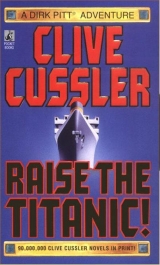

Текст книги "Raise the Titanic"

Автор книги: Clive Cussler

Соавторы: Clive Cussler

Жанр:

Морские приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Raise The Titanic

By

Clive Cussler

Foreword

When Dirk Pitt salvaged the Titanic from the pages of a typewriter set in a damp corner of an unfinished basement, the legendary ocean liner was still ten years away from actual discovery. The year was 1975 and Raise the Titanic became the fourth book in Pitt's underwater adventures. Then, no one was inspired to spend the immense effort in time and money for a search operation. But after the book was published and the movie produced, a renewed tidal wave of interest swept America and Europe. At least five expeditions were launched to look for the wreck.

My original inspiration was based on fantasy and a desire to see the world's most famous ship brought up from the seabed and towed into New York Harbor, completing her maiden voyage begun three quarters of a century before. Fortunately, it was a fantasy shared by millions of her devoted fans.

Now, 73 years after she slipped into the silence of the black abyss, cameras have finally revealed her open grave.

Fiction has become fact.

Pitt's description of her in the story pretty well matches what the robot cameras recorded shortly after she was found through the miracle of sidescan sonar. Aside from her structural damage, sustained during her 13,000-foot plunge to the bottom, she suffers little from sea growth and corrosion. Even the wine bottles and silver service that spilled out on the silt appear pristine.

Will the Titanic ever be raised?

It is unlikely. A total salvage operation would nearly equal the cost of the Apollo man-on-the-moon project. Soon, however, we can expect to see manned submersibles circling her hulk in search of her treasure in artifacts, while teams of American and British attorneys roll up their sleeves for long courtroom battles over her possession.

Pitt has always looked in the future and found it full of excitement and adventure. In the nineteen seventies he was a man of the eighties. Now he is a man of the nineties. Like a scout out for a wagon train. Pitt looks over the next hill and tells us what's there. He sees what we'd all like to see in our imaginations.

That's why no one could have been more delighted than I when it was announced that the Titanic had been found.

I knew that Pitt had seen her first.

April 1912

PRELUDE

The man on Deck A, Stateroom 33, tossed and turned in his narrow berth, the mind behind his sweating face lost in the depths of a nightmare. He was small, no more than two inches over five feet, with thinning white hair and a bland face, whose only imposing feature was a pair of dark, bushy eyebrows. His hands lay entwined on his chest, his fingers twitching in a nervous rhythm. He looked to be in his fifties. His skin had the color and texture of a concrete sidewalk, and the lines under his eyes were deeply etched. Yet he was only ten days shy of his thirty-fourth birthday.

The physical grind and the mental torment of the last five months had exhausted him to the ragged edge of madness. During his waking hours, he found his mind wandering down vacant channels, losing all track of time and reality. He had to remind himself continually where he was and what day it was. He was going mad, slowly but irrevocably mad, and the worst part of it was that he knew he was going mad.

His eyes fluttered open and he focused them on the silent fan that hung from the ceiling of his stateroom. His hands traveled over his face and felt the two-week growth of beard. He didn't have to look at his clothes; he knew they were soiled and rumpled and stained with nervous sweat. He should have bathed and changed after he'd boarded the ship, but, instead, he'd taken to his berth and slept a fearful, obsessed sleep off and on for nearly three days.

It was late into Sunday evening, and the ship wasn't due to dock in New York until early Wednesday morning, slightly more than fifty hours hence.

He tried to tell himself he was safe now, but his mind refused to accept it, in spite of the fact that the prize that had cost so many lives was absolutely secure. For the hundredth time he felt the lump in his vest pocket. Satisfied that the key was still there, he rubbed a hand over his glistening forehead and closed his eyes once more.

He wasn't sure how long he'd dozed. Something had jolted him awake. Not a loud sound or a violent movement, it was more like a trembling motion from his mattress and a strange grinding noise somewhere far below his starboard stateroom. He rose stiffly to a sitting position and swung his feet to the floor. A few minutes passed and he sensed an unusual, vibrationless quiet. Then his befogged mind grasped the reason. The engines had stopped. He sat there listening, but the only sounds came from the soft joking of the stewards in the passageway, and the muffled talk from the adjoining cabins.

An icy tentacle of uneasiness wrapped around him. Another passenger might have simply ignored the interruption and quickly gone back to sleep, but he was within an inch of a mental breakdown, and his five senses were working overtime at magnifying every impression. Three days locked in his cabin, neither eating nor drinking, reliving the horrors of the past five months, served only to stoke the fires of insanity behind his rapidly degenerating mind.

He unlocked the door and walked unsteadily down the passageway to the grand staircase. People were laughing and chattering on their way from the lounge to their staterooms. He looked at the ornate bronze clock which was flanked by two figures in bas-relief above the middle landing of the stairs. The gilded hands read 1151.

A steward, standing alongside an opulent lamp standard at the bottom of the staircase, stared disdainfully up at him, obviously annoyed at seeing so shabby a passenger wandering the first-class accommodations, while all the others strolled the rich Oriental carpets in elegant evening dress.

"The engines . . . they've stopped," he said thickly.

"Probably for a minor adjustment, sir," the steward replied. "A new ship on her maiden voyage and all. There's bound to be a few bugs to iron out. Nothing to worry about. She's unsinkable, you know."

"If she's made out of steel, she can sink." He massaged his bloodshot eyes. "I think I'll take a look outside."

The steward shook his head. "I don't recommend it, sir. It's frightfully cold out there."

The passenger in the wrinkled suit shrugged. He was used to the cold. He turned, climbed one flight of stairs and stepped through a door that led to the starboard side of the boat deck. He gasped as though he'd been stabbed by a thousand needles. After lying for three days in the warm womb of his stateroom, he was rudely shocked by the thirty-one-degree temperature. There was not the slightest hint of a breeze, only a biting, motionless cold that hung from the cloudless sky like a shroud.

He walked to the rail and turned up the collar of his coat. He leaned over but saw only the black sea, calm as a garden pond. Then he looked fore and aft. The Boat Deck from the raised roof over the first-class smoking room to the wheelhouse forward of the officers' quarters was totally deserted. Only the smoke drifting lazily from the forward three of the four huge yellow and black funnels, and the lights shining through the windows of the lounge and reading room revealed any involvement with human life.

The white froth along the hull diminished and turned black as the massive vessel slowly lost her headway and drifted silently beneath the endless blanket of stars. The ship's purser came out of the officers' mess and peered over the side.

"Why did we stop?"

"We've struck something," the purser replied without turning.

"Is it serious?"

"Not likely, sir. If there's any leakage, the pumps should handle it."

Abruptly, an ear-shattering roar that sounded like a hundred Denver and Rio Grande locomotives thundering through a tunnel at the same time erupted from the eight exterior exhaust ducts. Even as he put his hands to his ears, the passenger recognized the cause. He had been around machinery long enough to know that the excess steam from the ship's idle reciprocating engines was blowing off through the bypass valves. The terrific blare made further speech with the purser impossible. He turned away and watched as other crew members appeared on the Boat Deck. A terrible dread spread through his stomach as he saw them begin stripping off the lifeboat covers and clearing away the lines to the davits.

He stood there for nearly an hour while the din from the exhaust ducts died slowly in the night. Clutching the handrail, oblivious to the cold, he barely noticed the small groups of passengers who had begun to wander the Boat Deck in a strange, quiet kind of confusion.

One of the ship's junior officers came past. He was young, in his early twenties, and his face had the typically British milky-white complexion and the typically British bored-with-it-all expression. He approached the man at the railing and tapped him on the shoulder.

"Beg your pardon, sir. But you must get your life jacket on."

The man slowly turned and stared. "We're going to sink, aren't we?" he asked hoarsely.

The officer hesitated a moment, then nodded. "She's taking sea faster than the pumps can keep up."

"How long do we have?"

"Hard to say. Maybe another hour if the water stays clear of the boilers."

"What happened? There was no other ship nearby. What did we collide with?"

"Iceberg. Slashed our hull. Damnable bit of bloody luck."

He grasped the officer's arm so hard the young man winced. "I must get into the cargo hold."

"Little chance of that, sir. The mail room on F Deck is flooding and the luggage is already floating down in the hold."

"You must guide me there."

The officer tried to shake his arm loose, but it was held like a vise. "Impossible! My orders are to see to the starboard lifeboats."

"Some other officer can man the boats," the passenger said tonelessly. "You're going to show me the way to the cargo hold."

It was then that the officer noticed two discomforting things. First, the twisted, insane look on the passenger's face, and, second, the muzzle of the gun that was pressing against his genitals.

"Do as I ask," the man snarled, "if you wish to see grandchildren."

The officer stared dumbly at the gun and then looked up. Something inside him was suddenly sick. There was no thought of argument or resistance. The reddened eyes that burned into his, burned from within the depths of insanity.

"I can only try."

"Then try!" the passenger snarled. "And no tricks. I'll be at your back all the way. One stupid mistake and I'll shoot your spine in two at the base."

Discreetly, he shoved the gun into a coat pocket, keeping the barrel nudged against the officer's back. They made their way without difficulty through the milling throng of people who now cluttered the Boat Deck. It was a different ship now. No laughter or gaiety, no class distinction; the wealthy and the poor were joined by the common bond of fear. The stewards were the only ones smiling and making small talk as they handed out ghost-white life preservers.

The distress rockets soared into the air, looking small and vain under the smothering blackness, their burst of white sparkles seen by no one except those aboard the doomed ship. It provided an unearthly backdrop for the heartrending good-byes, the forced expressions of hope in the men's eyes as they tenderly lifted their women and children into the lifeboats. The terrible unreality of the scene was heightened as the ship's eight-piece band assembled on the Boat Deck, incongruous with their instruments and pale life jackets. They began to play Irving Berlin's "Alexander's Ragtime Band."

The ship's officer, prodded by the gun, struggled down the main stairway against the wave of passengers who were surging up toward the lifeboats. The low angle of the bow was becoming more pronounced. Going down the steps, their stride was off-balance. At B Deck they commandeered an elevator and rode it down to D Deck.

The young officer turned and studied the man whose strange whim had inexorably bound him tighter in the grip of certain death. The lips were drawn back tightly over the teeth, the eyes glassy with a faraway look. The passenger glanced up and saw the officer staring at him. For a long moment their eyes locked.

"Don't worry."

"Bigalow, sir."

"Don't worry, Bigalow. You'll make it before she goes."

"What section of the cargo hold do you want?"

"The ship's vault in number one cargo hold, G Deck."

"G Deck must surely be under water by now."

"We'll only know when we get there, won't we?" The passenger motioned with the gun in his coat pocket as the elevator doors opened. They moved out and pushed their way through the crowd.

Bigalow tore off his life belt and ran around the staircase leading to E Deck. There he stopped and looked down and saw the water crawling upward, inching its relentless path up the steps. Some of the lights still burned under the cold green water, giving off a haunting, distorted glow.

"It's no use. You can see for yourself."

"Is there another way?"

"The watertight doors were closed right after the collision. We might make it down one of the escape ladders."

"Then keep going."

The journey along the circuitous alleyways went rapidly through the unending steel labyrinth of passages and ladder tunnels. Bigalow halted and lifted a round hatch cover and peered into the narrow opening. Surprisingly, the water on the cargo deck beneath was only two feet deep.

"No hope," he lied. "It's flooded."

The passenger roughly shoved the officer to one side and looked for himself.

"It's dry enough for my purpose," he said slowly. He waved the gun at the hatch. "Keep going."

The overhead electric lights were still burning in the hold as the two men sloshed their way toward the ship's strong room. The dim rays glinted off the brass of a giant Renault town car blocked to the deck.

Both of them stumbled and fell in the icy water several times, numbing their bodies with the cold. Staggering like drunken men, they reached the vault at last. It was a cube in the middle of the cargo compartment. It measured eight feet by eight feet; its sturdy walls were constructed of twelve inch-thick Belfast steel.

The passenger produced a key from his vest pocket and inserted it in the slot. The lock was new and stiff, but finally the tumblers gave with an audible click. He pushed the heavy door open and stepped into the vault. Then he turned and smiled for the first time. "Thanks for your help, Bigalow. You'd better head topside. There's still time for you."

Bigalow looked puzzled. "You're staying?"

"Yes, I'm staying. I've murdered eight good and true men. I can't live with that." It was said flatly. The tone final. "It's over and done with. Everything."

Bigalow tried to speak, but the words would not come.

The passenger nodded in understanding and began pulling the door closed behind him.

"Thank God for Southby," he said.

And then he was gone, swallowed up in the black interior of the vault.

Bigalow survived.

He won his race with the rising water and managed to reach the Boat Deck and throw himself over the side only seconds before the ship took her plunge.

As the bulk of the great ocean liner sank from sight, her red pennant with the white star that had been hanging limply, high on the aft mast peak under the dead calm of the night, suddenly unfurled when it touched the sea, as though in final salute to the fifteen hundred men, women, and children who were either dying of exposure or drowning in the frigid waters over the grave.

Blind instinct clutched at Bigalow and he reached out and seized the pennant as it slipped past. Before his mind could focus, before he knew the full danger of his foolhardy act, he found himself being pulled beneath the water. Yet he stubbornly held on, refusing to release his grip. He was nearly twenty feet below the surface when at last the pennant's grommets tore from the halyard and the prize was his. Only then did he struggle upward through the liquid blackness. After what seemed to him an eternity, he broke into the night air again, thankful that the expected suction from the sinking ship had not gotten him.

The twenty-eight-degree water nearly killed him. Given another ten minutes in its freezing grip, he would have simply been one more statistic of that terrible tragedy.

A rope saved him; his hand brushed against and grabbed a trailing rope attached to a capsized boat. With the last ounce of his ebbing strength, he pulled his nearly frozen body on board and shared with thirty other men the numbing ache of the cold until they were rescued by another ship four hours later.

The pitiful cries of the hundreds who died would forever linger in the minds of those who survived. But as he clung to the overturned, partly submerged lifeboat, Bigalow's thoughts were on another memory the strange man sealed forever in the ship's vault.

Who was he?

Who were the eight men he claimed to have murdered?

What was the secret of the vault?

They were questions that were to haunt Bigalow for the next seventy-six years, right up to the last few hours of his life.

THE SICILIAN PROJECT

July 1987

1

The President swiveled in his chair, clasped his hands behind his head, and stared unseeing out of the window of the Oval Office and cursed his lot. He hated his job with a passion he hadn't thought possible. He had known the exact moment the excitement had gone out of it. He had known it the morning be had found it hard to rise from bed. That was always the first sign. A dread of beginning the day.

He wondered for the thousandth time since taking office why he had struggled so hard and so long for the damned thankless job anyway. The price had been painfully his. His political trail was littered with the bones of lost friends and a broken marriage. And, he'd no sooner taken the oath of office when he had found his infant administration staggered by a Treasury Department scandal, a war in South America, a nationwide airlines strike, and a hostile Congress that had come to mistrust whoever resided in the White House. He threw in an extra curse for Congress. Its members had overridden his last two vetoes and the news didn't sit well with him.

Thank God, be would escape the bullshit of another election. How he'd managed to win two terms still mystified him. He had broken all the political taboos ever laid down for a successful candidate. Not only was he a divorced man but he was not a churchgoer, smoked cigars in public, and sported a large mustache besides. He had campaigned by ignoring his opponents and by hitting the voters solidly between the eyes with tough talk. And they had loved it. Opportunely, he had come along at a time when the average American was fed up with goody-goody candidates who smiled big and made love to the TV cameras, and who spoke trite, nothing sentences that the press couldn't twist or find hidden meanings to invent between the nouns.

Eighteen more months and his second term in office would be over. It was the one thought that kept him going. His predecessor had accepted the post of head regent at the University of California. Eisenhower had withdrawn to his farm in Gettysburg, and Johnson to his ranch in Texas. The President smiled to himself. None of that elder-statesman on-the-sidelines crap for him. His plans called for self-exile to the South Pacific on a forty-foot ketch. There he would ignore every damned crisis that stirred the world while sipping rum and eyeing any pug-nosed, balloon-chested native girls who wandered within view. He closed his eyes and almost had the vision in focus when his aide eased open the door and cleared his throat.

"Excuse me, Mr. President, but Mr. Seagram and Mr. Donner are waiting."

The President swiveled back to his desk and ran his hands through a patch of thick silver-tinted hair. "Okay, send them in."

He brightened visibly. Gene Seagram and Mel Donner enjoyed immediate access to the President at any time, day or night. They were the chief evaluators for the Meta Section, a group of scientists who worked in total secrecy, researching projects that were as yet unheard of-projects that attempted to leapfrog current technology by twenty to thirty years.

Meta Section was the President's own brainchild. He had conceived it during his first year in office, connived and manipulated the unlimited secret funding, and personally recruited the small group of brilliant and dedicated men who comprised its core. He took great unadvertised pride in it. Even the CIA and the National Security Agency knew nothing of its existence. It had always been his dream to back a team of men who could devote their skills and talents to impossible schemes, fantasy schemes with one chance in a million for success. The fact that Meta Section was still batting zero five years after its inception bothered his conscience not at all.

There was no hand shaking, only cordial hello's. Then Seagram unlatched a battered leather briefcase and withdrew a folder stuffed with aerial photographs. He laid the pictures on the President's desk and pointed at several circled areas that were marked on transparent overlays.

"The mountain region on the upper island of Novaya Zemlya, north of the Russian mainland. All indications from our satellite sensors pinpoint this area as a slim possibility."

"Damn?" the President muttered softly. "Every time we discover something like this, it has to sit in the Soviet Union or in some other untouchable location." He scanned the photographs and then turned his eyes to Donner. "The earth is a big place. Surely there must be other promising areas?"

Donner shook his head. "I'm sorry, Mr. President, but geologists have been searching for byzanium ever since Alexander Beesley discovered its existence in 1902. To our knowledge, none has ever been found in quantity."

"It's radioactivity is so extreme," Seagram said, "it has long vanished from the continents in anything more than very minute trace amounts. The few bits and pieces we've gathered on this element have been gleaned from small, artificially prepared particles."

"Can't you build a supply through artificial means?" the President asked.

"No, sir," Seagram replied. "The longest-lived particle we managed to produce with a high-energy accelerator decayed in less thaw two minutes."

The President sat back and stared at Seagram. "How much of it do you need to complete your program?"

Seagram looked to Donner, then at the President. "Of course you realize, Mr. President, we're still in a speculative stage . . ."

"How much do you need?" the President repeated.

"I should judge about eight ounces."

"I see."

"That's only the amount required to test the concept fully," Donner added. "It would take an additional two hundred ounces to set up the equipment on a fully operational scale at strategic locations around the nation's borders."

The President slumped in his chair. "Then I guess we scrap this one and go on to something else."

Seagram was a tall lanky man, with a quiet voice and a courteous manner, and, except for a large, flattened nose, he could almost have passed as an unbearded Abe Lincoln.

Donner was just the opposite of Seagram. He was short and seemed almost as broad as he was tall. He had wheat colored hair, melancholy eyes, and his face always seemed to be sweating. He began talking at a machine-gun pace. "Project Sicilian is too close to reality to bury and forget. I strongly urge that we push on. We'd be playing for the inside straight to end inside straights, but if we succeed . . . my God, sir, the consequences are enormous."

"I'm open to suggestions," the President said quietly.

Seagram took a deep breath and plunged in. "First, we'd need your permission to build the necessary installations. Second, the required funds. And third, the assistance of the National Underwater and Marine Agency."

The President looked questioningly at Seagram. "I can understand the first two requests, but I don't grasp the significance of NUMA. Where does it fit in?"

"We're going to have to sneak expert mineralogists into Novaya Zemlya. Since it's surrounded by water, a NUMA oceanographic expedition nearby would make the perfect cover for our mission."

"How long will it take you to test, construct, and install the system?"

Donner didn't hesitate. "Sixteen months, one week."

"How far can you proceed without byzanium?"

"Right up to the final stage," Donner answered.

The President tilted back in his chair and gazed at a ship's clock that sat on his massive desk. He said nothing for nearly a full minute. Finally he said, "As I see it, gentlemen, you want me to bankroll you into building a multimillion dollar, unproven, untested, complex system that won't operate because we lack the primary ingredient which we may have to steal from an unfriendly nation."

Seagram fidgeted with his briefcase while Donner merely nodded.

"Suppose you tell me," the President continued, "how I explain a maze of these installations stretching around the country's perimeters to some tight-fisted liberal in Congress who gets it in his head to investigate?"

"That's the beauty of the system," said Seagram. "It's small and it's compact. The computers tell us that a building constructed along the lines of a small power station will do the job nicely. Neither the Russian spy satellites nor a farmer living next door will detect anything out of the ordinary."

The President rubbed his chin. "Why do you want to jump the gun on the Sicilian Project before you're one hundred-per-cent ready?"

"We're gambling, sir," said Donner. "We're gambling that in the next sixteen months we can either make a breakthrough and produce byzanium in the laboratory or find a deposit we can extract somewhere on earth."

"Even if it takes us ten years," Seagram blurted, "the installations would be in and waiting. Our only loss would be time."

The President stood up. "Gentlemen, I'll go along with your science-fiction scheme, but on one condition. You have exactly eighteen months and ten days. That's when the new man, whoever he may be, takes over my job. So if you want to keep your sugar daddy happy until then, get me some results."

The two men across the desk went limp.

At last Seagram managed to speak. "Thank you, Mr. President. Somehow, some way, the team will bring in the mother lode. You can count on it."

"Good. Now if you'll excuse me. I have to pose in the Rose Garden with a bunch of fat old Daughters of the American Revolution." He held out his hand. "Good luck, and remember, don't screw up your undercover operations. I don't want another Eisenhower U-2 spy mission to blow up in my face. Understood?"

Before Seagram and Donner could answer, he had turned and walked out a side door.

Donner's Chevrolet was passed through the White House gates. He eased into the mainstream of traffic and headed across the Potomac into Virginia. He was almost afraid to look in the rear view mirror for fear that the President might change his mind and send a messenger to chase them down with a rejection. He rolled down the window and breathed in the humid summer air.

"We came off lucky," Seagram said. "I guess you know that."

"You're telling me. If he'd known we'd sent a man into Russian territory over two weeks ago, the fertilizer would have hit the windmill."

"It still might," Seagram mumbled to himself. "It still might if NUMA can't get our man out."

2

Sid Koplin was sure he was dying.

His eyes were closed and the blood from his side was staining the white snow. A burst of light whirled around in Koplin's mind as consciousness gradually returned, and a spasm of nausea rushed over him and he retched uncontrollably. Had he been shot once, or was it twice? He wasn't sure.

He opened his eyes and rolled up onto his hands and knees. His head pounded like a jackhammer. He put his hand to it and touched a congealed gash that split his scalp above the left temple. Except for the headache, there was no exterior sensation; the pain had been dulled by the cold. But there was no dulling of the agonizing burn on his left side, just below his rib cage, where the second bullet had struck, and he could feel the syrup like stickiness of the blood as it trickled under his clothing, over his thighs and down his legs.

A volley of automatic weapons fire echoed down the mountain. Koplin looked around, but all he could see was the swirling white snow that was whipped by the vicious arctic wind. Another burst tore the frigid air. He guessed that it came from only a hundred yards away. A Soviet patrol guard must be firing blindly through the blizzard in the random hope of hitting him again.

All thought of escape had vanished now. It was finished. He knew he could never make it to the cove where he'd moored the sloop. Nor was he in any condition to sail the little twenty-eight-foot craft across fifty miles of open sea to a rendezvous with the waiting American oceanographic vessel.

He sank back in the snow. The bleeding had weakened him beyond further physical effort. The Russians must not find him. That was part of the bargain with Meta Section. If he must die, his body must not be discovered. Painfully, he began scraping snow over himself. Soon he would be only a small white mound on a desolate slope of Bednaya Mountain, buried forever under the constantly building ice sheet.

He stopped a moment and listened. The only sounds he heard were his own gasps and the wind. He listened harder, cupping his hands to his ears. Just audible through the howling wind he heard a dog bark.