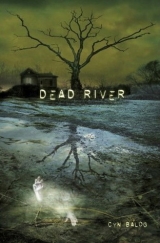

Текст книги "Dead River"

Автор книги: Cyn Balog

Соавторы: Cyn Balog

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

Chapter Fourteen

Ten minutes later, Hugo saunters out of the downstairs bathroom, scratching his backside. He looks pretty okay for someone who just spent hours worshipping at the porcelain shrine. He has a rolled-up Sports Illustrated and is whistling.

I expect to smell something disgusting coming from the open door, but I can’t make anything out. “Did you clean in there?” I ask.

He jumps sky high, like a cartoon character that has stuck its finger in an electric socket. “What the hell are you doing here?”

I don’t answer. “You can open a window, at least. And there’s some 409 under the kitchen sink.” I march over to the bathroom to inspect it, knowing it’ll be gross. I can already tell from the way Hugo threw his McDonald’s hamburger wrappers all over Monster that he isn’t the cleanest person on earth. Holding my breath, I stand in the doorway and take the quickest of peeks. Then I open my eyes wide.

It’s spotless.

I turn to him. He’s still fanning himself with the rolled-up magazine from the shock of seeing me. “What?” he says.

“You weren’t sick?”

“Yeah, I was. Of course I was. Why would I lie about that?”

“I don’t know. All I know is, this bathroom is sparkly clean, and you don’t strike me as the domestic type. Plus, you didn’t have any cleaning supplies, dirty paper towels—”

“Okay, Sherlock, you got me,” he sneers. “I just didn’t want to go on a crummy hike today. What about you? Why are you here?”

“I twisted my ankle,” I say, reaching down to massage it, though it really doesn’t hurt anymore.

“You didn’t want to go, either,” he says, collapsing on a leather couch. “Face it. You see it, too.”

I stare at him. Is it possible that Hugo, stupid, idiotic Hugo, could see some of the things I see? “See what?”

“Angela and Justin. Justin and Angela.” When my face is just as blank as before, he says, “In lurve.”

“What?” I start to laugh. Of course this wasn’t about the ghosts. But still, I know what he’s talking about. My laughter quickly dissolves. “What would make you think that?”

“You never noticed? They’re always giving each other looks.”

“Yeah, but they’re best friends. She’s not his type. Believe me,” I say, as much to convince myself as to convince him. “I mean, I can see where you would think that, because I’ve thought it, too. But really. It’s nothing.”

He shrugs.

“Really. They’ve known each other since they were three,” I say, thinking back to the time three years ago when we’d been making out in the yearbook office for the first time and Justin said, “Angela has nothing to do with this.” How many times have I repeated that to myself over the years? She’s his best friend, and that’s it.

Angela is my closest friend. She was happy when she found out Justin and I were a couple. Happy. She bounced around and giggled like she was on bath salts. “I always thought you’d make a great couple,” she said.

“Angela has nothing to do with this,” I find myself saying.

“Huh?” Hugo’s staring at me.

I grab my backpack and step over his legs, which are sprawled out on the coffee table. “I’ve got something to do.”

“Your poor, throbbing ankle all better?” he asks with a crafty grin. When I don’t reply, he gets down on his knees and raises his hands toward the heavens. “Praise God. It’s a miracle.”

I think about kicking him in the ribs, but in the end I just ignore him and walk to the door.

“Wait. Where are you go—” he begins, but by then I’ve slammed the door.

I walk on the right side of 201 until I’m directly across from the Outfitters, then cut across the highway quickly. That way, I avoid the sound of the river. If I hear those voices, I might get cold feet. And I need to do this. I need to put an end to the questions.

I know it’s completely ridiculous. I know I’m going crazy and seeing people who aren’t real. But they feel real, as real as Justin or Angela or anyone. And even though she can’t be over there, even though it’s impossible, I need to see. I need to prove to myself that all of this—Jack, Trey, my mother—is all in my head.

In the Outfitters, it’s quiet because the buses have already departed for the day. There’s a rather large older man there in red flannel and an L.L.Bean cap, reading a hunting magazine. I clear my throat. He looks up, startled. “Hi!” I say brightly. “I, um, saw an interesting graveyard on the other bank and I was wondering if there was a way I could get across to see it?”

He says yes with the first Down East Maine accent I’ve heard in a long time: “Ayuh.” Most people in southern Maine now are from away and don’t talk like that, which is a shame because I kind of like it. “You looking to rent a kayak?”

I bite my lip. “Well … if there’s any way to stay out of the water, I’d prefer that.”

All the while, his eyes are narrowed to tiny creases. Then he says, “Yeh the Ice Guhl!”

“Um, well …”

“Imagine that, the Ice Guhl wants to stay out of the riveh. What, the riveh got yeh good?” He’s all animated, suddenly. “Well, theh a footbridge ’bout sixteen miles upstream. At put-in. Yeh have to get down the logging roads. Gets hahd cause theh not mocked.”

I think for a second before I realize he’s saying “marked.” The roads are not marked. Great.

“Oh,” I sigh. Justin and Angela have taken Monster to get to the trailhead. Not that I would have taken it without asking him. He wouldn’t have minded, but with my luck, since it’s mud season, I probably would end up stuck on a remote logging road, never to be found again.

“That kayak soundin’ betta and betta each minute, eh?” he asks. “I’d take yeh, but I’m right out straight heh.”

I don’t know what that means, but it sounds painful.

“Yeh can still rent on a thuty,” he says.

I just stare. He writes something on a piece of paper and pushes it over the counter to me. It says $30.

“Cash only,” he says. “Dough know howah wahk those credit cah thingies.”

“Is it rough? Is it hard to get across from here?” I ask, my voice rising an octave.

“Nah. Buh yeh gah to make shaw yeh get theh befuh yeh reach the Kennebec. Gets a little hahd thah.”

I dig into my pockets for the money but stop. The feeling of dread—being on the water—washes over me. I can’t do it. As much as I want to see what’s over there, I can’t. “Isn’t there anyone else who could take me?” I ask.

He shakes his head, just as a voice calls out behind me, “I can.” I whirl around and Hugo is standing there, already holding a kayak paddle and grinning. He looks at the old man behind the counter and, in this most atrocious combination of Down East Maine and British Cockney, says, “It’s wicked calm, taint that right, govnah?”

I don’t care if he’s going to help me. I still have to smack him.

Chapter Fifteen

Hugo suddenly transforms into Mr. Athletic as he takes the kayak and fastens on his life vest.

“Do you really know how to kayak?” I ask, skeptical, as I pull a vest over my jacket and fasten the strap of the helmet under my chin.

He snorts. “Well, let’s just say I have more experience than you.”

I glare at him.

“I’ve been kayaking since I was nine,” he mutters. “Get in the boat. And don’t do anything stupid like falling out, okay? Keep your arms and legs inside the kayak at all times. And enjoy your ride.” The last part sounds like he’s a flight attendant.

I get in. The kayak is even mushier and more unbalanced than the raft. A few prickles at the back of my neck seem to be telling me to turn around, go to the cabin, and watch What Not to Wear. But it’s nothing too alarming. I can do this. I need to do this.

“What, exactly, about old cemeteries sounds good to you?” he asks as he sits in front of me.

“I don’t know. I like the history, I guess,” I say, which is the truth. When I was in third grade, we went on a class trip to Boston and I spent most of that time walking around the Granary Burying Ground. Most of the class went to the harbor, but my father asked the teacher to make an exception for me, because I was “afraid of the water.” And back then, I was, because my father had told me so many horror stories about it—that drownings happened all the time, that there were creatures with tentacles that could pull you under, et cetera. So I spent three hours hanging out with Sam Adams and John Hancock and a bunch of other dead people. It was interesting, but I was disappointed when the rest of my class showed up and not one of them had been maimed by an octopus.

Hugo nods and pats his camera bag. “I do, too. Wanted to go across. Thought I could take some pictures. Guess that means we have something in common, huh?”

I snort. The horror.

We push off and immediately follow the flow, but then Hugo begins to paddle. He does a good job of keeping up with the current at first, and even I’m impressed. I never figured that the spindle-limbed guy would have much athletic ability. Soon we’re halfway across, in the middle of the river. Hugo groans. His rhythmic motion falters a little, and he loses his grip and slows for a second. We begin to slide downstream.

“Keep going,” I call to him. “We don’t want to—”

He picks it up again. He mutters something like “I am” and some random curse word, which I’m sure is meant for me. I deserve it; I’m not helping at all, just calling out commands like a total backseat driver. I try to bite my tongue and let him do it, but then he stops again and we’re slipping farther downstream.

I can’t help it. I say, “Watch it, we’re—”

“I know!” he erupts. “Shut it, Miss Life-is-but-a-dream-and-death-is-the-awakening.”

I straighten. So, while looking for the Absolut, he found my book of private ramblings. What else did he find? “You went through my things? You disgusting creep!” I grab my paddle and nudge it into his spine.

“Ow, you bitch!” he snarls, and it must have been such a surprise because his own paddle slips from his grasp. He leans over and collects it before it can float away with the river. Though I have a great weapon, I guess this isn’t the time to use it on him for being such a complete and utter scumbag. Because now the current is pushing us back toward the east bank. I tighten my grip on the paddle, but when I look up, I hear something, partially drowned out by the helmet over my ears and the rushing water.

Whispering.

Oh no.

I look around. There is nothing on the west bank. I turn, scanning the dark water, and finally focus on the east bank. Trey is there. He is cupping his hands around his mouth and yelling something, but the whispers have grown to a deafening buzz.

By now we’ve slipped so far down the river that I can no longer see the Outfitters or the cemetery. I fumble to get my paddle into position, but my hands are wet with perspiration and it falls out of my grip, splashing into the water. “Crap!” I yell. A lost paddle is twenty bucks. I reach down to get it and wrap my hand around the cold metal pole. But when I try to pull it back up, it pulls me. And then I can feel it moving.

It’s not the paddle after all. It’s a hand.

And all at once I know what Trey is shouting. He’s shouting that I’m a complete idiot for not listening. He’s shouting that I should have left when I had the chance.

The hand wraps around my wrist, tightening. Hugo has his back to me now, and he’s fighting to keep the kayak upright, but it’s tilting toward the water. The pressure is too much. I know I’m going, because before the hand yanks me over, the water is once again whispering its welcome. And I know that what happened before wasn’t a freak accident. Things like this don’t happen twice by mistake. Maybe I belong here, among the waves.

I’m not sure how much time passes. It feels like just a blink of an eye. One moment, I’m bracing for the shock of the cold water, and the next, I’m lying on the ground, coughing and sputtering river water all over myself. I sit up and immediately bonk my head into something hard. When I say “Ouch!” someone choruses with me.

“Damn, girl, is this the thanks I get for saving your butt twice?”

I open my eyes. Trey is there, rubbing his forehead. I try to apologize but end up coughing up some gritty black water into my hand. Gross. I wipe it on my life vest and look around. We’re back on the east bank, a little downstream from where I set off. I know this because I can see the dock and the green roof of the Outfitters in the distance. The kayak is nowhere in sight. I’ll probably have to pay for it and the paddles we lost. After all, it’s not Hugo’s fault.

I sit bolt upright. “Oh no. Hugo!”

“Relax, kid. I took care of him. He’s back at the cabin, sleeping. He probably won’t remember much of this when he wakes up.”

“How can you … I don’t understand.…”

“Yeah, you don’t. That much is clear. So now’s my time to do some explaining, I guess.” His tone is angry. He wrings out the lower hem of his old shirt, which is open to the waist, revealing his tan chest. He catches me looking and I blush.

He turns away and starts pacing the shoreline. There are thousands of jagged little rocks and pieces of debris on the edge of the river, but they don’t seem to bother his bare feet. Well, of course not; he’s not real. “I thought I told you to get. What the hell did you do that again for?”

“I want to see my mother.”

Surprise dawns on his face. I expect him to tell me that I’m crazy, that she’s dead and gone and that’s the end of it. Instead, he narrows his eyes. “You can’t see your momma. It’s impossible.”

“But she’s there? She’s across the river?”

He looks away, then nods reluctantly.

“So what Jack said was true,” I whisper.

“No. Look.” He comes up really close to me and grabs my wrist. “What that piece of slime says to you is always wrong. Don’t you ever listen to nothing he’s got to say. Got it?”

I don’t like the way he’s pulling on my wrist, almost hard enough to dislocate it. He looks down at it and remorse dawns on his face as he slowly releases it, then rubs the red welt his fingers have left.

“I’m sorry, kid.”

His fingers are rough and misshapen. There are sore-looking red circles there, popped blisters, and scabs all over his palms. I pull my hand away from him. “Are you a ghost, too?”

“I’m a guide,” he says.

“A guide for what?”

“I took your momma across. You were a kid then, so you don’t remember.”

“Of course I remember. You don’t think I remember my own mom dying?”

“Sorry, kid. Anyway, that was my job, taking her across. And it’s my job to take you across, too. When you’re ready. And you ain’t ready.”

I stare at him hard. “You … you …” And suddenly I remember it all. My little fishing spot on the river. I went out there every day during the summers. My mom bought me that expensive new pole for my seventh birthday, and she would pack lemonade for me in a blue cooler and tell me to bring home a shark. And then one day that boy showed up, that funny-talking kid. He said he was waiting on a girl. My mother died three weeks later, and I never went back to that fishing spot again. “That—that was you?”

“You remember me?”

“I remember you catching all the fish in the river and letting them go. I was so angry.” And then a realization hits me. “You … guided my mother? To where?”

“Across the river. To the place of the dead.” He thunks on his temple as if to say Where’s my head? “She—you—you are both river guardians. Royalty among the river dwellers. You probably didn’t know that. She didn’t know much about it, either, when I guided her.”

“Wh-what?” I can’t say anything more.

“The water is no place for final resting. It’s always moving, too volatile. People who meet their deaths on or near the river need someone to guide them somewhere quiet, safe. Across the river. That’s where you and your mother come in.”

“And you? You are a guardian, too?”

He shakes his head. “My only job is to fetch the guardians and do what I can to protect them. I don’t have your power. You have great magical powers, Kiandra.”

I raise my eyebrows. “Like what?”

He chuckles. “Kiandra, you have no idea what you can do.”

I just sit there, numb. The idea is crazy. It’s crazy enough to be seeing these ghosts, but that my mother and I could have powers, could be tied to the water in that way? Nuts. “I think you have the wrong person. I do not have powers. I can’t even put on a wet suit. And I nearly drowned in the river. Twice,” I say, but all the while I’m thinking about my visions. About how my mother always loved the water so much, and how her skin was always clammy and smelled damp. How when she finally disappeared into the river forever, despite the horror of that event, a small part of me said, Well, of course she did.

He comes in close and sits on the bank next to me. He smells like pine needles and something spicy-sweet. “Do you need me to prove it to you?”

I nod. “That would be nice, since it’s kind of impossible to believe.”

“You didn’t have to rent a kayak to go across the river, kid,” he says.

“What? Are you saying I can part the waters? Or walk on water?” I joke.

He smiles. “Which would you prefer?”

My jaw drops. “I was only kidding.”

But his face never changes. I get the suspicion that he’s serious. “But you don’t want to go over there,” he says. “If you’re over there, you ain’t alive. And I’m trying to keep you alive. So don’t try to go over there again, okay?”

“If I have such control over water, then why did you have to save me from drowning twice?”

“Because you don’t know how to use your abilities, kid. Until you do, you can’t protect yourself from nothing,” he says, shaking his head. “You are Mistress of the Waters. That’s no small thing.”

“Mistress of the Waters?” I say the words, tasting them.

“Yeah.” Then he mutters, “Pretty much the sorriest Mistress of the Waters I’ve ever come across.”

I cross my arms. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I’ve brought dozens of your ancestors across. But you are … different. I’m not supposed to take you across. Not yet. But damned if you’re not giving me the hardest time keeping you out of trouble. You don’t listen. You didn’t listen when I told you that fancy pole of yours wouldn’t catch you nothing, and you don’t listen now.”

I snort. Am I really being lectured by a ghost about how to live my life? “Jack told me he was sent to take me across.”

“No,” he says, his face stone. “Jack is no good. He’s lying to you, trying to trick you.”

“I don’t understand. What does he want from me?”

He’s not looking at me anymore. He’s scanning the riverbank. I don’t think he heard my question. He reaches down and grabs my wrist. “Look. We’re not safe here. Can we go somewhere?”

“You can come back to the cabin with me.”

He hesitates. “Can you see the river from there?”

I nod.

“I think I can do that. Can’t get too far from the river.”

“Or what?”

“Or I get pulled back. The river’s like a stake in the ground with a chain tied to it. And I’m the dog.” He reaches down and helps me stand. “Can you walk good? How’s that ankle of yours?”

“It’s not too bad,” I say, putting my weight on it. I hop up and down. It’s just a numb ache, barely perceptible. I move it back and forth, testing it, but then suddenly I must do the wrong thing, because pain shoots up my leg. I shriek and fall to my knees. “Except when I do that.”

He reaches down and touches it. I feel the rough skin on his finger pad just barely swiping under my anklebone, and the whole thing begins to tingle. “Better?”

I jump. I move. I do everything I did before, but the pain does not come back. “So you did do it, last time? To my back? You can heal me?”

He nods like it’s no big deal, and we start to walk toward the cabin. He’s looking over his shoulder. Something is bothering him. As I walk behind him, I notice he is leaving a trail of small droplets of black blood on the dirt. I rush to keep up with him, and though he’s holding his arm close to his chest, I know it’s that same cut that’s bleeding. It looks as fresh as ever. I pull off my jacket and clamp it over the thing. He doesn’t argue. “Old war wound or not, I’m not letting you bleed all over the cabin.”

“Thank you,” he says softly.

“You’re Trey Vance, aren’t you?” I ask him, finally. “The boy who told on those other boys who killed the girl. I heard your story. They pulled a knife on you. That’s where you got that cut. And you jumped in the water but you couldn’t swim.”

He laughs, but there’s sadness in his voice. “That’s what happens over time. Stories get twisted out of shape. But no. I couldn’t swim. Lived my whole life by water, first in New York and then in Oklahoma, and never learned to swim. How’s that for irony? The one at my home outside of Tulsa was muddy and full of them leeches. No fun. Some kids on the river where I died even made a rhyme up about it after, as a warning.

“Trey Vance, who took a chance

And was pushed in the river grim

.

He lost his life not by a knife

But because he couldn’t swim

.

“They say I’m famous in twelve counties. Whenever kids don’t want to learn to swim, their mommas always say, ‘Now, little Bobby, you know what happened to Trey Vance, don’t you? Get your butt back in the water.’ ”

“Thought you said you were a ‘powerful good swimmer’?”

He nods. “That’s the good thing about this place. You get to be what you wanted most to be when you died. And hell, if I’d have been a good swimmer, I’d still be alive.”

I look down at his arm, which he’s hugging to his body. “You can heal me, but you can’t heal yourself?”

He shrugs. “That power’s beyond me.”

“Is it beyond the all-powerful Mistress of the Waters?”

“You joke about it, but that’s ’cause you don’t understand it,” he says. We cross the highway and start up the driveway. “Can’t heal the dead. But you can bring a person back to life. The Mistress of the Waters can do that. It’ll damn near destroy all her power, but she can do it. I think that’s what they want your momma for.”

“Who wants her?” I sputter.

“They want her to make them alive again.”

“Who?”

“Don’t know. Jack, I think.” His face twists. “It’s hard to get you to understand, when even I don’t know what’s what, sometimes.”

I groan. “I want to understand it, but you’re making it so damn hard. If I’m destined to become this royal-over-the-waters, shouldn’t I just go and accept my destiny?”

“No. Not now.” He stops suddenly, trying to think of the words, then exhales, defeated. “Being here is dangerous. Too dangerous for you.”

“Why? Is it because of Jack? Who sent you, anyway?”

“Mistress Nia,” he says softly. “Your momma.”

Every time someone says my mother’s name, I cringe inside. I’m so used to having that reaction to her, I can’t rid myself of it. And so when Trey says her name again, I bite down hard on my tongue and don’t say a word until we’re in the cabin. When I open the door, I can already hear loud snores emanating from one of the upstairs bedrooms. Hugo, no doubt. Our little kayak trip seems a million years away, almost as if it never happened. And the funny thing is, when I look down, I realize my clothes are completely dry. Not like they dried, but like they were never wet in the first place. They’re not stiff with river grime. My hair even smells like the shampoo I used the evening before.

I turn to Trey, about to ask him why my mother would send him as a warning, when I see him staring into the hallway mirror. There’s no reflection. I am standing behind him and yet all I see in the glass is myself. He shakes his head. “I ain’t seen myself in a mess of years. What year is it now? 1940? 1945?”

I know my eyes are bulging. “What year did you …”

He chews on his lower lip. “Last I was like you, it was 1935.”

How could he have somehow misplaced so many years? “It’s much later,” I say.

He grimaces. “It’s hard keeping track of the days here. I tried for a while but lost it.” He runs his hands through his hair. “What do I look like now? Hell?”

“Um … fine,” I say. For someone who has been dead for so many decades, he doesn’t look half bad.

He looks around the house and whistles long and loud. “This the way people living these days? This a hotel?”

“No, it’s Angela’s parents’ vacation cabin.”

He raises his eyebrows. “Just the three of them? Live here?”

I nod. “But only a couple weeks out of the year.”

“Dang, I was born at the wrong time.” He walks into the kitchen and opens the freezer. “Heh. If this ain’t one of them—what are they called? Refrigerators. We had one. Brand-new. My dad got it for my momma for her birthday.”

He turns the under-the-counter can opener on and steps backward in a hurry when it begins to whir. I help him shut it off. “That opens cans.”

“Angry little thing, ain’t it?” He shakes his head at it like it’s a naughty puppy and begins playing with some of the other appliances. I explain each one to him, and each time, he laughs and shakes his head. Then he turns to the microwave. “What’s this? This chew the food for you?”

He doesn’t wait for an answer. His eyes fasten on the fake moose antlers over the fireplace. He whistles again. “Must’ve took ten men to bring that beast down, heh?”

I don’t want to tell him they’re fake. Based on the way he reacted to everything in the kitchen, he already knows the people of today are a bunch of wusses who can’t do anything for themselves. “Um, I guess.”

There’s a noise in the foyer, probably just the house settling, but it reminds me that Angela and Justin might come home at any minute, or Hugo might wake up. Trey has moved on to the bookcase. “Hey, I had that one, too. Journey to the Centre of the Earth. My momma bought it for me on my seventeenth birthday. Never finished it, though. Died before I could.”

He says it so matter-of-factly, it makes me gasp. “You can borrow it, if you want,” I say, since I doubt that any of us will be doing any real reading this weekend.

“Yeah?” He gets all excited, like I offered him a Porsche, and takes the book down from the shelf. He stares at it for a minute, and then gently puts it back. “I’d best not. Don’t want to muss it up.”

“Um, I’m afraid you can’t stay here. My friends will be back any minute,” I say.

“They can’t see me, kid.”

“Yeah, but I can. I can’t act normal if you’re around.”

He nods. “All right, all right. But knowing your momma wanted me to protect you, ain’t that enough for you to get yourself home?”

I shake my head. “I don’t know who to believe. Jack is telling me one thing. You’re telling me something else. All of it is so unbelievable. And I know I should be running in the other direction, but I can’t leave until I know. If my mother is here, I want to see her.”

He throws his hands up in frustration. I’m clearly getting on his nerves. “I told you. That ain’t possible. Across the river is her kingdom. She can’t abandon it. You can’t see her unless you cross the river. And you need to be dead for that. If you cross, you ain’t coming back. And you like your life, don’t you? You don’t want to leave it?”

“I do, but—”

“There’s another part to this story. Listen,” he says, his face turning to stone. “According to your momma, there’s a relation of yours from many years ago. This person would have inherited the title, but died very young, and has been living on the outskirts of your momma’s kingdom, in the shadows. The story is that ever since this person came here, they’ve been wanting to step in. They’ve been off in secret, developing these powers. This person’s been in this kingdom a long time, longer than your momma’s been ruling, and they’re awful strong. Stronger than your momma. Stronger than you, because not only was this person destined to rule, but they know more about your powers than anyone. And they’re angry. Real angry at your momma.”

I swallow. “I don’t understand. Who is this person? Jack?”

“Doesn’t matter. All it means is that you need to get.”

“Can’t my mother just come to the edge? Just so I can …” I trail off. This is so stupid. Asking to see my mother. My mother, who abandoned me. She’s dead. Gone. Even if I could see her, I shouldn’t want to.

“It doesn’t work like that, kid.”

I exhale. “Of course it doesn’t. Can you tell me something? When you die, do you stay here forever?”

“No. Everything fades. From the moment you were brought into the world, you were dying. How fast you do that is up to a lot of things. I’ve been here more years than I can count. But I guess it’s good to know that when things end, you can start again.”

I blink, fighting back the memory of my mother, sitting on the edge of my bed, telling me something so similar. Sometimes things end. And it’s comforting to be able to begin again.

He wags a finger at me. “But listen, girl. Stop getting ideas. If anything happens to you, your momma’ll skin me. Not alive, because that ain’t possible, but you get the picture. You’re all she ever talks about.”

“I—I am?” I sputter. I can’t believe that’s true. He must have me confused with someone else’s daughter. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. “I can’t leave. Not when I know my mother is over there.” I bite my lip, thinking of my mother. She left me; why wouldn’t I do the same to her? But the answer is immediate: I’m not like her. “I don’t abandon my family.”

Now he starts to pace around me, hands on hips. When he stops, his eyes burn into me. He’s angry. “If anyone could be the death of me, you’re it. You can’t do nothing about it, kid. Accept it. Just do what your momma said.”

I start to argue with him, but then I hear something. We both freeze at the sound of tires on gravel, coming nearer, up the driveway.

He reaches out and at first I think he’s going to poke me, but instead, he gently touches my cheek with his icy finger, leaving a line of tingles there. I wonder if it tingles that way because he’s not human or for another reason, but already I yearn to feel it again. I want to grab his hand and keep it there, but before I can, he says, “Go home.”

And then it’s like he was never there at all.