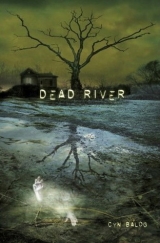

Текст книги "Dead River"

Автор книги: Cyn Balog

Соавторы: Cyn Balog

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

The wind picks up, finding its way to my neckline. I pull the blanket around me and suddenly it’s clear to me. They’ll get him when he goes fishing.

I don’t know how, but suddenly the thought is so clear to me. So obvious, like it’s happening right in front of me, right now. I see him tying string to a pole, and beyond him, in a lush forest, a tree branch bends. Someone is watching him. But he is turned away. A lock of dirty-blond hair falls in his eyes and he sweeps it behind his ear, unaware.

Somehow, for some reason, I know more than even he does.

“For a few days,” Justin goes on, “Trey wrestled with what he’d seen, wondering if he should go to the police. But one of the boys, it turns out, saw Trey as he was running away. So one day Trey was walking to the river, completely unsuspecting.”

When Justin mentions the river, suddenly I see the kid at the edge of the pier, in his dirty jeans, with his stick fishing pole. That’s the one. Get him. I open my mouth, wanting to scream to him, to tell him to watch out. He doesn’t know they’re behind him. He won’t know until it’s too late. But I can’t find my voice.

Suddenly I can’t breathe. My lungs are going to explode. Almost as if I’m underwater.

Like he was.

He turns. There’s a knife. Someone slashes at him. A red gash opens on his forearm and he drops the pole. Slash again, and he dives out of the way. Into the water. The water is greenish-black from the shade trees above. He surfaces, but the water is too deep, much too deep for him to reach the bottom. He struggles to stay afloat, to find something to grab onto, but in his panic everything falls through his grasp, until the only thing left is the sound of splashing mingling with laughter.

“He can’t go fishing!” I shout, finally getting the air into my lungs. I gasp, again and again and again.

Justin turns to me, his eyes orange with firelight. “You’ve heard this one before?”

I can’t stop shaking. “Please, Justin. Can we just go to bed? I’m tired. Please.”

He studies me. “All right. It’s late anyway. We have to get up early.”

It’s only then I realize Angela and Hugo are both staring at me. Ange says, “You look tired, Ki.” But I know from her expression she means I look a lot worse than tired. I hug myself tight, creeping closer to the fire, but even that doesn’t stop the shivers. Ange whispers to Justin, “You’ll have to tell me the rest later.”

But I know the rest. Somehow, I was there. I saw it all.

And I saw him die.

Chapter Four

I curl up on the shag throw rug in the dark bathroom, which is lit only by moonlight streaming through the window. I press my fists to my eyes until I see fireworks. Down here, I don’t hear the rush of the water. Down here, I almost feel safe.

My dad is a teacher at my high school. He teaches my European History class and about fifteen extracurricular activities, from Driver’s Ed to Debate Club. The parents of freshmen learning how to drive don’t have to worry about a thing, really; besides Justin, my dad is probably the safest person in the state of Maine. I mean, I had to beg and plead with him, nonstop, for three months, just to get him to agree to a weekend camping trip two hours from home. And when he finally agreed, he handed me a copy of Camping for Dummies and quizzed me on each chapter, every Saturday. In fact, should we run out of the twelve days’ worth of food he packed for me before I left, I know how to set a pencil snare so I can catch a rabbit.

Justin is on the swim team at school. When my dad noticed that we were hanging out a lot more in the hallways, he got that worried look in his eye, but he never said anything. And one day I went to Justin’s swim practice to cheer him on from the bleachers, and Justin came up to me between laps to say hi. He was usually very suave, because this was the beginning of our relationship and he was trying to present that really good side of himself that everyone puts forward when relationships are new. But right then, he was nervous. “How are you?” he asked, fidgeting.

“Fine. Are you worried about the meet coming up?” I asked him.

He shook his head, water spraying on my lap.

“Nervous about … um, me being here?” I ventured. Maybe my presence intimidated him and would affect his performance.

“No, that’s not it. I’m fine,” he said. I could tell he was distracted. He kept looking past me, toward the back of the bleachers.

So I stayed for a little while longer, wondering if he was just not interested anymore. Which made my stomach drop, because for weeks I’d thought about him more than I breathed. Then, as he hurried back to the pool, I got up and started to leave. And who did I see at the top of the bleachers, his nose buried in The Establishment of European Hegemony 1415–1715?

“Dad,” I said to him later, “I’m fifteen. I don’t need you following me everywhere I go. And Justin is a good guy.”

He’d had a strange, sad smile on his face. “I know, I know,” he said.

My stomach did cartwheels. Nobody could doubt that Justin was the most upstanding of guys. Good grades, always deflected trouble, made friends easily with everyone. If my dad had a problem with him, then I was positive there was nobody in school he’d approve of. Maybe nobody in the world. “Well, what don’t you like about him?” I asked.

He didn’t answer, and I was glad, because I thought I knew. It was such an embarrassing thing, I really didn’t want to hear him say it. He couldn’t cope with me growing up, I was his little girl, his everything, and no guy would ever be good enough for his “everything.” I guess I couldn’t blame him, but at the same time I imagined myself sitting home, alone, at the age of sixty-two, still not allowed to date.

From then on, I’d often catch him in the hallways outside the pool when I went to watch Justin at swim practice. I’d just see a shadow, a hint of his army-green herringbone blazer, a flash of his scruffy beard in the doorway. It was almost as if I’d drawn a line in the doorway and he’d made the decision not to pass it. But he couldn’t stop himself from checking up on me from afar.

I didn’t mention it to him. I thought I understood. I didn’t realize how wrong I was.

One day, I went to watch Justin practice golf. Justin isn’t a great golfer, but he wants to be one, so he joined the team. That first day, I looked around and around the field and my dad was nowhere to be seen. What about watching Justin golf is so safe? I thought. Or what about watching Justin swim is so dangerous? He thinks I’d be so enamored of Justin in a Speedo I’d jump him?

But suddenly it came to me. My dad wasn’t having trouble coping with me growing up. He didn’t have a problem with Justin at all. What he had a problem with was the thought of me drowning, like she did. Even the thought of a swimming pool. Suddenly it hit me, why I hadn’t been to the beach in ages, why there was no water anywhere near our house, why, when I was invited to pool parties, he always made sure we were busy. It was crazy, but it was true. He was that freaked out by my mom’s death that he couldn’t stand it. But me, on the other hand … I was fine with it. In fact, it didn’t bother me at all.

I decided to confront him. I knew exactly how. “Dad, I’m thinking of taking swimming classes,” I told him casually after our usual mac-and-cheese dinner.

His eyes filled with dread. For a moment he looked like he might choke on his mouthful, but he brought his napkin to his mouth, wiped his graying beard, and cleared his throat thoughtfully. “You’re not a strong swimmer, Ki.”

That was true. I hadn’t been swimming since before mom died. “Well, duh, that’s why I want to take classes,” I said. “Justin said he’d help me practice.”

“You have yearbook and band. Doesn’t it interfere—”

“Nope. It’s good. I checked already.”

He shook his head. “I think you need to keep up with your studies. It’s just too much.”

“Dad,” I said, the anger boiling in me. “It’s. A. Pool. It’s not some raging river. And what happened to her will never happen to me! Stop constantly trying to protect me from her!”

He’d stared at me for a while, silently, gripping his paper napkin until it ripped down the center. And then he got up from the table, from his half-eaten dinner, and walked into his bedroom without another word. We didn’t talk for days after that, and when we finally did, it was like the previous conversation had never happened. But I was still angry. Really, how could he be so ridiculous? To what lengths would he go? Maybe next he would forbid me from taking baths. Walking in rain showers. Getting Big Gulps at the 7-E.

But now I can’t help but wonder if there was something more to his concern. I’d never told him about the visions I’d had. It seems crazy to think that just because my mom drowned in a river, he’d want to keep me completely isolated from water. And yet he’s been almost fanatical about it. He’d yanked me away from the river back home so quickly, we didn’t even have time to pack. And now, why am I having visions, visions I haven’t had in ten years, now that I’m by the water again? Maybe there is something else he’s afraid of.

No. What else could there be? He was just being protective. I’m his little girl, after all.

I stand up and twist the handles on the faucet, hoping to splash some water on my face, but nothing happens. Then I remember that the water has been turned off. Perfect.

It’s just my overactive imagination, I tell myself. Those things I saw … they’re not real. They can’t hurt me.

Someone raps on the door. “Ki? You okay?” Justin.

“Fine,” I say, wiping my face with some wadded-up toilet paper, not that it’s doing much good. “I’m just—” I stop, wondering what I can lie about, considering there’s no water in here. “I’m good.”

I click open the door slowly and find his concerned eyes in the darkness. “You sure?”

“Oh. Yeah.”

“Have to be up early tomorrow. The sunrise from the top of Grey Mountain is amazing. Want to go for a hike when we wake up?”

Sure. Trekking through the predawn blackness in freezing temperatures. Sounds lovely. I don’t say anything, but my body stiffens.

“It’s okay. Maybe I’ll go myself, then,” he says, putting his arm around me. “Nice and warm in here. Why don’t you sleep in a bed tonight?”

“I told you, I’m fine,” I say, but it comes out more like a snarl. I’m going to be perfectly okay here, and nobody—not him, not my dad—is going to tell me any different. I muster a smile. “Lead the way. Out to the campsite. Bring it on.”

He must be fooled by my resolve, because he throws up his hands. “All right. Yes, sir!” he replies, saluting.

We go back to our sleeping bags. Hugo is already snoring, making this embarrassingly loud noise that will scare anything away, so we don’t need to worry about wild animals raiding our camp in the middle of the night. Not that I’m expecting to sleep much. Angela is sitting propped up on her elbows, looking at me across the fire. “You okay, Honey Bunches of Oats?” she asks me.

For as long as I can remember, Angela and I have been calling each other by the names of popular breakfast cereals. “Sure thing, Cocoa Puffs,” I answer, pulling back the cover of my bag and inspecting it for creepy-crawlies.

“I can get you a cold compress or something.” Her eyes are big and round again, worried. It’s amazing how like her mother she is. The minute I arrived in Maine, Aunt Missy was at my side, playing Florence Nightingale. She was the Cold Compress Queen, always bringing something to put on my forehead and massaging my temples until I’d relax.

“I’m good,” I say, smiling at her, though my head is throbbing and I’d love someone to massage my temples. It makes me think of my mother’s headaches.

No. I’m not like her.

When I slide into the bag, I still don’t feel warm. I move closer to Justin but I don’t think it will do any good, even when he drapes his big arm around me and pulls me to his chest. I close my eyes, concentrating on the crackle of the fire, and slip my clammy hand into Justin’s warm one. But the only thing I can hear now is the river. It whirrs along, until soon my hand in Justin’s doesn’t feel just clammy … it feels wet. My feet, too.

I move my legs, but it’s like wading against a tide. They ache. My feet are submerged in water—icy, numbing water. I can hear them sloshing through it as I move them in the bag.

What the—

I jump upright and kick off the sleeping bag. My wool socks are completely dry. Justin has his eyes closed and is lazily feeling around for me, to pull me back. “Um, I thought I felt a spider,” I whisper, but he doesn’t seem interested in the explanation, just mumbles a good night. I go back to the place Justin’s body has carved out for me, and hope hope hope that I’ll be able to get even an hour’s worth of sleep tonight.

Justin’s breathing becomes deep and soft, lulling me. His breath on my ear drowns out the whispers of the river. Sleep comes.

Chapter Five

I’m woken as a trickle of water slides down my cheek. Wet, again. I try to push the thought away. It’s just my imagination, my stupid imagination, I think, when another droplet lands on my forehead.

Water?

I turn onto my side, stretching, reaching for the clock at my bedside, but my fingers wrap around something wet, cold, and stringy. Weird. I roll back over, wipe my eyes with the heels of my hands, and try to open them. Instead of that helping me to see, my retinas start to burn. I keep blinking. Again and again, until I focus on my palms. They’re smeared with black mud, bits of gravel, and slivers of grass.

Springing upright, I remember. I’m outside, camping. I’m in another world, so different from my bedroom. There’s a thick mist hugging the trees, only a peek of their dark trunks exposed. A thin drizzle is falling. I blink, finally focusing on Hugo, who is yawning and stoking the dying fire. He looks haggard, every bit like he just spent the last six hours sleeping on the cold, hard ground.

Then I remember the night before. The storytelling around the fire. And I realize something.

I slept. I slept well, in fact. Really well. So well that I forgot where I was. Considering all the weird things that happened yesterday, and what lies ahead, that’s nothing short of amazing.

I look around for Justin, but it’s just Hugo and me. No Angela, either. The wind has picked up; it’s whistling through the trees, carrying the sound of the rushing river. “Where is everyone?”

“Went for a morning hike. To see the sunrise. Or something twisted like that.” He clears his throat. “I need coffee. You want?”

“Yeah,” I say, rubbing the sleep from my eyes. “Why didn’t you go?”

He fixes the pot over the fire and leans back. “Saving my energy for the river. Besides, I didn’t want you to wake up to a bear crapping on your head.”

I can’t believe I missed all the commotion of them getting up and leaving. I was sleeping that soundly. What a difference a good night’s sleep can make. Rafting doesn’t seem quite so scary now. But hiking up a mountain at the crack of dawn to see the sun? Crazy. I guess Angela and Justin are two peas in a pod that way. A feeling of dread passes over me as I realize something. They went to see the sunrise. “But it’s raining.”

“Just started. It was dark an hour ago,” he answers. “When they left. To see the sun come up, it helps to leave before it actually comes up.”

What a snot. I guess there are some things a good night’s sleep will never remedy.

“But …” I stand there, trying to think of something to say about the two of them running off together on a rainy day to see the sunrise that won’t make me look like a jealous girlfriend, but everything seems wrong. Really, I’m not worried. It isn’t possible for him to do anything underhanded. Even thinking about it would give him hives. And Angela—not only is she my cousin, she’s like Mother Teresa. They’re so … alike.

Hugo picks up his camera and grins. “I got some good pictures. You know you were drooling?”

My mouth drops open, and all of a sudden I can feel a spot of drool hanging over my bottom lip. I swipe at it. “If I find out you took pictures of me while I was sleeping, that thing is going to be in the river faster than you can—”

“Hey, hey, hey. Chill,” he says, as if he wasn’t the one who started it. “I only photograph subjects that interest me.”

I glare at him. That’s it. Angela is no longer my cousin. It’s bad enough I have to deal with his attitude every day after school in the yearbook office, but this is torture. There are still a few weeks left before yearbooks get printed. I’ve been toying with the idea all year long since I was appointed editor of the seniors section, but now I’ve pretty much decided that the entry under his graduation picture is going to have an unfortunate typo: “Huge A. Holbrook.” A smile comes to my lips as I imagine it. “When do we have to leave?”

“Right about now,” Justin’s voice echoes somewhere in the woods. A second later, he’s climbing down the rocky slope toward us, wearing a yellow hooded rain jacket, hiking boots, and shorts despite the frigid weather.

Angela follows behind him, hands in her pockets. “Well, that was a big bust.” She sighs, annoyed. “Maybe tomorrow.”

“Come on. We’ve got to be there by eight.” Justin starts stuffing his backpack with supplies. Suddenly he looks at me and leans forward, kissing my forehead. “Morning. Sleep well?”

“Yep. Great,” I say.

“You ready to do some rafting?” I’m about to nod and say “Ready as I’ll ever be” when he narrows his eyes at me. “Going for the tribal warrior look?”

“Why?” I begin, and then I realize he’s staring at my cheeks. Out of the corner of my vision, I can see something black on my nose. Dirt. I start to swipe at it with my hand and Justin takes his sleeve and wipes it, too. Feeling stupid, I ask, “Better?”

He nods. “I kind of liked it the other way, though. Made you look tough.”

He would. That’s Justin for you. He’d much rather a girl sport war paint than lip gloss.

Northeast Outfitters is right across Route 201, so once we pack up all our stuff, we head across the road and into a log cabin. There are already groups of people hanging around outside on the deck, wearing wet suits and slurping down coffees in Styrofoam cups. Most of them are older people, in their thirties and forties, maybe. They look really adventurous. Well, more adventurous than I do, I’m sure. Hell, I’m nervous about how stupid I’m going to look in my rented wet suit.

Here we’re close enough to the river that I can look across to the other bank. Scattered among the black pines are bits of gray stone and concrete, what looks like the broken remains of some old building. For a moment I think I see someone moving there, but when I focus I realize it must only be the pine trees sweeping back and forth in the wind. At least, I hope.

When we go inside, Justin saunters up to the desk, self-assured. “Hey, Spiffy!” he calls, and I know he’s talking to Pat Skiffington, one of the guys who work here and one of Justin’s oldest friends. Justin’s family has been coming to the Outfitters for so long that the two families exchange Christmas cards—the last one I saw from the Skiffingtons had Frosty careening down a river in a yellow raft. Even when planning for this trip was in the earliest stages, it was always “Spiffy will hook us up” and “Spiffy knows this river better than anyone.” I peer around the shoulders of the other people in the room to see a guy with the most shocking red hair and freckles clap Justin on the back and say, “Yo, man!” He’s wearing a Red Sox cap turned backward and a rumpled T-shirt, and he looks about as unspiffy as a person can get.

I hang back with Angela, who is trying to find one of her booties in her bag. She and Justin brought their own wet suits, since they’re up here all the time, and Hugo borrowed his brother’s. But for me, it’s rental city. Ugh. I don’t really like the idea of a suit that hugged someone else’s most private body parts hugging mine, but I’m determined not to complain. I’m determined to be okay with roughing it, which was why I pretended it was just fine that we didn’t brush our teeth, despite the thick film on mine that I keep trying to wipe away with my tongue. I bite my lip and focus on the pictures in a glass case along with a huge map of the state. Photographs of dozens of smiling people in ballpark-mustard-color rafts, surrounded by white water. They all look so happy. I don’t know if it’s possible for me to smile like that. Well, not surrounded by a raging river, at least.

Then I turn to another picture that looks out of place among all the color photos. It’s faded and yellowing, part of an old newspaper article, and the frame itself is cracked and covered with what looks like years of dust. The headline on it says: RIDE THE DEAD RIVER WITH THE SKIFFINGTON BROTHERS. There are two men, one clean-shaven in a suit and tie, and the other in a beard and a flannel shirt, standing under a GRAND OPENING sign on the porch of what must be the same cabin I’m standing in. The date on it is July 18, 1992.

“Got it!” Angela says, triumphant, hopping around to squeeze the bootie onto her foot. She’s already wearing her wet suit. It’s cute, mostly black with a little pink stitching. She looks even better in the wet suit than she does in regular clothes: strong, statuesque, and athletic. I think I will probably look like a full garbage bag in mine: lumpy, shapeless, and sadly waiting to go to where its life will end.

Justin motions to us. I move through the crowd and lean against the desk as he hands me a pen. “You guys just need to sign this release,” he says.

I read it as both Hugo and Angela hurriedly scribble their names on the line. I have to focus on my breathing when I go down the list of possible risks: “disease, strains, fractures, partial and/or total paralysis, death, or other ailments that cause serious disability.”

I repeat Angela’s words to calm myself. Smooth sailing.

Then I stop when I see: “Signature of parent or guardian if under 18.” I look at Justin. He mouths, It’s okay. Just do it.

I hesitate for only a second. This is Justin. Justin, who always checks my seat belt to make sure it’s fastened before he takes Monster out. Justin, who religiously stays to my left when we’re walking down the sidewalk, to protect me from whatever peril might lie in the street. He wouldn’t have me sign anything unless there really was no danger involved. It’ll just be a leisurely jaunt down the river. Smooth sailing. I grab the pen and sign Kiandra Levesque.

“Let’s get you a suit. It’s twenty to rent,” Spiffy says, inspecting me as I fork over the crumpled bill that’s been glued with sweat to my palm. I think he’s probably just trying to figure out what size I am, but when he turns around and walks into the back of the office, Justin winks at me.

“He does not want me,” I mutter.

“Totally does.”

“You’re crazy.”

“I’m right.”

I stick my tongue out at him just as Spiffy appears in the doorway with an amorphous gray thing with pee-yellow arms that looks like it has seen better days. “You can try it on here,” he tells me, motioning to the back. “Want some help?”

I look at Justin helplessly. Is that some backwoods pickup line?

He grins at me. “Let him help you get dressed,” he whispers. “It will be the highlight of his young life.”

I scowl at him as Spiffy just pulls aside the curtain and lets me pass, as if he’s dressed teenage girls in neoprene a million times before. “You wearing long underwear?”

The curtain swings back, effectively shielding me from Justin’s I told you so expression. I nod, stripping off my North Face jacket. I’m actually wearing two layers of water-resistant skin and two pairs of extra-thick wool socks that go up to my knees because I know I’ll be freezing. Justin is wearing long underwear, and if he, the Snowman himself, the man who is known to traipse around in the dead of winter in nothing but gym shorts, is wearing long underwear on this trip, I know we’re talking about some serious cold. I stare at the suit as Spiffy holds it out to me. “How do I get it on?” I laugh nervously. “I’ve never—”

“Here,” he says, leaning over and helping me step into it. I nearly fall over a few times before zipping it up over my long underwear. As I’m leaning over to fasten the booties, feeling as flexible as a sausage in its casing, I realize the suit smells like feet. Feet with a thin Febreze mask.

I swallow as I look at myself in a floor-to-ceiling mirror. I’m pretty thin, but that doesn’t matter: I look like a sausage, or rather like a plastic bag of potatoes, lumpy and round. “Um, so,” I say, trying to take the focus off my foxy wet-suit-clad body, “your dad started the Outfitters?”

He nods. “My dad and his twin brother.”

“Twin? I was looking at the picture in the lobby. They don’t look very alike.”

“They aren’t. They lead completely different lives. My uncle is really into rafting and convinced my dad to invest in the Outfitters. My dad isn’t into that stuff at all, but he has a lot of capital.” He smiles. “My dad kind of hates this place now. He goes where the money is, and this is pretty much a money suck. I think that picture out front is the only one I have of the two of them together.” He holds out a plate of assorted breakfast goodies. “Pastry?”

I pluck a blueberry muffin off the plate. “Don’t they like each other?”

He shrugs. “Not even close. They may be twins, but Uncle Robert is so different. A free spirit. He was never around much, even after the Outfitters was started. Then he left two years ago to hike the Appalachian Trail and we haven’t heard from him since. But the guy always does things like that. Crazy things. My dad doesn’t know the first thing about rafting, so I pretty much run this place. I’ve been down the Dead a thousand times. Your boyfriend is one of my best customers. And your cousin. They talk about you all the time.”

“They do?” I blurt, almost spitting out a bit of my muffin. I can’t imagine what they would say, other than She’s not exactly an outdoorsy girl.

He checks a clock on the wall and says, “We’d better get you out there. Bus leaves in five.”

“Okay. Are you going to be on our raft?” I ask. Maybe having The Guy Who Knows Everything About the Dead on my raft would stop my stomach from clenching like it is.

He shakes his head. “There’s a group of novices going out, and they’ll need my help more than you. With Justin and Angela, you’re in good hands. Your guide is Michael. He’s a good guy. Been with us a couple years.”

“Oh,” I say, unable to hide my disappointment. “Is it really wild out there?”

I’m hoping he’ll tell me that no, it’s calm, for some reason they just can’t understand. You can see your reflection in the water. Babies can bathe in it. Instead, he says, “Oh yeah. Wildest of the year is right now. Over seven thousand see-eff-esses.”

“See what?”

“Cubic feet per second. Great time to come up. Great time.”

I gulp. Oh yeah. Great time.

I feel all stiff in this getup; bending my limbs is nearly impossible. When I walk, I’m sure I look like I just peed my pants. We step out to the front and I see through the picture window that a bunch of the rafters are already boarding the white school bus that’s going to take us to put-in.

We’re all alone in the building, so when I hear someone behind me breathe What the devil is that? I turn back to Spiffy and try to figure out what he’s talking about. But he’s just looking at me blankly.

“What the devil is what?” I ask, confused.

He stares at me.

“You just said—”

“I didn’t say anything.” He’s staring at me as if I have a horn protruding from my forehead. Come to think of it, it didn’t sound much like his voice. It had a rougher edge to it, but not only that, there was an accent. Australian, I think. I turn back to where the voice came from, but the room is empty. All I see is that picture of the two Skiffington brothers, smiling together.

“Um, okay,” I say, and then try to cover up by saying, “So, what’s over on the other side of the river?”

He waves his hand over there. “Oh, death. Destruction. All that good stuff.” I guess I must be staring at him, because he says, “I’m kidding. Well, only partly. It’s an old cemetery.”

Ah. Perfect.

He continues, “Haven’t you ever heard of what the west bank means?”

I shake my head.

“Many civilizations used to believe the east bank of a river symbolized birth and renewal. The west bank symbolized death. And so people lived on the east bank. They buried their dead on the west bank.”

I shudder. We really should not be talking about death at a time like this. I’m about to say something like “How interesting,” although really I wish he’d talk about bunnies and rainbows, when it comes again:

What the devil is that?

This time I’m sure of it. It came from the direction of the picture. I stall in the doorway and turn to Spiffy right away, but he’s just jingling his keys and trying to usher me out the door so he can lock up the office. I want to ask him, “You didn’t hear that?” but I already know the answer. He didn’t hear a thing.

Maybe it was just the wind whistling through the trees outside.

But when I climb down the stairs to the gravel driveway, the first thing I notice is that the pines surrounding the Outfitters cabin are completely still. Overhead, a blackbird caws. We may be on the living side of the river, but I can’t stop myself from shivering as I board the bus and we rumble down the dirt road toward the put-in site.