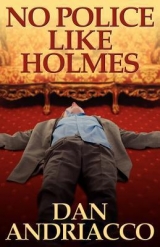

Текст книги "No Police Like Holmes: Introducing Sebastian McCabe"

Автор книги: Dan Andriacco

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter Thirteen – I Can’t Believe This

Listening to Professor Malcolm Whippet of Licking Falls State College, the first speaker of the afternoon session, was like suffering a Chinese water torture of words.

Whippet was a frail figure in his late sixties, medium height, thin, with a high forehead, fringes of gray hair, age spots on his head and hands, and gray-green eyes. He was so slight he hardly seemed to be there at all.

Whenever he had to turn the pages of the paper he was reading, he stopped his nasal monotone to lick his fingers. After a few introductory comments (“Let us begin with the obvious – Sherlock Holmes was an American”), Professor Whippet’s presentation on “Nick Carter, Alias Sherlock Holmes” turned out to be a pastiche, an imitation Holmes story. Whippet lacked, however, a few tools of the storyteller’s art, such as a sense of pace, an ear for dialogue, and a rudimentary notion of plot. Also, he couldn’t write.

“‘Yes, my faithful Watson, it is quite so!’” he read. “‘All these years I have concealed my true identity even from you. I am indeed Nicholas Carter, the famous American detective!’”

Putting a hand over my mouth to stifle an impolite sound, I looked around the room to see how this was going over with the Sherlockian set. A lot of people were shifting in their seats, including Lynda and Matheson. They were still sitting next to each other and Lynda wasn’t sending any lovesick looks my way, contrary to my sister’s observation.

Mac had deposited himself in a wingback chair next to me at the back of the room. I leaned over to tell him, “I can’t believe this. How do this guy’s students stand it?”

“Students?” Mac repeated with dismay. He raised an eyebrow. “Surely you jest. Professor Whippet has tenure, not students. Do not demean the man’s achievements, Jefferson. It takes considerable talent to make Sherlock Holmes this boring. I had no idea he had it in him.”

Whippet droned on. I looked at my watch: two-eleven. When it seemed like half an hour had passed, I looked at it again: two-fourteen. Would it never end? It did, finally, but not until the speaker had run five minutes over his allotted time and brought into his story Mycroft Holmes (revealed as one of Nick Carter’s operatives), Grover Cleveland, Fu-Manchu, Jack the Ripper, Count Dracula, Oscar Wilde, the Prince of Wales, and Tinker Bell.

When the concluding cliché had been uttered, the applause of a grateful crowd shook the room. Nobody called for more.

Next up on the program was a man Mac introduced to my surprise as Lars Jenson, the most prominent Swedish publisher of the Sherlock Holmes stories. I’d known he was coming, of course – from a conference in New York, not directly from Sweden. But I had never connected his name with the stoop-shouldered fellow from the rare book room, the one with the whitish-blond hair hanging over one eye à la Carl Sandburg. Dressed in a double-breasted blue suit, pink shirt, wide paisley tie, and socks with little clock designs on them, he didn’t look like my idea of a publisher.

When he opened his mouth, Jenson sounded like the Swedish Chef on The Muppet Show. Approximately every other word started with either a “y” or a “v” sound, which made it hard to figure out what he was saying. There was something about Sherlock Holmes helping the King of Scandinavia on two occasions, and Holmes and Watson visiting Norway at the end of one of their adventures. And Holmes, if I caught it right, once adopted the guise of a Norwegian explorer. But don’t expect me to give you quotes.

All the while he talked, Jenson kept playing with a pair of horn-rimmed glasses. He’d put them on, yank them off, put them on, yank them off. There seemed no rhyme or reason to it, since he didn’t use the glasses to read from notes. For awhile I was fascinated, trying to figure out a pattern. But it started giving me the heebie-jeebies until finally I couldn’t stand it anymore and I left.

Out in the corridor, haunted by that Swedish Chef voice coming over the loudspeaker, I flipped out my iPhone. After posting a quick tweet (“Last two speakers at Doyle-Holmes colloquium truly unbelievable”), I called a certain cell phone number. Graham Bentley Post answered with his names – all three of them – on the third ring.

“This is Thomas Jefferson Cody,” I informed him, not to be outdone in the multiple names department. “I’m calling from St. Benignus College and I’d like to talk to you about the Woollcott Chalmers Collection.”

“Indeed?” His voice turned warmer, say three degrees. “I have already had some discussions of that nature with Mr. Pfannenstiel. They have not been fruitful.”

“I know,” I said. “When and where can we meet?”

He suggested six-thirty and dinner at the restaurant in the Winfield, which is top-notch, but I planned to stick with the colloquium right through the seven o’clock banquet in the President’s Dining Room. Post had an appointment at a private home on Everly Street until after five o’clock, so we agreed to meet at five-thirty at the nearby main branch of the Sussex County Public Library.

“I hope you’ll have some news for me, Mr. Cody,” Post said.

“That goes double,” I assured him.

As I disconnected, I wondered why Post hadn’t even mentioned the theft last night. It seemed a remarkable oversight – unless he’d been deliberately avoiding the subject.

My spot on the couch at the back of the Hearth Room had been swiped by a man in a string tie, so I slipped into a chair in the last row. I was in front of Mac and lined up almost exactly behind Lynda and Matheson, who leaned over to whisper things to her with alarming frequency – alarming to me, anyway.

Dr. Queensbury had the lectern, discussing Sherlock Holmes and cocaine. Still wearing the deerstalker cap, he paced and postured like the great detective himself as he quoted alternatively from the Holmes stories and from the British medical journals of the day. I wrote down some of his more memorable points:

“Watson mentions Holmes’s use of cocaine only five times, and all of them in stories appearing between 1890 and 1893.”

“In 1890 cocaine was still considered a therapeutic agent. It was a non-prescription drug. Not until the middle of the decade did Freud reject it.

“It has been questioned, however, whether Holmes really used cocaine at all. Perhaps he was just having Watson on.”

Queensbury’s talk had at least one outstanding virtue: It was only about fifteen minutes long. Even after he took questions from the floor the program was running ahead of schedule. Queensbury sat down, amid applause, and there was an awkward gap when he wasn’t replaced at the lectern. I looked behind me but the master of ceremonies, Mac, was no longer there either. Finally, my sister Kate stood up and announced that it was time for an “interval” or break between sessions.

The flow of the crowd went in two directions – either out the doors (heading for such amenities as coffee, the restroom, or a place to smoke outside) or toward the back of the room, where the bald man was selling books and what I would call trinkets.

As I stood up to stretch my longish legs, I heard somebody behind me at the book table say:

“I have that book!”

“British or American edition?” another voice asked.

“Both.”

Stirring stuff, but where in the world was Mac? I wanted to tell him about my appointment with Graham Bentley Post. Queensbury’s talk coming up short obviously had caught Mac off guard. Looking around the room I still didn’t see his huge form.

“Jeff!”

I sure liked that voice. Renata Chalmers, flashing that thousand-watt smile at me, nudged her way through some of the reveling Sherlockians until she stood at my side. She pushed a wild strand of black hair out of her eye and stuck her hands into the pockets of her dress-for-success suit.

“What do you hear from the campus police?”

“Nothing worth repeating.”

“No theories at all?”

“Oh, there are theories galore,” I said, lowering my voice, “but not from the cops.”

“Really?” Oh, that smile. “Please tell me. I just love theories.”

I shook my head. “No way am I going to name names. I could be slandering somebody.”

And considering who one of my hot suspects was, a legal battle was the last thing I wanted.

I could have sworn Renata was about to resort to feminine wiles – something about the man-eating look in her brown eyes as she opened her mouth – but just then her husband limped by and she buttoned up.

“Hello, Cody,” he said, giving me one of the man-to-man slaps on the arm that I’ve always hated. “The program seems to be going well despite last night’s unfortunate curtain-raiser.”

He leaned on his cane and we exchanged pleasantries. I told Chalmers how much I enjoyed his morning talk. He said he was quite pleased with the way the Chalmers Collection looked in our library. I assured him that Campus Security was doing everything possible to recover the rest of the collection. After a minute or two of that, the Chalmerses left to powder their noses or whatever and I was left pondering the books for sale. Some were old and possibly rare, while others were new or even paperback. How could there be so much written about one thin guy with abominable taste in headgear?

The bald bookseller smiled, showing a gold tooth, and pointed to one slim volume with a garish cover. “There’s a new one,” he said helpfully.

I picked up the book and checked out the title: The Adventure of the Unique ‘Hamlet.’

“It’s actually an old story, of course, the famous Vincent Starrett pastiche, but a new edition with some cool illustrations,” the dealer said. “You’ve probably read it.”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Well, it’s about a bibliophile who asks Holmes to solve the theft of his rare edition of Hamlet.”

“How timely,” I said dryly.

The bookman nodded. “In this story the client did it himself – to hide the fact that the supposedly rare volume was a fake.”

From behind me a familiar voice said: “An excellent volume you have there, Jefferson! It was one of the early pastiches, and it remains one of the finest.”

I whirled on my brother-in-law.“I set up an interview with Post. Where the hell have you been?”

“I the hell have been conversing with Lieutenant Decker, asking him the key questions that will solve this elementary case.”

“Oh, yeah? Such as?”

He shook his hairy head. “On that point I remain coy, Jefferson. Perhaps my little idea is all wrong and you would think less of me later.”

“You? Wrong?” I forced out what I hoped was an obviously faked chuckle.

“Yes, the notion is risible, is it not?” Mac gestured with the unlit cigar in his hand. “Let us say, then, that I will not answer that question because no good amateur sleuth would – not Ellery Queen, not Amelia Peabody, not Damon-”

“Oh, just stuff it, Mac. You can’t hand me that crap.”

“I just did, old boy.”

The lights in the Hearth Room flicked off, on, off, on. Somebody was trying to tell us something.

“Not another word, Jefferson,” Mac said. “We shall have to recommence this verbal ballet later. The interval is over.”

Chapter Fourteen – Master of Disguise

Barry Landers was a student of Mac’s, which put his most likely age between eighteen and twenty-one. Wearing jeans and a yellow and black Sherlock Holmes T-shirt as he stood at the lectern, he looked even younger. He was short, overweight, baby-faced.

But he talked with confidence and authority, using a vocabulary that was closer to Sebastian McCabe than something he might have picked up from watching teen-oriented television.

“Sherlock Holmes is, to use an overused phrase, a ‘master of disguise,’ ” he said. “We’re not only told this in the canon, we’re shown it. At different times Holmes appears as a common loafer, a drunken groom, the Irish-American Altamont, the rakish young plumber Escott, a French workman, an Italian priest, a Non-conformist clergyman, Captain Basil, an opium smoker, the explorer Sigerson, an elderly bookseller, and an old woman.”

Disguise, yet. And Mac sat there, back at the front of the room now, hanging on every word as if he could disguise himself as, say, a “rakish young plumber.” Was he really on to something with whatever he had asked Decker or was it just B.S.? A toss-up. With Mac you could never tell. He was, after all, a professor.

“What is interesting to note,” Barry Landers went on as I inched my way toward the door, “is that Holmes himself is more than once fooled by disguise. In A Study in Scarlet, Jefferson Hope’s friend poses as an older woman, causing Holmes to say later, ‘We were old women to be taken in.’ And in another famous sex reversal, Irene Adler dresses as a man the evening she walks by Holmes in Baker Street and says, ‘Good-night, Mr. Sherlock Holmes.’ ”

By this time I was in the corridor, pulling out my phone. I called Decker.

“You again?” he grumped.

“Show some gratitude. I saved your butt from a TV crew today, now I hear you’re talking about the crime to Mac.”

“He caught me by surprise.” Decker did not sound pleased.

“What did he ask you?”

“A bunch of stuff about keys to the room where the books were stolen,” Decker said. “Things like, ‘How many are there?’ and ‘Who has them?’ Pretty basic.”

“So what did you tell him?”

“Running down the keys wasn’t exactly brain surgery,” Decker said. “We did that before I went to bed this morning. Call it five keys altogether, counting the masters that open every door in Muckerheide. Nick Caruso and Bobby Deere each have masters they carry all the time.” Caruso runs the Center by day; Deere sleeps there at night. “Campus Security has another master that’s picked up by the guard at the beginning of his shift. The Muckerheide Center office has two individual keys to Hearth Room C. One was safely locked away there last night; Deere showed it to us. The other was on loan to Gene Pfannenstiel, who recklessly gave it out-”

“-to Sebastian McCabe,” I finished. “So every key is accounted for?”

“Tighter than a drum. Pfannenstiel swears up and down he never had his key out of his hands until he slipped it to McCabe around seven last night. And the one that was still in the Center office hadn’t been signed out all day.”

“And what did Mac say to that?”

“He wanted to know if it was shiny. I told him I didn’t know.”

“Shiny? What’s that supposed to mean?” I demanded.

“Damned if I know. He’s your brother-in-law.”

“Don’t rub it in. Did he say anything else?”

“Yeah. He said I should find out, and that the key he used last night – the one I made him turn in to me – wasn’t shiny.”

Chapter Fifteen – “Women Are Never to Be Trusted”

I was supposed to meet Graham Bentley Post at five-thirty. Eager as I was to be on with it, my watch told me that was still forty-five minutes away. I returned to the Hearth Room, standing just inside the door at the front where, for a change, I could scan the faces of the crowd instead of bad haircuts.

My sister was at the lectern.

“... and Holmes himself repeatedly misstates his own posture toward the female of the species. In The Sign of Four, for example, he says that ‘love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry myself lest I bias my judgment.’ Holmes implies here a calculated neutrality with regard to women. This is patently false. Elsewhere in the same book Holmes tells the good Watson, ‘women are never to be trusted – not the best of them.’ That is hardly a neutral attitude.”

Hugh Matheson slid his arm across the back of Lynda’s chair as he leaned forward to whisper some sweet nothing. Pained, I looked around the room, making a little game out of seeing how many faces I recognized. There were quite a few: Kane, Queensbury, Crocker, Nakamora, the ineffable Professor Whippet...

“And in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia,’ ” Kate continued, “Watson reports that Holmes ‘never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer.’ Does that sound like a man purged of all emotions toward the opposite sex? On the contrary, Holmes displays quite a strong emotion – a negative one. Was he, then, a born misogynist as some would have us believe – or even a homosexual? I submit that the opposite is true. At some point in his unrecorded past Sherlock Holmes loved well but not wisely. He was, in short, ‘burned.’”

Now there was something I could relate to, I thought bitterly.

Kate went on to talk about Irene Adler (“the woman”), Mary Sutherland, Violet Hunter, and other strong females in the canon. She attributed their dynamic portrayals to the influence of Arthur Conan Doyle’s own strong-willed mother. Dr. Queensbury was just rising, apparently to object to this gratuitous reference to Conan Doyle, when I checked my watch again and saw that nearly half an hour had flown by and Kate’s talk was running over. If I didn’t make tracks I’d keep the man from the Library of Popular Culture waiting.

My brother-in-law, sitting near the lectern just across from where I was standing, seemed too engaged in the looming confrontation between his wife and Queensbury to notice my departure. In the corridor I thought I had gotten away clean until one of the voices I know best called after me. “Jeff!”

Lynda Teal.

I retracted my foot from the down escalator, almost slipping in the process.

For once Lynda looked slightly less than perfect, even to me. One or two strands of honey-colored hair were out of place and her blouse was disheveled. She was chewing gum. Still, I found myself having to fight off thoughts of a romantic and even biological nature.

“Where are you sneaking off to?” she demanded.

“The men’s room,” I said, the first thing that came into my head.

“Baloney. You don’t have to go downstairs for a john. Look, I saw you and Mac conniving during the last break. You two are up to something and I want to know what it is. It’s something about those stolen books, right?”

“So it’s not my rugged good looks or my charming personality that has you so interested in my activities all of a sudden. You’re just chasing a story.”

“Well, yeah. It’s what I do.” She leaned against the escalator. “I’m a journalist.”As if I needed reminding.

I shook my head sadly. “And to think we used to have such good times together.”

“Didn’t we, Jeff? And always I’ll remember. Now, what’s Mac got you doing this time?”

I snorted. “This is my game plan, not Mac’s.”

“Okay. What is it, then – a clue, a witness, a suspect?”

“Something like that. I’m supposed to meet a guy in-” I looked at my watch. “Damn. Ten minutes. I’ll never make it.”

“I’ll give you a ride. My car’ll get you wherever you’re going a lot faster than that bicycle of yours. You are still riding the bike everywhere you don’t walk, aren’t you?”

“Not everywhere. I still have the Beetle for trips over ten miles.” Even to me that sounded lame. I hurried on. “This is a solo venture, Lynda. Besides, you wouldn’t want to leave the great Hugh Matheson all alone, would you?”

“He’s got his ego to keep him company.”

“You didn’t seem to mind while you were sitting with him all day.”

“I was being polite.”

“Polite? He was whispering in your ear!”

“Yeah, mostly about his favorite subject – him.”

“This has been great, Lynda, but I really-”

“You have less time now than you did five minutes ago. How about that ride?”

The doors of the Hearth Room sprang open and people started pouring out. Matheson was near the head of the herd, busy bending Judge Crocker’s ear.

“Okay, okay,” I said, making the snap decision that put me right in the thick of the mess that followed. “Let’s just get out of here.”

We ran down the escalator to the main level of Muckerheide Center and out a side door to the campus street where Lynda’s yellow Mustang was illegally parked.

As soon as I got into the car, I noticed something different.

“Hey, it doesn’t smell like an ashtray anymore,” I said.

“I gave up smoking and took up running,” Lynda explained as she set her camera and purse on the floor behind the driver’s seat.

I stared at her. She studiously ignored me.

“That’s great,” I said finally. “Good for you. Why didn’t you do that all those years I was nagging you to?”

“Because you were nagging me to. Now, who is this guy you’re supposed to meet?”

While she drove the car and chewed a fresh stick of gum, I filled her in on Graham Bentley Post and his obsession to possess the Woollcott Chalmers Collection for his museum. By the time we reached the Sussex County Library, she knew as much about Post as I did.

The main branch happens to be on Mulberry Street, not Main. It’s an Andrew Carnegie library, a brick and stone structure built more than a hundred years ago and seemingly good for at least a hundred more.

From several blocks away I spotted the man pacing in front of the broad front steps. He was in his early fifties, medium height and build, with thick black hair, a gray mustache, and the chiseled features of a comic book superhero. Lynda parked in front of the fire hydrant and I hopped out.

“Thanks for the ride,” I told Lynda.

“Oh, no, you don’t. I’m not just your damned chauffeur.”

She got out of the car and scrambled after me. There was nothing I could do without creating a scene in front of Graham Bentley Post, assuming it was he.

“Mr. Post?” I said, approaching him with an extended hand. “I’m Thomas Jefferson Cody.”

Post was wearing a tailored blue suit without a single loose threat. He glanced at the slightly battered Mustang and then at me as if he doubted my statement, but he shook my hand anyway. I introduced Lynda as my associate.

“Partner,” she said firmly. Hey, I like the sound of that! Too bad you don’t really mean it; not the way I’d like.

Post skipped the small talk. “You are late, Mr. Cody. I can only trust that your arrival will prove worth waiting for. Let me be succinct: What kind of a deal can we cut that will put the Chalmers Collection into my hands?”

“We’re not-” Lynda began.

“We’re not sure what you have in mind,” I interrupted. “The college can never sell the Collection, of course. It was a gift.”

“Perhaps not,” Post conceded, fingering his mustache, “but with the right inducement – perhaps the promise of naming a small edifice on campus in his honor – Mr. Chalmers might be persuaded to withdraw his gift and sell it to the Library of Popular Culture at a handsome price.”

“And what would be in that for the college?” I asked.

“I believe I could arrange for another collection to be donated to St. Benignus, one with greater prestige and monetary value but of less interest to my institution.”

“Quite a scenario,” I said. “Machiavelli would be green with envy. You should bounce the idea off of our provost.”

Post looked at me as if he had smelled something bad and I was it. “You have no authority to negotiate?” “None.”

“Then you have wasted my time. We have nothing to discuss.” He started to walk away.

“I was hoping you could tell me – us – a little about the market for those parts of the collection that were stolen last night,” I called after him.

That stopped him cold. “Stolen? What the devil are you talking about?”

“Didn’t you read about it in the local paper this morning?” Lynda asked.

“I only read the New York Times and I find it appalling that I was unable to purchase a copy at my hotel this morning.”

While Lynda looked daggers at the blowhard, fuming silently, I told Post what had been taken.

“Virtually priceless,” Post gasped. “Of course they have a very high monetary value, hundreds of thousands of dollars or more, but that is quite beside the point. Those are one-of-a-kind items – and stolen right out from under your nose. I assure you nothing like that could ever happen at the Library of Popular Culture!”

“I bet you can’t wait to give Chalmers the same assurance,” Lynda said. “You’d probably even pay for some legal talent to help him withdraw his donation. Then he could give the collection to an institution where it would be safe – yours, for example.”

“That is... preposterous,” Post sputtered. “It would be highly unethical for us to take advantage of this unfortunate situation.”

Lynda snorted. “That’s not the worst thing you might be suspected of before this is all over.”

Post’s jaw obeyed the law of gravity. He fixed Lynda with eyes of ice. “Are you daring to imply that I might be connected in any way with this criminal activity?”

“She’s saying some people might think so,” I interpreted, trying to unruffled his feathers a bit. “It’s awfully convenient that you just happened to be in Erin the day that stuff was stolen.”

“I have a perfectly good reason for being in this insufferable little burg,” Post said.

After an awkward pause, I prodded him: “Care to tell us what it is?”

“No, I would not! It’s a highly confidential matter, as many of our acquisitions are.”

“I can appreciate that,” I said with what I hoped was a gracious nod.“But I’m sort of working with Campus Security in this matter, and I’m sure it would help them to rule you out of any possible involvement if you’d reveal why you’re in town.”

“No.”

“I’m just afraid that if Campus Security calls you in for an interview the press might get wind of it,” I said. I was playing good cop/bad cop against the hypothetical media. “You know how they are,” Lynda chimed in.

“Oh, all right, then,” Post snapped. “But only if you agree to keep this strictly confidential.” We agreed, although I could read the reluctance in Lynda’s eyes as if it were a newspaper headline. She was agreeing to go off the record without the slightest idea of what she was going to hear. “I am in Erin negotiating with a man named Jaspers to acquire the largest privately held collection of Harvey Comics, some issues going back to the beginnings of the company in 1940.”

The smug look on his face told me this was something special, but I didn’t get it. I mean, everybody knows Superman. Spider-Man and Batman I’d read as a kid. X-Men I was familiar with from the movies. But who was Harvey, other than an invisible bunny in an old movie?

“Harvey Comics is Casper the Friendly Ghost,” Post explained, “as well as Richie Rich, Baby Huey, Little Audrey – virtually a treasure house of popular culture.”

It was the mission of the Library of Popular Culture to acquire popular forms of literature for public display and for the use of scholars, Post explained. In pursuit of that mission he’d been trying for years to convince Alfred Jaspers, Sr., to sell his Harvey Comics collection, but without success. Jaspers had died last fall, however, and his son was willing to cash out. The younger Jaspers had invited Post to Erin to discuss the price on Friday. The bargaining was hard and carried over to today, when a deal was struck.

The story seemed plausible and checkable. Post did have a good reason for being in Erin other than the presence of the Chalmers Collection. He readily admitted, however, that he had visited Gene Pfannenstiel on Friday – unaware that the young man had no bargaining authority – before keeping his appointment with Jaspers.

“We have tens of thousands of comics at the Library of Popular Culture, but little Sherlockiana,” Post said. “It would be a tremendous coup to fill that gap by acquiring one of the largest and most prestigious Sherlock Holmes collections in private hands.”

“What you’re saying is, you were hungry,” Lynda pointed out. “So hungry you weren’t going to give up even after Chalmers had decided on his donation to the college. Who knew that?”

Post shrugged. “Assorted bibliophiles, I suppose. Word gets around. Why?”

“Because no ordinary thief took that stuff in hopes of fencing it,” I said, catching her reasoning right away. “It was either a Sherlockian who wanted to gloat over the books in private or somebody who knew where the market was for things like that. And it looks like you’re the market.”

Post drew himself up in a dignified posture reminiscent of the ramrod-straight Woollcott Chalmers. “I am not a receiver of stolen goods, Mr. Cody!”

“Of course not,” I agreed, visions of a slander suit dancing in my head. “But please get in touch with me or with Lieutenant Decker of our Campus Security if you even suspect that someone is trying approach you with those books.” I gave him my card.

“You may be certain that I will do so,” Post said stiffly, without a glance at the card.

He carried his injured dignity away in a late model BMW, midnight blue.

“What do you think?” I asked as he drove off.

Lynda shook her honey-colored curls all over the place. “No way he’s the thief – he’d be too afraid of getting lint on his suit. And stolen goods would be no good to his library-cum-museum anyway because they couldn’t be displayed or made available to scholars. A professional thief would know that, so the idea that somebody took the stuff to sell to Post doesn’t wash, either.”

We climbed into the Mustang. It was six o’clock and we’d spent nearly half an hour going nowhere with Post.

A collector as thief still made the most sense – somebody like Hugh Matheson, Lynda’s newfound friend. But I didn’t say that. I didn’t say much at all until Lynda pulled the Mustang behind Muckerheide Center, right where my bike was parked. She left the motor running.

“You aren’t staying for the banquet?” I asked, my hand on the door. Maybe that was wishful thinking – because if she were coming to the banquet, she probably wouldn’t be sitting alone.

“I’m coming back for it,” Lynda said, adjusting the rear-view mirror. “First I’m going home to play with my hair a little, change my clothes.”

“You look fine to me.”

“Thank you, but Victorian dress is optional and I plan to take the option.”

“You could wear that frilly thing you had on at that Halloween party two years ago. Remember the moon and the music and-”

“Jeff,” she cut in, “the cocktail hour begins in half an hour. I’d better go.”

I sighed. “It’s been good to be around you again. Whatever happened to us, Lynda?”

“You smothered me, Jeff, that’s all. You were domineering and bossy and every other word that describes a man who wanted to run my life like it was his own. I wasn’t born to be a trained pet. And did I ever tell you that you’re also jealous and stubborn?”

“Frequently.” Maybe I shouldn’t have asked that question. “But come on, now, you like me anyway, don’t you – at least a little?” I was trying to keep the mood light because I didn’t want to leave her on down note.