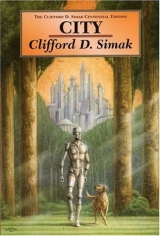

Текст книги "City"

Автор книги: Clifford D. Simak

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

And what they played, thought Jenkins, became a bitter fact. A fact for almost a thousand years. A fact until we found them and brought them home again. Back to the Webster House, back to where the whole thing started.

***

Jenkins folded his hands in his lap and bent his head and rocked slowly to and fro. The rocker creaked and the wind raced in the eaves and a window rattled. The fireplace talked with its sooty throat, talked of other days and other folks, of other winds that blew from out the west.

The past, thought Jenkins. It is a footless thing. A foolish thing when there is so much to do. So many problems that the Dogs have yet to meet. Over-population, for example. That's the thing we've thought about and talked about too long. Too many rabbits because no wolf or fox may kill them. Too many deer because the mountain lions and the wolves must eat no venison. Too many skunks, too many mice, too many wildcats. Too many squirrels, too many porcupines, too many bear.

Forbid the one great check of killing and you have too many lives. Control disease and succour injury with quick-moving robot medical technicians and another check is gone.

Man took care of that, said Jenkins. Yes, men took care of that. Men killed anything that stood within their path – other men as well as animals.

Man never thought of one great animal society, never dreamed of skunk and coon and bear going down the road of life together, planning with one another, helping one another – setting aside all natural differences.

But the Dogs had. And the Dogs had done it.

Like a Brother Rabbit story, thought Jenkins. Like the childhood fantasy of a long gone age. Like the story in the Good Book about the Lion and the Lamb lying down together. Like a Walt Disney cartoon except that the cartoon never had rung true, for it was based on the philosophy of mankind.

***

The door creaked open and feet were on the floor. Jenkins shifted in his chair.

"Hello, Joshua," he said. "Hello, Ichabod. Won't you please come in? I was just sitting here and thinking."

"We were passing by," said Joshua, "and we saw a light."

"I was thinking about the lights," said Jenkins, nodding soberly. "I was thinking about the night five thousand years ago. Jon Webster had come out from Geneva, the first man to come here for many hundred years. And he was upstairs in bed and all the Dogs were sleeping and I stood there by the window looking out across the river. And there were no lights. No lights at all. Just one great sweep of darkness. And I stood there, remembering the day when there had been lights and wondering if there ever would be lights again."

"There are lights now," said Joshua, speaking very softly. "There are lights all over the world to-night. Even in the caves and dens."

"Yes, I know," said Jenkins. "It's even better than it was before."

Ichabod clumped across the floor to the shining robot body standing in the corner, reached out one hand and stroked the metal hide, almost tenderly.

"It was very nice of the Dogs," said Jenkins, "to give me the body. But they shouldn't have. With a little patching here and there, the old one's good enough."

"It was because we love you," Joshua told him. "It was the smallest thing the Dogs could do. We have tried to do other things for you, but you'd never let them do them. We wish that you would let us build you a new house, brand new, with all the latest things."

Jenkins shook his head. "It wouldn't be any use, because I couldn't live there. You see, this place is home. It has always been my home. Keep it patched up like my body and I'll be happy in it."

"But you're all alone."

"No, I'm not," said Jenkins. "The house is simply crowded."

"Crowded?" asked Joshua.

"People that I used to know," said Jenkins.

"Gosh," said Ichabod. "what a body! I wish I could try it on."

"Ichabod!" yelled Joshua. "You come back here. Keep your hands off that body-"

"Let the youngster go," said Jenkins. "If he comes over here some time when I'm not busy-"

"No," said Joshua.

A branch scraped against the cave and tapped with tiny fingers along the windowpane. A shingle rattled and the wind marched across the roof with tripping, dancing feet.

"I'm glad you stopped by," said Jenkins. "I want to talk to you."

He rocked back and forth and one of the rockers creaked. "I won't last forever," Jenkins said. "Seven thousand years is longer than I had a right to expect to hang together."

"With the new body," said Joshua, "you'll be good for three times seven thousand more."

Jenkins shook his head. "It's not the body I'm thinking of. It's the brain. It's mechanical, you see. It was made well, made to last a long time, but not to last forever. Sometime something will go wrong and the brain will quit."

The rocker creaked in the silent room.

"That will be death," said Jenkins. "That will be the end of me.

"And that's all right. That's the way it should be. For I'm no longer any use. Once there was a time when I was needed."

"We will always need you," Joshua said softly. "We couldn't get along without you."

But Jenkins went on, as if he had not heard him. "I want to tell you about the Websters. I want to talk about them. I want you to understand."

"I will try to understand," said Joshua.

'You Dogs call them websters and that's all right," said Jenkins. "It doesn't matter what you call them, just so you know what they are."

"Sometimes," said Joshua, "you call them men and sometimes you call them websters. I don't understand."

"They were men," said Jenkins, "and they ruled the earth. There was one family of them that went by the name of Webster. And they were the ones who did this great thing for you."

"What great thing?"

Jenkins hitched the chair around and held it steady. "I am forgetful," he mumbled. "I forget so easily. And I get mixed up."

"You were talking about a great thing the websters did for us."

"Eh," said Jenkins. "Oh, so I was. So I was. You must watch them. You must caare for them and watch them. Especially you must watch them."

He rocked slowly to and fro and thoughts ran in his brain, thoughts spaced off by the squeaking of the rocker.

You almost did it then, he told himself. You almost spoiled the dream.

But I remembered in time. Yes. Jon Webster, I caught myself in time. I kept faith, Jon Webster.

I did not tell Joshua that the Dogs once were pets of men, that men raised them to the place they hold today. For they must never know. They must hold up their heads. They must carry on their work. The old fireside tales are gone and they must stay gone forever.

Although I'd like to tell them, Lord knows, I'd like to tell them. Warn them against the thing they must guard against. Tell them how we rooted out the old ideas from the cavemen we brought back from Europe. How we untaught them the many things they knew. How we left their minds blank of weapons, how we taught them love and peace.

And how we must watch against the day when they'll pick up those trends again – the old human way of thought.

***

"But you said..." persisted Joshua.

Jenkins waved his hand. "It was nothing, Joshua. Just an old robot's mumbling. At times my brain gets fuzzy and I say things that I don't mean. I think so much about the past – and you say there isn't any past."

Ichabod squatted on his haunches on the floor and looked up at Jenkins.

"There sure ain't none," he said. "We checked her, forty ways from Sunday, and all the factors, check. They all add up. There isn't any past."

"There isn't any room," said Joshua. "You travel back along the line of time and you don't find the past, but another world, another bracket of consciousness. The earth would be the same, you see, or almost the same. Same trees, same rivers, same hills, but it wouldn't be the world we know. Because it has lived a different life, it has developed differently. The second back of us is not the second back of us at all, but another second, a totally separate sector of time. We live in the same second all the time. We move along within the bracket of that second, that tiny bit of time that has been allotted to our particular world."

"The way we keep time was to blame," said Ichabod. "It was the thing that kept us from thinking of it in the way it really was. For we thought all the time that we were passing through time when we really weren't, when we never have. We've just been moving along with time. We said, there's another second gone, there's another minute and another hour and another day, when, as a matter of fact the second or the minute or the hour was never gone. It was the same one all the time. It had just moved along and we had moved with it."

Jenkins nodded. "I see. Like driftwood on the river. Chips moving with the river. And the scene changes along the river bank, but the water is the same."

"That's roughly it," said Joshua. "Except that time is a rigid stream and the different worlds are more firmly fixed in place than the driftwood on the river."

"And the cobblies live in those other worlds?"

Joshua nodded. "I'm sure they must."

"And now," said Jenkins, "I suppose you are figuring out a way to travel to those other worlds."

Joshua scratched softly at a flea.

"Sure he is," said Ichabod. "We need the space."

"But the cobblies-"

"The cobblies might not be on all the worlds," said Joshua. "There might be some empty worlds. If we can find them, we need those empty worlds. If we don't find space, we are up against it. Population pressure will bring on a wave of killing. And a wave of killing will set us back to where we started out."

"There's already killing," Jenkins told him quietly.

Joshua wrinkled, his brow and laid back his ears. "Funny killing. Dead, but not eaten. No blood. As if they just fell over. It has our medical technicians half crazy. Nothing wrong. No reason that they should have died."

"But they did," said Ichabod.

Joshua hunched himself closer, lowered his voice. I'm afraid, Jenkins. I'm afraid that-"

"There's nothing to be afraid of."

"But there is. Angus told me. Angus is afraid that one of the cobblies... that one of the cobblies got through."

***

A gust of wind sucked at the fireplace throat and gamboled in the eaves. Another gust hooted in some near, dark corner. And fear came out and marched across the roof, marched with thumping, deadened footsteps up and down the shingles.

Jenkins shivered and held himself tight and rigid against another shiver. His voice grated when he spoke.

"No one has seen a cobbly."

"You might not see a cobbly."

"No," said Jenkins. "No. You might not see one."

And that is what Man had said before. You did not see a ghost and you did not see a haunt – but you sensed that one was there. For the water tap kept dripping when you had shut it tight and there were fingers scratching at the pane and the dogs would howl at something in the night and there'd be no tracks in the snow.

And there were fingers scratching on the pane.

***

Joshua came to his feet and stiffened, a statue of a dog, one paw lifted, lips curled back in the beinning of a snarl. Ichabod crouched, toes dug into the floor – listening, waiting.

The scratching came again.

"Open the door," Jenkins said to Ichabod. "There is something out there wanting to get in."

Ichabod moved through the hushed silence of the room. The door creaked beneath his hand. As he opened it, the squirrel came bounding in, a grey streak that leaped for Jenkins and landed in his lap.

"Why, Fatso," Jenkins said.

Joshua sat down again and his lips uncurled, slid down to hide his fangs, Ichabod wore a silly metal grin.

"I saw him do it," screamed Fatso. "I saw him kill the robin. He did it with a throwing stick. And the feathers flew. And there was blood upon the leaf."

"Quiet," said Jenkins gently. "Take your time and tell me. You are too excited. You saw someone kill a robin."

Fatso sucked in a breath and his teeth were chattering.

"It was Peter," be said. "Peter?"

"Peter, the webster."

"You said he threw a stick?"

"He threw it with another stick. He had the two ends tied together with a cord and he pulled on the cord and the stick bent-"

"I know," said Jenkins. "I know."

"You know! You know all about it?"

"Yes," said Jenkins, "I know all about it. It was a bow and arrow."

And there was something in the way he said it that held the other three to silence, making the room seem big and empty and the tapping of the branch against the pane a sound from far away, a hollow, ticking voice that kept on complaining without the hope of aid.

"A bow and arrow?" Joshua finally asked. "What is a bow and arrow?"

And what was it, thought Jenkins.

What is a bow and arrow?

It is the beginning of the end. It is the winding path that grows to the roaring road of war.

It is a plaything and a weapon and a triumph in human engineering.

It is the first faint stirring of an atom bomb.

It is a symbol of a way of life.

And it's a line in a nursery rhyme. Who killed Cock Robin.

I, said the sparrow. With my bow and arrow, I killed Cock Robin.

And it was a thing forgotten. And a thing relearned. It is the thing that I've been afraid of.

He straightened in his chair, came slowly to his feet. "Ichabod," he said, "I will need your help." "Sure," said Ichabod. "Anything you like." "The body," said Jenkins. "I want to wear my new body. You'll have to unseat my brain case-"

Ichabod nodded. "I know how to do it, Jenkins." Joshua's voice had a sudden edge of fear. "What is it, Jenkins? What are you going to do?"

"I'm going to the Mutants," Jenkins said, speaking very slowly. "After all these years, I'm going to ask their help."

***

The shadow slithered down the hill, skirting the places where the moonlight flooded through forest openings. He glimmered in the moonlight – and he must not be seen. He must not spoil the hunting of the others that came after.

There would be others. Not in a flood, of course, but carefully controlled. A few at a time and well spread out so that the life of this wondrous world would not take alarm.

Once it did take alarm, the end would be in sight. The shadow crouched in the darkness, low against the ground, and tested the night with twitching, high-strung nerves. He separated out the impulses that he knew, cataloguing them in his knife-sharp brain, filing them neatly away as a check against his knowledge.

And some he knew and some were mystery, and others he would guess at. But there was one that held a hint of horror.

He pressed himself close against the ground and held his ugly head out straight and flat and closed his perceptions against the throbbing of the night, concentrating on the thing that was coming up the hill.

There were two of them and the two were different. A snarl rose in his mind and bubbled in his throat and his tenuous body tensed into something that was half slavering expectancy and half cringing outland terror.

He rose from the ground, still crouched, and flowed down the hill, angling to cut the path of the two who were coming up.

***

Jenkins was young again, young and strong and swift – swift of brain and body. Swift to stride along the wind-swept, moon-drenched hills. Swift to hear the talking of the leaves and the sleepy chirp of birds – and more than that.

Yes, much more than that, he admitted to himself. The body was a lulu. A sledge hammer couldn't dent it and it would never rust. But that wasn't all.

Never figured a body's make this much difference to me. Never knew how ramshackle and worn out the old one really was. A poor job from the first, although it was the best that could be done in the days when it was made. Machinery sure is wonderful, the tricks they can make it do.

It was the robots, of course. The wild robots. The Dogs had fixed it up with them to make the body. Not very often the Dogs had much truck with the robots. Got along all right and all of that – but they got along because they let one another be, because they didn't interfere, because neither one was nosey.

There was a rabbit stirring in his den – and Jenkins knew it. A raccoon was out on a midnight prowl and Jenkins knew that, too – knew the cunning, sleek curiosity that went on within the brain behind the little eyes that stared at him from the dump of hazel brush. And off to the left, curled up beneath a tree, a bear was sleeping and dreaming as he slept – a glutton's dream of wild honey and fish scooped out of a creek, with ants licked from the underside of an upturned rock as relish for the feast.

And it was startling – but natural. As natural as lifting one's feet to walk, as natural as normal hearing was. But it wasn't hearing and it wasn't seeing. Nor yet imagining. For Jenkins knew with a cool, sure certainty about the rabbit in the den and the coon in the hazel brush and the bear who dreamed in his sleep beneath the tree.

And this, he thought, is the kind of bodies the wild robots have – for certainly if they could make one for me, they'd make them for themselves.

They have come a long ways, too, in seven thousand years, even as the Dogs have travelled far since the exodus of humans. But we paid no attention to them, for that was the way it had to be. The robots went their way and the Dogs went theirs and they did not question what one another did, had no curiosity about what one another did. While the robots were building spaceships and shooting for the stars, while they built bodies, while they worked with mathematics and mechanics, the Dogs had worked with animals, had forged a brotherhood of the things that had been wild and hunted in the days of Man – had listened to the cobblies and tried to probe the depths of time to find there was no time.

And certainly if the Dogs and robots have gone as far as this, the Mutants had gone farther still. And they will listen to me, Jenkins said, they will have to listen, for I'm bringing them a problem that falls right into their laps. Because the Mutants are men – despite their ways, they are the sons of Man. They can bear no rancour now, for the name of Man is a dust that is blowing with the wind, the sound of leaves on a summer day, and nothing more.

Besides, I haven't bothered them for seven thousand years – not that I ever bothered them. Joe was a friend of mine, or as close to a friend as a Mutant ever had. He'd talk with me when he wouldn't talk with men. They will listen to me – they will tell me what to do. And they will not laugh.

Because it's not a laughing matter. It's just a bow and arrow, but it's not a laughing matter. It might have been at one time, but history takes the laugh out of many things. If the arrow is a joke, so is the atom bomb, so is the sweep of disease-laden dust that wiped out whole cities, so is the screaming rocket that arcs and falls ten thousand miles away and kills a million people.

Although now there are no million people. A few hundred, more or less, living in the houses that the Dogs built for them because then the Dogs still knew what human beings were, still knew the connection that existed between them and looked on men as gods. Looked on men as gods and told the old tales before the fire of a winter evening and built against the day when Man might return and pat their heads and say, "Well done, thou good and faithful servant."

And that wasn't right, said Jenkins striding down the hill, that wasn't right at all. For men did not deserve that worship, did not deserve the godhood. Lord knows I loved them well enough, myself. Still love them, for that matter – but not because they are men, but because of the memory of a few of the many men.

It wasn't right that the Dogs should build for Man. For they were doing better than Man had ever done. So I wiped the memory out and a long, slow work it was. Over the long years I took away the legends and misted the memory and now they call men websters and think that's what they are.

I wondered if I had done right. I felt like a traitor and I spent bitter nights when the world was asleep and dark and I sat in the rocking chair and listened to the wind moaning in the eaves. For it was a thing I might not have the right to do. It was a thing the Websters might not have liked. For that was the hold they had on me, that they still have on me, that over the stretch of many thousand years I might do a thing and worry that they might not like it.

But now I know I'm right. The bow and arrow is the proof of that. Once I thought that Man might have got started on the wrong road, that somewhere in the dim, dark savagery that was his cradle and his toddling place, he might have got off on the wrong foot, might have taken the wrong turning. But I see that I was wrong. There's one road and one road alone that Man may travel – the bow and arrow road.

I tried hard enough, Lord knows I really tried.

When we rounded up the stragglers and brought them home to Webster House, I took away their weapons, not only from their hands but from their minds. I re-edited the literature that could be re-edited and I burned the rest. I taught them to read again and sing again and think again. And the books had no trace of war or weapons, no trace of hate or history, for history is hate – no battles or heroics, no trumpets."

But it was wasted time, Jenkins said to himself. I know now that it was wasted time. For a man will invent a bow and arrow, no matter what you do.

***

He had come down the long hill and crossed the creek that tumbled towards the river and now he was climbing again, climbing against the dark, hard uplift of the cliff-crowned hill.

There were tiny rustlings and his new body told his mind that it was mice, mice scurrying in the tunnels they had fashioned in the grass. And for a moment he caught the little happiness that went with the running, playful mice, the little, unformed, uncoagulated thoughts of happy mice.

A weasel crouched for a moment on the bole of a fallen tree and his mind was evil, evil with the thought of mice, evil with remembrance of the old days when weasels made a meal of mice. Blood hunger and fear, fear of what the Dogs might do if he killed a mouse, fear of the hundred eyes that watched against the killing that once had stalked the world.

But a man had killed. A weasel dare not kill, and a man had killed. Without intent, perhaps, without maliciousness. But he had killed. And the Canons said one must not take a life.

In the years gone by others had killed and they had been punished. And the man must be punished, too. But punishment was not enough. Punishment, alone, would not find the answer. The answer must deal not with one man alone, but with all men, with the entire race. For what one of them had done, the rest were apt to do. Not only apt to do, but bound to do – for they were men, and men had killed before and would kill again.

***

The Mutant castle reared black against the sky, so black that it shimmered in the moonlight. No light came from it, and that was not strange at all, for no light had come from it ever. Nor, so far as anyone could know, had the door ever opened into the outside world. The Mutants had built the castles, all over the world, and had gone into them and that had been the end. The Mutants had meddled in the affairs of men, had fought a sort of chuckling war with men and when the men were gone, the Mutants had gone, too.

Jenkins came to the foot of the broad stone steps that led up to the door and halted. Head thrown back, he stared at the building that reared its height above him.

I suppose Joe is dead, he told himself. Joe was long-lived, but he was not immortal. He would not live forever. And it will seem strange to meet another Mutant and know it isn't Joe.

He started the climb, going very slowly, every nerve alert, waiting for the first sign of chuckling humour that would descend upon him.

But nothing happened.

He climbed the steps and stood before the door and looked for something to let the Mutants know that he had arrived.

But there was no bell. No buzzer. No knocker. The door was plain, with a simple latch. And that was all.

Hesitantly, he lifted his fist and knocked and knocked again, then waited. There was no answer. The door was mute and motionless.

He knocked again, louder this time. Still there was no answer.

Slowly, cautiously, he put out a hand and seized the latch, pressed down with his thumb. The latch gave and the door swung open and Jenkins stepped inside.

***

"You're cracked in the brain," said Lupus. "I'd make them come and find me. I'd give them a run they would remember. I'd make it tough for them."

Peter shook his head. "Maybe that's the way you'd do it, Lupus, and maybe it would be right for you. But it would be wrong for me. Websters never run away."

"How do you know?" the wolf asked pitilessly. "You're just talking through your hair. No webster had to run away before and if no webster had to run away before, how do you know they never-"

"Oh, shut up," said Peter.

They travelled in silence up the rocky path, breasting the hill.

"There's something trailing us," said Lupus.

"You're just imagining," said. Peter. "What would be trailing us?"

"I don't know, but-"

"Do you smell anything?"

"Well, no."

"Did you hear anything or see anything?"

"No, I didn't, but-"

"Then nothing's following us," Peter declared, positively. "Nothing ever trails anything any more."

The moonlight filtered through the treetops, making the forest a mottled black and silver. From the river valley came the muffled sound of ducks in midnight argument. A soft breeze came blowing up the hillside, carrying with it a touch of river fog.

Peter's bowstring caught in a piece of brush and he stopped to untangle it. He dropped some of the arrows he was carrying and stooped to pick them up.

"You better figure out some other way to carry them things," Lupus growled at him. "You're all the time getting tangled up and dropping them and-"

"I've been thinking about it," Peter told him, quietly. "Maybe a bag of some sort to hang around my shoulder."

They went on up the hill.

"What are you going to do when you get to Webster House?" asked Lupus.

"I'm going to see Jenkins," Peter said. "I'm going to tell him what I've done."

"Fatso's already told him."

"But maybe he told him wrong. Maybe he didn't tell it right. Fatso was excited."

"Lame– brained, too," said Lupus.

They crossed a patch of moonlight and plunged on up the darkling path.

"I'm getting nervous," Lupus said. "I'm going to go back. This is a crazy thing you're doing. I've come part way with you, but-"

"Go back, then," said Peter bitterly. "I'm not nervous. I'm-"

He whirled around, hair rising on his scalp.

For there was something wrong – something in the air he breathed, something in his mind – an eerie, disturbing sense of danger and, much more than danger, a loathsome feeling that clawed at his shoulder blades and crawled along his back with a million prickly feet.

"Lupus!" he cried. "Lupus!"

***

A bush stirred violently down the trail and Peter was running, pounding down the trail. He ducked around a brush and skidded to a halt. His bow came up and with one motion be picked an arrow from his left hand, nocked it to the cord.

Lupus was stretched upon the ground, half in shade and half in moonlight. His lip was drawn back to show his fangs. One paw still faintly clawed.

Above him crouched a shape. A shape – and nothing else. A shape that spat and snarled a stream of angry sound that screamed in Peter's brain. A tree branch moved in the wind and the moon showed through and Peter saw the outline of the face – a faint outline, like the half erased chalk lines upon a dusty board. A skull-like face with mewling mouth and slitted eyes and ears that were tufted with tentacles.

The bow cord hummed and the arrow splashed into the face – splashed into it and passed through and fell upon the ground. And the face was there, still snarling.

Another arrow nocked against the cord and back, far back, almost to the ear. An arrow driven by the snapping strength of well-seasoned straight-grained hickory-by the hate and fear and loathing of the man who pulled the cord.

The arrow spat against the chalky outlines of the face, slowed and shivered, then fell free.

Another arrow and back with the cord. Farther yet, this time. Farther for more power to kill the thing that would not die when an arrow struck it. A thing that only slowed an arrow and made it shiver and then let it pass on through.

Back and back – and back. And then it happened. The bow string broke.

For an instant, Peter stood there with the useless weapon dangling in one hand, the useless arrow hanging from the other. Stood and stared across the little space that separated him from the shadow horror that crouched across the wolf's grey body.

And he knew no fear. No fear, even though the weapon was no more. But only flaming anger that shook him and a voice that hammered in his brain with one screaming word:

KILL-KILL-KILL

He threw away the bow and stepped forward, hands hooked at his side, hooked into puny claws.

The shadow backed away – backed away in a sudden pool of fear that lapped against its brain – fear and horror at the flaming hatred that beat at it from the thing that walked towards it. Hatred that seized and twisted it. Fear and horror it had known before – fear and horror and disquieting resignation – but this was something new. This was a whiplash of torture that seared across its nerves, that burned across its brain.

This was hatred.

The shadow whimpered to itself – whimpered and mewed and backed away and sought with frantic fingers of thought within its muddled brain for the symbols of escape.

***

The room was empty – empty and old and hollow. A room that caught up the sound of the creaking door and flung it into muffled distances, then hurled it back again. A room heavy with the dust of forgetfulness, filled with the brooding silence of aimless centuries.

Jenkins stood with the door pull in his hand, stood and flung all the sharp alertness of the new machinery that was his body into the corners and the darkened alcoves. There was nothing. Nothing but the silence and the dust and darkness. Nor anything to indicate that for many years there had been anything but silence, dust and darkness. No faintest tremor of a residuary thought, no footprints on the floor, no fingermarks scrawled across the table.