of departure. It seems likely, then, that the kidnappers seized you in the belief that you were he. If that is correct, then it follows that although they know Smith’s address, and something of his daily habits, they do not know him well enough to recognize that they had got the wrong man, and had to wait for ‘Hippolyta’ to inform them forcibly of the fact. What lies behind it all we cannot at present say, but it seems likely that your fellow lodger is in some danger. Having realized their mistake, these people are likely to try again to get their hands on him. We had best call at Gloucester Terrace first to warn him, before attending to the little matter of your cigar case.”

“Of course, the cigar case is not important if Mr Smith is in danger,” said Townsend, “but I am surprised you are so confident of finding it. Why, the house in which they held me might be anywhere in London!”

“When your captors went to bring the woman, they were gone for only a few minutes, and she appeared as if she had hurriedly left her business to come. The inference is that you were being held at no great distance from the circus encampment at Hammersmith.” As Holmes was speaking, he took his hat from the peg and opened the door. “There is no time to lose,” said he, in answer to our surprised expressions. Two minutes later we were in a cab and on our way to Gloucester Terrace.

Despite our haste, however, we were too late. Mr Townsend’s fellow lodger was not in the house, and we were informed that he had had visitors at ten o’clock that morning.

“There were three of them,” the housekeeper informed us: “a very handsome young lady, a tall, thin man with a waxed moustache, and a large, thick-set man.”

“Hippolyta, Tadeusz and Vigor,” said Holmes tersely. “Did Mr Smith leave with his visitors?” he asked the housekeeper.

“That I could not say, sir,” the woman replied, “for they let themselves out, but shortly afterwards, when the maid went up to clear away Mr Smith’s breakfast things, there was no sign of him in his rooms at all.”

“The matter grows serious,” said Holmes as we hurried out to our cab. “We will go at once to Hammersmith.”

“Should we not inform the police?” I suggested.

“It will only delay us unnecessarily,” responded my friend. “We can find a policeman when we need one.”

The traffic was dense, and it took us a good half-hour to reach Hammersmith. The cabbie knew where the circus was camped and took us straight there, but as we stepped from the cab, Holmes groaned with dismay, for all about us was a chaotic scene of activity. Poles and planks were being carried this way and that and it was evident that the circus was being dismantled.

“Of course, the advertisement stated that this was the last week of the season!” cried Holmes, as we threaded our way through the crowds of people and past the stables and animal cages. “The circus is breaking up, and these villains must have believed that they could make good their escape! Let us hope that we are not too late!”

A stout man in a billycock hat appeared to be in charge of one of the gangs of workers, and Holmes asked him where we might find the manager.

“If it’s Captain Ostralici you’re after,” he responded in a gruff tone, “you’ve missed him. He only stayed long enough this morning to supervise the loading of the ’osses, and then he left, along with Miss Buclevska and the others. I’m in charge here now, until everything is cleared away.”

“Where have they gone?”

“That depends who you mean. The ’osses have gone down to Petersfield for the winter, the other animals go tonight, and Captain Ostralici’s party left on the noon train for Dover, bound for Warsaw.”

Holmes consulted his watch as we turned away. “This makes it a little difficult,” said he. “Still, their train will not have reached Dover yet, and if we can convince the police here of the seriousness of the matter, they can wire their colleagues in Kent to prevent Ostralici and the others from boarding the boat.”

As he spoke, he had been glancing quickly round the perimeter of the circus encampment. Now, with a cry of triumph, he directed our attention to a large, dilapidated old house, which stood in the distance, behind a crumbling, ivy-covered brick wall. It had obviously not been occupied for many years, and most of the windows were boarded up. Quickly we made our way across the green, through the open gateway, and round the back of the house, to a yard that was almost choked with brambles and weeds. The lock on the back door had been forced, and we were soon inside and making our way through the deserted building and up the stairs. There, Townsend led the way into a dark and dusty bedroom.

“This is the one,” said he. “Your eyes become accustomed to the gloom after a little while.”

“No sign of Mr Smith, at any rate,” said Holmes, a note of relief in his voice.

We quickly examined the floor by the shuttered window, and had soon found the loose board and lifted it. There, where he had hidden it, was Mr Townsend’s cigar case. As he lifted it up, the diamond in the corner caught the beam of light from the window and sparkled like a tiny star.

“I could not have imagined when I consulted you,” said Townsend, clutching his prize to his bosom, “that you would find it so quickly, Mr Holmes. To speak frankly, I doubted that you would find it at all. You cannot imagine how dear to me this little case is. I shall be forever in your debt. Now, I suppose, my part in this strange affair is at an end.”

“By no means,” Holmes returned quickly. “I should be very much obliged if you would accompany us to Dover, if you feel equal to it, to assist with the identification of these villains and to help us find your fellow lodger, Mr Smith. But first we must call at Scotland Yard.”

Mr Townsend nodded his head in agreement, declaring himself “ready for anything”, and we set off at once. Holmes wired ahead, before we caught a train to Westminster Bridge, and when we arrived at Scotland Yard we were met by the tall, stout figure of Inspector Bradstreet, to whom Holmes quickly explained how matters stood.

“As I understand it, then,” said the policeman, “it seems likely that this gang has hold of Mr Smith. Whether their intention is to smuggle him to the Continent, or to do him some mischief between here and the Channel, we cannot say, but I can certainly ensure that they are not allowed to board the boat until we have had a chance to question them.” So saying, he hurried from the room, but was back again in a few minutes. “It is all arranged,” said he. “The Harbour Police will detain them until we arrive. There is a train from Charing Cross at two-ten, which will get us into Dover before five. The station master has agreed to hold it for us, but will only do so for five minutes, so we must get round there at once!”

We reached the station platform with barely a second to spare, and leapt aboard the train as the guard blew his whistle. Scant minutes later, we were flying through the outlying suburbs, the little houses and gardens all bathed in the golden autumn sunshine.

“It is, of course, possible,” remarked Holmes, “that some harm has already befallen the mysterious Mr Smith. The fact that these people were leaving the country today probably explains why they have acted only in the last twenty-four hours.”

“No doubt they thought they would be beyond our reach before we had discovered what had happened,” agreed Brad-street. “I should very much like to know,” he added, “what their motives might be.”

“From what I have seen of him,” said Townsend, “I should not have said that Mr Smith was a man of any great wealth.”

“I do not think it is money they are after,” said Holmes with a shake of the head. “The fact that your captors summoned ‘Hippolyta’ to see you, and that she then appeared to berate them for the mistake they had made, suggests that the issue may be something personal to that lady herself. It is, however, pointless to speculate further in the absence of data,” he continued, leaning back in his seat and filling his pipe. “We shall be able to question the scoundrels directly in a little while.”

The sky had clouded over by the time we reached the coast, and as we alighted from the train a strong salt breeze was blowing off the sea. Up above, against the leaden sky, crowds of raucous, wind-buffeted seagulls wheeled and dived in endless spirals. We hurried to the harbour master’s office, where we were met by Superintendent Waldron of the Dover Harbour Police.

“I have them here,” said he. “They were not a difficult group to recognize,” he added with a chuckle. “The big fellow looked inclined to give us a bit of trouble at first, but the woman said something to him and he quietened down soon enough. I’ll have them brought up now.”

The harbour outside the window was crowded with shipping, and I was gazing upon this busy scene, where a forest of masts and spars, flags and rigging thronged the sky, when the door was opened and the fugitives were led in. The officer in charge read out their names from a sheet of paper. There was Captain Alexei Ostralici, as I had seen him depicted on posters, the lines about his large, gentle eyes bespeaking fatigue at the end of a strenuous season. Next to him stood Tadeusz Grigorski, otherwise known as “the Great Tadeusz”, his waxed moustache aquiver at the indignity of his situation. By his side was an enormous man, with the chest and limbs of a Hercules. He was named as Viktor Kosciukiewicz, but was instantly recognizable as “Vigor, the Hammersmith Wonder”. Last of all, and standing a little apart from the others, was a graceful, delicately featured woman, elegantly attired in a dark blue travelling costume. Named as Miss Vera Buclevska, she would be more readily known to the general public as “Queen Hippolyta of the Circus Ring”.

It is an odd and unsettling effect that a woman can sometimes have upon a gathering. To those who have experienced this, I need say nothing. To those who have not, no words of mine can adequately convey my meaning. I am not speaking simply of beauty, far less of ordinary prettiness, but of something else, akin in its effects to a mysterious species of magnetism, but which is, in truth, quite indefinable. Such was the effect Miss Buclevska appeared to have upon the harbour master’s office at Dover that afternoon, for upon her entrance an odd silence seemed to fall upon the room, and for a moment no one spoke.

“Well?” said Miss Buclevska herself at length, in strongly accented English, looking at each of us in turn.

Inspector Bradstreet cleared his throat. “This gentleman,” said he, indicating Mr Townsend, “has laid a serious charge against three of you, that you kidnapped and held him prisoner for several hours yesterday. What have you to say to this charge?”

Miss Buclevska glanced quickly at her companions, then turned to face us once more.

“I will speak for all,” said she softly. “These men acted for my sake. We deeply regret what occurred. The gentleman you indicate,” she continued, looking at Townsend, “has every right to feel aggrieved, but we meant him no harm. It was a most unfortunate mistake, and we are sorry for it.”

“You meant Mr Townsend no harm,” interrupted Holmes, “only because your friends in fact intended to kidnap his fellow lodger, Jacob Smith.”

“His name is not Smith,” said she, her eyes suddenly flashing fire. “His true name is Jakob Schmidt, for he is a German. But, yes, they did intend to kidnap him, as you say. I did not ask them to do it, but they believed I wished it. He is an evil man, but a man with a silver tongue. Throughout Brandenburg his name is reviled and men spit when they hear it. Some years ago he announced a great scheme to build new docks on the banks of the River Havel, north-west of Potsdam. Success was assured, so he declared. Enormous amounts of money were subscribed. Many people gave their life savings to the project. Alas, all his assurances proved worthless. The entire scheme collapsed, and all those who had subscribed money were ruined. All, that is, save one man. That man, as you will guess, was Herr Schmidt himself. The crash of his company left him a surprisingly wealthy man. Of course, there was a public outcry and enquiries and investigations followed, but nothing could be done about it, for Schmidt had acted entirely within the law. He was a lawyer himself, and knew how to arrange such things in his own favour. When the enterprise collapsed, with scarcely a penny to its name, much of the missing money was, in truth, in Schmidt’s own hands, but the law could do nothing.”

“You lost money in Schmidt’s scheme?” queried Holmes. “This is the connection between you?”

“I lost a little,” said she. “No one in Brandenburg at that time escaped unscathed from Schmidt’s foul and dishonest schemes. But that is not what makes me bitter. I tell you these things only so you know the type of man he is. My own unfortunate connection with that evil devil is a more personal one.

“Some years ago, my younger sister Krystina and I had a riding act together. You may have heard of the Buclevska Sisters. We performed in Warsaw, Vienna, Budapest and many other places, and had, I may say, a considerable renown. One summer we had been performing in Berlin and were taking a short holiday near Potsdam. This was at the time that Jakob Schmidt’s local celebrity was at its height, before the smash came. We met socially, and Herr Schmidt’s silver tongue turned Krystina’s head. I warned her against him, for even then I did not trust him, but she would not listen. Soon he had persuaded her to go away with him to his summer home in the south, and she became estranged from her family and from her friends. All were shocked and distressed at this, but what could be done? So much had he twisted her to his wishes that she would not even speak to me, Vera, her sister.

“Of course, you can imagine the rest. When the financial smash came, Schmidt left the district, and cast Krystina off without a thought, like an old shoe. All the promises he had made to her proved as worthless as the promises he had made to the people of Potsdam. Presently, my sister crept back home, but something within her had died. We welcomed her back without a word of censure, but her own heartbreak and shame were destroying her. She did not last six months, gentlemen. If anyone tells you that a broken heart cannot kill, do not believe them, for I have seen it happen. Krystina pined away, became very ill and, one fine spring morning, passed beyond all mortal help. That is the connection between Herr Schmidt and myself about which you enquired.”

Vera Buclevska finished speaking and stood facing us defiantly, her cheeks flushed and her lip trembling.

“You wished to see Schmidt, then,” said Holmes after a moment.

She nodded her head and passed her hand across her brow. “That is so,” she replied. “I learned that he was living in London. I wrote to him twice, but received no reply. Then my friends here, knowing how the matter was distressing me and affecting my performance, took it upon themselves to bring him forcibly to see me. Alas! They knew nothing of Schmidt other than what I had told them, and they seized the wrong man, as you know.”

“Where is Schmidt now?” asked Holmes.

“Now?” the lady repeated. “I do not know, and nor do I care!”

Holmes frowned. “But you called upon him this morning. We had your description from his housekeeper.”

“That is so. The miserable coward sat trembling as we spoke. I accused him of the evil he had done to Krystina and to the poor people of Brandenburg. To all my remarks he said nothing, expressing neither sorrow nor remorse. On his face was only fear. Eventually Tadeusz pressed upon me that I was wasting my time, and was succeeding only in making myself more miserable. Besides, I could see for myself that Schmidt was ill – he had declined dreadfully since the last time I saw him – and it was clear that all his dishonesty and scheming had brought him no happiness. We therefore withdrew. My only hope now is that I never see that odious reptile again as long as God permits me to live.”

“You did not force him to go anywhere with you?”

“Certainly not. I could not bear to remain in his company a moment longer.”

“But he has disappeared.”

Miss Buclevska’s mouth fell open in surprise, and it was clear that this news was unexpected.

“It was feared that some harm had befallen him,” continued Holmes.

“Not at our hands,” said she.

Bradstreet cleared his throat again. “This makes it rather difficult,” said he. “I shall have to wire to London for further enquiries to be made. In the meantime—”

He was interrupted by a knock at the door, and a uniformed official entered.

“I’m to tell you that the boat must leave in ten minutes,” said he, “with or without the Ostralici party. There is also a message for Inspector Bradstreet,” he added, holding out a thin sheet of paper.

The policeman took the sheet and read it, then he looked up with a smile.

“It is from one of my colleagues,” said he. “He considered it would be of interest to me. Jakob Schmidt walked into Paddington Green Police Station this afternoon at three o’clock, demanding protection against a gang of foreigners who he said were terrorizing him. Apparently he had been hiding in the British Museum all day!”

There was perceptible relief on every face there. We had all, I think, been moved by Vera Buclevska’s story and were glad to have her statement confirmed.

Captain Ostralici smiled wearily. “So,” said he. “Matters are resolved. Are we permitted to leave now?”

Inspector Bradstreet hesitated and looked at Mr Townsend. “A serious criminal offence has been committed,” said he at length, “whatever the reasons for it may have been. Mr Townsend was forcibly kidnapped yesterday morning and held against his will.”

“That doesn’t matter,” said Townsend abruptly in a quiet voice, looking a little embarrassed to be the centre of attention as we turned to hear what he would say. “I wasn’t harmed,” he continued after a moment. “I understand what lay behind it now, and I accept the apology that has been made to me. I would rather not press charges, Inspector.”

Bradstreet raised his eyebrow. “Very well, then,” said he, addressing Captain Ostralici and his friends. “The matter is closed, and you are free to go.”

“I’ll arrange to have your luggage put aboard at once,” said the harbour official, and hurried from the room.

Captain Ostralici stepped forward, clicked his heels and shook Townsend’s hand. “Sir, you are a gentleman,” said he with a little bow. “You may like to know that Miss Buclevska has lately done me the honour of consenting to be my wife. We are to be married in Warsaw next month. Your generosity in this matter has removed the one dark cloud that hung over our preparations.” Vigor and Tadeusz then shook hands with Townsend, and finally Miss Buclevska took his hand in hers.

“You are a very kind and generous man, Mr Townsend,” said she softly, “and deserve happiness. We return in the spring,” she added after a moment, “and I hope to see you at the circus then.” Townsend, who appeared to have stopped breathing, merely smiled and nodded as she released his hand and turned to follow her companions from the room.

“Capital!” cried Holmes in a gay tone, clapping his hands together. “This calls for a celebration, and as we appear to have missed a meal today, I suggest we take advantage of our situation and sample the fare at one of the local fish restaurants!”

There was general assent to this suggestion and, five minutes later, Holmes, Bradstreet, Townsend and I found ourselves on the upper floor of a large restaurant near the harbour, where a balcony looked out across the sea. The clouds were beginning to break up again and blue sky was showing through.

“There goes the ship!” cried Holmes all at once, and we watched as the channel packet slipped slowly out of the harbour, carrying those singular circus folk upon their long journey to the east. Slowly the vessel drew away from the shore, until it was a mere dot upon the broad expanse of sea.

“What a very strange affair!” remarked Bradstreet in a thoughtful voice as our meal was served.

“A singular business, indeed!” concurred Holmes with a chuckle. “I should not have missed it for the world! For you and me, Bradstreet, it has meant an afternoon at the seaside, away from the smoky city, for Mr Townsend, the return of his precious cigar case, and a story his friends will scarcely credit, and for Dr Watson, another entry in that catalogue of the mysterious and recherché, which he so delights in compiling!”