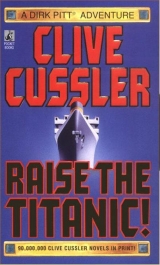

Текст книги "Raise the Titanic"

Автор книги: Clive Cussler

Соавторы: Clive Cussler

Жанр:

Морские приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

"My God!" Woodson whispered. "That's no funnel."

"It looks like a horn," Merker said.

Gunn shook his head. "It's a cornet."

"How can you be sure?" Giordino had left the pilot's console and was peering over Gunn's shoulder through the port.

"I played one in my high-school band."

The others recognized it now, too. They could readily make out the flaring mouth of the bell and behind it, the curved tubes leading to the valves and mouthpiece.

"Judging from the look of it," Merker said, "I'd say it was brass."

"That's why Munk's magnetometer barely picked it up on the graph," Giordino added. "The mouthpiece and the valve pistons are the only parts that contain iron."

"Ah wonder how long it's been down here?" Drummer asked no one in particular.

"It'd be more intriguing to know where it came from," said Merker.

"Obviously thrown overboard from a passing ship," Giordino said carelessly. "Probably by some kid who hated music lessons."

"Maybe its owner is somewhere down here, too." Merker spoke without looking up.

Spencer shivered. "There's a chilling thought for you."

The interior of the Sappho I fell silent.

25

The antique Ford trimotor aircraft, famed in aviation history as the Tin Goose, looked too awkward to fly, and yet she banked as gracefully and majestically as an albatross when she lined up for her final approach to the runway of the Washington National Airport.

Pitt eased back the three throttles and the old bird touched down with all the delicacy of an autumn leaf kissing high grass. He taxied over to one of the NUMA hangars at the north end of the airport, where his waiting maintenance crew chocked the wheels and made the routine throatcutting sign. Flipping off the ignition switches, he watched the silver-bladed propellers gradually slow their revolutions and come to rest, gleaming in the late afternoon sun. Then he removed the headphones, draped them on the control column, undid the latch on his side window and pushed it open.

A bewildered frown slowly creased Pitt's forehead and hung there in the tanned, leathery skin. A man was standing on the asphalt below, frantically waving his hands.

"May I come aboard?" Gene Seagram shouted.

"I'll come down," Pitt yelled back.

"No, please stay where you are."

Pitt shrugged and leaned back in his seat. It took Seagram only a few seconds to climb aboard the trimotor and push open the cockpit door. He wore a stylish tan suit with vest, but his well-tailored appearance was diluted by a sea of wrinkles that creased the material, making it obvious that he hadn't seen a bed for at least twenty-four hours.

"Where did you ever find such a gorgeous old machine?" Seagram asked.

"I ran across it at Keflavik, Iceland," Pitt replied. "Managed to buy it at a fair price and have it shipped back to the States."

"She's a beauty."

Pitt motioned Seagram to the empty copilot's seat. "You sure you want to talk in here? In a few minutes the sun will make this cabin feel like the inside of an incinerator."

"What I have to say won't take long." Seagram eased into the seat and let out a long sigh.

Pitt studied him. He looked like a man who was unwilling and trapped . . . a proud man who had placed himself in an uncompromising position.

Seagram did not face Pitt when he spoke, but stared nervously through the windshield. "I suppose you're wondering what I'm doing here," he said.

"The thought crossed my mind."

"I need your help."

That was it. No mention of the harsh words from the past. No preliminaries; only a straight-to-the-gut request.

Pitt's eyes narrowed. "For some strange reason I had the feeling that my company was about as welcome to you as a dose of syphilis."

"Your feelings, my feelings, they don't matter. What does matter is that your talents are in desperate demand by our government."

"Talents . . . desperate demand . . ." Pitt did not disguise his surprise "You're putting me on, Seagram."

"Believe me, I wish I was, but Admiral Sandecker assures me that you're the only man who stands a remote chance of pulling off a ticklish job."

"What Job?"

"Salvaging the Titanic. "

"Of course! Nothing like a salvage operation to break the monotony of-" Pitt broke off in mid-sentence; his deep green eyes widened and the blood rose to his face. "What ship did you say?" His voice came in a hoarse murmur this time.

Seagram looked at him with an amused expression. "The Titanic. Surely you've heard of it?"

Perhaps ten seconds ticked by in utter silence while Pitt sat there stunned. Then he said, "Do you know what you're proposing?"

"Absolutely."

"It can't be done!" Pitt's expression was incredulous, his voice still the same hoarse murmur. "Even if it were technically possible, and it isn't, it would take hundreds of millions of dollars . . . and then there's the unending legal entanglement with the original owners and the insurance companies over salvage rights."

"There are over two hundred engineers and scientists working on the technical problems at this moment," Seagram explained. "Financing will be arranged through secret government funding. And as far as legal rights go, forget it. Under international law, once a vessel is lost with no hope of recovery, it becomes fair game for anybody who wishes to spend the money and effort on a salvage operation." He turned and stared out the windshield again. "You can't know, Pitt, how important this undertaking is. The Titanic represents much more than treasure or historic value. There is something deep within its cargo holds that is vital to the security of our nation."

"You'll forgive me if I say that sounds a bit farfetched."

"Perhaps, but underneath the flag-waving, the facts hold true."

Pitt shook his head. "You're talking sheer fantasy. The Titanic lies in nearly two and a half miles of water. The pressure at those depths runs several thousand pounds to the square inch, Mr. Seagram; not square foot or square yard, but square inch. The difficulties and barriers are staggering. No one has ever seriously attempted to raise the Andrea Doria or the Lusitania from the bottom . . and they both lie only three hundred feet from the surface."

"If we can put men on the moon, we can bring the Titanic up to the sunlight again," Seagram argued.

"There's no comparison. It took a decade to set a four-ton capsule on lunar soil. Lifting forty-five thousand tons of steel is a different proposition. It may take months just to find her."

"The search is already under way."

"I heard nothing-"

"About a search effort?" Seagram finished. "Not likely that you should. Until the operation becomes unwieldy in terms of security, it will remain secret. Even your assistant special projects director, Albert Giordano-"

"Giordino."

"Yes, Giordino, thank you. He is at this very moment piloting a search probe across the Atlantic sea floor in total ignorance of his true mission."

"But the Lorelei Current Expedition . . . the Sappho I's original mission was to trace a deep ocean current."

"A timely coincidence. Admiral Sandecker was able to order the submersible into the area of the Titanic's last known position barely hours before the sub was scheduled to surface."

Pitt turned and stared at a jet airliner that was lifting from the airport's main runway. "Why me? What have I done to deserve an invitation to what has to be the biggest hare-brained scheme of the century?"

"You are not simply to be a guest, my dear Pitt. You are to command the overall salvage operation."

Pitt regarded Seagram grimly. "The question still stands. Why me?"

"Not a selection that excites me, I assure you," Seagram said. "However, since the National Underwater and Marine Agency is the nation's largest acknowledged authority on oceanographic science, and since the leading experts on deep-water salvage are members of their staff, and since you are the agency's Special Projects Director, you were elected."

"The fog begins to lift. It's a simple case of my being in the wrong occupation at the wrong time."

"Read it as you will," Seagram said wearily. "I must admit, I found your past record of bringing incredibly difficult projects to successful conclusions most impressive." He pulled out a handkerchief and dabbed his forehead. "Another factor that weighed heavily in your favor, I might add, is that you are considered somewhat of an expert on the Titanic. "

"Collecting and studying Titanic memorabilia is a hobby with me, nothing more. It hardly qualifies me to oversee her salvage."

"Nonetheless, Mr. Pitt, Admiral Sandecker tells me you are, to use his words, a genius at handling men and coordinating logistics." He gazed over at Pitt, his eyes uncertain. "Will you take the job?"

"You don't think I can pull it off, do you, Seagram?"

"Frankly, no. But when one dangles over the cliff by a thread, one has little say about who comes to the rescue."

A faint smile edged Pitt's lips. "Your faith in me is touching."

"Well?"

Pitt sat lost in thought for several moments. Finally, he gave an almost imperceptible nod and looked squarely into Seagram's eyes. "Okay, my friend, I'm your boy. But don't count you're chickens until that rusty old hulk is moored to a New York dock. There isn't a bet-maker in Las Vegas who'd waste a second computing odds on this crazy escapade. When we find the Titanic, if we find the Titanic, her hull nay be too far gone to raise. But then nothing is absolutely impossible, and though I can't begin to guess what it is that's so valuable to the government that warrants the effort, I'll try, Seagram. Beyond that, I promise nothing."

Pitt broke into a wide grin and climbed from the pilot's seat. "End of speech. Now then, let's get out of this hot box and find a nice cool air-conditioned cocktail lounge where you can buy me a drink. It's the least you can do after pulling off the con job of the year."

Seagram just sat there, too drained to do anything except shrug in helpless acquiescence.

26

At first John Vogel treated the cornet as simply another restoration job. There was no rarity suggested by its design. There was nothing exceptional about its construction that would excite a collector. At the moment it could excite nobody. The valves were corroded and frozen closed; the brass was discolored by an odd sort of accumulated grime; and a foul, fishlike odor emanated from the mud that clogged the interior of its tubes.

Vogel decided the cornet was beneath him; he would turn it over to one of his assistants for the restoration. The exotics, those were the instruments that Vogel loved to bring back to their original newness the ancient Chinese and Roman trumpets, with the long, straight tubes and the ear-piercing tones; the battered old horns of the early jazz greats; the instruments with a piece of history attached-these, Vogel would repair with the patience of a watchmaker, toiling with exacting craftsmanship until the piece gleamed like new and played brilliantly clear tones.

He wrapped the cornet in an old pillowcase and set it against the far wall of his office.

The Executone on his desk uttered a soft bong. "Yes, Mary, what is it?"

"Admiral James Sandecker of the National Underwater and Marine Agency is on the phone." His secretary's voice scratched over the intercom like fingernails over a blackboard. "He says it's urgent."

"Okay, put him on." Vogel lifted the telephone. "John Vogel here."

"Mr. Vogel, this is James Sandecker."

The fact that Sandecker had dialed his own call and didn't bluster behind his title impressed Vogel.

"Yes, Admiral, what can I do for you?"

"Have you received it yet?"

"Have I received what?"

"An old bugle."

"Ah, the cornet," Vogel said. "I found it on my desk this morning with no explanation. I assumed it was a donation to the museum."

"My apologies, Mr. Vogel. I should have forewarned you, but I was tied up."

A straightforward excuse.

"How can I help you, Admiral?"

"I'd be grateful if you could study the thing and tell me what you know about it. Date of manufacture and so on."

"I'm flattered, sir. Why me?"

"As chief curator for the Washington Museum's Hall of Music, you seemed the logical choice. Also, a mutual friend said that the world lost another Harry James when you decided to become a scholar."

My God, Vogel thought, the President. Score another point for Sandecker. He knew the right people.

"That's debatable," Vogel said. "When would you like my report?"

"As soon as it's convenient for you."

Vogel smiled to himself. A polite request deserved extra effort. "The dipping process to remove the corrosion is what takes time. With luck, I should have something for you by tomorrow morning."

"Thank you, Mr. Vogel," Sandecker said briskly. "I'm grateful."

"Is there any information concerning how or where you found the cornet that might help me?"

"I'd rather not say. My people would like your opinions entirely without prompting or direction on our part."

"You want to compare my findings with yours, is that it?"

Sandecker's voice carried sharply through the earpiece. "We want you to confirm our hopes and expectations, Mr. Vogel, nothing more."

"I shall do my best, Admiral. Good-by."

"Good luck."

Vogel sat for several minutes staring at the pillowcase in the corner, his hand resting on the telephone. Then he pressed the Executone. "Mary, hold all calls for the rest of the day, and send out for a medium pizza with Canadian bacon and a half gallon of Gallo burgundy."

"You going to lock yourself in that musty old workshop again?" Mary's voice scratched back.

"Yes," Vogel sighed. "It's going to be a long day."

First, Vogel took several photos of the cornet from different angles. Then he noted the dimensions, general condition of the visible parts, and the degree of tarnish and foreign matter that coated the surfaces, recording each observation in a large notebook. He regarded the cornet with an increased level of professional interest. It was a quality instrument; the brass was of good commercial grade, and the small bores of the bell and the valves told him that it was manufactured before 1930. He discovered that what he had thought to be corrosion was only a hard crust of mud that flaked away under light pressure from a rubber spoon.

Next, he soaked the instrument in diluted Calgon water softener, gently agitating the liquid and changing the tank every so often to drain away the dirt. By midnight, he had the cornet completely disassembled. Then he started the tedious job of swabbing the metal surfaces with a mild solution of chromic acid to bring out the shine of the brass. Slowly, after several rinsings, an intricate scroll pattern and several ornately scripted letters began to appear on the bell.

"By God!" Vogel blurted aloud. "A presentation model."

He picked up a magnifying glass and studied the writing. When he set the glass down and reached for a telephone, his hands were trembling.

27

At precisely eight o'clock, John Vogel was ushered into Sandecker's office on the top floor of the ten-story solar-glassed building that housed the national headquarters of NUMA. His eyes were bloodshot and he made no effort to conceal a yawn.

Sandecker came out from behind his desk and shook Vogel's hand. The short, banty admiral had to lean backward and look up to meet the eyes of his visitor. Vogel was six foot five, a kindly faced man with puffs of unbrushed white hair edging a bald head. He gazed through brown Santa Claus eyes, and flashed a warm smile. His coat was neatly pressed, but his pants were rumpled and stained with a myriad of blotches below the knees. He smelled like a wino.

"Well," Sandecker greeted him. "It's a pleasure to meet you."

"The pleasure is mine, Admiral." Vogel set a black trumpet case on the carpet. "I'm sorry I appear so slovenly."

"I was going to say," Sandecker answered, "it seems you've had a difficult night."

"When one loves one's work, time and inconvenience have little meaning."

"True." Sandecker turned and nodded to a little gnomelike man who was standing in one corner of the office. "Mr. John Vogel, may I present Commander Rudi Gunn."

"Of course, Commander Gunn," Vogel said, smiling. "I was one of the many millions who followed your Lorelei Current Expedition every day in the newspapers. You're to be congratulated, Commander. It was a great achievement."

"Thank you," Gunn said.

Sandecker gestured to another man sitting on the couch. "And my Special Projects Director, Dirk Pitt."

Vogel nodded at the swarthy face that crinkled into a smile. "Mr. Pitt."

Pitt rose and nodded back. "Mr. Vogel."

Vogel sat down and pulled out a battered old pipe. "Mind if I smoke?"

"Not at all." Sandecker lifted one of his Churchill cigars out of a humidor and held it up. "I'll join you."

Vogel puffed the bowl into life and then sat back and said, "Tell me, Admiral, was the cornet discovered on the bottom of the North Atlantic?"

"Yes, just south of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland." He stared at Vogel speculatively. "How did you guess that?"

"Elementary deduction."

"What can you tell us about it?"

"A considerable amount, actually. To begin with, it is a high-quality instrument, crafted for a professional musician."

"Then it's not likely it was owned by an amateur player?" Gunn said, remembering Giordino's words on the Sappho I.

"No," Vogel said flatly. "Not likely."

"Could you determine the time and place of manufacture?" Pitt asked.

"The approximate month was either October or November. The exact year was 1911. And it was manufactured by a very reputable and very fine old British firm by the name of Boosey-Hawkes."

There was respect written in Sandecker's eyes. "You've done a remarkable job, Mr. Vogel. Quite frankly, we doubted whether we would ever know the country of origin, much less the actual manufacturer."

"No investigative brilliance on my part, I assure you," Vogel said. "You see, the cornet was a presentation model"

"A presentation model?"

"Yes. Any metal product that takes a high degree of craftsmanship to construct, and is highly prized as a possession, is often engraved to commemorate an unusual event or outstanding service."

"A common practice among gunmakers," Pitt commented.

"And also creators of fine musical instruments. In this instance, it was presented to an employee by his company in recognition of his service. The presentation date, the manufacturer, the employee, and his company are all beautifully engraved on the cornet's bell."

"You can actually tell who owned it?" Gunn asked. "The engraving is readable?"

"Oh my, yes." Vogel bent down and opened the case. "Here, you can read it for yourself."

He set the cornet on Sandecker's desk. The three men stared at it silently for a long time-a gleaming instrument whose golden surface reflected the morning sun that was streaming in the window. The cornet looked brand-new. Every inch was buffed to a high shine and the intricate engraving of sea waves that curled around the tube and bell were as clear as the day they were etched. Sandecker gazed over the cornet at Vogel, his brows lifted in doubt.

"Mr. Vogel, I think you fail to see the seriousness of the situation. I don't care for jokes."

"I admit," Vogel snapped back, "that I fail to see the seriousness of the situation. What I do see is a moment of tremendous excitement. And believe me, Admiral, this is no joke. I have spent the best part of the last twenty-four hours restoring your discovery." He threw a bulky folder on the desk. "Here is my report, complete with photographs and my step-by-step observations during the restoration procedure. There are also envelopes containing the different types of residue and mud that I removed, and also the parts that I replaced. I overlooked nothing."

"I apologize," Sandecker said. "Yet it seems inconceivable that the instrument we sent you yesterday, and the instrument on the desk are one and the same." Sandecker paused and exchanged glances with Pitt. "You see, we . . ."

". . . thought the cornet had rested on the sea bottom for a long time," Vogel finished the sentence. "I'm fully aware of what you're driving at, Admiral. And I confess I'm at a loss as to the instrument's remarkable condition, too. I've worked on any number of musical instruments which have been immersed in salt water for only three to five years that were in far worse shape than this one. I'm not an oceanographer so the solution to the puzzle eludes me. However, I can tell you to the day how long that cornet has been beneath the sea and how it came to be there."

Vogel reached over and picked up the horn. Then he slipped on a pair of rimless glasses and began reading aloud. "Presented to Graham Farley in sincere appreciation for distinguished performance in the entertainment of our passengers by the grateful management of the White Star Line." Vogel removed his glasses and smiled benignly at Sandecker. "When I discovered the words White Star Line, I got a friend out of bed early this morning to do a bit of research at the Naval Archives. He called only a half hour before I left for your office." Vogel paused to remove a handkerchief from his pocket and blew his nose. "It seems Graham Farley was a very popular fellow throughout the White Star Line. He was solo cornetist for three years on one of their vessels . . . I believe it was called the Oceanic. When the company's newest luxury liner was about to set sail on her maiden voyage, the management selected the outstanding musicians from their other passenger ships and formed what was considered at the time the finest orchestra on the seas. Graham, of course, was one of the first musicians chosen. Yes, gentlemen, this cornet has rested under the Atlantic Ocean for a very long time . . . because Graham Farley was playing it on the morning of April 15, 1912, when the waves closed over him and the Titanic. "

The reactions to Vogel's sudden revelation were mixed. Sandecker's face turned half-somber, half-speculative; Gunn's went rigid; while Pitt's expression was one of casual interest. The silence in the room became intense as Vogel stuffed his glasses back in a breast pocket.

"Titanic." Sandecker repeated the word slowly, like a man savoring a beautiful woman's name. He gazed penetratingly at Vogel, wonder mingled with doubt still mirrored in his eyes. "It's incredible."

"A fact nonetheless," Vogel said casually. "I take it, Commander Gunn, that the cornet was discovered by the Sappho I?"

"Yes, near the end of the voyage."

"It would appear that your undersea expedition stumbled on a bonus. A pity you didn't run onto the ship herself."

"Yes, a pity," Gunn said, avoiding Vogel's eyes.

"I'm still at a loss as to the instrument's condition," Sandecker said. "I hardly expected a relic sunk in the sea for seventy-five years to come up looking little the worse for wear."

"The lack of corrosion does pose an interesting question," Vogel replied. "The brass most certainly would weather well, but, strangely, the parts containing ferrous metals survived in a remarkable virgin state. The original mouthpiece, as you can see, is near-perfect."

Gunn was staring at the cornet as if it was the holy grail. "Will it still play?"

"Yes," Vogel answered. "Quite beautifully, I should think."

"You haven't tried it?"

"No . . . I have not." Vogel ran his fingers reverently over the cornet's valves. "Up to now, I have always tested every brass instrument my assistants and I have restored for its brilliance of tone. This time I cannot."

"I don't understand," Sandecker said.

"This instrument is a reminder of a small, but courageous act performed during the worst sea tragedy in man's history," Vogel replied. "It takes very little imagination to envision Graham Farley and his fellow musicians while they soothed the frightened ship's passengers with music, sacrificing all thought of their own safety, as the Titanic settled into the cold sea. The cornet's last melody came from the lips of a very brave man. I feel it would border on the sacrilegious for anyone else ever to play it again."

Sandecker stared at Vogel, examining every feature of the old man's face as if he were seeing it for the first time.

"'Autumn'," Vogel was murmuring, almost rambling to himself. "'Autumn', an old hymn. That was the last melody Graham Farley played on his cornet."

"Not 'Nearer My God to Thee'?'' Gunn spoke slowly.

"A myth," said Pitt. "'Autumn' was the final tune that was heard from the Titanic's band just before the end."

"You seem to have made a study of the Titanic," Vogel said.

"The ship and her tragic fate is like a contagious disease," Pitt replied. "Once you become interested, the fever is tough to break."

"The ship itself holds little attraction for me. But as a historian of musicians and their instruments, the saga of the Titanic's band has always gripped my imagination." Vogel set the cornet in the case, closed the lid, and passed it across the desk to Sandecker. "Unless you have more questions, Admiral, I'd like to grab a fattening breakfast and fall into bed. It was a difficult night."

Sandecker stood. "We're in your debt, Mr. Vogel."

"I was hoping you might say that," the Santa Claus eyes twinkled slyly. "There is a way you can repay me."

"Which is?"

"Donate the cornet to the Washington Museum. It would be the prize exhibit of our Hall of Music."

"As soon as our lab people have studied the instrument and your report, I'll send it over to you."

"On behalf of the museum's directors, I thank you."

"Not as a gift donation, however."

Vogel stared uncertainly at the Admiral.

"I don't follow."

Sandecker smiled. "Let's call it a permanent loan. That will save hassle in case we ever have to borrow it back temporarily."

"Agreed."

"One more thing," Sandecker said. "Nothing has been mentioned to the press about the discovery. I'd appreciate it if you went along with us for the time being."

"I don't understand your motives, but of course I'll comply."

The towering curator bid his farewells and departed.

"Damn!" Gunn blurted out a second after the door closed. "We must have passed within spitting distance of the Titanic's hulk."

"You were certainly in the ball park," Pitt agreed. "The Sappho's sonar probed a radius of two hundred yards. The Titanic must have rested just outside the fringe of your range."

"If only we'd had more time. If only we'd known what in hell we were looking for."

"You forget," Sandecker said, "that testing the Sappho I and conducting experiments on the Lorelei Current were your primary objectives, and on that you and your crew did one hell of a job. Oceanographers will be sifting the data you brought back on deepwater currents for the next two years. My only regret is that we couldn't let you in on what we were up to, but Gene Seagram and his security people insist that we keep a tight lid on any information regarding the Titanic until we're far along on the salvage operation."

"We won't be able to keep it quiet for long," Pitt said. "All the news media in the world will soon smell a story on the greatest historical find since the opening of King Tut's tomb."

Sandecker rose from behind his desk and walked over to the window. When he spoke, his words came very softly, sounding almost as if they were carried over a great distance by the wind. "Graham Farley's cornet."

"Sir?"

"Graham Farley's cornet," Sandecker repeated wistfully. "If that old horn is any indication, the Titanic may be sitting down there in the black abyss as pretty and preserved as the night she sank."

28

To a chance observer standing on the shore or to anyone out for a leisurely cruise up the Rappahannock River, the three men slouched in a dilapidated old rowboat looked like a trio of ordinary weekend fishermen. They were dressed in faded shirts and dungarees, and sported hats festooned with the usual variety of hooks and flies. It was a typical scene, down to the sixpack of beer trapped in a fishnet dangling in the water beside the boat.

The shortest of the three, a red-haired, pinched-faced man, lay against the stern and seemed to be dozing, his hands loosely gripped around a fishing pole that was attached to a red and white cork bobbing a bare two feet from the boat's waterline. The second man simply slouched over an open magazine, while the third fisherman sat upright and mechanically went through the motions of casting a silver lure. He was large; with a well-fed stomach that blossomed through his open shirt, and he gazed through lazy blue eyes set in a jovial round face. He was the perfect image of everyone's kindly old grandfather.

Admiral Joseph Kemper could afford to look kindly. When you wielded the almost incredible authority that he did, you didn't have to squint through hypnotic eyes or belch fire like a dragon. He looked down and offered a benevolent expression to the man who was dozing.

"It strikes me, Jim, that you're not deeply into the spirit of fishing."

"This has to be the most useless endeavor ever devised by man," Sandecker replied.

"And you, Mr. Seagram? You haven't dropped a hook since we anchored."

Seagram peered at Kemper over the magazine. "If a fish could survive the pollution down there, Admiral, he'd have to look like a mutant out of a low-budget horror movie, and taste twice as bad."

"Since it was you gentlemen who invited me here," Kemper said, "I'm beginning to suspect a devious motive."

Sandecker neither agreed nor disagreed. "Just relax and enjoy the great outdoors, Joe. Forget for a few hours that you're the Navy's Chief of Staff."