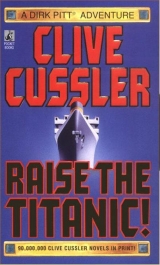

Текст книги "Raise the Titanic"

Автор книги: Clive Cussler

Соавторы: Clive Cussler

Жанр:

Морские приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

There was a morbid beauty about her. The men inside the submersible could almost see her dining saloons and staterooms flooded with lights and crowded with hundreds of light-hearted and laughing passengers. They could visualize her libraries stacked with books, her smoking rooms filled with the blue haze of gentlemen's cigars, and hear the music of her band playing turn-of-the-century ragtime. The passengers walked her decks, the wealthy, the famous, men in immaculate evening dress, women in colorful ankle-length gowns, nannies with children clutching favorite toys, the Astons, the Guggenheims, and the Strauses in first class; the middle-class, the school teachers, the clergymen, the students, and the writers in second; the immigrants, the Irish farmers and their families, the carpenters, the bakers, the dressmakers, and the miners from remote villages of Sweden, Russia, and Greece in steerage. Then there were the almost nine hundred crew members, from the ship's officers to the caterers, the stewards, the lift boys, and the engineroom men.

Great opulence lay in the darkness beyond the doors and portholes. What would the swimming pool, the squash court, and the Turkish baths look like? Was there a rotten remnant of the great tapestry still hanging in the reception room? What of the bronze clock on the grand staircase, or the crystal chandeliers in the elegant Cafe Parisien, or the delicately ornate ceiling above the first-class dining saloon? Would, perhaps, the bones of Captain Edward J. Smith remain somewhere within the shadows of the bridge? What mysteries were there to be discovered within this once colossal floating palace if and when she ever greeted the sun again?

The strobe light on the submersible's cameras seemed to flash endlessly as the tiny intruder circled the immense hulk. A large two-foot, rat-tailed fish with huge eyes and a heavy armored head skittered over the slanting decks, showing total unconcern for the exploding beams of light.

After what seemed like hours, the submersible, the faces of its crew still glued to the viewports, rose over the first-class lounge roof, hovered for a few moments, then deposited a small electronic-signal capsule. Its low frequency impulses would now provide a traceable guideline for future dives to the wreck. Then the submersible made a gliding turn upward, her lights blinked out, and she melted back into the darkness from whence she had come.

Except for the few sparks of marine life that had somehow managed to adapt to survival in the black, bitter-cold environment, the Titanic was alone once more. But soon other submersibles would come and she would feel the tools of man working on her steel skin again, as she had so many years ago at the great slipways of the Harland and Wolff shipbuilding firm in Belfast.

Then, just perhaps, she would make her first port after all.

THE TITANIC

May 1988

37

In a measured and precise manner, the Soviet General Secretary, Georgi Antonov lit his pipe and surveyed the other men seated around the long mahogany conference table.

To his right sat Admiral Boris Sloyuk, director of Soviet Naval Intelligence, and his aide, Captain Prevlov. Opposite them were Vladimir Polevoi, Chief of the Foreign Secrets Department of the KGB, and Vasily Tilevitch, Marshal of the Soviet Union and chief director of Soviet Security.

Antonov came straight to the point "Well now, it seems the Americans are determined to raise the Titanic to the surface." He studied the papers sitting before him a few moments before continuing. "An extensive effort by the look of it. Two supply ships, three tenders, four deep-sea submersibles." He looked up at Admiral Sloyuk and Prevlov. "Do we have an observer in the area?"

Prevlov nodded. "The oceanographic research vessel Mikhail Kurkov, under the command of Captain Ivan Parotkin, is cruising the salvage perimeter."

"I know Parotkin personally," Sloyuk added. "He is a good seaman."

"If the Americans are spending hundreds of millions of dollars in an attempt to salvage a seventy-six-year-old piece of scrap," Antonov said, "there must be a logical motivation."

"There is a motivation," Admiral Sloyuk said gravely. "A motivation that threatens our very security." He nodded to Prevlov, who began passing out a red folder marked "Sicilian Project" to Antonov and the men across the table. "That is why I requested this meeting. My people have discovered outline plans for a new secret American defense system. I think you will find it a shocking, if not terrifying, study."

Antonov and the others opened the folders and began reading. For perhaps five minutes, the Soviet General Secretary read, occasionally glancing in Sloyuk's direction. Antonov's face went through a wide range of expressions, beginning with professional interest to frank bewilderment, to astonishment, and, finally, stunned realization.

"This, is incredible, Admiral Sloyuk, absolutely incredible."

"Is such a defense system possible?" Marshal Tilevitch asked.

"I have put the same question to five of our most respected scientists. They all agreed, theoretically, that such a system is feasible, provided a strong enough power source is available."

"And you assume this source lies in the cargo holds of the Titanic?" Tilevitch put to him.

"We are certain of it, Comrade Marshal. As I mentioned in the report, the vital ingredient needed for the completion of the Sicilian Project is a little-known element called byzanium. We now know the Americans stole the world's only supply from Russian soil seventy-six years ago. Fortunately for us, they had the ill luck to transport it on a doomed ship."

Antonov shook his head in utter incomprehension. "If what you say in your report is true, then the Americans have the potential to knock down our intercontinental missiles as effortlessly as a goatherd swats flies.''

Sloyuk nodded solemnly. "I am afraid that is the fearful truth."

Polevoi leaned across the table, his face a mask of suspicious consternation. "You state here that your contact is a high-level aide in the United States Department of Defense."

"That is correct." Prevlov nodded respectfully. "He became disillusioned with the American government during the Watergate affair and has since sent me whatever material he deems important."

Antonov stared piercingly into Prevlov's eyes. "Do you think they can do it, Captain Prevlov?"

"Raise the Titanic?"

Antonov nodded.

Prevlov stared back. "If you will recall the Central Intelligence Agency's successful recovery of one of our Soviet nuclear submarines in seventeen thousand feet of water off Hawaii in 1974-I believe the CIA referred to it as Project Jennifer-there is little doubt that the Americans have the technical capability to put the Titanic in New York harbor. Yes, Comrade Antonov, I firmly believe they will do it.

"I do not share your opinion," said Polevoi. "A vessel the size of the Titanic is a far cry from a submarine."

"I have to throw in my lot with Captain Prevlov," Sloyuk argued. "The Americans have an annoying habit of accomplishing what they set out to do."

"And what of this Sicilian Project?" Polevoi persisted. "The KGB has received no detailed data concerning its existence except the code name. How do we know the Americans have not created a mythical project to play a bluffing hand at the negotiations to limit strategic nuclear delivery systems?"

Antonov rapped his knuckles on the tabletop. "The Americans do not bluff. Comrade Khrushchev found that out twenty-five years ago during the Cuban missile crisis. We cannot ignore any possibility, however remote, that they are on the verge of making this defense system operational as soon as they salvage the byzanium from the hull of the Titanic. "He paused to suck on his pipe stem. "I suggest that our next thoughts be directed toward a course of action."

"Quite obviously we must see to it that the byzanium never reaches the United States," Marshal Tilevitch said.

Polevoi drummed his fingers on the Sicilian Project file. "Sabotage. We must sabotage the salvage operation. There is no other way."

"There must be no incident with international repercussions," Antonov said firmly. "There can be no suggestion of interference through overt military action. I do not want Soviet-United States relations jeopardized during yet another bad crop year. Is that clear?"

"We can do nothing unless we penetrate the salvage area," Tilevitch persisted.

Polevoi stared across the table at Sloyuk. "What steps have the Americans taken to protect the operation?"

"The nuclear-powered guided-missile cruiser Juneau is patrolling within sight of the salvage ships on a twenty-four-hour basis."

"May I speak?" Prevlov asked almost condescendingly. He did not wait for an answer. "With due consideration, comrades, the penetration has already taken place"

Antonov looked up. "Please explain yourself, Captain."

Prevlov took a side glance at his superior. Admiral Sloyuk acknowledged him with a faint nod.

"We have two undercover operatives working as members of the NUMA salvage crew," Prevlov elucidated. "An exceptionally talented team. They have been relaying important American oceanographic data to us for two years."

"Good, good. Your people have done well, Sloyuk," Antonov said, but there was no warmth in his tone. His gaze came back to Prevlov. "Are we to assume, Captain, that you have devised a plan?"

"I have, comrade."

Marganin was in Prevlov's office when he returned, casually sitting behind the captain's desk. There was a change about him. No longer did he seem like the common, bootlicking aide that Prevlov had left only a few hours ago. There was something about him that was more certain, more self-assured. It seemed to be in his eyes. Those insecure eyes now mirrored the confident look of a man who knew what he was about.

"How did the conference go, Captain?" Marganin asked without rising.

"I think I can safely say the day will soon come when you will be addressing me as Admiral."

"I must confess," Marganin said coolly, "your fertile mind is surpassed only by your ego."

Prevlov was caught off guard. His face paled with controlled anger, and, when he spoke, it required no acute sense of hearing or imagination to detect the emotion in his voice. "You dare to insult me?"

"Why not. You undoubtedly sold Comrade Antonov on the fact that it was your genius that arrived at the purpose of the Sicilian Project and the Titanic salvage operation, when, in reality, it was my source who passed along the information. And you also most likely told them about your wonderful plan to wrest the byzanium from the Americans' hands. Again, stolen from me. In short, Prevlov, you are nothing but an untalented thief."

"That will do!" Prevlov was pointing a finger at Marganin, his tone glacial. Suddenly, he stiffened and was completely under control again, intent, urbane, the true professional. "You will burn for your insubordination, Marganin," he said pleasantly. "I will see to it that you burn a thousand deaths before this month is through."

Marganin said nothing. He only smiled a smile that was as cold as a tomb.

38

"So much for secrecy," Seagram said, dropping a newspaper on Sandecker's desk. "That's this morning's paper. I picked it up from a newsstand not fifteen minutes ago."

Sandecker turned it around and looked at the front page. He didn't have to look farther, it was all there.

"`NUMA To Raise Titanic, "' he read aloud. "Well, at least we don't have to pussyfoot around any more. 'Multimillion dollar effort to salvage ill-fated liner.' You have to admit, it makes for fascinating reading. `Informed sources said today that the National Underwater and Marine Agency is conducting an all-out salvage attempt to raise the R.M.S.Titanic, which struck an iceberg and sank in the mid-Atlantic on April 15, 1912, with a loss of over fifteen hundred lives. This tremendous undertaking heralds a new dawn in deep-sea salvage that is without parallel in the history of man's search for treasure."'

"A multimillion-dollar treasure hunt," Seagram frowned darkly. "The President will love that."

"Even has a picture of me," Sandecker said. "Not a good likeness. Must be a stock photo from their files, taken maybe five or six years ago."

"It couldn't have come at a worse time," Seagram said. "Three more weeks . . . Pitt said he would try to lift her in three more weeks."

"Don't hold your breath. Pitt and his crew have been at it for nine months; nine grueling months of battling every winter storm the Atlantic could throw at them, tackling every setback and technical adversity as it came up. It's a miracle they've accomplished so much in so little time. And yet, a thousand and one things can still go wrong. There may be hidden structural cracks that might split the hull wide open when it breaks from the sea floor, or then again, the enormous suction between the keel and the bottom ooze might never release its grip. If I were you, Seagram, I wouldn't get a glow on until you see the Titanic being towed past the Statue of Liberty."

Seagram looked wounded. The admiral grinned at his stricken expression and offered him a cigar. It was refused.

"On the other hand," Sandecker said comfortingly, "she may rise to the surface as pretty as you please."

"That's what I like about you, Admiral, your on-again, off-again optimism."

"I like to prepare myself for disappointments. It helps to ease the pain."

Seagram didn't reply. He was silent for a minute. Then he said, "So we worry about the Titanic when the time comes. But we still have the problem of the press to consider. How do we handle it?"

"Simple," Sandecker said airily. "We do what any redblooded, grass-roots politician would do when his shady record is laid bare by scandal-hungry reporters."

"And that is?" Seagram asked warily.

"We call a press conference."

"That's madness. If Congress and the public ever got wind of the fact that we've poured over three-quarters of a billion dollars into this thing, they'll be on us like a Kansas tornado."

"So we play liar's poker and slice the salvage costs in half for publication. Who's to know? There's no way the true figure can be uncovered."

"I still don't like it," Seagram said. "These Washington reporters are master surgeons when it comes to dissecting a speaker at a press conference. They'll carve you up like a Thanksgiving turkey."

"I wasn't thinking of me," Sandecker said slowly.

"Then who? Certainly not me. I'm the little man who isn't here, remember?"

"I had someone else in mind. Someone who is ignorant of our behind-the-scenes skullduggery. Someone who is an authority on sunken ships and whom the press would treat with the utmost courtesy and respect."

"And where are you going to find this paragon of virtue?"

"I'm awfully glad you used the word virtue," Sandecker said slyly. "You see, I was thinking of your wife."

39

Dana Seagram stood confidently at the lectern and deftly fielded the questions put to her by the eighty-odd reporters seated in the NUMA headquarters auditorium. She smiled continuously, with the happy look of a woman who is enjoying herself and who knows she would be approved of. She wore a terra-cotta color wrap skirt and a deeply V'd sweater, neatly accented by a small mahogany necklace. She was tall, appealing, and elegant; an image that immediately put her inquisitors at a disadvantage.

A white-haired woman on the left side of the room rose and waved her hand. "Dr. Seagram?"

Dana nodded gracefully.

"Dr. Seagram, the readers of my paper, the Chicago Daily, would like to know why the government is spending millions to salvage an old rusty ship. Why wouldn't the money be better spent elsewhere, say for welfare or badly needed urban renewal?"

"I'll be happy to clear the air for you," Dana said. "To begin with, raising the Titanic is not a waste of money. Two hundred and ninety million dollars have been budgeted, and so far we are well below that figure; and, I might add, ahead of schedule."

"Don't you consider that a lot of money?"

"Not when you consider the possible return. You see, the Titanic is a veritable storehouse of treasure. Estimates run over three hundred million dollars. There are many of the passengers' jewels and valuables still on board a quarter of a million dollars' worth in one stateroom alone. Then there are the ship's fittings, as well as the furnishings and the precious decor, some of which may have survived. A collector would gladly pay anywhere from five hundred to a thousand dollars for one piece of china or a crystal goblet from the first-class dining room. No, ladies and gentlemen, this is one time when a federal project is not, if you'll pardon the expression, a taxpayer ripoff. We will show a profit in dollars and a profit in historical artifacts of a bygone era, not to mention the tremendous wealth of data for marine science and technology."

"Dr. Seagram?" This from a tall, pinch-faced man in the rear of the auditorium. "We haven't had time to read the press release you passed out earlier, so could you please enlighten us as to the mechanics of the salvage?"

"I'm glad you asked me that." Dana laughed. "Seriously, I apologize for the old cliche, but your question, sir, is the cue for a brief slide presentation that should help explain many of the mysteries regarding the project." She turned to the wings of the stage. "Lights, please."

The lighting dimmed and the first slide marched onto a wide screen above and behind the lectern.

"We begin with a composite of over eighty photographs pieced together to show the Titanic as she rests on the sea floor. Fortunately, she's sitting upright with a light list to port which conveniently puts the hundred-yard-long gash she received from the iceberg in an accessible position to seal."

"How is it possible to seal an opening that size at that enormous depth?"

The next slide came on and showed a man holding what looked like a large blob of liquid plastic.

"In answer to that question," Dana said, "this is Dr. Amos Stannford demonstrating a substance he developed called `Wetsteel.' As the name suggests, Wetsteel, though pliable in air, hardens to the rigidity of steel ninety seconds after coming in contact with water, and it can bond itself to a metal object as though it were welded."

This last statement was followed by a wave of murmurs throughout the room.

"Ball-shaped aluminum tanks, ten feet in diameter, that contain Wetsteel have been dropped at strategic spots around the vessel," Dana continued. "They are designed so that a submersible can attach itself to the tank, not unlike the docking procedure of a shuttle rocket with a space laboratory, and then proceed to the working area where the crew can aim and expel the Wetsteel from a specially designed nozzle."

"How is the Wetsteel pumped from the tank?"

"To illustrate with another comparison, the great pressure at that depth compresses the aluminum tank much like a tube of toothpaste, squeezing the sealant through the nozzle and into the opening to be covered."

She signaled for a new slide.

"Now here we see a cut-away drawing of the sea, depicting the supply tenders on the surface and the submersibles clustered around the wreck on the bottom. There are four manned underwater vehicles involved in the salvage operation. The Sappho I, which you may recall was the craft used on the Lorelei Current Drift Expedition, is currently engaged in patching the damage caused by the iceberg along the starboard side of the hull and also the bow, where it was shattered by the Titanic's boilers. The Sappho II, a newer and more advanced sister ship, is sealing the smaller openings, such as the air vents and portholes. The Navy's submersible, the Sea Slug, has the job of cutting away unnecessary debris, including the masts, rigging, and the aft funnel which fell across the After Boat Deck. And finally, the Deep Fathom, a submersible belonging to the Uranus Oil Corporation, is installing pressure relief valves on the Titanic's hull and superstructure."

"Could you please explain the purpose of the valves, Dr. Seagram?"

"Certainly," Dana replied. "When the hulk begins its journey to the surface, the air that has been pumped into her interior will begin to expand as the pressure of the sea lessens against her exterior. Unless this inside pressure is continuously bled, the Titanic could conceivably blow herself to pieces. The valves, of course, are there to prevent this disastrous occurrence."

"Then NUMA intends to use compressed air to lift the derelict?"

"Yes, the support tender, Capricorn, has two compressor units capable of displacing the water in the Titanic's hull with enough air to raise her."

"Dr. Seagram?" came another disembodied voice, "I represent Science Today, and I happen to know that the water pressure where the Titanic lies is upwards of six thousand pounds per square inch. I also know that the largest available air compressor can only put out four thousand pounds. How do you intend to overcome this differential?"

"The main unit on board the Capricorn pumps the air from the surface through a reinforced pipe to the secondary pump, which is stationed amidships of the wreck. In appearance, this secondary pump looks like a radial aircraft engine with a series of pistons spreading from a central hub. Again, we utilized the sea's great abyssal pressures to activate the pump, which is also assisted by electricity and the air pressure coming from above. I am sorry I can't give you an in-depth description, but I am a marine archaeologist, not a marine engineer. However, Admiral Sandecker will be available later in the day to answer your technical questions in greater detail."

"What about suction?" the voice of Science Today persisted. "After sitting imbedded in the silt all these years, won't the Titanic be fairly well glued to the bottom?"

"She will indeed." Dana gestured for the lights. They came on and she stood blinking in the glare for a few moments until she could distinguish her inquirer. He was a middle-aged man, with long brown hair and large wire rimmed glasses.

"When it is calculated that the ship has enough air to lift her mass toward the surface, the air pipe will be disconnected from the hull and converted to inject an electrolyte chemical, processed by the Myers-Lentz Company, into the sediment surrounding the Titanic's keel. The resulting reaction will cause the molecules in the sediment to break down and form a cushion of bubbles that will erase the static friction and allow the great hulk to wrest herself free from the suction."

Another man raised his hand.

"If the operation is successful and the Titanic begins floating toward the surface, isn't there a good chance she could capsize? Two and a half miles is a long way for an unbalanced object of forty-five thousand tons to remain upright."

"You're right. There is the possibility she might capsize, but we plan to leave enough water in her lower holds to act as ballast and offset this problem."

A young, mannish-looking woman rose and waved her hand.

"Dr. Seagram! I am Connie Sanchez of Female Eminence Weekly, and my readers would be interested in learning what defense mechanisms you have personally developed for competing on a day-to-day basis in a profession dominated by egotistic male pigheads."

The audience of reporters greeted the question with uneasy silence. God, Dana thought to herself, it had to come sooner or later. She stepped alongside the lectern and leaned on it in a negligent, almost sexy attitude.

"My reply, Ms. Sanchez, is strictly off the record."

"Then you're copping out," said Connie Sanchez with a superior grin.

Dana ignored the jab. "First, I find that a defense mechanism is hardly necessary. My masculine colleagues respect my intelligence enough to accept my opinions. I don't have to go bra-less or spread my legs to get their attention. Second, I prefer standing on my own home ground and competing with members of my own sex, not a strange stance when you consider the fact that out of five hundred and forty scientists on the staff of NUMA, a hundred and fourteen are women. And third, Ms. Sanchez, the only pigheads it's been my misfortune to meet during my life have not been men, but rather the female of the species."

For several moments, a stunned silence gripped the room. Then, suddenly, shattering the embarrassed quiet, a voice burst from the audience. "Atta girl, Doc," yelled the little white-haired lady from the Chicago Daily. "That's putting her down."

A sea of applause rippled and then roared, sweeping the auditorium in a storm of approval. The battle-hardened Washington correspondents offered her their respect with a standing ovation.

Connie Sanchez sat in her seat and stared coldly in flushed anger. Dana saw Connie's lips form the word "bitch" and she returned a smug, derisive kind of smile that only women do so well. Adulation, Dana thought, how sweet it is.

40

Since early morning the wind had blown steadily out of the northeast. By later afternoon it had increased to a gale of thirty-five knots, which in turn threw up mountainous seas that pitched the salvage ships about like paper cups in a dishwasher. The tempest carried with it a numbing cold borne of the barren wastes above the Arctic Circle. The men dared not venture out onto the icy decks. It was no secret that the greatest barrier against keeping warm was the wind. A man could feel much colder and more miserable at twenty degrees above zero Fahrenheit with a thirty-five-knot wind than at twenty degrees below zero with no wind. The wind steals the body heat as quickly as it can be manufactured-a nasty situation known as chill factor.

Joel Farquar, the Capricorn's weatherman, on loan from the Federal Meteorological Services Administration, seemed unconcerned with the storm snapping outside the operations room as he studied the instrumentation that tied into the National Weather Satellites and provided four space pictures of the North Atlantic every twenty-four hours.

"What does your prognosticating little mind see for our future?" Pitt asked, bracing his body against the roll.

"She'll start easing in another hour," Farquar replied "By sunrise tomorrow the wind should be down to ten knots."

Farquar didn't look up when he spoke. He was a studious, little red-faced man with utterly no sense of humor and no trace of friendly warmth. Yet, he was respected by every man on the salvage operation because of his total dedication to the job, and the fact that his predictions were uncannily accurate.

"The best laid plans . . ." Pitt murmured idly to himself. "Another day lost. That's four times in one week we've had to cast off and buoy the air line."

God can make a storm," Farquar said indifferently. He nodded toward the two banks of television monitors that covered the forward bulkhead of the Capricorn's operations room. "At least they're not bothered by it all."

Pitt looked at the screens which showed the submersibles calmly working on the wreck twelve thousand feet below the relentless sea. Their independence from the surface was the saving grace of the project. With the exception of the Sea Slug, which only had a downtime of eighteen hours and was now securely tied on the Modoc's deck, the other three submersibles could be scheduled to stay down on the Titanic for five days at a stretch before they returned to the surface to change crews. He turned to Al Giordino, who was bent over a large chart table.

"What's the disposition of the surface ships?"

Giordino pointed at the tiny two-inch models scattered about the chart. "The Capricorn is holding her usual position in the center. The Modoc is dead ahead, and the Bomberger is trailing three miles astern."

Pitt stared at the model of the Bomberger. She was a new vessel, constructed especially for deep-water salvage. "Tell her captain to close up to within one mile."

Giordino nodded toward the bald radio operator, who was moored securely to the slanting deck in front of his equipment. "You heard the man, Curly. Tell the Bomberger to come up to one mile astern."

"How about the supply ships?" Pitt asked.

"No problem there. This weather is duck soup to big ten-tonners the likes of these two. The Alhambra is in position to port, and the Monterey Park is right where she's supposed to be to starboard."

Pitt nodded at a small red model. "I see our Russian friends are still with us."

"The Mikhail Kurkov?" Giordino said. He picked up a blue replica of a warship and placed it next to the red model. "Yeah, but she can't be enjoying the game. The Juneau, that Navy guided-missile cruiser, hangs on like glue."

"And the wreck buoy's signal unit?"

"Serenely beeping away eighty feet beneath the uproar," Giordino announced. "Only twelve hundred yards, give or take a hair, bearing zero-five-nine, southwest that is."

"Thank God we haven't been blown off the homestead," Pitt sighed.

"Relax." Giordino grinned reassuringly. "You act like a mother with a daughter out on a date after midnight every time there's a little breeze."

"The mother-hen complex becomes worse the closer we get," Pitt admitted. "Ten more days, Al. If we can get ten calm days, we can wrap it up."

"That's up to the weather oracle." Giordino turned to Farquar. "What about it, O Great Seer of Meteorological Wisdom?"

"Twelve hours' advance notice is all you'll get out of me," Farquar grunted, without looking up. "This is the North Atlantic. She's the most unpredictable of any ocean in the world. Hardly one day is ever the same. Now, if your precious Titanic had gone down in the Indian Ocean, I could give you your ten day prediction with an eighty percent chance of accuracy."